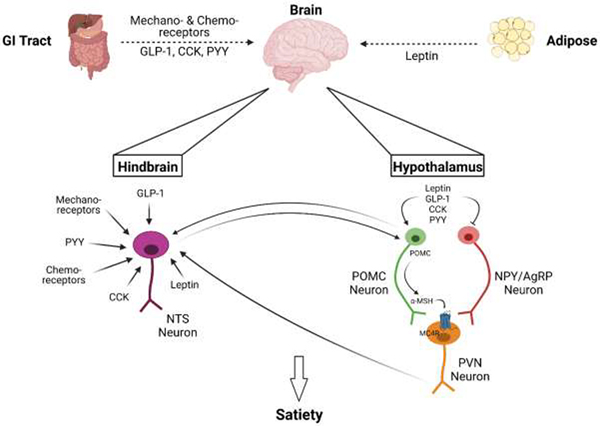

Figure 1. Broad Overview of Satiety Signaling.

The brain incorporates signals from multiple organs, primarily the gut and adipose, to determine appetite (dashed arrow). The gut communicates fullness via mechanoreceptors, chemoreceptors, and hormones including glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), cholecystokinin (CCK), and peptide YY (PYY). The adipokine leptin is also secreted from white adipose tissue to instigate anorexigenic signals. These signals are integrated in the hypothalamus and the hindbrain. In the hindbrain, neurons of the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS) receive these signals and can then communicate with neurons in the hypothalamus (solid arrows). In the hypothalamus, there are primarily two neuronal populations: anorexigenic pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC) neurons and orexigenic neuropeptide Y/Agouti-related peptide (NPY/AgRP) neurons. Anorexigenic peptides inhibit NPY/AgRP neurons and stimulate POMC neurons, which then synthesize POMC to be subsequently cleaved to α-melanocyte-stimulating hormone (α-MSH), which then primarily binds to melanocortin-4 receptor (MC4R) of the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) neurons, which then releases downstream signals, including to the NTS, to induce satiety and restrict eating. Created with BioRender.com.