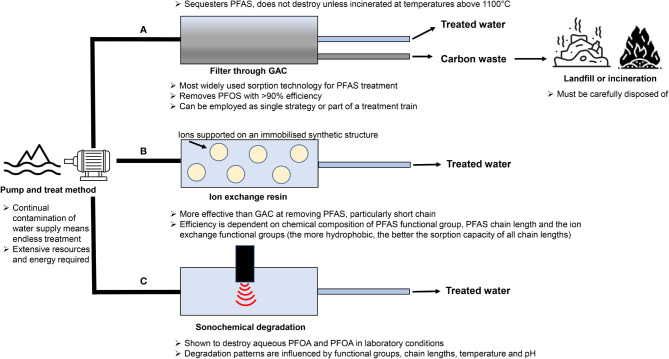

Figure 4.

Schematic diagram of three possible treatment mechanisms for PFAS contaminated water. (A) Carbon-rich sorbents such as granular activated carbon (GAC) have a long history of being utilised to remove a variety of organic contaminants from water and as such are by far the best studied and most widely used sorption technology for treating PFAS contaminated water sources (208). Granular activated carbon has been shown to reliably remove PFOS with over 90% efficiency (59, 210) and is thus now the reference point for comparison of all new PFAS water sorption technologies. This technology can be employed to treat water before it reaches consumers, either as a single strategy, or as part of an integrated treatment programme. This treatment often involves the pump and treat method in which groundwater is extracted and filtered (208, 211), with the sorbent then being disposed of in landfill sites, provided certain risk criteria are met and the chemicals remain sequestered. International conventions state that waste materials containing > 50 mg/kg of PFAS must be treated in such a way as to destroy these chemicals, which is often accomplished by incinerating at high temperatures (over 1100°C) (208, 212). (B) Ion exchange uses anion exchange to target a wider range of PFAS, allowing for more efficient removal. Removal occurs via electrostatic interactions between the charged functional groups of PFAS chemicals and ions supported on an immobilized synthetic structure (213). In comparison to activated carbon treatment, this method has been shown to be more effective in removing PFAS, particularly the short chain variants (205). However, the efficiency of ion exchange technologies is dependent on several factors, such as the chemical composition of PFAS functional group, PFAS chain length and the ion exchange functional groups (the more hydrophobic, the better the sorption capacity of all chain lengths) (213). The success of almost all remediation strategies employed has been shown to depend on the perfluoroalkyl chain length, with increased efficacy seen with smaller chain length (214). (C) However, simply removing PFAS from water does not destroy the chemical, hence why further processing or incineration is required, making removal techniques lengthy and potentially hazardous. Sonochemical degradation has been shown to destroy aqueous PFOA and PFOA in laboratory conditions (213), demonstrating sonic irradiation can be effectively employed to reduce PFAS contamination at environmentally relevant levels (215). The degradation patterns of PFAS chemicals are influenced by their functional groups and chain lengths as well as physical variables such as temperature and pH (216). Utilizing the method of groundwater pumping is seen as a potentially endless endeavor due to continual contamination from untreated water sources. This, in turn, raises questions as to whether the pump and treat method is sustainable in the long-term treatment of PFAS contamination due to extensive resources and energy required (208).