Abstract

Neuroimaging studies have revealed hippocampal hyperactivity in schizophrenia. In the early stage of the illness, hyperactivity is present in the anterior hippocampus and is thought to spread to other regions as the illness progresses. However, there is limited evidence for changes in basal hippocampal function following the onset of psychosis. Resting state functional MRI signal amplitude may be a proxy measure for increased metabolism and disrupted oscillatory activity, both consequences of an excitation/inhibition imbalance underlying hippocampal hyperactivity. Here, we used fractional amplitude of low frequency fluctuations (fALFF) to test the hypothesis of progressive hippocampal hyperactivity in a two-year longitudinal case-control study. We found higher fALFF in the anterior and posterior hippocampus of individuals in the early stage of non-affective psychosis at study entry. Contrary to our hypothesis of progressive hippocampal dysfunction, we found evidence for normalization of fALFF over time in psychosis. Our findings support a model in which hippocampal fALFF is a marker of psychosis vulnerability or acute illness state rather than an enduring feature of the illness.

Keywords: schizophrenia, hippocampus, ALFF, excitation/inhibition imbalance, longitudinal

1. Introduction

Hippocampal hyperactivity has been proposed as a core pathophysiological mechanism for psychosis (Lieberman et al., 2018) and a treatment target for schizophrenia (Tregellas, 2014). This hyperactivity is thought to result from an E/I imbalance due to a deficit of parvalbumin positive (PV+) interneurons or NMDA receptor hypofunction (Lisman et al., 2008). The strongest evidence for hippocampal hyperactivity in psychosis comes from imaging studies of underlying metabolism such as cerebral blood volume (CBV) mapping (Schobel et al., 2013; Talati et al., 2015). However, this type of imaging requires the use of a contrast agent (Small et al., 2011) and can be challenging to use in the assessment of patients with a psychotic disorder (McHugo et al., 2019). Alternative methods that can be used for longitudinal measurement of hippocampal function in patients are needed.

An E/I imbalance in psychosis leading to hyperactivity should be detectable with the amplitude of resting state fMRI fluctuations. Aberrant signaling in PV+ interneurons disrupts oscillatory activity in the hippocampus (Bartos et al., 2007). The impact of PV+ interneuron dysfunction on oscillatory activity is most pronounced in the gamma frequency range (Mathalon et al., 2015). The resting state fMRI signal amplitude is associated with gamma range oscillations (Niessing et al., 2005; Scholvinck et al., 2010) and underlying glucose metabolism (Aiello et al., 2015; Tomasi et al., 2013). The spatial distribution of PV+ interneurons and variation in PV+ interneuron-related genes have been linked to resting state fMRI amplitude and risk for psychosis (Anderson et al., 2020). Cross-sectional studies have found increased amplitude of low frequency fluctuations in the hippocampus in individuals at high-risk for psychosis (Tang et al., 2015), early psychosis (Tang et al., 2019), and chronic schizophrenia (Hare et al., 2018, 2017; Hoptman et al., 2010; McHugo et al., 2015; Turner et al., 2013), validating the idea that hippocampal hyperactivity can be identified with resting state fMRI fluctuation amplitude.

Spreading of hippocampal hyperactivity from the anterior region has been proposed as a marker of illness progression (Lieberman et al., 2018). Preclinical models and neuroimaging studies indicate that the anterior hippocampus is affected early in psychotic illness (Lodge and Grace, 2011; McHugo et al., 2019; Provenzano et al., 2020; Schobel et al., 2013). Previous CBV studies of the relationship between hippocampal hyperactivity and psychosis progression have examined the transition from the prodromal or high-risk state to frank psychosis (Provenzano et al., 2020; Schobel et al., 2013, 2009) but have not considered longitudinal changes following the onset of a psychotic illness. Additionally, these analyses have been based on stratification of a cross-sectional imaging dataset based on longitudinal clinical outcomes rather than longitudinal assessment of hippocampal function within individuals. To our knowledge, there has been only a single longitudinal study of fMRI low frequency fluctuations in psychosis (Li et al., 2016), but results in the hippocampus were not reported. Past studies of hippocampal low frequency fluctuations in psychosis have not tested for differences in anterior and posterior regions of the hippocampus (Hare et al., 2018, 2017; McHugo et al., 2015). Thus, it is unclear whether there is progressive basal hippocampal dysfunction following psychosis onset and whether anterior and posterior hippocampal regions are differentially affected.

Here, we measured the fractional amplitude of low frequency fluctuations (fALFF) in a longitudinal study design to test the hypothesis of a progressive hippocampal E/I imbalance in the early stage of psychosis. We used fractional ALFF because it is less susceptible than standard ALFF to motion and physiological artifacts (Yan et al., 2013; Zou et al., 2008). We tested two hypotheses: first, we tested whether anterior (but not posterior) hippocampal fALFF is higher in early psychosis individuals than in healthy controls at study entry; and second, whether anterior hippocampal fALFF progresses (i.e., increases further and spreads to posterior regions) over two years in the early stage of psychosis. Finally, we conducted a secondary analysis to explore whether higher fALFF is common to all early psychosis individuals regardless of illness progression or is increased only in individuals with persistent psychosis leading to a schizophrenia diagnosis after two years.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Participants

Participants (N=137) were 68 individuals in the early stage of a non-affective psychotic disorder and 69 demographically similar healthy control individuals recruited between May 2013 and February 2018 for a prospective two-year longitudinal study (Table 1). Early psychosis participants were recruited from the inpatient and outpatient clinics of the Vanderbilt University Medical Center Psychiatric Hospital and healthy controls were recruited from the surrounding community through advertisements. Groups were recruited to be matched for mean age, gender, race, and parental education. Data from participants in this cohort have been included in previous reports (Armstrong et al., 2018; Avery et al., 2021, 2019b, 2019a; McHugo et al., 2021, 2020, 2019, 2018) but the longitudinal fMRI data and analyses presented here have not been reported previously. None of the participants in the current study were included in our previous report on ALFF/fALFF in schizophrenia (McHugo et al., 2015). All participants provided written informed consent and received monetary compensation for their time. The Vanderbilt University Institutional Review Board approved the study.

Table 1.

Participant demographic, cognitive, and clinical characteristics at study entry.

|

Healthy Control

N=67 |

Early Psychosis

N=59 |

Healthy Control >

Early Psychosis |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Statistic | df | p | |

|

| |||||||

| Age (years) | 21.82 | 2.84 | 21.36 | 3.93 | t=0.75 | 104 | 0.45 |

| Parental education (years)a | 15.02 | 2.38 | 15.60 | 2.80 | t=−1.23 | 113 | 0.22 |

| WTAR | 112.10 | 10.73 | 104.75 | 14.91 | t=3.05 | 101 | 0.003 |

| SCIP Total Z | 0.25 | 0.58 | −0.82 | 0.83 | t=8.31 | 102 | <0.001 |

| Framewise displacement | 0.18 | 0.04 | 0.16 | 0.05 | t=1.49 | 108 | 0.14 |

| PANSS | |||||||

| Positive | 17.22 | 7.01 | |||||

| Negative | 17.66 | 7.71 | |||||

| General | 32.71 | 9.15 | |||||

| Duration of psychosis (months) | 6.19 | 5.52 | |||||

| Duration of untreated psychosis (months)c | 2.21 | 4.22 | |||||

| CPZ equivalents | 323.30 | 153.79 | |||||

|

| |||||||

| N | N | Statistic | df | p | |||

|

| |||||||

| Gender (Male/Female) | 50/17 | 46/13 | X2=0.19 | 1 | 0.66 | ||

| Race (White/Black/Other) | 53/10/4 | 45/13/1 | X2=2.35 | 2 | 0.31 | ||

| Smokers/Non-smokers | 1/66 | 16/43 | X2=15.52 | 1 | <0.001 | ||

| Number medicated with APD | 52 | ||||||

| Diagnosis | |||||||

| Schizophreniform disorder | 40 | ||||||

| Schizophrenia | 18 | ||||||

| Schizoaffective disorder | 1 | ||||||

Abbreviations: WTAR: Wechsler Test of Adult Reading; SCIP: Screen for Cognitive Impairment in Psychiatry; PANSS: Positive and Negative Symptom Scale; CPZ: Chlorpromazine; APD: Anti-psychotic Drugs.

Parental education was unavailable for one EP participant.

WTAR was unavailable for six HC participants and two EP participants.

Duration of untreated psychosis was unavailable for four EP participants.

Inclusion criteria for patients were a non-affective psychotic disorder diagnosis with a duration of psychosis less than 2 years. Exclusion criteria for all participants included the presence of significant head injury, major medical illnesses, pregnancy, metal, claustrophobia, and current substance abuse or dependence within the past month at the time of study enrollment. Two participants were excluded because of ineligible diagnoses at follow-up (HC=1, EP=1). Data on participant attrition is presented in Figure S1 in the supplementary materials. Early psychosis participants who completed the study did not differ from those who were lost to follow-up on demographic or clinical characteristics.

2.2. Clinical and cognitive characterization

Clinical and cognitive data were collected during in-person interviews at study entry and after two years. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV, TR (SCID) (First et al., 2002) was used to assess psychiatric diagnoses. All data gathered during the in-person interviews were augmented by extensive review of all available medical records. Diagnostic consensus meetings were held and final diagnoses were made by psychiatrist SH. Clinical symptoms at the time of scanning were described using the Positive and Negative Symptom Scale (PANSS (Kay et al., 1987)). The Symptom Onset in Schizophrenia Inventory (SOS (Perkins et al., 2000)) was used to identify the onset of psychosis. The duration of psychosis was calculated as the amount of time between the date of onset of psychosis (determined with the SOS) and study enrollment. The duration of untreated psychosis was calculated as the time between the date of onset of psychosis (determined with the SOS) and the date of first antipsychotic treatment. Chlorpromazine equivalents were calculated using established formulas (Gardner et al., 2010; Leucht et al., 2014). The Wechsler Test of Adult Reading (WTAR (Wechsler, 2001)) was used to estimate premorbid IQ. Cognitive function was assessed at study entry and two-year follow-up using the Screen for Cognitive Impairment in Psychiatry (SCIP (Purdon, 2005)). Demographic, clinical, and cognitive characteristics of the sample at study entry are described in Table 1. Characteristics of the participants who were eligible for longitudinal follow-up are presented in Table S1 in the supplement.

2.3. MRI data acquisition and preprocessing

Imaging data were collected at study entry and after two years (median time to follow-up in months: 24, interquartile range: 23–24). We acquired a 3D T1-weighted image on one of two identical 3T Philips Intera Achieva scanners with a 32-channel head coil (Philips Healthcare, Inc., Best, The Netherlands) at the Vanderbilt University Institute of Imaging Science (voxel size = 1mm3; field of view = 256mm2; number of slices = 170; gap = 0mm; TE = 3.7ms; TR = 8.0ms). We found no effect of scanner on fALFF in our primary analyses (p’s > 0.76) and have reported models without this covariate to minimize the number of model parameters being tested. Each structural image was visually inspected for motion or other artifacts prior to inclusion. Whole brain resting state functional images were acquired with an echo planar imaging sequence (38 ascending slices, oriented at −15° relative to the intercommissural plane; voxel size = 3.0 × 3.0 × 3.2mm; TR = 2s; TE = 28.0ms; flip angle = 90°; 203 volumes). Participants were instructed to remain still with their eyes closed during the scan. Immediately following the end of the scan, participants were asked if they remained awake and data were excluded if they reported falling asleep at any point during the scan.

Structural data were preprocessed using CAT12 (http://www.neuro.uni-jena.de/cat) and functional data were preprocessed in SPM12 (http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm) and denoised using custom Matlab code (https://github.com/baxpr/connprep). The T1 structural image was segmented into grey matter, white matter, and CSF and normalized to MNI space using default parameters with CAT12. Functional images were realigned to the mean image using SPM12. The mean image was then coregistered to the native-space T1 image using rigid-body alignment. The realigned functional images were normalized by applying the deformation fields derived from CAT12 preprocessing of the structural image. Normalized functional images underwent denoising by simultaneous regression-based removal of 6 translation and rotation motion parameters obtained from realignment and their first differences as well as 6 principal components derived from the white matter and CSF. Framewise displacement was calculated for each participant using the method described in (Power et al., 2012). Participants were excluded if their median framewise displacement exceeded 1.5 times the interquartile range of the sample (FD > 0.27).

Anterior and posterior hippocampal regions of interest (ROIs) were obtained by multi-atlas segmentation of the native space T1 structural image (Plassard et al., 2021). Automated segmentations were obtained by multi-atlas label fusion based on in-house manual segmentations of the hippocampus on 195 individuals, including 105 persons with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. The anterior and posterior regions of the hippocampus were divided by an anatomical landmark, the uncus (Woolard and Heckers, 2012). The final slice of the anterior region was defined as the last coronal slice in which there are two cuts visible through the hippocampus. Hippocampal segmentations were visually inspected for errors. Segmentations that included tissue outside the hippocampus or had portions of the hippocampus cut off were excluded from further analysis. The ROIs were normalized to MNI space using the CAT12 deformation fields with nearest neighbor interpolation.

Details regarding participant attrition are included in Supplementary Figure S1. Data from 9 participants were excluded at study entry for data quality issues (asleep during fMRI, N=2; motion on the structural image, N=3; artifact on fMRI, N=1; median framewise displacement (FD) during fMRI > 0.27, N=3). Two participants were excluded for ineligible diagnoses at follow-up. Study entry MRI scans that passed quality control were available on 59 early psychosis and 67 control participants. Sixteen participants were lost to follow-up. Follow-up data from eight participants at follow-up were excluded for ineligibility (metal, N=1) or data quality issues (asleep during fMRI, N=1; median framewise displacement (FD) during fMRI > 0.27, N=3; data quality, N=2; technical issues, N=1). Complete two-year follow-up data that passed quality control were available on 51 early psychosis (86%) and 51 healthy control (76%) individuals.

2.4. fALFF analysis

As in our previous work (McHugo et al., 2015), the fractional amplitude of low frequency fluctuations (fALFF) was calculated using AFNI’s 3dRSFC tool (Taylor and Saad, 2013). Linear and quadratic trends were removed from the preprocessed and denoised fMRI time-series, which was then converted to a power spectrum using a Fourier transform. fALFF was calculated as the average of the power in the range 0.01 – 0.1 Hz relative to the entire frequency spectrum. fALFF for each voxel was then normalized by dividing the mean fALFF within the whole brain. Average normalized fALFF values were extracted from the anterior and posterior hippocampal ROIs separately in each hemisphere and entered into statistical analyses as described below.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis of fALFF was carried out using linear mixed models in R (R Core Team, 2019) with the packages lmerTest (Kuznetsova et al., 2017), emmeans (Lenth, 2018), and car (Fox and Weisberg, 2011). Reported effect sizes were calculated using the robust effect size index, S (Vandekar et al., 2020). We tested our primary hypotheses by fitting a model with fALFF as the outcome variable, group (healthy control, early psychosis), hemisphere (left, right), region (anterior, posterior), time (t0=study entry, t2yr=two-year follow-up), and their interaction as fixed effects, and participant as a random effect. In a secondary analysis, we examined the relationship between illness progression and fALFF by stratifying patients based on their two-year follow-up diagnosis (schizophreniform disorder vs. schizophrenia). We conducted significance tests on the fixed effects using analysis of variance (ANOVA) on the model output. Significant effects were followed up with contrasts adjusted for multiple comparisons using Bonferroni correction.

Hippocampal hyperactivity has been previously linked to psychosis symptoms (Tregellas, 2014). In order to examine whether hippocampal fALFF was associated with clinical features or medication effects, we carried out exploratory analyses using robust linear regression with the R package MASS (Venables and Ripley, 2013) using continuous measures of PANSS scores, duration of psychosis, and medication load (CPZ equivalents). We chose to use mean total hippocampal fALFF for these analyses because we did not find evidence in our primary model for region-specific differences in fALFF. Median framewise displacement was included as a covariate in all models to adjust for differences in motion.

3. Results

3.1. Group differences in fALFF

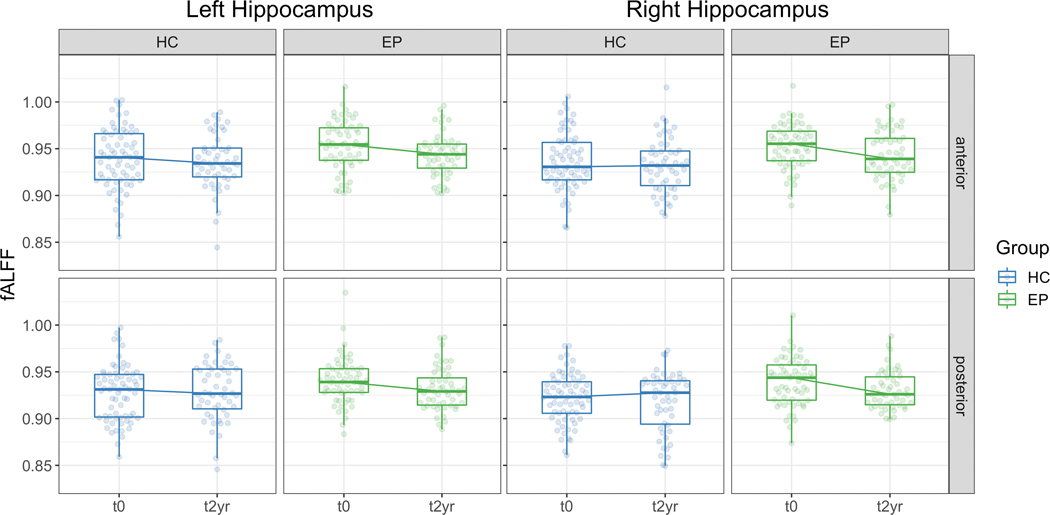

Hippocampal fALFF was higher in early psychosis participants compared to healthy controls (main effect of Group (F1,125=8.95, p=0.003, S=0.25). Contrary to our hypotheses, we did not find evidence that the anterior region was more affected than the posterior region (Group X Region interaction: F1,772=0.12, p=0.73, S=0); Group X Region X Hemisphere interaction: F1,772=0.61, p=0.43, S=0). fALFF is greater at study entry (t0) in early psychosis but we did not observe evidence that the early psychosis group differed from healthy controls at two-year follow-up (t2yr, Figure 1; Group X Visit interaction: F1,809=7.73, p=0.006, S=0.09; t0: t161=3.96, p<0.001, S=0.30; t2yr: t189=1.60, p=0.23, S=0.09).

Figure 1.

fALFF is increased in the hippocampus in early psychosis individuals at study entry (t0) but not after two years (t2yr). Boxplots show the median and interquartile range of unadjusted fALFF.

In a secondary analysis, we examined whether hippocampal fALFF differed by illness progression in early psychosis participants. fALFF was higher at study entry in early psychosis participants regardless of subsequent diagnosis, but was similar to healthy controls after two years (Figure 2; Group X Visit interaction: F2,732=5.32, p=0.005, S=0.07; t0: SZF>HC, t150=2.79, p=0.02, S=0.21; SZ>HC, t147=4.26, p<0.001, S=0.34; t2yr: SZF>HC, t155=1.95, p=0.21, S=0.13; SZ>HC, t157=1.54, p=0.50, S=0.09).

Figure 2.

Hippocampal fALFF is increased at study entry (t0) in early psychosis individuals regardless of subsequent illness progression but does not differ from healthy controls after 2 years (t2yr). Boxplots show the median and interquartile range of unadjusted fALFF.

3.2. Association of fALFF and clinical factors in early psychosis

In a series of exploratory analyses, we examined whether mean total hippocampal fALFF was associated with clinical features in the early psychosis group. At study entry, we found a trend level association of fALFF with positive (F1,56=3.18, p=0.08, S=0.20) and general (F1,56=3.64, p=0.06, S=0.22) symptoms but not negative symptoms (negative: F1,56=0.42, p=0.52, S=0) as measured by the PANSS. Changes in fALFF over two years were not associated with changes in psychosis symptoms (positive: F1,47=2.90, p=0.10, S=0.20; negative: F1,47=0.44, p=0.51, S=0; general: F1,47=1.40, p=0.24, S=0.09). fALFF was not related to duration of psychosis (F1,56=0.48, p=0.49, S=0), antipsychotic dosage (chlorpromazine equivalents; F1,49=0.01, p=0.94, S=0), or smoking status (F1,56=1.02, p=0.32) at study entry.

4. Discussion

Current pathophysiological models indicate that hippocampal hyperactivity plays a key role in psychosis (Heckers and Konradi, 2014; Tamminga et al., 2012), with early dysfunction in the anterior hippocampus spreading to the posterior region as the illness progresses (Lieberman et al., 2018). Here, we found higher fALFF at study entry across both anterior and posterior regions of the hippocampus in individuals in the early stage of psychosis. However, we observed evidence of fALFF normalization in the early psychosis group over two years regardless of illness progression, rather than worsening.

The present data suggest that hippocampal hyperactivity may be a marker of acute psychosis. We found greater hippocampal fALFF in the early psychosis group only at study entry, not at two-year follow-up. Early psychosis patients were enrolled in the study during the initial months following illness onset (mean duration of psychosis = 6.19 months). PANSS scores at study entry indicate that many were experiencing moderate symptoms at the time of the initial scan. In contrast, patients were less symptomatic at two-year follow-up (Table S1). We found a modest association between hippocampal fALFF and positive and general psychosis symptoms at study entry. This pattern of results suggests the possibility that increased activity is associated with greater acute illness burden. These findings fit with longitudinal data in high-risk individuals showing that a decrease in hippocampal perfusion over time is associated with a concomitant reduction in psychotic symptoms (Allen et al., 2016). Additionally, one previous study found that low frequency fluctuations within the left hippocampus were greatest in individuals who experienced visual and auditory hallucinations compared to those reporting only auditory hallucinations (Hare et al., 2017). Broadly, our data are consistent with both neuroimaging studies of hippocampal hyperactivity in patients (reviewed in (Tregellas, 2014)) and mechanistic studies linking excitation/inhibition imbalance within the hippocampus to psychosis symptoms (Bryant et al., 2019). The pathway from hippocampal hyperactivity to psychosis is likely multifarious and mediated by the direct consequences of hippocampal dysfunction on cognition (Heckers, 2001). Future large-scale studies that combine deep clinical phenotyping, multiple measures of hippocampal-dependent cognition, and functional imaging of hippocampal activity are needed to better elucidate the mechanisms by which hyperactivity may lead to the experience of psychosis.

Our findings support recent proposals that hippocampal hyperactivity confers vulnerability to psychosis. In the current study, we found greater hippocampal fALFF at study entry in both individuals who had a two-year follow-up diagnosis of schizophrenia and those whose psychosis remitted (i.e., they maintained a diagnosis of schizophreniform disorder). This suggests that fALFF is not predictive of illness progression following psychosis onset. Increased hippocampal function in individuals at high-risk for psychosis has been found with multiple methods (CBV and cerebral blood flow; (Allen et al., 2016; Schobel et al., 2009)) and has been replicated in large cohorts (Allen et al., 2018; Provenzano et al., 2020). In contrast to an earlier report (Schobel et al., 2013), a recent replication study did not find evidence that higher hippocampal CBV in high-risk individuals was associated with progression to a psychotic disorder (Provenzano et al., 2020). Higher hippocampal ALFF is present in both early-stage schizophrenia and those at genetic high-risk for schizophrenia relative to healthy individuals (Tang et al., 2019). Collectively, these findings suggest that hippocampal hyperactivity may be a psychosis vulnerability factor rather than a core feature of schizophrenia. If this hypothesis is correct, treatments that decrease hippocampal excitability or activity may also reduce risk for developing psychosis or its recurrence (Gomes et al., 2016; Koh et al., 2018; Perez and Lodge, 2014).

Our results add to a growing body of literature showing greater hippocampal low frequency fluctuations in chronic (Hare et al., 2017; Hoptman et al., 2010; McHugo et al., 2015; Turner et al., 2013) and early schizophrenia (Tang et al., 2019). We did not confirm the hypothesis of selectively increased fALFF in the anterior hippocampus in early psychosis, but instead found evidence for greater fALFF across anterior and posterior regions. This finding dovetails with a task-related fMRI study of scene memory that found evidence for dysfunction in both the anterior and posterior hippocampus in early-stage schizophrenia (Ragland et al., 2017). Most previous reports of a selective increase in basal activity in the anterior hippocampus have come from studies that used CBV mapping (McHugo et al., 2019; Provenzano et al., 2020; Schobel et al., 2009; Talati et al., 2014). The measure used in the present study, fALFF, is dependent on fluctuations in the blood oxygen level dependent (BOLD) signal and does not provide a quantitative measure of underlying physiology or metabolism. While low frequency fluctuations of the BOLD signal are correlated with glucose metabolism (Aiello et al., 2015; Tomasi et al., 2013), the BOLD signal itself may be more susceptible than CBV to transient changes in brain function or acute illness (Small et al., 2011). This would fit with our observation that between-group differences in fALFF were limited at two-year follow-up when early psychosis individuals were less ill: PANSS scores at study entry were higher on average compared to follow-up (positive: 16.41 vs. 12.76; negative: 17.35 vs. 11.82; general: 31.55 vs. 25.96; details for complete follow-up data provided in Table S1). Future studies employing techniques such as calibrated fMRI (Blockley et al., 2013) or multimodal neuroimaging (Uludağ and Roebroeck, 2014) are needed to determine how individual differences in metabolism and/or hemodynamic responses relate to the clinical manifestations of psychosis.

The primary strength of our study is the longitudinal assessment of fALFF in the early stage of psychosis. The study had several limitations. Our early psychosis cohort only included individuals with a non-affective psychotic disorder diagnosis. Additional work is needed to explore whether hippocampal hyperactivity is present across affective and non-affective psychoses to confirm the generalizability of these findings across the psychosis spectrum. Additionally, we examined fALFF differences in subgroups of early psychosis based on their two-year follow-up diagnosis (schizophrenia vs. schizophreniform disorder), but the small sample size for the schizophreniform disorder group at follow-up is a limitation. Larger longitudinal studies are needed to determine whether there are subgroup-specific differences in hippocampal fALFF. Additionally, most individuals with early psychosis in our study were medicated. Even though we did not find an association between fALFF and chlorpromazine equivalents, we cannot rule out the possibility that our results were affected by antipsychotic medications. However, the presence of higher hippocampal low frequency fluctuations in groups at risk for psychosis suggests that this possibility is not likely to have substantial impact (Tang et al., 2019). In contrast to previous studies (Wang et al., 2017; Xue et al., 2020), we did not observe differences in fALFF related to smoking. ALFF findings in the hippocampus were not reported in either study, so it is possible that smoking does not differentially impact LFFs in the hippocampus. An intriguing alternative that warrants future study is that nicotine use may impact hippocampal function in a manner that is detectable with the dynamic measures of ALFF used by Xue et al., rather than the static measure of fALFF reported in the current study. Finally, the gender distribution in our sample is not representative of the schizophrenia population. Future studies examining sex- and gender-specific differences in hippocampal function in a large early psychosis cohort are needed to confirm the present findings.

5. Conclusions

Our results suggest that hippocampal fALFF is higher in the early stage of psychosis and supports a model of hippocampal hyperactivity as a risk factor for psychosis. We did not find evidence that hippocampal fALFF is associated with illness progression, but rather that it may be related to acute illness state or psychosis vulnerability. Larger studies are needed to confirm this possibility. If higher hippocampal fALFF is associated with acute illness or psychosis vulnerability, future studies should explore whether it represents a viable target for therapies aimed at reducing hippocampal hyperactivity.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Charlotte and Donald Test Fund, NIMH grants R01-MH70560 (Heckers) and R01-MH123563 (Vandekar), the Vanderbilt Psychiatric Genotype/Phenotype Project, the Vanderbilt Institute for Clinical and Translational Research (through grant 1-UL-1-TR000445 from the National Center for Research Resources/NIH) and the Advanced Computing Center for Research and Education at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN. The authors would like to thank the participants for their involvement and Xinyu Liu, Rachel McKinney, Margo Menkes, Margaret Quinn, Caitlin Ridgewell, and Katherine Seldin for their assistance in data collection.

References

- Aiello M, Salvatore E, Cachia A, Pappatà S, Cavaliere C, Prinster A, Nicolai E, Salvatore M, Baron JC, Quarantelli M, 2015. Relationship between simultaneously acquired resting-state regional cerebral glucose metabolism and functional MRI: A PET/MR hybrid scanner study. Neuroimage 113, 111–121. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.03.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen P, Azis M, Modinos G, Bossong MG, Bonoldi I, Samson C, Quinn B, Kempton MJ, Howes OD, Stone JM, Calem M, Perez J, Bhattacharayya S, Broome MR, Grace AA, Zelaya F, McGuire P, 2018. Increased Resting Hippocampal and Basal Ganglia Perfusion in People at Ultra High Risk for Psychosis: Replication in a Second Cohort. Schizophr. Bull 44, 1323–1331. 10.1093/schbul/sbx169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen P, Chaddock CA, Egerton A, Howes OD, Bonoldi I, Zelaya F, Bhattacharyya S, Murray R, McGuire P, 2016. Resting hyperperfusion of the hippocampus, midbrain, and basal ganglia in people at high risk for psychosis. Am. J. Psychiatry 173, 392–399. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15040485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson KM, Collins MA, Chin R, Ge T, Rosenberg MD, Holmes AJ, 2020. Transcriptional and imaging-genetic association of cortical interneurons, brain function, and schizophrenia risk. Nat. Commun 2020 111 11, 1–15. 10.1038/s41467-020-16710-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong K, Avery S, Blackford JU, Woodward N, Heckers S, 2018. Impaired associative inference in the early stage of psychosis. Schizophr. Res 202, 86–90. 10.1016/j.schres.2018.06.049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avery SN, Armstrong K, Blackford JU, Woodward ND, Cohen N, Heckers S, 2019a. Impaired relational memory in the early stage of psychosis. Schizophr. Res 212, 113–120. 10.1016/j.schres.2019.07.060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avery SN, Armstrong K, McHugo M, Vandekar S, Blackford JU, Woodward ND, Heckers S, 2021. Relational Memory in the Early Stage of Psychosis: A 2-Year Follow-up Study. Schizophr. Bull 47, 75–86. 10.1093/SCHBUL/SBAA081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avery SN, McHugo M, Armstrong K, Blackford JU, Woodward ND, Heckers S, 2019b. Disrupted Habituation in the Early Stage of Psychosis. Biol. Psychiatry Cogn. Neurosci. Neuroimaging 4, 1004–1012. 10.1016/j.bpsc.2019.06.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartos M, Vida I, Jonas P, 2007. Synaptic mechanisms of synchronized gamma oscillations in inhibitory interneuron networks. Nat. Rev. Neurosci 8, 45–56. 10.1038/nrn2044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blockley NP, Griffeth VEM, Simon AB, Buxton RB, 2013. A review of calibrated blood oxygenation level-dependent (BOLD) methods for the measurement of task-induced changes in brain oxygen metabolism. NMR Biomed. 26, 987–1003. 10.1002/nbm.2847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant JE, Frölich M, Tran S, Reid MA, Lahti AC, Kraguljac NV, 2019. Ketamine induced changes in regional cerebral blood flow, interregional connectivity patterns, and glutamate metabolism. J. Psychiatr. Res 117, 108–115. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2019.07.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First M, Spitzer R, Miriam G, Williams J, 2002. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Patient Edition with Psychotic Screen (SCID-I/P W/PSY SCREEN). [Google Scholar]

- Fox J, Weisberg S, 2011. An R companion to applied regression, 2nd ed. SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner DM, Murphy AL, O’Donnell H, Centorrino F, Baldessarini RJ, 2010. International Consensus Study of Antipsychotic Dosing. Am. J. Psychiatry 167, 686–693. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09060802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes FV, Rincón-Cortés M, Grace AA, 2016. Adolescence as a period of vulnerability and intervention in schizophrenia: Insights from the MAM model. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.05.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hare SM, Ford JM, Ahmadi A, Damaraju E, Belger A, Bustillo J, Lee HJ, Mathalon DH, Mueller BA, Preda A, van Erp TGM, Potkin SG, Calhoun VD, Turner JA, 2017. Modality-Dependent Impact of Hallucinations on Low-Frequency Fluctuations in Schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull 43, 389–396. 10.1093/schbul/sbw093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hare SM, Law AS, Ford JM, Mathalon DH, Ahmadi A, Damaraju E, Bustillo J, Belger A, Lee HJ, Mueller BA, Lim KO, Brown GG, Preda A, van Erp TGM, Potkin SG, Calhoun VD, Turner JA, 2018. Disrupted network cross talk, hippocampal dysfunction and hallucinations in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res 199, 226–234. 10.1016/J.SCHRES.2018.03.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckers S, 2001. Neuroimaging studies of the hippocampus in schizophrenia. Hippocampus 11, 520–528. 10.1002/hipo.1068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckers S, Konradi C, 2014. GABAergic mechanisms of hippocampal hyperactivity in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res 10.1016/j.schres.2014.09.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoptman MJM, Zuo XNX, Butler PDP, Javitt DC, D’Angelo D, Mauro CJ, Milham MP, 2010. Amplitude of low-frequency oscillations in schizophrenia: a resting state fMRI study. Schizophr. … 117, 1–16. 10.1016/j.schres.2009.09.030.Hoptman [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA, 1987. The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 13, 261–276. 10.1093/schbul/13.2.261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh MT, Shao Y, Rosenzweig-Lipson S, Gallagher M, 2018. Treatment with levetiracetam improves cognition in a ketamine rat model of schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res 193, 119–125. 10.1016/J.SCHRES.2017.06.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuznetsova A, Brockhoff PB, Christensen RHB, 2017. lmerTest Package: Tests in Linear Mixed Effects Models. J. Stat. Softw 82, 1–26. 10.18637/JSS.V082.I13 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lenth R, 2018. emmeans: Estimated Marginal Means, aka Least-Squares Means. [WWW Document]. URL https://cran.r-project.org/package=emmeans

- Leucht S, Samara M, Heres S, Patel MX, Woods SW, Davis JM, 2014. Dose equivalents for second-generation antipsychotics: The minimum effective dose method. Schizophr. Bull 40, 314–326. 10.1093/schbul/sbu001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F, Lui S, Yao L, Hu J, Lv P, Huang X, Mechelli A, Sweeney JA, Gong Q, 2016. Longitudinal Changes in Resting-State Cerebral Activity in Patients with First-Episode Schizophrenia: A 1-Year Follow-up Functional MR Imaging Study. Radiology 279, 867–875. 10.1148/radiol.2015151334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman JA, Girgis RR, Brucato G, Moore H, Provenzano F, Kegeles L, Javitt D, Kantrowitz J, Wall MM, Corcoran CM, Schobel SA, Small SA, 2018. Hippocampal dysfunction in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia: a selective review and hypothesis for early detection and intervention. Mol. Psychiatry 23, 1764–1772. 10.1038/mp.2017.249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisman JE, Coyle JT, Green RW, Javitt DC, Benes FM, Heckers S, Grace AA, 2008. Circuit-based framework for understanding neurotransmitter and risk gene interactions in schizophrenia. Trends Neurosci. 31, 234–242. 10.1016/j.tins.2008.02.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lodge DJ, Grace AA, 2011. Hippocampal dysregulation of dopamine system function and the pathophysiology of schizophrenia. Trends Pharmacol. Sci 32, 507–513. 10.1016/j.tips.2011.05.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathalon DH, Sohal VS, G B, BJ R, RT C, J N, CA B, P T, Y H, 2015. Neural Oscillations and Synchrony in Brain Dysfunction and Neuropsychiatric Disorders. JAMA Psychiatry 72, 840. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugo M, Armstrong K, Roeske MJ, Woodward ND, Blackford JU, Heckers S, 2020. Hippocampal volume in early psychosis: a 2-year longitudinal study. Transl. Psychiatry 10, 306. 10.1038/s41398-020-00985-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugo M, Avery S, Armstrong K, Rogers BP, Vandekar SN, Woodward ND, Blackford JU, Heckers S, 2021. Anterior hippocampal dysfunction in early psychosis: a 2-year follow-up study. Psychol. Med 1–10. 10.1017/S0033291721001318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugo M, Rogers BP, Talati P, Woodward ND, Heckers S, 2015. Increased amplitude of low frequency fluctuations but normal hippocampal-default mode network connectivity in schizophrenia. Front. Psychiatry 6, 24. 10.3389/fpsyt.2015.00092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugo M, Talati P, Armstrong K, Vandekar SN, Blackford JU, Woodward ND, Heckers S, 2019. Hyperactivity and reduced activation of anterior hippocampus in early psychosis. Am. J. Psychiatry 176, 1030–1038. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2019.19020151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugo M, Talati P, Woodward ND, Armstrong K, Blackford JU, Heckers S, 2018. Regionally specific volume deficits along the hippocampal long axis in early and chronic psychosis. NeuroImage Clin. 20, 1106–1114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niessing J, Ebisch B, Schmidt KE, Niessing M, Singer W, Galuske RAW, 2005. Hemodynamic signals correlate tightly with synchronized gamma oscillations. Science (80-. ). 309, 948–951. 10.1126/science.1110948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez SM, Lodge DJ, 2014. New approaches to the management of schizophrenia: Focus on aberrant hippocampal drive of dopamine pathways. Drug Des. Devel. Ther 10.2147/DDDT.S42708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins DO, Leserman J, Jarskog LF, Graham K, Kazmer J, Lieberman JA, 2000. Characterizing and dating the onset of symptoms in psychotic illness: the Symptom Onset in Schizophrenia (SOS) inventory. Schizophr. Res 44, 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plassard AJ, Bao S, McHugo M, Beason-Held L, Blackford JU, Heckers S, Landman BA, 2021. Automated, open-source segmentation of the Hippocampus and amygdala with the open Vanderbilt archive of the temporal lobe. Magn. Reson. Imaging [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Power JD, Barnes KA, Snyder AZ, Schlaggar BL, Petersen SE, 2012. Spurious but systematic correlations in functional connectivity MRI networks arise from subject motion. Neuroimage 59, 2142–2154. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.10.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Provenzano FA, Guo J, Wall MM, Feng X, Sigmon HC, Brucato G, First MB, Rothman DL, Girgis RR, Lieberman JA, Small SA, 2020. Hippocampal Pathology in Clinical High-Risk Patients and the Onset of Schizophrenia. Biol. Psychiatry 87, 234–242. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2019.09.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purdon S, 2005. The screen for cognitive impairment in psychiatry (SCIP): administration manual and normative data. PNL Inc, Edmonton, Alberta. [Google Scholar]

- Ragland JD, Layher E, Hannula DE, Niendam TA, Lesh TA, Solomon M, Carter CS, Ranganath C, 2017. Impact of schizophrenia on anterior and posterior hippocampus during memory for complex scenes. NeuroImage Clin. 13, 82–88. 10.1016/j.nicl.2016.11.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schobel SA, Chaudhury NH, Khan UA, Paniagua B, Styner MA, Asllani I, Inbar BP, Corcoran CM, Lieberman JA, Moore H, Small SA, 2013. Imaging Patients with Psychosis and a Mouse Model Establishes a Spreading Pattern of Hippocampal Dysfunction and Implicates Glutamate as a Driver. Neuron 78, 81–93. 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.02.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schobel SA, Lewandowski NM, Corcoran CM, Moore H, Brown T, Malaspina D, Small SA, 2009. Differential targeting of the CA1 subfield of the hippocampal formation by schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 66, 938–946. 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholvinck ML, Maier A, Ye FQ, Duyn JH, Leopold DA, 2010. Neural basis of global resting-state fMRI activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 107, 10238–10243. 10.1073/pnas.0913110107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small SA, Schobel SA, Buxton RB, Witter MP, Barnes CA, 2011. A pathophysiological framework of hippocampal dysfunction in ageing and disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci 12, 585–601. 10.1038/nrn3085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talati P, Rane S, Kose S, Blackford JU, Gore J, Donahue MJ, Heckers S, 2014. Increased hippocampal CA1 cerebral blood volume in schizophrenia. NeuroImage. Clin 5, 359–364. 10.1016/j.nicl.2014.07.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talati P, Rane S, Skinner J, Gore J, Heckers S, 2015. Increased hippocampal blood volume and normal blood flow in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. - Neuroimaging 232, 219–225. 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2015.03.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamminga CA, Southcott S, Sacco C, Wagner AD, Ghose S, 2012. Glutamate dysfunction in hippocampus: Relevance of dentate gyrus and CA3 signaling. Schizophr. Bull 38, 927–935. 10.1093/schbul/sbs062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Y, Chen K, Zhou Y, Liu J, Wang Y, Driesen N, Edmiston EK, Chen X, Jiang X, Kong L, Zhou Q, Li H, Wu F, Wang Z, Xu K, Wang F, 2015. Neural activity changes in unaffected children of patients with schizophrenia: A resting-state fMRI study. Schizophr. Res 168, 360–365. 10.1016/J.SCHRES.2015.07.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Y, Zhou Q, Chang M, Chekroud A, Gueorguieva R, Jiang X, Zhou Y, He G, Rowland M, Wang D, Fu S, Yin Z, Leng H, Wei S, Xu K, Wang F, Krystal JH, Driesen NR, 2019. Altered functional connectivity and low-frequency signal fluctuations in early psychosis and genetic high risk. Schizophr. Res 210, 172–179. 10.1016/j.schres.2018.12.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor PA, Saad ZS, 2013. FATCAT: (An Efficient) Functional And Tractographic Connectivity Analysis Toolbox. https://home.liebertpub.com/brain 3, 523–535. 10.1089/BRAIN.2013.0154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomasi D, Wang GG, Volkow NDN, 2013. Energetic cost of brain functional connectivity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 110, 13642–13647. 10.1073/pnas.1303346110/-/DCSupplemental.www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.1303346110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tregellas JR, 2014. Neuroimaging biomarkers for early drug development in schizophrenia. Biol. Psychiatry 76, 111–119. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.08.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner JA, Damaraju E, van Erp TGM, Mathalon DH, Ford JM, Voyvodic J, Mueller BA, Belger A, Bustillo J, McEwen S, Potkin SG, Fbirn, Calhoun VD, 2013. A multi-site resting state fMRI study on the amplitude of low frequency fluctuations in schizophrenia. Front. Neurosci 7, 137. 10.3389/fnins.2013.00137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uludağ K, Roebroeck A, 2014. General overview on the merits of multimodal neuroimaging data fusion. Neuroimage 102, 3–10. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.05.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandekar S, Tao R, Blume J, 2020. A Robust Effect Size Index. Psychometrika 85, 232–246. 10.1007/S11336-020-09698-2/FIGURES/4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venables WN, Ripley BD, 2013. Modern applied statistics with S-PLUS. Springer Science \& Business Media. [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Shen Z, Huang P, Yu H, Qian W, Guan X, Gu Q, Yang Y, Zhang M, 2017. Altered spontaneous brain activity in chronic smokers revealed by fractional ramplitude of low-frequency fluctuation analysis: a preliminary study. Sci. Reports 2017 71 7, 1–7. 10.1038/s41598-017-00463-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D, 2001. Wechsler Test of Adult Reading. [Google Scholar]

- Woolard AA, Heckers S, 2012. Anatomical and functional correlates of human hippocampal volume asymmetry. Psychiatry Res. 201, 48–53. 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2011.07.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue T, Dong F, Huang R, Tao Z, Tang J, Cheng Y, Zhou M, Hu Y, Li X, Yu D, Ju H, Yuan K, 2020. Dynamic Neuroimaging Biomarkers of Smoking in Young Smokers. Front. Psychiatry 11, 663. 10.3389/FPSYT.2020.00663/BIBTEX [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan C-G, Craddock RC, Zuo X-N, Zang Y-F, Milham MP, 2013. Standardizing the intrinsic brain: towards robust measurement of inter-individual variation in 1000 functional connectomes. Neuroimage 80, 246–262. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.04.081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou QH, Zhu CZ, Yang Y, Zuo XN, Long XY, Cao QJ, Wang YF, Zang YF, 2008. An improved approach to detection of amplitude of low-frequency fluctuation (ALFF) for resting-state fMRI: Fractional ALFF. J. Neurosci. Methods 172, 137–141. 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2008.04.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.