Abstract

Physician associates (PAs) are a new healthcare professional group in the UK. While PAs have been known as a stable but flexible workforce in the USA for over 50 years, little is known about their career paths in the UK’s NHS. A cross sectional online survey (January 2020 – May 2020) of graduates from the longest running UK PA course investigated stability and factors influencing job retention or movement. One-hundred and sixty-two (71%) graduates provided a full response. Descriptive analysis was by early graduates (2006–2013), mid-graduates (2014–2017) and recent graduates (2018–2020). Early and mid-graduates held their first jobs for a mean of 3 years. For early graduates, the longest held job was 11 years, with a mode of 7 years. Enjoyment of the work, learning opportunities and working with supportive consultants were the most highly rated factors in PA job retention.

KEYWORDS: physician associates, physician assistants, workforce, survey, careers

Introduction

The NHS is facing a quadruple challenge of improving patient care and population health with limited financial resources while also improving the working lives of health professionals.1, 2 Workforce stresses in the NHS have become even more pronounced during the pandemic.3 One solution to the long-standing problems of increasing patient demand combined with shortages in the medical profession has to been to introduce new roles with advanced clinical skills sometimes known as non-physician clinicians or advanced practice providers.4 In the UK, the government has supported established professions (eg nurses and physiotherapists) to become advanced clinical practitioners and introduced a new profession: physician associates (PAs; known as physician assistants in some countries).2 PAs are generalist healthcare professionals, medically trained at postgraduate level, who work alongside doctors to provide medical care as an integral part of the multidisciplinary team. PAs are dependent practitioners working with a dedicated medical supervisor but are able to work autonomously with appropriate support.5 The NHS in England (since 2008) and Scotland (2011) and, more recently, in Wales and Northern Ireland have supported the clinical training of PAs, to the extent that there are now 35 universities providing PA postgraduate courses and an estimated 2,850 UK qualified PAs (July 2021).6, 7

PAs have a history of 50+ years in the USA, where approximately 130,000 are currently employed across primary and secondary care.8 US PAs are a very stable workforce with the mean length of first jobs of 3.4 years, two-thirds remaining in the same specialty in the first decade after graduating and 51% remaining in the same specialty over their working careers.9, 10 There is currently no evidence from the UK as to whether PAs in the NHS demonstrate the same stability in their work careers. Our study was undertaken to gather this evidence.

While the Faculty of Physician Associates’ annual census provides information on the specialty in which PAs work, information is not available to consider career trajectories.11 There is also no information available regarding recruitment and retention patterns as PAs are not allocated a specific occupation code in the NHS Workforce Minimum Data Set.12 A key NHS workforce objective, before and since the pandemic has been to improve retention of all groups of staff.2, 13 A wide range of factors push and/or pull clinical professionals from and to jobs.14, 15, 16 This study investigated the career trajectories of PAs in the UK and factors that influence their retention and turnover. Consideration of these factors may help employers retain PAs in jobs.

The research questions addressed are:

-

•

how long do PAs spend in their first and subsequent job(s)

-

•

do PAs change specialties

-

•

what factors influenced PAs to stay in or leave jobs?

Methods

A cross-sectional web-based electronic survey was undertaken in spring 2020, of a purposive sample of graduates from the longest running PA course in the UK. It is reported here in accordance with the CHERRIES checklist.17

Sample

All graduates of the St George’s, University of London, physician associate course (2006–2019) who gave permission to be contacted via email to the course director for purposes of surveys and information sharing. The cohort size increased over time (range 9–70). The total number of graduates 2006–2019 was 255, and 229 (90%) gave permission to be contacted by email.

The graduates were invited to participate by the course director. Each graduate was sent a participant information sheet that detailed the purpose of the study, nature of the anonymous survey, anticipated time to complete, consent procedure, data protection procedures and the research team members. Each graduate was sent the web link to the closed survey. Three reminders to complete the survey were sent. Participation was voluntary and no incentives were offered. Of the 229 invitations sent, 162 full responses were received (70.7% completion rate). An additional 61 partial responses were submitted (26.6%) but were not included in the results. Because respondents were not identifiable, it is impossible to know if some of the partial responders later submitted a full response. We did not collect the numbers who viewed the website but did not complete any questions.

Data collection

An anonymous web survey (LimeSurvey) was used between January 2020 – May 2020. The survey questions were adapted from the published survey used in the USA with PAs and asked the respondents to report (using drop down lists of choices) each job they had held by specialty, type of contract and reason for leaving using the variables in the NHS minimum workforce data.10, 12 Each question offered a non-response option. A field for free text was offered for those wishing to provide more information or explanation. Each page requested data on an individual job and was adaptive in taking participants to the final pages of the survey on completing data on their current job. Participants could review their answers before submission but could not re-submit once submitted. The number of pages that participants viewed was dependent on the number of jobs they had held and, therefore, a completeness check was not offered to participants. The survey was piloted with PA academics who were not graduates of the course and then questions refined.

The survey requested basic demographic details (gender, ethnicity and age bands as used in the UK census) and did not request any identifying details such as name or date of birth. Participants self-assigned a unique six-digit identification on their survey.

Those respondents who wished to receive a copy of the findings were directed to a separate e-survey, unconnected with their responses, to leave contact details.

Data analysis

Anonymous data were downloaded from the survey site and stored on password protected university computers. Data were exported into MS Excel for storage and analysis. Apart from one very-early graduate, all respondents began working over an 11-year period, 2010 to 2020. To divide the graduate years as equally as possible, three groups were created of 4 years (2010–2013), 4 years (2014–2017) and 3 years (2018–2020). The one very-early graduate was included in the early graduate cohort to protect their identity in reporting details. Respondents were, therefore, classified into three groups (cohorts) for analysis:

-

•

early graduates: first job started 2006–2013

-

•

mid-graduates: first job started 2014–2017

-

•

recent graduates: first job started 2018–2020.

Quantitative data was analysed descriptively.

Ethics

The study was conducted in accordance with the Medical Research Council guidance and was approved by the university research ethics committee on 05 December 2019, reference number 19.0352.18

Results

Characteristics of respondents

Of the 162 respondents, the majority were women (81%), White (43%) and under 30 years old (51%). The majority were from the most recently graduated cohort (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of respondents

| Early graduates | Mid-graduates | Recent graduates | |

|---|---|---|---|

| First job started, year | 2006–2013 | 2014–2017 | 2018–2020 |

| Number of respondents and (response rate) per invitees, n (%) | 27/53 (51) | 52/86 (60) | 83/90 (92) |

| Gender, women:men, na | 21:4 | 41:9 | 70:10 |

| Age, na | |||

| Under 30 years | 2 | 28 | 52 |

| 30–39 years | 22 | 19 | 23 |

| 40–49 years | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| 50–59 years | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| Ethnicity, na | |||

| Asian | 6 | 17 | 19 |

| Black | 4 | 4 | 20 |

| White | 14 | 24 | 32 |

| Mixed | 0 | 3 | 2 |

| Other | 0 | 2 | 4 |

If indicated in response.

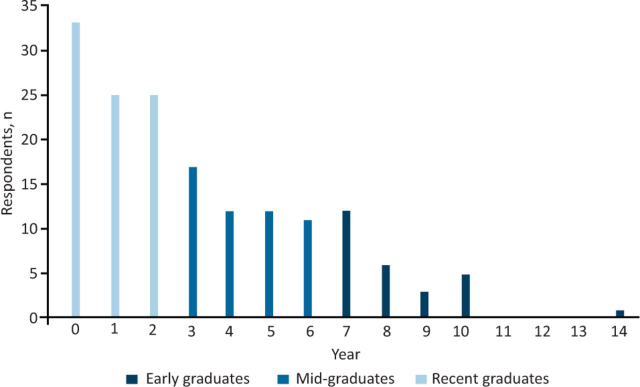

Time since graduating as a PA

The time since graduating as a PA ranged from under 12 months to 14 years, with 7 years as the mode in the early graduate cohort, 3 years in the mid-graduate cohort and under 12 months in the recent graduate cohort (Fig 1).

Fig 1.

Years since graduation as a physician associate.

We report on the research questions, comparing cohorts where appropriate.

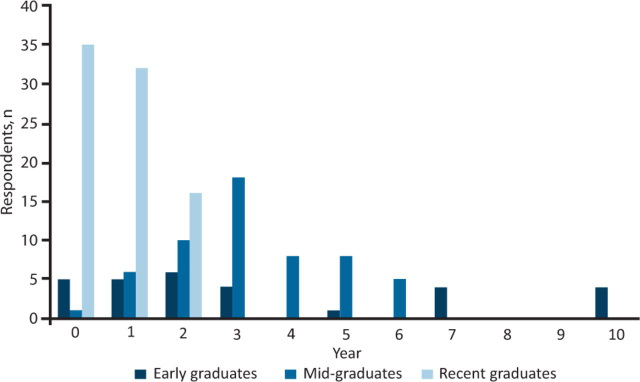

Years in and specialty of first PA job

The mean number of years spent in the first job as a PA was 3 years for early graduates (range <1–10); 3 years for mid-graduates (range <1–6) and 0.8 years for recent graduates (range <1–2; Fig 2). Three early graduates were still in their first jobs at the time of the survey.

Fig 2.

Years in first physician associate job.

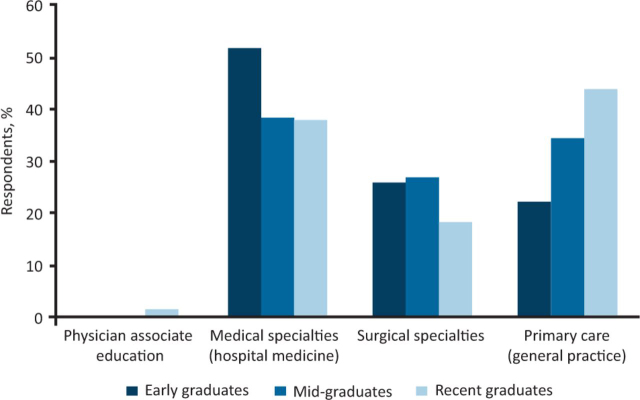

More PAs were employed in general practice (family medicine) for their first job in the recent graduate cohort than the previous cohorts (Fig 3). Surgical specialties were categorised together. The hospital medical specialties in which PA graduates were employed for the first job are shown in Box 1.

Fig 3.

Specialty of first job.

Box 1.

The hospital medical specialties in which physician associate graduates obtained first jobs

| Acute medicine |

| Cardiology |

| Critical care |

| Dermatology |

| Gastroenterology |

| General medicine |

| Genitourinary medicine |

| Geriatrics |

| Gynaecology |

| Haematology |

| Infectious diseases |

| Nephrology |

| Neurology |

| Oncology |

| Paediatrics |

| Palliative medicine |

| Respiratory medicine |

| Sexual and reproductive medicine |

Type of contract in first PA job

Compared with early graduates, both mid- and recent graduates were more likely to start work on a permanent contract (52% early; 87% mid- and 77% recent graduates). However, a greater percentage of recent graduates commenced their first job on a fixed-term contract than the mid-graduates.

PAs working outside of general practice are paid on the Agenda for Change (AfC) salary structure.19 In this study, most graduates employed in general practice reported salary using the ‘Other’ pay category, although some reported an equivalent AfC salary band. Of all respondents who started their first job on AfC, approximately 75% (range 74%–77%) started on AfC Band 7. Of those providing salary information in the Other category, the mean pay for their first job was £35,500 (early), £35,650 (mid-) and £35,400 (recent). These salaries are consistent with upper AfC Band 6.19

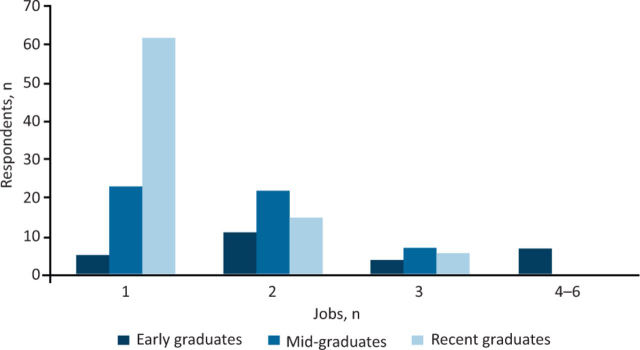

Maximum number of years in a job and total number of jobs

For PAs working 7–14 years, the longest-held jobs were 10 or 11 years, with a mode of 7 years. For PAs working 3–6 years, the longest-held jobs were 6 years, with a mode of 3 years. For PAs working 2 years or less, the longest-held jobs were 2 years, with a mode of 1 year.

The maximum number of PA jobs reported was six by a PA in the early graduate cohort ie over a period of up to 14 years (Fig 4). The majority (60%) of early graduates reported that they were still in their first or second job, similarly, the majority of mid-graduates (86%) were also still in their first or second job. Of the recent graduates, 75% were still in the first job.

Fig 4.

Total number of physician associate jobs since graduation.

Changing specialties

A PA qualification allows flexibility in moving between specialties. Among early graduates, 21 of 27 (78%) have worked in at least two different specialties, including PA education. Eighteen of 52 (35%) mid-graduates and 14 of 83 (17%) recent graduates have worked in at least two different specialties, despite being qualified for fewer years. Some graduates reported working in split jobs, even in the first job after qualifying, evidencing the flexible nature of the PA role.

Examples include two PAs who commenced their first jobs in paediatrics. One moved to acute medicine and the other to general medicine. Another PA reported working in surgical specialties, sexual and reproductive health, infectious diseases, cardiology, and PA education. Several of these jobs were short fixed-term jobs, requiring a move to a new job; the time in the longest-held job was over 7 years.

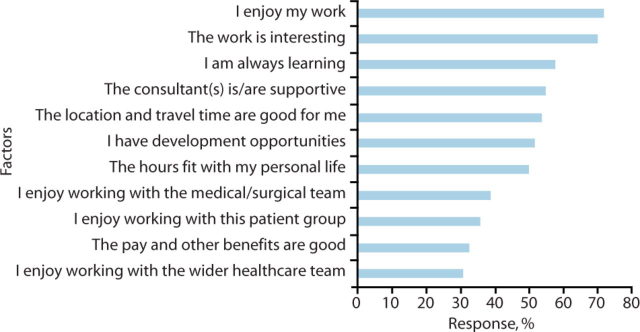

Reasons for remaining in and for leaving a job

Respondents were asked to select pre-defined factors that have kept them in their current jobs. Across the 160 responses, the three most common factors were ‘The work is interesting’ (70%), ‘I enjoy my work’ (72%) and ‘I am always learning’ (58%; Fig 5).

Fig 5.

Reasons for remaining in a job

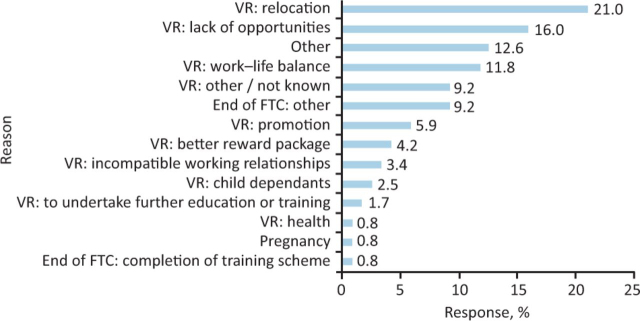

Respondents were asked to select pre-defined reasons for leaving a job. Across the 119 responses, the four most common reasons reported were ‘Relocation’ (21%), ‘Lack of opportunities’ (16%), ‘Other’ (13%) and ‘Work–life balance’ (12%; Fig 6). Ten per cent of all responses indicated that PAs left jobs due to ‘End of fixed-term contract’, whether due to the ‘End of a training scheme’ or ‘Other’.

Fig 6.

Reasons for leaving a physician associate job. FTC = fixed-term contract; VR = voluntary resignation.

All free text entries describing the ‘Other’ category are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

All free-text reasons for leaving jobs

Early graduates

|

Mid-graduates

|

Recent graduates

|

Discussion

This is the first study to present data on the careers and job stability of PAs in the UK. The respondents reflected the demographics of the national census in that the majority were women and in their 30s but differed such that those who were White were not in the majority.11 The survey found that the majority of early and mid-graduate PAs remained in their first job for a mean of 3 years. This is comparable to first-job duration reported in the USA and suggests that they offer stability in personnel in healthcare teams.9 This is also borne out by the length of time in subsequent jobs and compares favourably with other professions. Nurses in the UK report a mean of 2.4 jobs by their third year post-qualification.20 The UK foundation and speciality training programmes require doctors to frequently move between posts and hospitals in the years after gaining their medical degree.21 The frequency of employment under fixed-term contracts in the early graduate cohorts reflects the time when the profession was relatively unknown and clinicians were unclear as to the usefulness, the scope of practice and how to deploy PAs.

PA graduates were employed in their first jobs across a broad range of medical and surgical specialties, including general practice. Graduates of the mid- and recent cohorts were more likely to start their first jobs in primary care compared with the early cohort. There may be several factors contributing to this. The Department of Health (England) released policy support for PAs to be available to work in primary care and, more recently, to reimburse general practices for PA salaries (among other groups, such as first-contact physiotherapists).22, 23 In 2017, Health Education England requested that clinical training in primary care increase from 180 hours to 510 hours across the 2 years and this recommended change to the PA curriculum may have contributed to the increase in PAs starting work in general practice. The increase and expansion of PA programmes resulted in more PA student placements in primary care with potential demonstration of the benefits that PAs could bring to the workforce. Finally, initiatives and campaigns promoting the role of the PA in primary care were developed, alongside toolkits to help support the implementation of these initiatives.24, 25, 26

The majority of PA graduates report only one or two jobs, those longest qualified demonstrating a mode of 7 years in individual jobs. Most PAs in the earliest graduating cohorts have worked in at least two specialties. Nearly one-fifth of recent graduates have worked in two specialties. Some change in jobs or specialty is due to the use of fixed-term contracts. Ten per cent of respondents gave the reason for leaving as the end of a fixed-term contract. The percentage of early graduates reporting sequential jobs in more than two specialties is higher than that reported in the USA.10 This may reflect the newness of the profession, limited initial job availability and the use of short-term contracts rather than a long-term trend. It does, however, demonstrate the flexibility in career options and also in the flexible deployment of PAs with their generalist training.

Employers can benefit from understanding the reasons PAs stay in or leave jobs. Retaining staff is a major policy initiative in the NHS.27 Enjoyment of the work, learning opportunities and working with supportive consultants were the most highly rated factors in retaining PAs in their jobs. Supportive consultant supervisors and training opportunities have previously been reported as important to newly qualified PAs.28

The most commonly selected reasons for leaving jobs were relocation and a lack of opportunities. Relocation of relatively newly qualified health professionals out of London has long been recognised as an issue in the city, with lack of affordable housing as a key contributing factor that is again receiving policy attention.27, 29 Other factors pushing PAs from jobs reflect those reported by other health professionals.14, 15, 16 Experiencing a lack of development opportunities has previously been reported as a source of PA job dissatisfaction in the UK.30 Of the nine free-text reasons provided for leaving jobs, five were related to job opportunities or specialty/department changes, three were related to the job location or closure of the clinic and one specifically mentioned lack of staff and high stress levels.

These findings suggest that PA jobs with supportive supervising consultants or GPs, further training provision and development opportunities are likely to retain PAs in jobs. These are points for consideration in developing new PA job opportunities and for increasing PA retention.

Strengths and limitations

This is the first study of its kind in the UK investigating the career trajectories of PAs and the reasons for leaving or staying in jobs. While it is limited in that the sample is from one university and is smaller than hoped for due to incomplete responses, the use of a validated survey, together with respondents from different graduate groups and a response rate of over 70% gives confidence in the results. Further research is required to repeat on a larger scale to give a more global picture of the working trajectories of PAs across all four countries in the UK. A larger sample would enable the exploration of other questions, such as whether there are differences in career trajectories by gender and ethnicity and whether PAs remain local to their training placements. It would also allow more in-depth exploration of the interplay of factors retaining PAs in a job.

Conclusion

This study provides evidence for the first time that, despite being a new to the UK profession, PAs remain in their first jobs for a mean of 3 years. Stability in staffing is an important factor in providing quality healthcare and maintaining good working lives for other clinicians. The study also provides evidence that, over time, most PAs change specialties, suggesting their generalist training offers flexibility in their careers and flexibility in deployment for employing clinicians and managers. The results from this study can inform clinicians and employers about reasons that PAs stay in or leave jobs. This should help with solutions to retain PAs in jobs and where to potentially focus and provide further postgraduate education and support.

Declaration of interests

Jeannie Watkins is a founder and director of the recruitment organisation PAs Transforming Healthcare (PATH).

Acknowledgments

Our thanks go to all graduates of the St George’s, University of London, physician associate programme.

References

- 1.Bodenheimer T, Sinsky C. From triple to quadruple aim: care of the patient requires care of the provider. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12:573–576. doi: 10.1370/afm.1713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.NHS England . The NHS Long Term Plan. NHS; 2019. www.england.nhs.uk/long-term-plan [Accessed 23 September 2021] [Google Scholar]

- 3.NHS England . 2021/22 priorities and operational planning guidance. NHS; 2021. www.england.nhs.uk/publication/2021-22-priorities-and-operational-planning-guidance [Accessed 12 December 2021] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization . Global strategy on human resources for health: Workforce 2030. WHO; 2016. www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241511131 [Accessed 23 September 2021] [Google Scholar]

- 5.5 Faculty of Physician Associates,. Who are physician associates? FPA. https://fparcp.co.uk/about-fpa/Who-are-physician-associates [Accessed 23 September 2021].

- 6.Ritsema TS, Roberts KA, Watkins JS. Explosive growth in british physician associate education since 2008. J Physician Assist Educ. 2019;30:57–60. doi: 10.1097/JPA.0000000000000233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.7 Straughton K, Roberts K, Watkins J, Drennan VM, Halter M,. Physician associate profession in the UK: development, current status and the future. JAAPA in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.US Bureau of Labor Statistics . Occupational outlook handbook: physician assistants. USBLS; 2021. www.bls.gov/ooh/healthcare/physician-assistants.htm [Accessed 23 September 2021] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Quella A, Hooker RS, Zobitz JM. Retention and change in PAs’ first years of employment. JAAPA. 2021;34:40–43. doi: 10.1097/01.JAA.0000750972.64581.b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hooker RS, Cawley JF, Leinweber W. Career flexibility of physician assistants and the potential for more primary care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010;29:880–886. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.11 Faculty of Physician Associates,. FPA census. FPA. https://fparcp.co.uk/about-fpa/fpa-census [Accessed 23 September 2021].

- 12.NHS Digital . NHS occupation codes. NHS; 2021. https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/areas-of-interest/workforce/nhs-occupation-codes [Accessed 23 September 2021] [Google Scholar]

- 13.NHS England . NHS people plan. NHS; 2020. www.england.nhs.uk/ournhspeople/ [Accessed 23 September 2021] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Botezat A, Ramos R. Physicians’ brain drain - a gravity model of migration flows. Global Health. 2020;16:7. doi: 10.1186/s12992-019-0536-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Halter M, Boiko O, Pelone F, et al. The determinants and consequences of adult nursing staff turnover: a systematic review of systematic reviews. BMC Health Services Research. 2017;17:824. doi: 10.1186/s12913-017-2707-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coombs C, Arnold J, Loan-Clarke J, Bosley S, Martin C. Allied health professionals’ intention to work for the National Health Service: a study of stayers, leavers and returners. Health Serv Manage Res. 2010;23:47–53. doi: 10.1258/hsmr.2009.009019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eysenbach G. Improving the quality of Web surveys: the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES) J Med Internet Res. 2004;6:e. doi: 10.2196/jmir.6.3.e34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.UK Research and Innovation . Principles and guidelines for good research practice. UKRI; 2012. www.ukri.org/publications/principles-and-guidelines-for-good-research-practice [Accessed 23 September 2021] [Google Scholar]

- 19.NHS Employers . NHS terms and conditions pay poster 2020/21: Pay scales for the 2020/21 pay year. NHS; 2021. www.nhsemployers.org/publications/nhs-terms-and-conditions-pay-poster-202021 [Accessed 23 September 2021] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murrells T, Robinson S, Griffiths P. Job satisfaction trends during nurses’ early career. BMC Nurs. 2008;7:7. doi: 10.1186/1472-6955-7-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.21 General Medical Council,. Standards, guidance and curricula. GMC. www.gmc-uk.org/education/standards-guidance-and-curricula [Accessed 07 December 2021].

- 22.Department of Health. Hunt J. New deal for general practice. Gov.uk; 2015. https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20151007201412/https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/new-deal-for-general-practice [Accessed 23 September 2021] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Buchan J, Charlesworth A, Gershlick B, Seccombe I. A critical moment: NHS staffing trends, retention and attrition. The Health Foundation; 2019. www.health.org.uk/publications/reports/a-critical-moment [Accessed 23 September 2021] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Healthy London Partnership . Physician associates. Healthy London Partnership; 2016. www.healthylondon.org/resource/physician-associates [Accessed 30 November 2021] [Google Scholar]

- 25.NHS Health Education England . NHS; 2015. Primary Care Workforce Commission report is a foundation for the short and long term.www.hee.nhs.uk/news-blogs-events/hee-news/primary-care-workforce-commission-report-foundation-short-long-term [Accessed 30 November 2021] [Google Scholar]

- 26.26 NHS Health Education England,. Physician associates in primary care. NHS. www.hee.nhs.uk/our-work/primary-care/physician-associates-primary-care [Accessed 30 November 2021].

- 27.27 NHS England,. Looking after our people – retention. NHS. www.england.nhs.uk/looking-after-our-people [Accessed 12 December 2021].

- 28.Roberts S, Howarth S, Millott H, Stroud L. ‘What can you do then?’ Integrating new roles into healthcare teams: Regional experience with physician associates. FHJ. 2019;6:61–66. doi: 10.7861/futurehosp.6-1-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hutt R, Buchan J. Trends in London’s NHS workforce. The King’s Fund; 2005. [Accessed 07 December 2021] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ritsema TS, Roberts KA. Job satisfaction among British physician associates. Clin Med. 2016;16:511–513. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.16-6-511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]