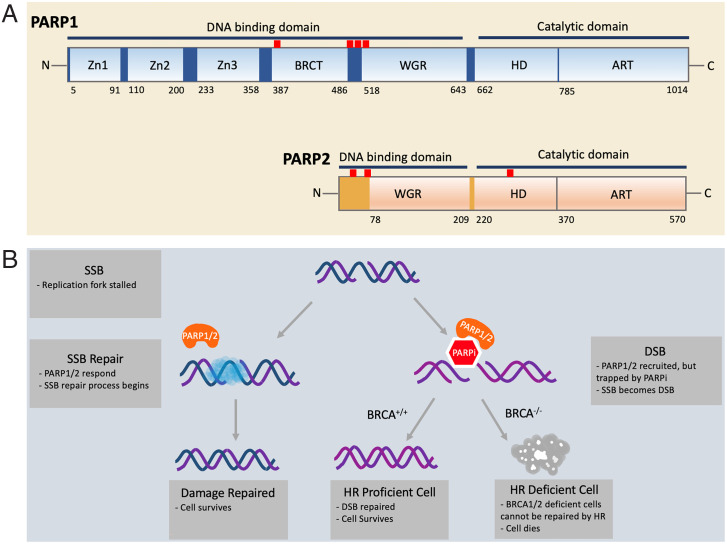

Fig. 1.

(A) Domain structure of PARP1 and PARP2. PARP1/2 contain DNA-binding domains and catalytic domains. In PARP1, the DNA-binding domain includes three zinc fingers (Zn1, Zn2, and Zn3), a breast cancer susceptibility protein-1 C terminus (BRCT) domain, and the tryptophan-glycine-arginine–rich (WGR) domain. The locations of the predominant automodification sites of PARP1 (D387, E488, E491, S499, S507, and S519) are indicated by red uptick bars. In PARP2, the DNA-binding domain includes an unstructured N-terminal region and the WGR domain. The catalytic domains of both PARP1/2 are composed of an alpha-helical subdomain (HD) and the ADP ribosyltransferase subdomain (CAT). The locations of the three known automodification sites of PARP2 (S47, S76, and S281) are indicated by red uptick bars. (B) The mechanism of synthetic BRCA1/2 deficiency and PARPi. During DNA replication, single-strand DNA is vulnerable to breakage. When a single-strand break (SSB) occurs, the replication fork is stalled. PARP1/2 (orange) arrive at the site of the damage and recruit other repair factors (blue cloud). In the presence of PARP1/2 inhibitor (red hexagon), however, PARP1/2 are trapped at the damage site, inhibiting the restart of replication. As a result of unresolved replication stress, a double-strand break (DSB) can arise. Homologous recombination (HR) is one of the most faithful ways to repair a DSB. Cells with functioning BRCA1/2 can carry out HR and restore the genomic integrity, but cancer cells with defective BRCA1/2 cannot. Thus, synthetic lethality selectively kills HR-deficient cancer cells in conjunction with a PARPi.