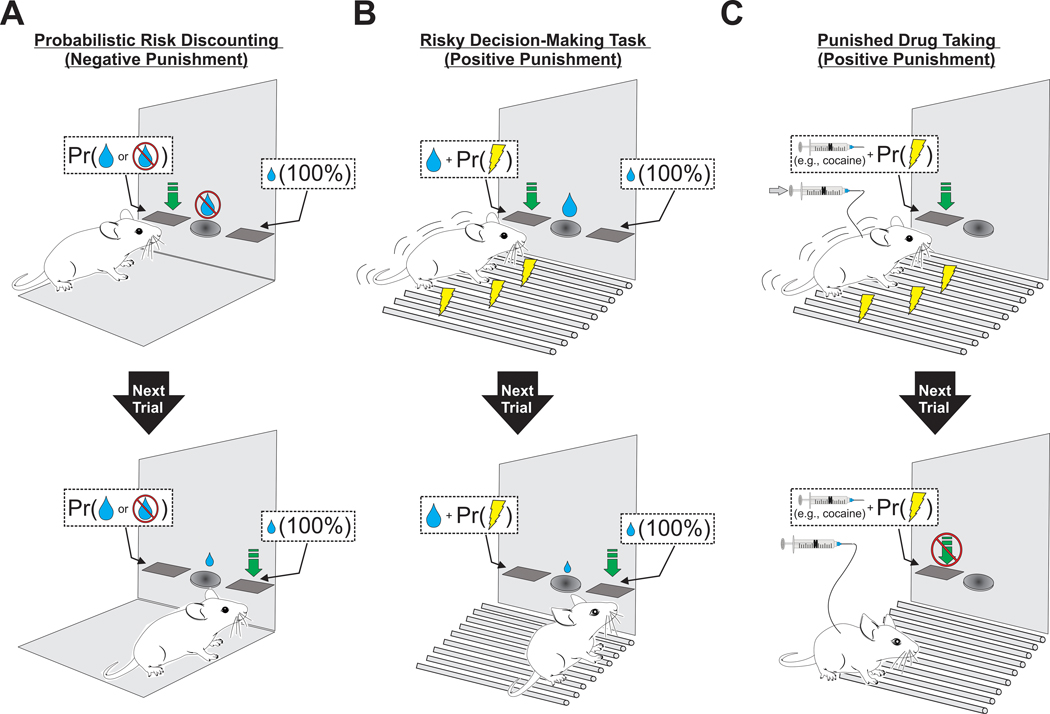

Figure 1.

Cartoon depictions of common methods for assessing risky reward seeking in rodents. (A) During performance of a negatively punished ‘probabilistic risk discounting’ task, animals learn that one lever is associated with a large amount of reward (depicted as a large liquid droplet) but is also associated with a particular probability (Pr) of reward omission (depicted as a droplet + ‘No’ symbol), while another lever guarantees delivery of a small amount of reward (depicted as a small liquid droplet). If the animal presses the large reward lever (green downward arrow) and reward is omitted, animals are more likely to switch away from the large reward option, and towards the small, certain option on the next trial (bottom panel). (B) As in A, an animal trained on a ‘risky decision-making’ task initially discriminates between two levers, one that delivers a large volume of liquid reward, and one that delivers a small volume. Selection of the large reward option is probabilistically (Pr) associated with footshock (yellow lightning bolts) punishment (top), which causes animals to flexibly shift their actions towards the guaranteed, safe option (bottom). (C) Positive punishment-based approaches have been used to examine the mechanisms contributing to ‘compulsive’ drug-related behavior. In this example, an animal self-administering cocaine (syringe) is subjected to probabilistically delivered footshocks concomitant with cocaine-seeking lever-presses (top). In animals sensitive to punishment, experience with footshock can cause animals to become more reticent, engaging in fewer bouts of drug-seeking (bottom). Pr (probability).