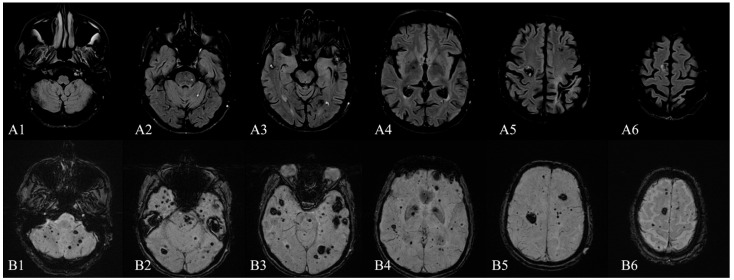

Figure 1.

Brain MRI (1.5 T)—December 2015: (A1–A6) axial FLAIR sequence and (B1–B6) axial SWI sequence (TE 40.00 ms) showing multiple infra- and supratentorial, bilateral, cavernous malformations (lesions in the order of tens), without recent signs of bleeding. The characteristic MRI appearance of CCMs consists of well-circumscribed “popcorn-like” lesions of different sizes with a mixed-signal intensity core and a hypointense peripheral rim of hemosiderin conferring a “blooming” effect [1,2,3]. This heterogeneous appearance is due to the presence of blood products in various stages of degradation [4]. Cavernous malformations are present in 0.3–0.5% of the general population, although some postmortem studies suggest that this number could be higher, up to 4% [1,5]. In most cases, they occur in sporadic forms (80%), usually with solitary lesions, but familial cases have also been reported. Familial cases usually present with multiple, congenital, and acquired lesions, in various locations: cerebral, spinal, retinal, and cutaneous [6,7,8]. Topographically, the majority of CNS cavernous malformations have a supratentorial localization (76%), followed by infra-tentorial regions (19%), the spinal involvement being seldomly encountered (5%) [9]. Furthermore, concomitant lesions at all of the three levels are exceptionally rare and they are a particularity of the familial forms of cavernous malformations [10,11]. Clinically, the majority of cerebral cavernous malformations (CCMs) become symptomatic between the second to fifth decades with findings such as seizures (23–50% of cases), headaches (6–52%), focal neurological deficits (20–45%) or hemorrhages (9–56%) [2,9,12]. Up to 40% of patients with such malformations are asymptomatic [12]. Imaging-wise, T2-weighted, gradient-echo MR (T2-GRE), high-field MR and especially susceptibility-weighted (SWI) MR sequences are the most sensitive techniques for detecting CCMs [1,13]. Here, we present the case of a 65-year-old man diagnosed in 2015 in our clinic with multiple supra- and infratentorial CCMs (Figure 1), whom we were following for secondary epilepsy with rare seizures with focal onset, impaired awareness, and secondary generalization. He used to take carbamazepine, but he had discontinued the treatment for the last three years despite our recommendations. More recently, he had been receiving a direct-acting oral anticoagulant indicated by the cardiologist as primary prophylaxis of cardioembolic stroke from atrial fibrillation with a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 2. Recently, in 2021, the patient was re-admitted into our clinic, this time for postural instability and motor deficit with gait impairment, with the onset three days prior. The initial neurologic examination showed temporo-spatial disorientation, hypophonia, right-side central facial paresis, asymmetric tetraparesis (force grading on the MRC scale of 4/5 in the upper limbs and 3/5 in the lower limbs), with the right side slightly more affected, upper limbs dysmetria, brisk deep tendon reflexes with Babinski sign, abnormal ataxic gait, which was possible for only a few steps with bilateral support. We also noted a significant cognitive decline from MMSE of 23 points in 2015 (mainly due to attention, orientation, and executive functions deficits) to severe dementia with a MMSE of 8 points in 2021, when the patient presented significantly slowed behavioral reaction time with failure to initiate Trail Making Test part B, reasoning difficulties and forgetfulness.