-

A

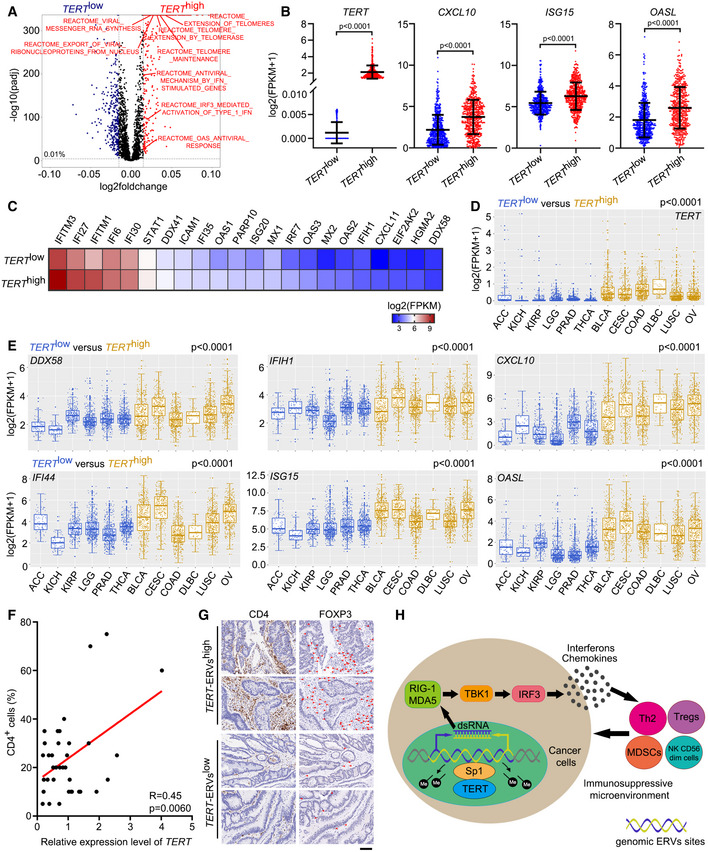

Scatterplot representing differences in ssGSEA of cellular pathways in TERT

high versus TERT

low tumours (n = 4,632 tumours in each group) across TCGA.

-

B

TCGA fragments per kilobase million (FPKM) values of TERT, CXCL10, ISG15, and OASL in tumours grouped in TERT

high (n = 500) and TERT

low (n = 500) groups. Data represent mean ± SD. P‐values were analysed using unpaired two‐tailed Student’s t‐tests.

-

C

TCGA FPKM values of interferon‐related genes in tumours grouped in TERT

high (n = 500) and TERT

low (n = 500) groups. Heat map showing mean FPKM values of each gene.

-

D, E

Expression of TERT (D) and DDX58, IFIH1, CXCL10, IFI44, ISG15, and OASL (E) in TERT

high and TERT

low cancer types (6 types in each). ACC (adrenocortical carcinoma), n = 79. KICH (kidney chromophobe), n = 66. KIRP (kidney renal papillary cell carcinoma), n = 291. LGG (brain lower grade glioma), n = 532. PRAD, n = 502. THCA, n = 513. BLCA (bladder urothelial carcinoma), n = 414. CESC (cervical squamous cell carcinoma and endocervical adenocarcinoma), n = 306. DLBC (lymphoid neoplasm diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma), n = 48. LUSC (lung squamous cell carcinoma), n = 502. OV (ovarian serous cystadenocarcinoma), n = 430. All boxplots include the median line, box indicates the interquartile range (IQR) and whiskers denote the 1.5 × IQR. P‐values were analysed using two‐tailed Mann–Whitney U test.

-

F

Regression analysis of the correlation between TERT expression and percentage of CD4+ cells in colon tumours. n = 36.

-

G

Representative sections of immunohistochemical staining of CD4 and FOXP3 in TERT‐ERVshigh and TERT‐ERVslow colon tumours. Red arrowheads indicate FOXP3+ cells. Scale bar = 100 μm.

-

H

Schematic model showing TERT contributing to immunosuppressive tumour microenvironment by activating ERVs.