Abstract

During nervous system development, axons navigate complex environments to reach synaptic targets. Early extending axons must interact with guidance cues in the surrounding tissue, while later extending axons can interact directly with earlier “pioneering” axons, “following” their path. In Caenorhabditis elegans, the AVG neuron pioneers the right axon tract of the ventral nerve cord. We previously found that aex-3, a rab-3 guanine nucleotide exchange factor, is essential for AVG axon navigation in a nid-1 mutant background and that aex-3 might be involved in trafficking of UNC-5, a receptor for the guidance cue UNC-6/netrin. Here, we describe a new gene in this pathway: ccd-5, a putative cdk-5 binding partner. ccd-5 mutants exhibit increased navigation defects of AVG pioneer as well as interneuron and motor neuron follower axons in a nid-1 mutant background. We show that ccd-5 acts in a pathway with cdk-5, aex-3, and unc-5. Navigation defects of follower interneuron and motoneuron axons correlate with AVG pioneer axon defects. This suggests that ccd-5 mostly affects pioneer axon navigation and that follower axon defects are largely a secondary consequence of pioneer navigation defects. To determine the consequences for nervous system function, we assessed various behavioral and movement parameters. ccd-5 single mutants have no significant movement defects, and nid-1 ccd-5 double mutants are less responsive to mechanosensory stimuli compared with nid-1 single mutants. These surprisingly minor defects indicate either a high tolerance for axon guidance defects within the motor circuit and/or an ability to maintain synaptic connections among commonly misguided axons.

Keywords: nervous system development, axon guidance, axon navigation, pioneer, growth cone, trafficking, cdk5

Introduction

Correct development of any nervous system involves precise navigation of developing axons as they navigate through the surrounding environment, forming appropriate synaptic connections with cells in distant locations or within fasciculated nerve bundles. Early outgrowing axons use environmental guidance cues to navigate toward targets. These pioneering axons form pathways that later axons can follow, facilitating their navigation. This leads to the development of fasciculated nerve bundles within which neighboring axons can build en passant synapses between adjacent axons and dendrites. This “pioneer” and “follower” relationship is highly conserved; it is seen in a wide variety of organisms including grasshoppers, zebrafish, and mammals (Klose and Bentley 1989; Chitnis and Kuwada 1991; Rash and Richards 2001).

Guidance cues that regulate pioneer axon guidance have been identified in several model organisms including Caenorhabditis elegans. UNC-6/Netrin is a well described guidance molecule that is secreted ventrally, forming a dorso-ventral gradient that can attract or repel growth cones depending on growth cone receptor expression (Hedgecock et al. 1990). Two trans-membrane receptors recognize UNC-6/netrin: UNC-5 and UNC-40/DCC. Growth cones expressing UNC-40 alone are attracted to higher concentrations of UNC-6/netrin, while those expressing the UNC-40–UNC-5 dimer are repelled by receptor–target interactions (Wadsworth 2002).

In order for growth cones to respond correctly to guidance cues, numerous molecules must be transported from the cell body to the correct locations in the growth cone at the correct times. In vertebrates, the kinase CDK5 regulates this transport at multiple points; CDK-5 regulates vesicle transport to developing motoneuron terminals (Goodwin et al. 2012) and synaptic vesicle docking in mammals through physical interaction with the SNARE component Munc18 (Bhaskar et al. 2004).

The right ventral nerve cord (VNC) of C. elegans is the major anteroposterior axon tract. The right VNC tract is pioneered by the AVG axon, which extends posteriorly from the retrovesicular ganglion into the tail region. Later, command interneuron (CI) axons and embryonic motoneuron neurites extend along the path first forged by the AVG axon (Durbin 1987) (see Fig. 1). As they extend, they form fascicles with fellow VNC axons, synapsing en passant to form the motor circuit (Von Stetina 2006). If AVG is ablated before its axon extends, these following neurites make navigational errors as they extend, demonstrating the importance of the AVG axon in the development of the right VNC (Durbin 1987; Hutter 2003). The circuits formed during this critical developmental process will later regulate motoneuron activity, and incorrect right VNC pathfinding may disrupt the formation of the en passant synapses that coordinate both reactive and spontaneous movement (White et al. 1986).

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of relevant neurons and axons in the VNC. RIF (burgundy) axons pioneer the path from the retrovesicular ganglion (rvg) toward the nerve ring in the head. The AVG (green) axon pioneers the right VNC from the rvg, and the PVPR (orange) axon pioneers the left VNC from the posterior. Interneuron axons (red) from the nerve ring follow RIFR and RIFL into the rvg, then follow the AVG to continue posteriorly along the right VNC. Motoneurons (DA and DB in blue; DD and VD in purple) extend neurites anteriorly and posteriorly within the right VNC, and laterally toward the dorsal nerve cord (data not shown). A, anterior; P, posterior.

Given the crucial role AVG plays in setting the groundwork for the development of the right VNC, it is probable that several parallel systems have evolved to ensure that the AVG axon navigates correctly. These redundant regulatory pathways likely contribute to difficulties in identifying factors regulating AVG axon extension. To surmount these obstacles, we previously conducted a nid-1/Nidogen enhancer screen in an effort to identify novel factors regulating AVG axon guidance (Bhat and Hutter 2016). Nidogen is an evolutionarily conserved basement membrane protein with expression along the ventral midline. nid-1/Nidogen null mutants exhibit a 12% AVG misguidance phenotype, but are otherwise healthy (Kim and Wadsworth 2000).

From the nid-1 enhancer screen, we identified a novel allele of aex-3 (Bhat and Hutter 2016). aex-3 is a guanine nucleotide exchange factor and was shown to regulate AVG axon guidance through rab-3 and ida-1 associated vesicles, and to interact genetically with unc-5, the netrin receptor (Bhat and Hutter 2016). The docking of these vesicles would involve unc-18/Munc18, and may be regulated by cdk-5.

Here, we describe the identification, genetic interactions, phenotypic characterization, and behavioral impacts, of ccd-5, which is homologous to a CDK5 binding partner recently identified in humans, C2CD5/KIAA0528/CDP138 (Xu et al. 2014). The AVG axon shows navigation defects in 52% of nid-1 ccd-5(hd152) double mutants. We found that ccd-5 regulates AVG axon navigation in partnership with cdk-5, and further demonstrated genetic interaction with the aforementioned aex-3/rab-3 vesicle transport pathway and unc-5. nid-1 ccd-5 double mutants exhibit significant increases in midline crossings of motoneurons, CIs, and AVG. CI and DD/VD motoneuron axon midline crossings spatially coincide with AVG midline crossings, supporting the hypothesis that follower axon defects seen here are, at least in part, the result of these axons following a misguided AVG. Despite these dramatic axonal abnormalities, we did not observe obvious behavioral defects in these mutants when compared with controls. These results emphasize the robustness of the pioneer–follower relationship in the C. elegans motor circuit and bring to light a previously unexplored nuance in the genetic regulation of VNC axon guidance.

Materials and methods

Isolation and molecular identification of hd152

The hd152 allele of ccd-5 was isolated as described previously (Bhat and Hutter 2016). The hd152 mutant was backcrossed 4 times, and the whole genome was sequenced to identify changes in the coding regions of all genes. For sequencing worms were harvested from freshly starved plates and washed to remove any remaining E. coli. The worms were frozen at −80°C before genomic DNA extraction. After thawing, overnight proteinase K digestion and RNase A treatment, proteins were precipitated in 6M NaCl by centrifugation. DNA from the supernatant was resuspended and high molecular weight DNA was extracted from a 1% agarose gel using Qiagen’s QIAEX II Gel Extraction Kit. Sequencing libraries were made using Illumina’s Nextera XT library prep protocol and run on Agilent Bioanalyzer HS DNA chips for fragment size analysis. The strains were sequenced on a HiSeq 2500 2× 100 rapid run.

Single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) were called with the analysis pipeline and filters developed for the Million Mutation Project (Thompson et al. 2013). Briefly, Illumina HiSeq read pairs (2× 100bp) were aligned to the C. elegans reference genome version WS230 (www.wormbase.org) using the short-read aligner Phaster (Green P, personal communication). SNVs were then identified with SAMtools (Li et al. 2009) and annotated with a custom Perl script. Six different mutant strains originating from the same screen were sequenced and analyzed at the same time and SNVs called in more than one strain were discarded. The sequencing reads were later reanalyzed with a similar pipeline but using the BWA aligner giving similar final results.

The hd152 mutation was found to be linked to the X chromosome by crossing it with nid-1 males and then evaluating the phenotype of F1 males. The X chromosome was then mapped against the Hawaiian strain CB4856 using the DRA1 mapping system as described previously (Davis et al. 2005). A point mutation in F52H2.7 was the only candidate within the identified region. Complementation tests with F52H2.7 (gk700692) confirmed that hd152 is located in F52H2.7. This gene was registered as ccd-5.

Nematode strains and alleles used

The following alleles were used for phenotypic analysis: otIs182[inx-18::GFP] IV; hdIs30[glr-1::dsRed2]; hdIs24[unc-129::CFP, unc-47::DsRed2]; ccd-5(gk5256) X; ccd-5(gk5976) X. ccd-5(gk700952) X was used for complementation. The following alleles were used for genetic interaction studies: ccd-5(gk5256) X, rab-3(js49) II, unc-5(e53) IV, unc-18(e234) X, cdk-5(gm336) III, and nid-1(cg119) V. The strains were cultured and maintained at 20°C under standard conditions (Brenner 1974).

CRISPR/Cas9 allele gk5256 [loxP + Pmyo-2::GFP::unc-54 3' UTR + Prps-27::neoR::unc-54 3' UTR + loxP] X was produced as described previously (Au et al. 2019). The forward 5′-CAACGATTGTGTTTAGCCGTAG-3′ and reverse 5′-GTGTAGAGGAAATGACTGAGACTC-3′ primers amplify PCR fragments that are 5,443 bp in the WT allele and 7,434 bp in gk5256.

The 3,426 bp sequence between flanking sequences 5′-CGAAATGGAGACTACACACTTACCTGTATGACAAGGAGACGAACTAAAAC-3′ and 5′-TCTGGAAATGTAGATAATTATTCTTCGTATTTTCAGCTTACCAAACACAA-3′ was replaced by the repair cassette with the genotype described above.

CRISPR/Cas9 allele gk5976 [loxP + Pmyo-2::GFP::unc-54 3' UTR + Prps-27::neoR::unc-54 3' UTR + loxP] X was produced using the same strategy. A total of 1,962 bp were deleted and replaced by the above-mentioned CRISPR repair cassette, disrupting exons 1–8 between the flanking sequences of 5′-GGACTATACCTTAAAAAGCGCTTTCCTTTCCTTGTTCTCTTTTTCCACAG-3′ and 5′-TCTGGAAATGTAGATAATTATTCTTCGTATTTTCAGCTTACCAAACACAA-3′.

The following is the wild-type sequence including 50 base pairs upstream of gk70069 (G to A) and downstream of hd152 (T to G) point mutations, locations of which are capitalized: aaattcggcaagcttggaaaacggcaaattcggcaaatttgccctttccaGatttgtatggaattgttttatttttctgtcaaaaagTggtaaaaactcacagtcagtcttcaccgtaaacgttttttttctacgat

Construction of triple mutants

Triple mutants were constructed according to Iwasaki et al. (1997). The following primers were used to confirm the genotypes of strains containing the rab-3 (js49), cdk-5(ok626), and nid-1(cg119) mutants.

rab-3(js49): The forward 5′-CCAGCAGACAATACTTCGCC-3′ and reverse 5′-CTCCTTGGCTGATGTTCG-3′ primers were used to amplify a 610 bp PCR fragment from rab-3 genomic sequence including the change (G to A) in the rab-3(js49) mutant.

nid-1(cg119): The forward 5′-GTCCTCCCTCATCTGATGAATCG-3′ and reverse 5′-GAAACAGCAGGCCCAACTGATC-3′ primers were used to amplify PCR fragments from the nid-1 genomic sequence that are 3,846 bp in WT nid-1 and 717 bp in the nid-1(cg119) deletion mutation.

cdk-5(ok626): The forward 5′-GCGAGTATTACCTGAAAGCTTG-3′ and reverse 5′-CAATTGATATGTGGTCTGCCG-3′ primers were used to amplify PCR fragments from cdk-5 genomic sequence that are 1,202 bp in WT cdk-5 and 442 bp in the cdk-5(gm336) deletion mutation.

Phenotypic analysis of neuronal defects and microscopy

Axonal defects were scored with a Zeiss Axioscope (40× objective) in adult animals expressing fluorescent markers in respective neurons. Animals were immobilized with 10 mM sodium azide in an M9 buffer for 1 h and mounted on 2% agar pads before analysis. Images were obtained using a Nikon digital camera and assembled using Microsoft PowerPoint and ImageJ.

Behavioral methods

Locomotion and motor response to mechanosensory tap stimuli of C. elegans strains were assessed using the Multi-Worm Tracker (MWT; Swierczek et al. 2011). Petri plates for the behavioral experiments were prepared 48 h before tracking by evenly spreading 50 µl of E. coli OP50 on the plate using a sterilized Pasteur pipette. An age-synchronized population of each genotype was acquired by bleaching 15–30 gravid worms onto the Petri plate. Typically, this method generated 60–120 worms per plate. Plates were stored on a vibration-proof suspension shelf in a temperature and humidity-controlled room (20°C and 40%) until the tracking experiment 4 days (∼96 h) later. The MWT software (version 1.2.0.2) was used to record worms’ behavior and deliver stimuli. The plate was first mounted onto the tracking platform, and the plate lid was gently put on. Once the lid was on, the tracking session started. Worms were allowed to freely move on the Petri plate for 600 s, during which morphological and locomotor data were collected. Starting from 600 s, 30 mechanosensory stimuli were delivered by a solenoid tapping to the side of the Petri plate every 10 s, and tap response data were collected. The tracking session was terminated 10 s after the last tap. During the entire tracking session, animals’ behavior was recorded at a rate of ∼20 frames per second. Tracking of different strains was rotated to minimize the impact of time-sensitive factors. No blinding procedure was implemented as the MWT uses machine-vision to record behavior objectively.

The MWT data were first analyzed using Choreography (Swierczek et al. 2011). In Choreography (version 1.3.0_r1035), a “–shadowless, –minimum-move-body 2, –minimum-time 20” filter was applied to restrict the analysis to worms that traveled at least 2 body lengths and were tracked for at least 20 s; The MeasureReversal plugin was used to identify responses occurring within 1 s (dt = 1) of stimulus onset. Custom Matlab scripts were used to organize the data and compute the population statistics. Worms’ locomotion was binned together every 10 s, and the proportions of time worms spent on forward locomotion and average locomotion speed were calculated. Worms typically respond to mechanosensory taps by initiating an episode of backward locomotion, before they change direction and move forward again. The probability, duration, and speed of the reversal response to taps were measured. Habituation scores of response probability, duration, and speed were calculated by the % change from initial response level to the final response level, represented by an average of the last 3 responses.

Statistical analysis

We used chi square tests to assess the statistical significance of differences in penetrance on axon guidance defects. One-Way ANOVAs with Tukey’s HSD post hoc test was used to assess significance of variation in behavioral responses.

Results

hd152 is an allele of the uncharacterized gene ccd-5

We identified the allele hd152 in a nid-1 enhancer screen for AVG axon navigation defects. hd152 nid-1 double mutants exhibit a 52% AVG midline crossover defect (CO) penetrance (Table 1). ccd-5(hd152) single mutants do not have significant AVG defects (Table 1). We mapped hd152 to the left arm of the X chromosome, and whole-genome sequencing identified a point mutation in F52H2.7, which we named ccd-5 (Fig. 2). A strain containing a point mutation 9 base pairs downstream of ccd-5(hd152), ccd-5(gk700962), was available from the Million Mutation Project (Thompson et al. 2013). ccd-5(gk700962) nid-1 animals exhibit a 38% AVG CO penetrance. Complementation tests confirmed that gk700962 and hd152 are alleles of the same gene (Table 1). The Wormbase gene prediction at the time of these experiments suggested that both hd152 and gk700962 were located in an exon. However, when we isolated a ccd-5 cDNA we discovered that these 2 mutations are not in the coding region of the gene. Later Wormbase releases indicated that these mutations indeed are in an intron (Fig. 2). Since hd152 and gk700962 are in an intron, we hypothesized that these mutations might negatively affect ccd-5 gene expression. However, qPCR experiments showed that the mRNA levels of ccd-5 in hd152 and gk700962 mutants are not significantly different from wild-type (data not shown). At this point, we do not know how these mutations affect ccd-5 function. To confirm that ccd-5 is the gene responsible for our observed phenotype, we generated a deletion allele. ccd-5(gk5256) contains a 3.4 kb deletion removing exons 1 through 12 (Fig. 2). Homozygous nid-1 ccd-5(gk5256) mutants exhibit 44% penetrant AVG CO defects (Table 1). However, ccd-5(gk5256) deletes intron 9, where hd152 and gk700962 are located. This raises the possibility that some element in intron 9 that does not affect ccd-5 function, such as an unidentified noncoding RNA, might be responsible for the phenotype we observed. We therefore created another allele, gk5976, which eliminates exons 1–8 but leaves intron 9 intact (Fig. 2). nid-1 ccd-5(gk5976) double mutants show 53% AVG defects (Table 1). These results strongly suggest that the defects we observed are indeed due to a lack of ccd-5 function.

Table 1.

Penetrance of AVG defects in ccd-5 mutants.

| Genotype | % AVG CO defects | n |

|---|---|---|

| otIs182 [Pinx-18::GFP] | 14 | 200 |

| nid-1; otIs182 | 20 | 200 |

| ccd-5(700962); otIs182 | 22 | 250 |

| ccd-5(gk5256); otIs182 | 14 | 100 |

| ccd-5(gk5976); otIs182 | 16 | 100 |

| nid-1; ccd-5(hd152) hdIs51a | 52b | 100 |

| nid-1; ccd-5(gk700962); otIs182 | 38b | 350 |

| nid-1; ccd-5(gk5256); otIs182 | 44b | 100 |

| nid-1; ccd-5(gk5976); otIs182 | 53b | 120 |

| nid-1; ccd-5(gk700962)/ccd-5(hd152) hdIs51a | 42b | 100 |

hdIs51[odr-2::tomato] is an AVG marker with 0% AVG defect penetrance (n = 117). It is closely linked to ccd-5.

P < 0.01 when compared with nid-1; otIs182; chi square test.

Fig. 2.

Exon–intron structure of the ccd-5 gene showing the location of the mutations. Exons are represented as boxes, introns are represented as connecting lines. Blue exons code for the highly conserved C2 calcium binding domain needed for membrane interaction. The 4 ccd-5 alleles discussed are shown: hd152 is a T to G point mutation at position 2570136 X, gk700962 is a G to A point mutation at 2570127 X. gk5256 is a deletion that removes most of exons 1–12, gk5976 is a deletion that removes most of exons 1–8 (see Materials and Methods section for details).

ccd-5 shares 68% sequence similarity with its human homolog, C2CD5 (also known as KIAA0528 or CDP138). ccd-5 codes for an 876 amino acid protein with a single C2 domain at the carboxyl end. C2 domains are lipid-binding domains that target proteins to cell membranes (Zhang and Aravind 2010), so CCD-5 may play a role in membrane localization of binding partners. During embryogenesis, ccd-5 is expressed in all tissues including the nervous system (Cao et al. 2017).

nid-1 ccd-5 animals exhibit VNC axon navigation defects

To characterize the VNC axon guidance defects of ccd-5 mutants in more detail, we produced a series of nid-1 ccd-5(gk5256) strains that expressed fluorescent proteins in specific types of neurons. We used the ccd-5(gk5256) allele for a detailed analysis, because it deletes most of the coding part of the gene and represents the most convincing complete loss of function allele of ccd-5. We assessed the effects of these mutations on AVG axons, CI axons, and motoneuron (MN) neurites.

AVG axon defects

In wild type, the AVG cell body is in the retrovesicular ganglion, at the anterior end of the VNC. A short neurite sometimes extends anteriorly from the AVG cell body to the anterior-most point of the retrovesicular ganglion within the right VNC. A much longer neurite extends posteriorly within the right VNC terminating in the tail. AVG navigation defects in nid-1 ccd-5 and nid-1 mutants are quantified in Fig. 3a and depicted in Fig. 3b. Neither the parental marker strain nor the ccd-5 single mutant strain did exhibit defect penetrances >5% (data not shown).

Fig. 3.

AVG axon guidance defects in nid-1 ccd-5 double mutants. a) Penetrance for each AVG phenotype in nid-1 ccd-5 (green) or nid-1 (gray). N > 100, **P < 0.005 (chi square test). b) Representative images of nid-1 ccd-5 mutants exhibiting various phenotypes. Arrows point to crossovers. Marker used: Pinx-18::GFP. Scale bar: 10 μm.

Fifty percentage of nid-1 ccd-5 mutant worms exhibited AVG axon navigation defects. The most common defect observed was the AVG axon crossing the midline from the right to the left VNC (“cross left” in Fig. 3). This defect, which occurred in 39% of nid-1 ccd-5 animals, was significantly more penetrant compared with 18% defects in nid-1 animals (P < 0.0005). In 9% of nid-1 ccd-5 mutants AVG axons crossed the midline multiple times (“multiple CO” in Fig. 3), and in 6% of nid-1 ccd-5 mutants the AVG axon extended initially into the left VNC and then crossed the midline to rejoin the right VNC (“start left” in Fig. 3). Neither of these phenotypes were observed in nid-1 single mutants.

We also observed three rare phenotypes that did not significantly differ in penetrance between nid-1 and nid-1 ccd-5 but were not observed in the parental marker strain or in ccd-5 single mutants. In 2% of nid-1 ccd-5 double mutant animals and 4% of nid-1 animals AVG axons navigate away from the VNC laterally, often branching erratically at the lateral apex, and then return to the VNC (“leave/branch” in Fig. 3). We also observed two AVG cell body positioning defects, “cell body lateral” [nid-1 ccd-5 (4%) and nid-1 (1%)] and “cell body posterior” [nid-1 ccd-5 (10%) and nid-1 (5%)]. In both cell body positioning defects, the AVG cell extends neurites along the full length of the right VNC. When the AVG cell body is located posterior to the retrovesicular ganglion, an abnormally long apical neurite extends anteriorly toward the ganglion. When located lateral to the right VNC, it extends an axon to the VNC, where it branches to create this apical neurite. Coexpression of fluorescent markers in AVG and CI shows this apical neurite is extending to the RIF cell bodies in the retrovesicular ganglion (Fig. 3b, “cell body posterior” insert), with which AVG is known to synapse (White et al. 1986).

CI axon defects

CI axons extend from the nerve ring into the VNC bilaterally. At the retrovesicular ganglion, all CI axons on the left side cross the midline and enter the right VNC, where they remain as they extend posteriorly (Fig. 1). We used a glr-1::mCherry marker to visualize CI axon placement along the VNC in ccd-5 mutant animals, nid-1 single mutants, nid-1 ccd-5 double mutants, and a parental control strain. Though a variety of defects were observed in these lines, we chose to only analyze midline crossover defects for this and all follower axon cell types. The parental control and the ccd-5 single mutants both exhibited <5% midline crossover defect penetrance (data not shown). CI navigation defect penetrance in nid-1 and nid-1 ccd-5 mutant animals are compared in Fig. 4a and assessed phenotypes are shown in Fig. 4b.

Fig. 4.

CI axon guidance defects are elevated in nid-1 ccd-5 double mutants compared with nid-1 single mutants. a) Penetrance for each phenotype in nid-1 ccd-5 (red) or nid-1 (gray). N > 100, **P < 0.005 (chi square test). Defects in ccd-5 single mutant and parental control line are <5% (data not shown). b) Images of representative nid-1 ccd-5 mutants. Arrows point to crossovers. “V” indicates location of vulva where present. Marker used: Pglr-1::mCherry. Scale bar: 20 μm.

In nid-1 single mutants, CI axons cross the midline in 23% of individuals, and in nid-1 ccd-5 double mutants this occurs in 41% of individuals (N > 100 for each group, P < 0.0005). In nid-1 ccd-5 double mutants, two-thirds of these crossovers involve all CI axons in the right VNC crossing the midline as a single fascicle, which we call a “fasciculated crossover.” One-third of CI crossover defects seen involved single or a subset of axons defasciculating from other CI axons as they cross the midline, which we call a “defasciculated crossover.” In contrast, the ratio of fasciculated to defasciculated CI crossovers in nid-1 single mutants is closer to 1:1. The significant increase of CI midline crossovers in nid-1 ccd-5 double mutants compared with nid-1 single mutants is fully attributable to fasciculated CI crossovers, suggesting that ccd-5 affects CI axon guidance by influencing the CI fascicle as opposed to individual CI axons.

DD/VD motor neuron defects

The cell bodies of the DD and VD motoneurons are located along the ventral midline. Neurites extend from the cell bodies into the right VNC. Commissures branch off and grow circumferentially to the dorsal nerve cord (White et al. 1986; Durbin 1987; Von Stetina 2006). We used an unc-47::DsRed marker to visualize DD/VD neurite placement along the VNC in ccd-5 mutant animals, nid-1 single mutants, nid-1 ccd-5 double mutants, and a parental control strain. Though a variety of defects were observed in these lines, we chose to only analyze midline crossover defects for this and all follower axon cell types. DD/VD defect penetrance in these mutant lines are compared in Fig. 5a, and representative images of phenotypes assessed are shown in Fig. 5b.

Fig. 5.

DD/VD motoneuron axon guidance defects in ccd-5 mutants. a) Penetrance for each phenotype in ccd-5 (light purple), nid-1 ccd-5 (dark purple), nid-1 (gray), and parental marker strain (MS: white). N > 100, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.0001 (chi square test). B) Images of representative nid-1; ccd-5 mutants exhibiting quantified phenotypes (bottom). Arrows point to crossovers. Marker used: Punc-47::DsRed2. Scale bar 10 μm.

In nid-1 ccd-5 double mutants, 49% of individuals have neurites that cross from the right to the left VNC. This penetrance is significantly higher compared with 30% defects in nid-1 single mutants, 30% in ccd-5 single mutants, and 19% in the parental marker strain (N > 100 for each group, P < 0.0001). We assessed whether DD/VD neurites crossing the midline were more likely to do so while fasciculated or to defasciculate from other DD/VD neurites as they cross (Fig. 5a). We found that the ccd-5 mutation significantly increased both fasciculated and defasciculated crossovers, with or without nid-1 (P < 0.05). In turn, the nid-1 null mutation increased rates of fasciculated DD/VD crossovers with and without ccd-5, but the defasciculated crossover rate was not different in nid-1 single mutants when compared with control (Fig. 5a). In contrast, the penetrance of defasciculated crossovers in the nid-1 ccd-5 mutant is significantly higher than in the single mutants (Fig. 5a). In summary, nid-1 ccd-5 double mutants show significantly elevated rates of DD/VD crossovers when compared with ccd-5 or nid-1 single mutants, and ccd-5 single mutants have increased incidence of crossovers when compared with the parental control line.

DA/DB motor neuron defects

The cell bodies of the DA and DB motoneurons are also located along the ventral midline, and DA and DB neurites extend into the right VNC (White et al. 1986; Durbin 1987; Von Stetina 2006). We used an unc-129::CFP marker to visualize DA/DB neurite placement along the VNC in ccd-5 mutant animals, nid-1 single mutants, nid-1 ccd-5 double mutants, and a parental control strain. Though a variety of defects were observed in these lines, we chose to only analyze midline crossover defects for this and all follower axon cell types (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

DA/DB motoneuron axon guidance defects in ccd-5 mutants. Penetrance for each phenotype in ccd-5 (light blue), nid-1 ccd-5 (dark blue), nid-1 (gray), and parental marker strain (MS: white). N > 100, *P<0.05, **P < 0.0001 (chi square test).

In nid-1 single mutants, midline crossovers were seen in 26% of individuals, while this was true for 59% of nid-1 ccd-5 double mutants (N > 100 for each group, P < 0.0001). We again differentiated between fasciculated crossovers in which all neurites cross the midline together, and defasciculated crossovers in which a subset of neurites leaves others behind in the right VNC to cross the midline into the left VNC. In nid-1 single mutants, 18% of individuals had DA/DB axons cross from the right to the left VNC while remaining fasciculated, and 17% had crossover events in which a subset of DA/DB axons defasciculated from others as they crossed the midline. In nid-1 ccd-5 double mutants, fasciculated midline crossovers were seen in 56% of individuals, significantly more than seen in nid-1 single mutants (P < 0.0001), and accounting for essentially all defective individuals. The number of nid-1 ccd-5 mutants with defasciculated crossovers does not significantly differ from that of nid-1 single mutants; the majority of individuals with defasciculated crossovers also had fasciculated crossovers at other regions along the VNC. ccd-5 single mutants exhibited increased DA/DB crossover incidences when compared with parental controls, but only in the case of fasciculated defects (P < 0.05). In summary, ccd-5 significantly elevated rates of DA/DB midline crossovers, both with and without nid-1. This was largely due to an increase in DA/DB neurites crossing the midline together as a single fascicule.

Follower axon defects result from AVG axon defects

As described above, follower axons in the VNC are misguided in the absence of ccd-5. These defects might arise from CI and MN axons following a misguided AVG axon, or they could be caused by the absence of ccd-5 from some other pathway, independent of AVG. To determine to what extent follower defects are the result of AVG pioneer defects in the absence of ccd-5, we assessed whether midline crossing defects in each follower axon type corresponded spatially with AVG midline crossing defects. We assessed 2 classes of follower axons, CI axons and DD/VD axons. In each case, we categorized each crossover event as either “with AVG,” meaning that the AVG axon and some or all follower axons crossed the midline at the same point and seemingly in physical contact; or “independent,” meaning that the axons crossed the midline without close proximity to the other axon type being observed. We were also interested to see whether follower axons of each class were more likely to defasciculate from other axons of their own class to cross with AVG or without it. To this end, we distinguished between “fasciculated” crossovers; in which all axons of a cell type cross the midline together, and “defasciculated” crossovers; in which a subset of an axon type leaves the larger fascicle when crossing the midline. Examples of assessed phenotypes are shown in Fig. 7 (AVG and CI) and Fig. 8 (AVG and DD/VD). These findings are summarized in Fig. 9.

Fig. 7.

CI crossover defects correlated with AVG crossovers. AVG (green) and CI (red) in nid-1 ccd-5 mutants. a) Normally, AVG and CI axons fasciculate in the right VNC. b) Fasciculated CI cross with AVG. c) Defasciculated CI cross with AVG. d) Independent AVG crossover. e) Independent defasciculated CI crossover. Arrows mark crossover. Arrows point to crossovers. Location of vulva indicated with “V.” Markers used: Pglr-1::mCherry and Pinx-18::GFP. Scale bar: 20 μm.

Fig. 8.

DD/VD crossover defects correlated with AVG crossovers. AVG (green) and DD/VD (purple) in nid-1 ccd-5 mutants. a) Normally, AVG and DD/VD axons fasciculate in the right VNC. b–e) Examples of 4 different DD/VD crossover types assessed. Open arrows: DD/VD defasciculation. Arrows point to crossovers. Location of vulva indicated with “V.” Markers used: Punc-47::DsRed2 and Pinx-18::GFP. Scale bar: 20 μm.

Fig. 9.

CI and DD/VD follow AVG across the midline. Graphs showing correlation between AVG and follower axon crossovers. Follower axon crossovers in nid-1 ccd-5 (color) and nid-1 (gray) are shown, differentiating between: crossovers coinciding with AVG crossovers (“with AVG”) vs separate crossovers (“independent”), and crossovers that result is a split of the follower axon fascicle (defasciculated) vs a single fascicle containing all follower axons (fasciculated). a) CI crossover penetrance in each category. b) DD/VD crossover penetrance in each category. **P < 0.005 (chi square test).

In the case of CI axons, midline crossover defects were exclusively fasciculated. The increase in fasciculated CI crossovers with AVG seen in nid-1 ccd-5 mutants when compared with the nid-1 single mutants was able to account for all the differences between these 2 lines. No significant increases were observed in independent CI crossovers or in defasciculating CI crossovers. Thus, the ccd-5 associated increase in overall CI crossovers can be fully attributed to events in which all CI follow AVG as it aberrantly crosses the midline.

Unlike in CI, we observed an overall increase in defasciculated DD/VD midline crossovers in nid-1 ccd-5 double mutants when compared with nid-1 single mutants. This was true for independent and AVG associated crossovers. There was also a significant increase in fasciculated DD/VD axons crossing the midline with AVG, but not independently. We conclude that, while the effects of ccd-5 on AVG influence the guidance of the DD/VD fascicle as a unit, ccd-5 further influences DD/DV axon guidance independent of its follower relationship with AVG. This potentially more direct effect of ccd-5 on DD/VD axon guidance is seemingly associated with defasciculation of DD/VD axons from the larger fascicle.

In summary, introduction of the ccd-5 null mutation in a nid-1 null background significantly and specifically increases the likelihood of CI and DD/VD follower axons to cross the midline with AVG while remaining fasciculated to other follower axons. These results support the premise that AVG defects cause follower axon defects due in large part to the pioneer—follower relationship. Our results also establish a role for ccd-5 in DD/VD neurite fasciculation and guidance independent of AVG.

ccd-5 interacts genetically with vesicle transport associated genes

The vertebrate homolog of ccd-5, C2CD5, was identified as a CDK5 binding partner (Xu et al. 2014). The nid-1 ccd-5 and nid-1 cdk-5 double mutants have comparable AVG CO defects (Fig. 10), suggesting that cdk-5 and ccd-5 have a similar impact on AVG axon guidance. To determine if cdk-5 and ccd-5 act together to regulate AVG axon guidance, we evaluated defects in nid-1 cdk-5 ccd-5 triple mutants. We found that the defects in this triple mutant were not enhanced compared with either double mutant (Fig. 10). This suggests that ccd-5 and cdk-5 are acting in the same genetic pathway.

Fig. 10.

ccd-5 and cdk-5 genetically interact with unc-18, rab-3, and unc-5. AVG navigation defects in double and triple mutants. All double and triple mutants shown are significantly (P < 0.005, N > 100) more affected than nid-1 single mutants or parental marker strain (MS), and do not significantly differ from each other. None of the single mutants show significantly elevated AVG defects.

There are several ways in which CDK-5 and its homologs are known to regulate axon extension and/or navigation in a variety of models (discussed below). One regulatory pathway in mammals involves direct interaction of CDK5 with Munc18, resulting in the release of the SNARE complex and vesicle exocytosis (Bhaskar et al. 2004). The C. elegans Munc18 homologue is unc-18. unc-18 single mutants do not exhibit elevated AVG defect rates, but nid-1 unc-18 double mutants do. We observed no increase in axon navigation defects in the triple mutant nid-1 unc-18 cdk-5 when compared with nid-1 unc-18 or nid-1 cdk-5 double mutants. This suggests that unc-18 and cdk-5 act in the same pathway. Therefore, we conclude that ccd-5, unc-18, and cdk-5 function together to support accurate AVG axon navigation.

We previously identified an allele of aex-3, which affects AVG axon guidance through interaction with rab-3 and unc-5 in a nid-1 null background (Bhat and Hutter 2016). UNC-18 is known to regulate exocytosis of RAB-3 associated vesicles (Graham et al. 2011). To determine whether ccd-5 and cdk-5 have a place within this previously described pathway, we evaluated nid-1 ccd-5 rab-3 and nid-1 cdk-5 unc-5 triple mutants. Both triple mutants exhibited AVG defects similar to the corresponding double mutants, suggesting that these genes all act in the same genetic pathway.

Behavioral defects in nid-1 ccd-5 double mutants

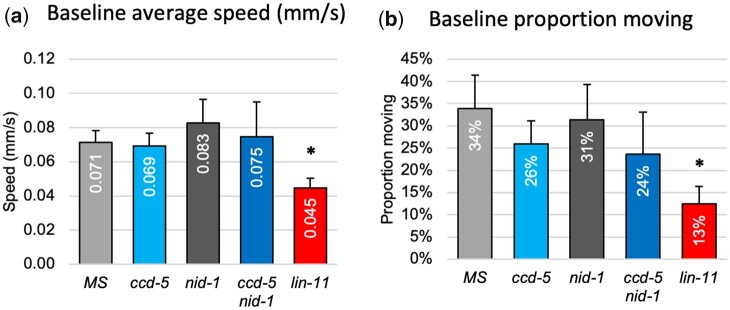

CI and motoneurons that extend neurites along the right VNC regulate complex behavioral output. To do so, they must be in physical contact with synaptic partners within the right VNC so they can form appropriate synapses. The navigation errors described above result in VNC disorganization, which may impact these neurites’ ability to meet synaptic partners, and thus may have wide reaching impacts on motor function in adult animals. We used the MWT (Swierczek et al. 2011) to assess both spontaneous and elicited locomotor function in ccd-5 and nid-1 ccd-5 animals in an effort to assess the functional impacts of these mutations. We compared these lines with nid-1 and ccd-5 single mutants, as well as GFP tagged parental lines as negative controls. As a positive control, we analyzed lin-11 null mutants in which AVG fails to differentiate. The lin-11 null mutation results in profound VNC navigation errors and has already been shown to cause motor defects (Hutter 2003), but has not yet been assessed with the nuance offered by the MWT. We assessed behavior in 3 phases: free movement, naive tap response, and habituation.

Movement defects

To assess baseline movement ability of ccd-5 mutants, we recorded free moving worms for 600 s and quantified average forward locomotion speed as well as proportion of time spent in motion vs at rest. Worms typically acclimatize to test set up and return to a baseline locomotion state by the end of a 600-s free roaming period, so we assessed free movement by averaging recorded behavior in three 10 s intervals during 570–600 s post setup. These results are shown in Fig. 11. The parental marker strain performed comparably to WT (data not shown) and no significant differences were observed between ccd-5 or nid-1 single mutants or the ccd-5 nid-1 double mutant and the marker strain. In contrast, lin-11 mutants moved less frequently and more slowly than all other single mutants. The movement defects in lin-11 mutants, where AVG is absent, provide a reference point for the strongest defects that can be expected.

Fig. 11.

Naive motor response of ccd-5 mutants. Behavior of: marker strain (MS: light gray), nid-1 (dark gray), ccd-5 (light blue), nid-1 ccd-5 (dark blue), and lin-11 (red). a) Average forward movement speed. b) Proportion of animals engaged in forward locomotion at each timepoint, averaged across timepoints. Error bars mark upper limit of 95% confidence interval. *P < 0.05 when compared via ANOVA with the marker strain Pinx-18::GFP.

Naïve tap response defects

Following the initial 600 s of free movement, we administered 30 mechanosensory “tap” stimuli at 10 s intervals and assessed the following variables: response probability, reversal speed, and reversal duration. Naive tap response was assessed by averaging responses to the first 5 tap stimuli. These results are shown in Fig. 12. ccd-5 single mutants performed comparably to the control strains, but nid-1 ccd-5 double mutants were significantly impaired in all measurements. nid-1 single mutants showed decreases in response probability and speed. lin-11 performed at levels significantly below all other lines in reversal speed and response probability, but response duration was not significantly different from the control. These results show that the nid-1 null mutation impairs C. elegans’ ability to respond to a tap challenge with the stereotyped reversal behavior. While the ccd-5 null mutation does not affect this behavior independently, it does exacerbate the effects of the nid-1 null mutation on reversal duration.

Fig. 12.

Response to mechanosensory stimuli in ccd-5 mutants. Behavior of: marker strain (MS: light gray), nid-1 (dark gray), ccd-5 (light blue), nid-1 ccd-5 (dark blue), and lin-11 (red). Plates received 5 consecutive taps in 10 s intervals. Data represent averages of tap response probability (a), average speed of reversal (b), and reversal duration (c). Error bars mark upper limit of 95% confidence interval. *P < 0.05 when compared via ANOVA with the parental marker strain Pinx-18::GFP.

Habituation defects

Habituation is a form of simple learning in which response likelihood and/or magnitude decreases as a result of repeated stimulation. The underlying circuit of tap habituation has been mapped out through laser ablation studies (Wicks and Rankin 1995). As mentioned above, we delivered 30 taps at 10 s intervals, and used the first 5 to assess naive tap response. We measured habituation by assessing responses to all 30 taps qualitatively (Fig. 13, right), as well as quantifying the % difference between responses to the first and last taps (Fig. 13, left).

Fig. 13.

Habituation in ccd-5 mutants. Habituation of: marker strain (MS: light gray), nid-1 (dark gray), ccd-5 (light blue), nid-1; ccd-5 (dark blue), and lin-11 (red). Thirty taps were administered in 10 s intervals to induce habituation to mechanosensory stimuli. Shown here are probability of response (a), speed of reversal (b), reversal duration (c). Left: moving 3-tap average of responses from each tap. Right: bar graphs show the percent change from the first response to the averaged last 3 responses. Error bars mark upper limit of 95% confidence interval. Significance *P < 0.05 compared via ANOVA with parental marker strain Pinx-18::GFP.

As in baseline movement and naive response to taps, ccd-5 single mutants showed no defects in any measurement of habituation, and their response curves are consistently indistinguishable from the control. In stark contrast, lin-11 mutants perform reliably below the positive control and produce noticeably flatter response curves. Results for nid-1 ccd-5 habituation were inconsistent, with these mutants correctly responding less frequently to taps over time and for shorter durations, but without decreasing their reversal speed. This effect is seen to a lesser extent in nid-1 single mutants. Overall, nid-1 ccd-5 mutants demonstrate mild deficits in habituation.

Discussion

CCD-5 is a novel AVG axon guidance regulatory factor

We have identified ccd-5 as an important regulator of axon guidance in C. elegans. ccd-5 is a homolog of mammalian C2CD5, also known as KIAA0528 or CDP138. In cultured human breast cancer cells, C2CD5 physically interacts with Cdk5 and FIBP, facilitating cell proliferation and migration (Xu et al. 2014). C2CD5 interacts with Cdk5 to regulate lipid droplet transport in COS-1 cells (Chapman et al. 2019). C2CD5 has also been shown to interact with the endocytosis machinery in the rat hypothalamus, and is expressed widely throughout the mammalian brain (Gavini et al. 2020), though little is known about C2CD5 activity in the mammalian brain. Outside the brain, C2CD5 is expressed in sympathetic nerve terminals of the adrenal medulla in mice, where it regulates catecholamine secretion (Zhou et al. 2018).

Both CCD-5 and C2CD5 proteins have a single C2 calcium dependent phospholipid-binding domain at the N-terminus, suggesting activity-dependent membrane interaction and a possible role in membrane localization. The C-terminal region of C2CD5 is required for Cdk5 and FIBP binding (Xu et al. 2014). The original mutation we identified in our screens, ccd-5(hd152), is a point mutation in the 9th intron of ccd-5. A second mutation ccd-5(gk700962) is a point mutation 27 base pairs upstream of ccd-5(hd152) in the same intron. Both alleles cause a similar phenotype, and these alleles failed to complement each other, confirming that this region plays a role in AVG axon guidance. The effects of these 2 mutations on ccd-5 function are currently unclear; they do not seem to affect transcript level. To confirm that ccd-5 function is required for AVG axon navigation, we generated 2 deletion alleles using a CRISPR/Cas9 strategy. The first allele, ccd-5(gk5256), deletes exons 1–12 (out of 14 exons) and is expected to be a complete loss-of-function allele. The second allele, ccd-5(gk5976), deletes exons 1–8 but leaves intact intron 9, the region affected by ccd-5(gk700962) and ccd-5(hd152). All 4 alleles show similar phenotypes, suggesting that they are strong loss-of-function alleles of ccd-5.

CCD-5 may affect axon guidance through regulation of vesicle exocytosis

We found that ccd-5 and cdk-5 are both required to prevent AVG midline crossing in a nid-1 null background, suggesting that these genes share a pathway. CDK-5 and its homologs have been implicated in a wide variety of processes that could potentially affect AVG axon guidance. For instance, CDK-5 was shown to regulate polarized trafficking of neuropeptide containing dense core vesicles in C. elegans motoneurons in an unc-104/KIF1A independent manner (Goodwin et al. 2012). cdk-5 is also associated with unc-6/netrin mediated microtubule reorganization and GLR-1 receptor trafficking (Dhavan and Tsai 2001; Juo et al. 2007). In C. elegans, unc-6 is expressed by ventral epidermal cells during the outgrowth of VNC pioneer axons (Wadsworth et al. 1996).

In mammals, Cdk5 regulates synaptic vesicle docking through phosphorylation of Munc18 (Bhaskar et al. 2004). We have previously identified AEX-3 as affecting AVG axon guidance through RAB-3 associated vesicles and found that these factors genetically interact with UNC-5, the UNC-6/netrin receptor (Bhat and Hutter 2016). Here, we establish that CCD-5, CDK-5, and UNC-18 genetically act in this pathway as well.

In Fig. 14, we describe a model for how all genes included in this discussion could collaborate to guide AVG. In this model, CCD-5 facilitates CDK-5 phosphorylation of UNC-18 at docked RAB-3 and/or IDA-1 associated vesicles. This causes the SNARE complex to dissociate, resulting in vesicle exocytosis and the incorporation of UNC-5 into the membrane of the extending growth cone. This model is the simplest explanation that incorporates all implicated genes. However, it is possible that ccd-5 and cdk-5 affect AVG axon guidance in a manner that is less directly upstream of unc-18. Further studies are needed to assess this possibility.

Fig. 14.

Schematic of the genetic pathway regulating AVG navigation. The figure describes the observed genetic interactions from the current study and our previous study (Bhat and Hutter 2016) in the context of the known molecular functions of the proteins. Proteins from the current publication contributing to this larger picture are bolded.

CCD-5 is needed for correct pioneering of the VNC in the absence of nidogen

When AVG is ablated before it can extend its axon into the right VNC, the VNC often becomes disorganized (Durbin 1987; Hutter 2003). In lin-11 mutants, where AVG fails to differentiate, the VNC disorganization is even more pronounced. In ast-4/col-99, ast-6/epi-1, and unc-130/FOXD4 mutants, CI and motoneurons extend within the left VNC with AVG (Hutter et al. 2005). These authors observed that when AVG crossed into the left VNC, it could be joined by a subset of CI axons, or all CI axons. In unc-130 mutants, AVG was only ever joined in the left VNC by a subset of CI axons. In epi-1 mutants, AVG was joined by all CI (as opposed to only some) 55% of the time. In col-99 mutants, this occurs in 84% of incidences where CI and AVG meet in the left VNC. The variability with which some or all of CI join AVG in the left VNC in these mutants’ hints at a variety of underlying causes for the observed CI defects.

We observed a variety of AVG axon guidance defects as well as CI and MN axon defects in nid-1 ccd-5 double mutants. The most pronounced defect we observed was that of axons crossing the midline, so this is the phenotype we chose to focus on. We observed that, in a nid-1 null background, the ccd-5 associated increase in CI midline crossing defects can be exclusively attributed to these axons following AVG across the midline while fully fasciculated. This indicates that increased CI axon guidance defects caused by the ccd-5 null allele are dependent on AVG defects: as the rate of AVG crossovers increase, they mislead fasciculated CI axons that would not have crossed the midline had they not been following AVG. This is also true for fasciculated bundles of DD/VD motoneuron axons; increases in DD/VD axons crossing the midline as a single fascicle were only observed when also fasciculated with AVG. We also observed an increase in individual or subsets of DD/VD axons crossing the midline in nid-1 ccd-5 independent of AVG, suggesting a more direct role for ccd-5 in DD/VD axon guidance specifically.

We hypothesize that ccd-5 is required to prevent midline crossovers in AVG and DD/VD axons, and may also play a role in maintaining DD/VD fasciculation. On top of this more direct role of ccd-5 on axon guidance, both DD/VD and CI axons will follow a misguided AVG axon across the midline when they are closely fasciculated. This finding reinforces the important role of AVG in pioneering the right VNC and establishes a novel assay for assessing the role of fasciculation in axon guidance.

Impact of ccd-5 on motor function is subtle

The VNC in C. elegans contains interneuron and motoneuron axons that regulate movement. Given the high penetrance of axon navigation defects seen in nid-1 ccd-5 double mutants when compared with the nid-1 and ccd-5 single mutants, we would expect to see motor defects in the double mutant line that are absent or substantially more subtle in the associated single mutants. We see this in the context of habituation, but locomotion overall seems more affected by nid-1 than ccd-5. These results were also subtle and inconsistent across parameters. The minor movement and behavioral defects in nid-1 ccd-5 double mutants implies that the substantial VNC navigation defects described here have relatively little functional impact. This might be the direct result of the pioneer–follower relationship discussed above, where follower axons are able to remain fasciculated even as the AVG axon is misguided in the absence of NID-1 and CCD-5. The sustained fasciculation of axons that form synapses en passant, could allow the motor circuit to form and function largely unimpeded regardless of which side of the midline the axons are located. Alternatively, the motor circuit might tolerate a certain amount of disruption, at least under laboratory conditions.

Conclusion

ccd-5 is a novel gene regulating AVG axon guidance, which codes for a putative CDK-5 binding partner. Through genetic analysis in a sensitized nid-1 null background, we found that ccd-5 and cdk-5 affect AVG axon guidance in cooperation with unc-18 through a previously described rab-3 associated vesicle transport pathway. This pathway includes unc-5, the unc-6/Netrin receptor.

Here, we show that nid-1 ccd-5 double mutants have significantly increased incidence of pioneer and follower axon navigation defects. Follower axon defects frequently coincide with those of the pioneer (AVG), supporting the hypothesis that follower axon defects are mainly the result of these axons following a misguided pioneer. Despite substantial axon guidance defects of axons in the motor circuit, we observed only subtle movement or behavioral defects. These results emphasize the importance of the pioneer–follower relationship and may suggest some flexibility in the functioning of a neuronal circuit in the absence of a completely correct wiring pattern.

Data availability

Strains and plasmids are available upon request. The authors affirm that all data necessary for confirming the conclusions of the article are present within the article, figures, and tables.

The raw sequence data from this study have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA; ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra) under accession number PRJNA781272.

Acknowledgments

Some strains were provided by the CGC, which is funded by NIH Office of Research Infrastructure Programs (P40 OD010440).

Funding

This work was supported by the National Sciences and Engineering Research Council grant RGPIN-2017-03942 (awarded to HH) and the Canadian Institute of Health Research grant PJT-148549 (awarded to DGM).

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Literature cited

- Au V, Li-Leger E, Raymant G, Flibotte S, Chen G, Martin K, Fernando L, Doell C, Rosell FI, Wang S, et al. CRISPR/Cas9 methodology for the generation of knockout deletions in Caenorhabditis elegans. G3 (Bethesda). 2019;9(1):135–144. doi:10.1534/g3.118.200778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhaskar K, Shareef MM, Sharma VM, Shetty APK, Ramamohan Y, Pant HC, Raju TR, Shetty KT.. Co-purification and localization of Munc18-1 (p67) and Cdk5 with neuronal cytoskeletal proteins. Neurochem Int. 2004;44(1):35–44. doi:10.1016/S0197-0186(03)00099-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat JM, Hutter H.. Pioneer axon navigation is controlled by AEX-3, a guanine nucleotide exchange factor for RAB-3 in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 2016;203(3):1235–1247. doi:10.1534/genetics.115.186064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner S. The Genetics of Caenorhabditis Elegans. Genetics. 1974;77(1):71–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao J, Packer JS, Ramani V, Cusanovich DA, Huynh C, Daza R, Qiu X, Lee C, Furlan SN, Steemers FJ, et al. Comprehensive single-cell transcriptional profiling of a multicellular organism. Science. 2017;357(6352):661–667. doi: 10.1126/science.aam8940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman DE, Reddy BJN, Huy B, Bovyn MJ, Cruz SJS, Al-Shammari ZM, Han H, Wang W, Smith DS, Gross SP, et al. Regulation of in vivo dynein force production by CDK5 and 14-3-3ε and KIAA0528. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):228. doi:10.1038/s41467-018–08110-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chitnis AB, Kuwada JY.. Elimination of a brain tract increases errors in pathfinding by follower growth cones in the zebrafish embryo. Neuron. 1991;7(2):277–285. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90266-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis MW, Hammarlund M, Harrach T, Hullett P, Olsen S, Jorgensen EM.. Rapid single nucleotide polymorphism mapping in C. elegans. BMC Genomics. 2005;6:118.doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-6-118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhavan R, Tsai L-H.. A decade of CDK5. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2(10):749–759. doi: 10.1038/35096019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durbin RM. Studies on the development and organisation of the nervous system of Caenorhabditis elegans. 1987.

- Gavini CK, Cook TM, Rademacher DJ, Mansuy-Aubert V.. Hypothalamic C2-domain protein involved in MC4R trafficking and control of energy balance. Metabolism. 2020;102:153990.doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2019.153990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin PR, Sasaki JM, Juo P.. Cyclin-dependent kinase 5 regulates the polarized trafficking of neuropeptide-containing dense-core vesicles in Caenorhabditis elegans motor neurons. J Neurosci. 2012;32(24):8158–8172. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0251-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham ME, Prescott GR, Johnson JR, Jones M, Walmesley A, Haynes LP, Morgan A, Burgoyne RD, Barclay JW.. Structure-function study of mammalian Munc18-1 and C. elegans UNC-18 implicates domain 3b in the regulation of exocytosis. PLoS One. 2011;6(3):e17999.doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedgecock EM, Culotti JG, Hall DH.. The unc-5, unc-6, and unc-40 genes guide circumferential migrations of pioneer axons and mesodermal cells on the epidermis in C. elegans. Neuron. 1990;4(1):61–85. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90444-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutter H. Extracellular cues and pioneers act together to guide axons in the ventral cord of C. elegans. Development. 2003;130(22):5307–5318. doi: 10.1242/dev.00727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutter H, Wacker I, Schmid C, Hedgecock EM.. Novel genes controlling ventral cord asymmetry and navigation of pioneer axons in C. elegans. Dev Biol. 2005;284(1):260–272. doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki K, Staunton J, Saifee O, Nonet M, Thomas JH.. aex-3 encodes a novel regulator of presynaptic activity in C. elegans. Neuron. 1997;18(4):613–622. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80302-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juo P, Harbaugh T, Garriga G, Kaplan JM.. CDK-5 regulates the abundance of GLR-1 glutamate receptors in the ventral cord of Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18(10):3883–3893. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e06-09-0818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Wadsworth WG.. Positioning of longitudinal nerves in C. elegans by Nidogen. Science. 2000;288(5463):150–154. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5463.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klose M, Bentley D.. Transient pioneer neurons are essential for formation of an embryonic peripheral nerve. Science. 1989;245(4921):982–984. doi: 10.1126/science.2772651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N, Marth G, Abecasis G, Durbin R; 1000 Genome Project Data Processing Subgroup. The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(16):2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rash BG, Richards LJ.. A role for cingulate pioneering axons in the development of the corpus callosum. J Comp Neurol. 2001;434(2):147–157. doi: 10.1002/cne.1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swierczek NA, Giles AC, Rankin CH, Kerr RA.. High-throughput behavioral analysis in C. elegans. Nat Methods. 2011;8(7):592–598. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson O, Edgley M, Strasbourger P, Flibotte S, Ewing B, Adair R, Au V, Chaudhry I, Fernando L, Hutter H, et al. The million mutation project: a new approach to genetics in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genome Res. 2013;23(10):1749–1762. doi:10.1101/gr.157651.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Stetina SE. The motor system. In: The Neurobiology of C. elegans. Elsevier, 2006. p. 125–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wadsworth WG. Moving around in a worm: netrin UNC-6 and circumferential axon guidance in C. elegans. Trends Neurosci. 2002;25(8):423–429. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(02)02206-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wadsworth WG, Bhatt H, Hedgecock EM.. Neuroglia and pioneer neurons express UNC-6 to provide global and local netrin cues for guiding migrations in C. elegans. Neuron. 1996;16(1):35–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White JG, Southgate E, Thomson JN, Brenner S.. The structure of the nervous system of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1986;314(1165):1–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wicks SR, Rankin CH.. Integration of mechanosensory stimuli in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Neurosci. 1995;15(3):2434–2444. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-03-02434.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu S, Li X, Gong Z, Wang W, Li Y, Nair BC, Piao H, Yang K, Wu G, Chen J, et al. Proteomic analysis of the human cyclin-dependent kinase family reveals a novel CDK5 complex involved in cell growth and migration. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2014;13(11):2986–3000. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M113.036699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D, Aravind L.. Identification of novel families and classification of the C2 domain superfamily elucidate the origin and evolution of membrane targeting activities in eukaryotes. Gene. 2010;469(1–2):18–30. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2010.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou QL, Song Y, Huang C-H, Huang J-Y, Gong Z, et al. Membrane trafficking protein CDP138 regulates fat browning and insulin sensitivity through controlling catecholamine release. Mol Cell Biol. 2018;38. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00153-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Strains and plasmids are available upon request. The authors affirm that all data necessary for confirming the conclusions of the article are present within the article, figures, and tables.

The raw sequence data from this study have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA; ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra) under accession number PRJNA781272.