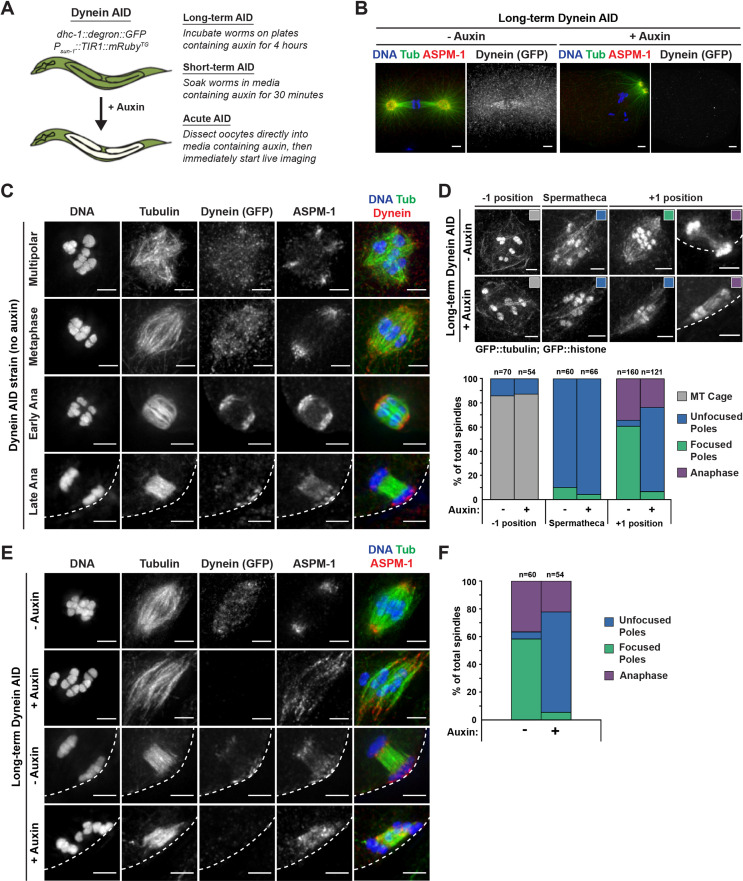

Figure 1. Dynein is required for acentrosomal pole focusing.

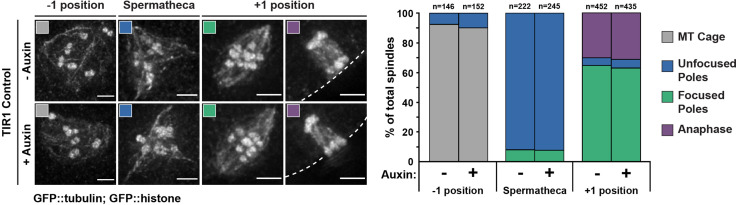

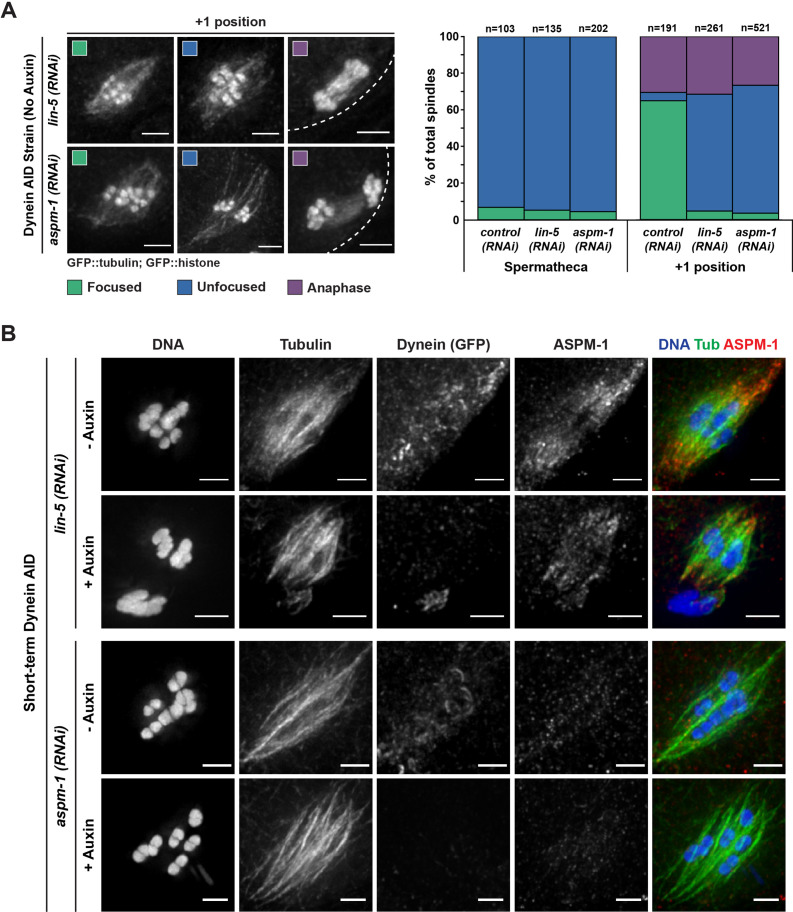

(A) Schematic representation of the Dynein auxin-inducible degron (AID) system for DHC-1 depletion in the C. elegans germ line. Methodologies for all three auxin treatments used in this study are depicted. (B) Immunofluorescence (IF) imaging of one-cell mitotically dividing embryos shows that auxin treatment causes efficient dynein depletion and canonical mitotic spindle defects (n = 22). Shown are tubulin (green), DNA (blue), ASPM-1 (red), and dynein (not shown in merge). (C) IF imaging of oocyte spindles in the Dynein AID strain shows that dynein is localized to the spindle, with increasing enrichment at acentrosomal poles at the anaphase transition; shown are tubulin (green), DNA (blue), dynein (red), and ASPM-1 (not shown in merge). Cortex is represented by the dashed line. (D) Representative images of oocyte spindles (GFP::tubulin and GFP::histone) in germline counting and corresponding quantifications; auxin treatment leads to splayed poles and spindle rotation defects. Cortex is represented by the dashed line. (E) IF imaging of Dynein AID conditions showing effects of 4 hr auxin treatment on metaphase (second row) and anaphase (bottom row); shown are tubulin (green), DNA (blue), ASPM-1 (red), and dynein (not shown in merge). ASPM-1 labeling supports initial observations of splayed poles seen in germline counting. (F) Quantifications of IF imaging shown in (E); meiotic spindles have significantly splayed poles upon auxin treatment. All scale bars = 2.5 µm. Controls for exposure to auxin plates can be found in Figure 1—figure supplement 1. Further experimentation with dynein mislocalization through aspm-1(RNAi) or lin-5(RNAi) can be found in Figure 1—figure supplement 2.