Abstract

The comparison of growth, whether it is between different strains or under different growth conditions, is a classic microbiological technique that can provide genetic, epigenetic, cell biological, and chemical biological information depending on how the assay is used. When employing solid growth media, this technique is limited by being largely qualitative and low throughput. Collecting data in the form of growth curves, especially automated data collection in multi-well plates, circumvents these issues. However, the growth curves themselves are subject to stochastic variation in several variables, most notably the length of the lag phase, the doubling rate, and the maximum expansion of the culture. Thus, growth curves are indicative of trends but cannot always be conveniently averaged and statistically compared. Here, we summarize a simple method to compile growth curve data into a quantitative format that is amenable to statistical comparisons and easy to graph and display.

Keywords: growth curve, microbe, Saccharomyces cerevisiae

INTRODUCTION

The study of microbes has a long and storied history, going at least as far back as van Leeuwenhoek’s observation of “animalcules” (what we now know are yeast cells) when examining fermenting beer under his microscope.[1] Since that time, microbiology has impacted our understanding of the basic processes of life, health, and medicine, as well as led to technological and biotechnological advancements. Indeed, the study of microbes remains a rich and active area of research. Contemporary work addresses everything from cell-cell communication[2] to evolution[3] to DNA repair,[4] and still involves the study of fermented beverages[5] that van Leeuwenhoek started.

Despite the various experimental techniques and approaches being developed to reflect the broad scope of microbiological research, one commonly used basic method across sub-disciplines is the comparison of growth between different species, different strains, or different culture conditions. Classic examples of this are live-dead assays or blue-white screening,[6] which provide striking and easily interpretable visual data. However, biological results are rarely binary, and even blue-white screening often yields colonies with a range of blue intensities.

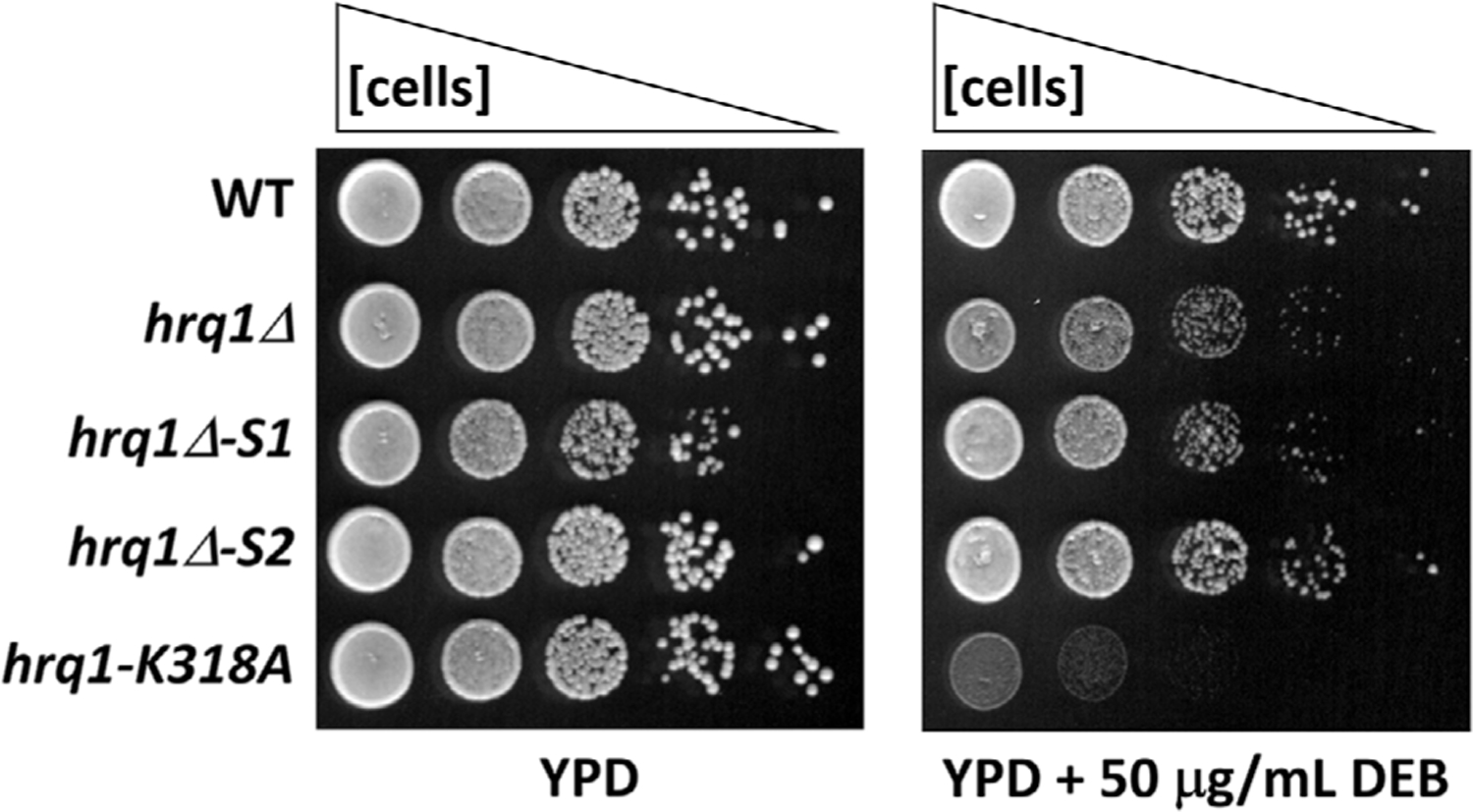

In the face of such intermediate phenotypes, cell spotting of serial dilution—what we refer to as spot dilution assays—are often more useful. For instance, the spot dilution assay in Figure 1 shows the variable sensitivity of wild-type and mutant Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains to the DNA inter-strand crosslinking agent diepoxybutane (DEB).[7] Compared with wild-type, the hrq1-k318A cells are most sensitive to DEB, while the other mutants display intermediate levels of sensitivity. However, as above, there are problems with these types of assays, chief of which is that they are qualitative or semi-quantitative at best. Additionally, very subtle growth phenotypes can be missed if the plates are imaged after being allowed to incubate too long. Reiteratively imaging plates over time and using software to compare the change in colony size to wild-type or another control can address some of this (e.g., the calculation of mutant fitness in synthetic genetic array [SGA]) analyses[8]), but it is cumbersome, time consuming, and difficult to perform with spot dilution assays relative to SGA analyses.

FIGURE 1.

Spot dilution assay of S. cerevisiae DEB sensitivity. Cells of the indicated genotypes (see[11]) were grown to saturation in rich medium (YPD), diluted to an optical density at 600 nm of 1.0, serially diluted 10-fold to 10−4, and then 5 μL of each dilution was spotted onto YPD plates and YPD plates containing DEB. The plates were incubated at 30°C for ~36 h before imaging using a flatbed scanner. The hrq1Δ-S1 and -S2 genotypes refer to random mutations that occurred in the parental hrq1Δ strain

For many, the solution to these problems is simply to use another classic microbiological technique—monitoring liquid culture growth over time and plotting growth curves. Further, with the development of multi-well plates and shaking/incubating plate readers, this process can be high-throughput and automated. In our laboratory, we routinely monitor the growth of 200-μL S. cerevisiae liquid cultures in 96-well plates, automatically measuring the OD at 660 nm (OD660) every 15 min for 24 or 48 h, providing nearly 100 or 200 data points (respectively) for multiple strains and/or growth conditions in parallel. Unfortunately, growth curve datasets are not without their drawbacks as well. Herein, we detail the problems associated with plotting and comparing growth curve data and describe a simple solution that has truly enabled us to quantitatively compare apples to oranges.

THE PROBLEMS WITH GROWTH CURVES

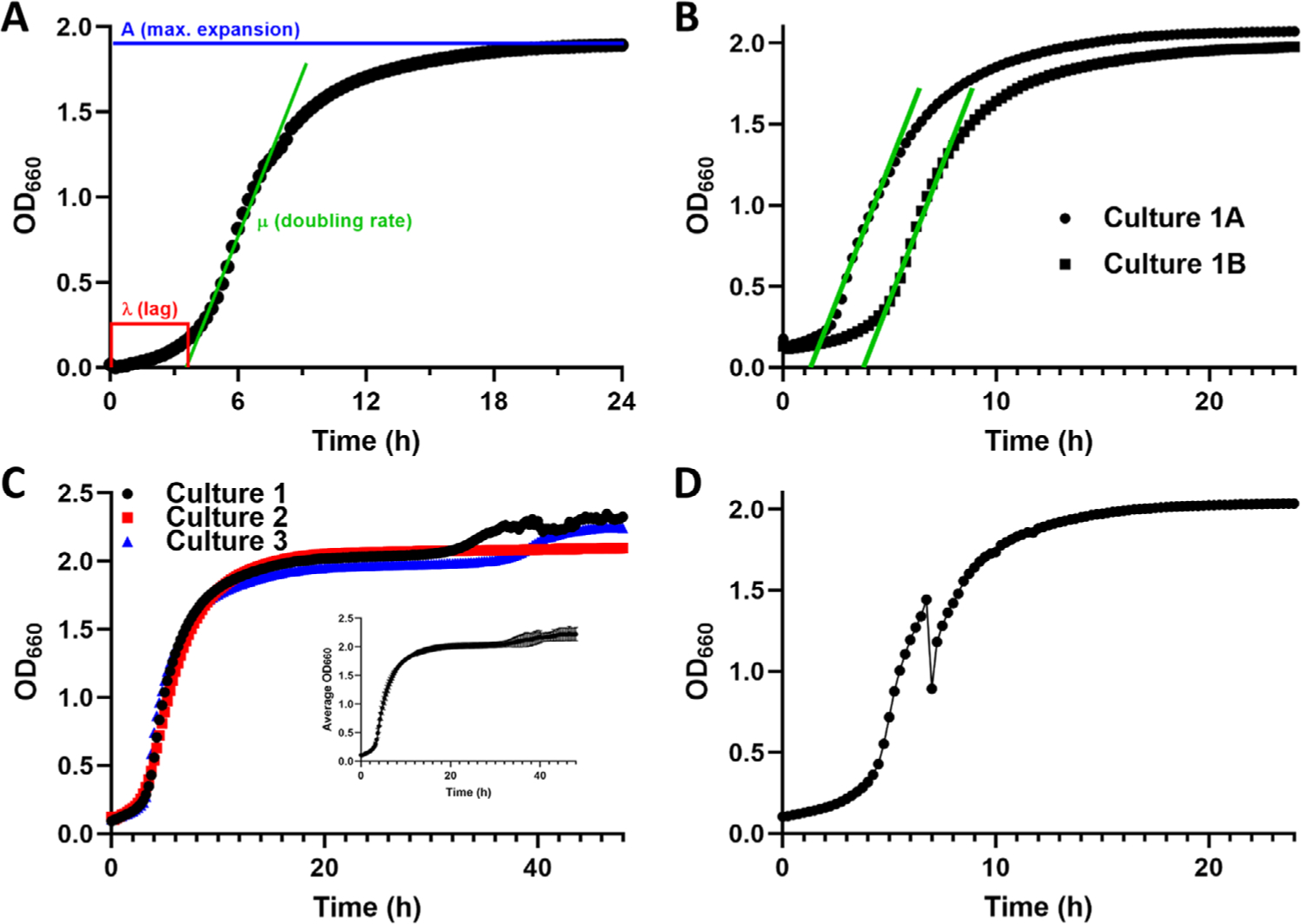

As described previously, three key features of a growth curve can describe the kinetics of microbial growth: (1) λ, the lag time that the cultures takes to recover from back-dilution, media shock, and/or other shifting environmental conditions to achieve exponential growth; (2) μ, the doubling rate of the culture, that is, the slope of the linear portion of the exponential growth phase; and (3) A, the terminal culture density or maximum expansion achieved by the cells over the course of the growth curve (Figure 2A).[9] However, each of these parameters can vary stochastically between biological or even technical replicates of a single strain, making it difficult to average data across experiments and to perform statistical comparisons. For instance, Figure 2B shows growth curves of two cultures of the same strain with similar μ and A values but different λ. Similarly, Figure 2C displays three growth curves with nearly identical λ and μ, but variable A. The inset demonstrates how averaging such data yields large standard deviation values for the last 25% of the data. Monitoring microbial growth in plate readers is also subject to problems such as gas bubbles interfering with OD measurements (e.g., the break in the growth curve in Figure 2D). Finally, it should also be noted that the state of the starting cultures used to back-dilute into fresh medium also affects growth kinetics. A liquid culture grown to stationary phase will display a longer λ than a culture grown to log phase when back-diluted. This type of error is common between biological replicates if starter culture growth conditions are not strictly controlled, as well as among strains that have different growth rates.

FIGURE 2.

Problems with growth curves. (A) An example of 24-h growth curve with data taken at 15-min intervals and indicating the three major variables describing the growth kinetics of microbes: λ, the length of time the cells are in lag phase; μ, the doubling rate; and A, the maximum expansion achieved by the culture. This image is adapted from[9]. (B) An example of two independent cultures of the same S. cerevisiae strain displaying nearly identical doubling rates but variation in both λ and A. (C) An example of three replicates of growth curve data for a single S. cerevisiae strain displaying similar λ and μ but varied A. The inset shows that averaging the data and plotting the mean and standard deviation yields a curve marred by wide error bars (standard deviation) at the end of the growth period. (D) A growth curve showing a “break” in the cell density at mid-log phase, presumably due to an air bubble interfering with the OD660 measurements

WHAT ARE THE SOLUTIONS?

There are various ways to deal with such issues. For instance, some authors simply show representative curves of single cultures rather than attempt to average data (see Figure 1 in[10]). Others display averaged data from three or more experiments but omit error bars (see Figure 2B in[11]). In some cases, a large number (> > 3) of individual experiments are performed and used to calculate means and perform statistical comparisons, but this approach limits the high-throughput advantage of such plate reader assays. Finally, random problems such as bubbles occluding optics can be avoided by assaying technical replicates of individual cultures and omitting curves with obvious problems from subsequent analyses, but this again decreases the throughput of the assay.

More recently, Ngo and colleagues have reported success in identifying small molecule inhibitors of DNA replication in high-throughput assays by combining the analysis of growth curves with linear discriminant analysis.[9] This method takes into account λ, μ, and A from treated and untreated cells and calculates Zʹ factors using all three parameters rather than one or more individually, as previously described.[12] This method extended their range of detectable replication inhibition to drug concentrations that otherwise yielded non-significant Zʹ factors when Zʹ was calculated for single parameters.

OUR METHOD

Our laboratory studies the roles of DNA helicases in maintaining genome integrity. We are currently interested in determining why over-expression of the Pif1 helicase in S. cerevisiae is toxic to cells,[13] and we performed a variety of in vivo and in vitro analyses to investigate this phenomenon. To date, we have found that Pif1 is acetylated on one or more lysine residues, and the acetylation status of Pif1 affects toxicity upon over-expression as judged by cell growth with and without helicase over-expression and in wild-type, acetyltransferase mutant, and deacetylase mutant genetic backgrounds.[14,15]

The above work entailed the comparison of growth among dozens of different strains and culturing conditions, and we sought to analyze and present the data in a quantitative manner. We were inspired by the work of Andis et al. but wanted to avoid the need to perform the mathematically complex linear discriminant analyses[9] to rapidly generate easily interpretable data. We reasoned that taking into account λ, μ, and A together from each growth curve was most important way to do this. Thus, we simply measured the OD660 every 15 min for 48 h for each culture and averaged the OD660 values across the entire growth curve to generate a single value representing the growth of each culture.[15] Because we were interested in the effects of Pif1 over-expression, we normalized to data from a strain of the same genetic background but carrying an empty vector. Thus, the read out in the end was independent of the growth kinetics of individual wild-type or mutant background, as well as changes in culturing parameters such as incubation temperature, and we could evaluate only the effect of helicase over-expression. Such experiments yielded repeatable, quantitate results that could be averaged and used for statistical comparisons, showing that Pif1 over-expression causes a > 2-fold decrease in cell growth that can be rescued by mutation of the acetyltransferase Esa1 or exacerbated ~two-fold by the mutation of the Rpd3 or Hda2 deacetylases (all P < 0.001; see Figure 1 in[14]). The same method was used to demonstrate the contribution of the N-terminal domain of Pif1 to toxicity (e.g., comparing overexpression of Pif1 and Pif1ΔN in vivo), and we have extended these analyses to chemogenomics to determine the effects of DNA damaging compounds during Pif1 over-expression (Sausen and Bochman, unpublished). Due to its versatility, this method has quickly become the default way in which we present data from growth curves.

THE METHOD IN ACTION

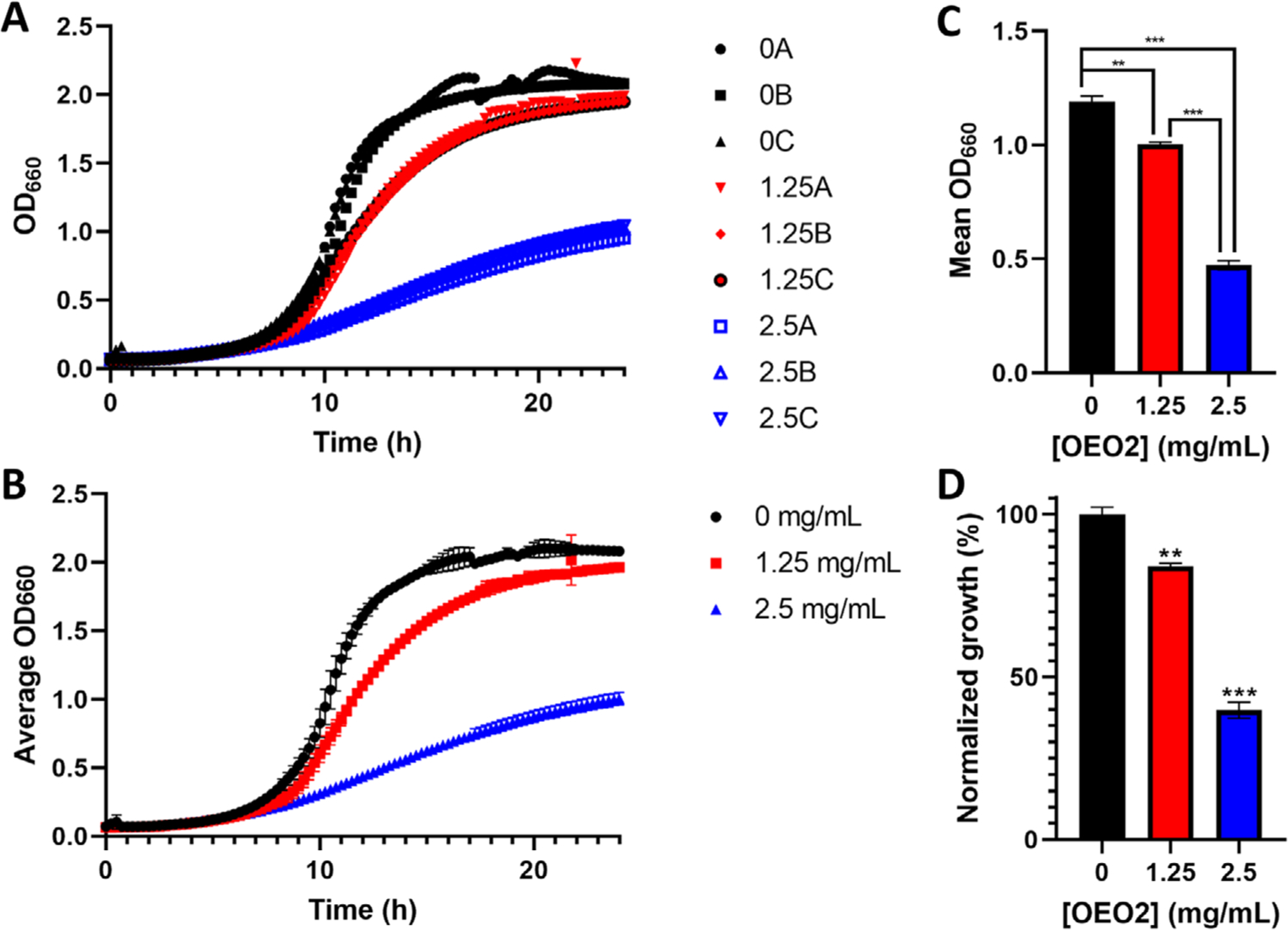

To demonstrate the convenience of our method to quantify microbial growth, we show the four common data processing steps in Figure 3. Here, we start with triplicate growth curves of wild-type S. cerevisiae grown in the absence or presence of 1.25 or 2.5 mg/mL OEO2 (Figure 3A), an analog of 3,4-epoxybutane-1,2-diol, which is a metabolite of the human carcinogen 1,3-butadiene[16]. Unsurprisingly, with all nine individual growth curves plotted on the same graph, the individual data points are hard to discern from one another. In Figure 3B, the averages and standard deviations of the three datasets are plotted, which simplifies analysis and interpretation (i.e., OEO2 treatment displays dose-dependent toxicity) but is not quantitative. To achieve that, Figure 3C shows the mean of the OD660 across each growth curve from Figure 3B, yielding a single data point for each treatment that can be displayed as a simple bar graph. Finally, Figure 3D normalizes the data in Figure 3C to growth in the absence of OEO2, providing a readily interpretable plot showing that 1.25 mg/mL and 2.5 mg/mL OEO2 significantly decrease growth by 16 ± 1% (P = 0.0003) and 60 ± 2% (P = 6 × 10−6) relative to untreated cells, respectively. Overall, this method is a rapid, efficient, and quantitative way to display microbial growth data. To aid in the implementation of this method for those unfamiliar with the process, we have diagrammed and explained the broad strokes in Box 1.

FIGURE 3.

Step-by-step data analysis with our method. (A) Three growth curves (A, B, and C) each for wild-type cells grown in rich medium (black, 0) or rich medium supplemented with 1.25 mg/mL (red, 1.25) or 2.5 mg/mL (blue, 2.5) OEO2[]. (B) The data plotted are averages of the triplicate curves shown in (A), and the error bars correspond to standard deviation. (C) To generate the values plotted in the bar graph, the OD660 of each growth curve in (A) was averaged for the entire 24-h growth period with the equation , where t is the time interval used to collect OD660 readings, tend is the last time point, and n is the total number of OD660 readings. In the graphed example, t = 0.25 h, tend = 24 h, and n = 97. Then, the mean of the three growth curve averages for each treatment was calculated. The error bars represent the standard deviation. (D) The data in (C) were normalized to growth in the absence of OEO2 with the equation (M/M0) × 100, where M is a mean value calculated as described above in (C), and M0 is the mean value calculated for cell growth without added OEO2. In (C and D), the data were analyzed using multiple t-tests corrected using the Holm-Sidak method for multiple comparisons in GraphPad Prism. ** P < 0.001 and *** P < 0.0001

Box 1. Step-By-Step Guide to Processing Growth Data.

Initially, the optical density (OD) readings should be arrayed in a spreadsheet. In this example, readings from six time points are shown for three replicates each of a wildtype (WT) and mutant (Mut) strain. Next, the values in the OD columns are averaged across all time points, and then, those values are averaged among all three replicates of each strain. If using Microsoft Excel to perform these manipulations, the ‘ = AVERAGE()’ and ‘ = STDEV()’ commands are convenient ways to quickly determine averages and standard deviations, respectively. In step 4, the data are normalized by dividing each value by, in this case, the WT average. However, this normalization step can be performed as necessary depending on experimental conditions. We have normalized the growth of drug-treated cells to solvent control cells, cell harboring an expression vector to cell containing empty vector, and so on. Finally, the data can be graphed and/or compared using Student’s t-test, for instance, to determine statistical significance.

CONCLUSIONS

As described above, our process to analyze microbial growth retains the simplicity of monitoring and plotting growth curves but takes into account the three kinetic parameters of growth curves[9] to generate quantitative data. Indeed, in some respects, it is even easier to interpret data in our format than via growth curve plots because our data points are normalized and readily display improved or decreased growth as a percentage relative to a standard (e.g., wild-type cells or untreated cells). However, one should still examine the raw growth curves to ensure that the data are not contaminated by an excessive number of outlier points, such as the bubble problem shown in Figure 2D, or dominated by the A value if the growth curves saturate early in a long experiment, such as that shown in Figure 2C. In the former, datasets with many outliers can be excluded from analysis, and in the latter, data from a truncated portion of the time course (20–24 h rather than 48 h) can be analyzed. With many modern plate readers, growth curves are plotted and displayed in real time, so one can quickly scan the data looking for problems without having to plot the curves themselves, simplifying the process even further.

Funding information

National Institute of General Medical Sciences, Grant/Award Number: 1R35GM133437; American Cancer Society, Grant/Award Number: RSG-16–180-01-DMC

Abbreviations:

- DEB

diepoxybutane

- OD660

optical density at 660 nm

- SGA

synthetic genetic array

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1.van Leeuwenhoek A, In: Gale T, van Croonevelt H (Eds.), Delft, 1694,6. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ball AS, & van Kessel JC (2019). The master quorum-sensing regulators LuxR/HapR directly interact with the alpha subunit of RNA polymerase to drive transcription activation in Vibrio harveyi and Vibrio cholerae. Molecular Microbiology, 111, 1317–1334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chaparian RR, Ball AS, & van Kessel JC (2020). Hierarchical transcriptional control of the LuxR quorum-sensing regulon of vibrio harveyi. Journal of Bacteriology, 202(14), e00047–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Samson RY, Obita T, Freund SM, Williams RL, & Bell SD (2008). A role for the ESCRT system in cell division in archaea. Science, 322, 1710–1713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steenwyk JL, Opulente DA, Kominek J, Shen XX, Zhou X, Labella AL, Bradley NP, Eichman BF, Cadez N, Libkind D, DeVirgilio J, Hulfachor AB, Kurtzman CP, Hittinger CT, & Rokas A (2019). Extensive loss of cell-cycle and DNA repair genes in an ancient lineage of bipolar budding yeasts. Plos Biology, 17, e3000255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burby PE, & Simmons LA (2019). A bacterial DNA repair pathway specific to a natural antibiotic. Molecular Microbiology, 111, 338–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bradley NP, Washburn LA, Christov PP, Watanabe CMH, & Eichman BF (2020). Escherichia coli YcaQ is a DNA glycosylase that unhooks DNA interstrand crosslinks. Nucleic Acids Research, 48, 7005–7017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xue M, Kim CS, Healy AR, Wernke KM, Wang Z, Frischling MC, Shine EE, Wang W, Herzon SB, & Crawford JM (2019). Structure elucidation of colibactin and its DNA cross-links. Science, 365, eaax2685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andis NM, Sausen CW, Alladin A, & Bochman ML (2018). The WYL Domain of the PIF1 helicase from the thermophilic bacterium thermotoga elfii is an accessory single-stranded DNA binding module. Biochemistry, 57, 1108–1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Osburn K, Amaral J, Metcalf SR, Nickens DM, Rogers CM, Sausen C, Caputo R, Miller J, Li H, Tennessen JM, & Bochman ML (2018). Primary souring: A novel bacteria-free method for sour beer production. Food Microbiology, 70, 76–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peepall C, Nickens DG, Vinciguerra J, & Bochman ML (2019). An organoleptic survey of meads made with lactic acid-producing yeasts. Food Microbiology, 82, 398–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rogers CM, Veatch D, Covey A, Staton C, & Bochman ML (2016). Terminal acidic shock inhibits sour beer bottle conditioning by Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Food Microbiology, 57, 151–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Messing J, Gronenborn B, Muller-Hill B, & Hopschneider PH (1977). Filamentous coliphage M13 as a cloning vehicle: Insertion of a HindII fragment of the lac regulatory region in M13 replicative form in vitro. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 74, 3642–3646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vieira J, & Messing J (1982). The pUC plasmids, an M13mp7-derived system for insertion mutagenesis and sequencing with synthetic universal primers. Gene, 19, 259–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rogers CM, Simmons Iii RH, Fluhler Thornburg GE, Buehler NJ, & Bochman ML (2020). Fanconi anemia-independent DNA interstrand crosslink repair in eukaryotes. Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology, 158, 33–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baryshnikova A, Costanzo M, Kim Y, Ding H, Koh J, Toufighi K, Youn JY, Ou J, San Luis BJ, Bandyopadhyay S, Hibbs M, Hess D, Gingras AC, Bader GD, Troyanskaya OG, Brown GW, Andrews B, Boone C, & Myers CL (2010). Quantitative analysis of fitness and genetic interactions in yeast on a genome scale. Nature Methods, 7, 1017–1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ngo M, Wechter N, Tsai E, Shun TY, Gough A, Schurdak ME, Schwacha A, & Vogt A (2019). A high-throughput assay for DNA replication inhibitors based upon multivariate analysis of yeast growth kinetics. SLAS Discovery, 24, 669–681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chaparian RR, Tran MLN, Miller Conrad LC, Rusch DB, & van Kessel JC (2020). Global H-NS counter-silencing by LuxR activates quorum sensing gene expression. Nucleic Acids Research, 48, 171–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bochman ML, Paeschke K, Chan A, & Zakian VA, (2014). Hrq1, a homolog of the Human RecQ4 helicase, acts catalytically and structurally to promote genome integrity. Cell reports, 6, 346–356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Durr O, Duval F, Nichols A, Lang P, Brodte A, Heyse S, & Besson D (2007). Robust hit identification by quality assurance and multivariate data analysis of a high-content, cell-based assay. Journal of Biomolecular Screening, 12, 1042–1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kummel A, Gubler H, Gehin P, Beibel M, Gabriel D, & Parker CN (2010). Integration of multiple readouts into the Z’ factor for assay quality assessment. Journal of Biomolecular Screening, 15, 95–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shun T, Gough AH, Sanker S, Hukriede NA, & Vogt A (2017). Exploiting analysis of heterogeneity to increase the information content extracted from fluorescence micrographs of transgenic zebrafish embryos. Assay and Drug Development Technologies, 15, 257–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kozak K, & Csucs G (2010). Kernelized Zâ factor in multiparametric screening technology. RNA Biology, 7, 615–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chang M, Luke B, Kraft C, Li Z, Peter M, Lingner J, & Rothstein R (2009). Telomerase is essential to alleviate Pif1-induced replication stress at telomeres. Genetics, 183, 779–791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nickens DG, Sausen CW, & Bochman ML (2019). Genes (Basel), 10(6), 411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yoshikawa K, Tanaka T, Ida Y, Furusawa C, Hirasawa T, & Shimizu H, (2011). Comprehensive phenotypic analysis of single-gene deletion and overexpression strains of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast, 28, 349–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ononye OE, Sausen CW, Balakrishnan L, & Bochman ML (2020). Lysine acetylation regulates the activity of nuclear Pif1. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 295(46), 15482–15497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ononye OE, Sausen CW, Bochman ML, & Balakrishnan L,Current Genetics, (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nakamura J, Carro S, Gold A, & Zhang Z, (2021). An unexpected butadiene diolepoxide-mediated genotoxicity implies alternative mechanism for 1,3-butadiene carcinogenicity. Chemosphere, 266, 129149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.