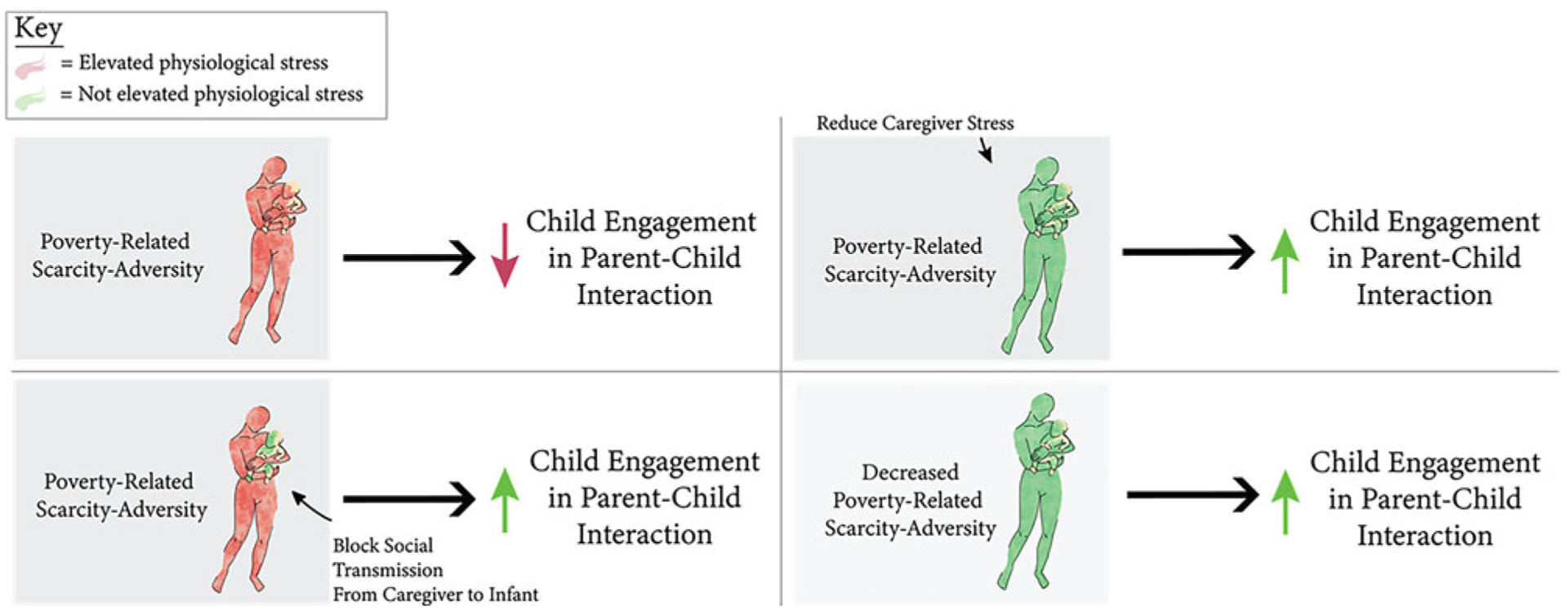

Figure 8.

Summary schematic of the current study’s findings and their implications for future research and interventional efforts. The present study’s findings provide novel, mechanistic support that poverty-related scarcity-adversity “gets under the skin” to raise infant physiological stress levels and disrupt child behavioral development by way of elevated caregiver physiological stress levels (top left). Blocking physiological social transmission from the primary caregiver to the infant might serve as one way to prevent negative impacts of environmental risk on child development (bottom left); however, future research is needed to determine the appropriateness and/or means by which to achieve this in real-world settings. Targeting upstream mechanisms of child outcomes via reduction of primary caregiver physiological stress (top right) and/or reduction of poverty-related scarcity-adversity exposure (bottom right) are additional, more readily translatable means by which to prevent or reduce the negative impacts of environmental risk on child behavioral development.