Abstract

Progress in the development of salivary gland regenerative strategies is limited by poor maintenance of the secretory function of salivary gland cells (SGCs) in vitro. To reduce the precipitous loss of secretory function, a modified approach to isolate intact acinar cell clusters and intercalated ducts (AIDUCs), rather than commonly used single cell suspension, was investigated. This isolation approach yielded AIDUCs that maintain many of the cell-cell and cell-matrix interactions of intact glands. Encapsulation of AIDUCs in matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-degradable PEG hydrogels promoted self-assembly into salivary gland mimetics (SGm) with acinar-like structure. Expression of Mist1, a transcription factor associated with secretory function, was detectable throughout the in vitro culture period up to 14 days. Immunohistochemistry also confirmed expression of acinar cell markers (NKCC1, PIP and AQP5), duct cell markers (K7 and K5), and myoepithelial cell markers (SMA). Robust carbachol and ATP-stimulated calcium flux was observed within the SGm for up to 14 days after encapsulation, indicating that secretory function is maintained. Though some acinar-to-ductal metaplasia was observed within SGm, it was reduced compared to previous reports. In conclusion, cell-cell interactions maintained within AIDUCs together with the hydrogel microenvironment may be a promising platform for salivary gland regenerative strategies.

Keywords: Salivary gland, MMP-degradable hydrogel, Poly(ethylene glycol), Acinar cells, Cellular plasticity

Introduction

Approximately 50,000 patients in the United States and as many as 500,000 people worldwide are diagnosed annually with head and neck cancers1. Most patients receive standard treatment of radiation therapy or a combination of radiation therapy with chemotherapy2, 3. However, radiation therapy results in atrophy, fibrosis, and degeneration of both major and minor salivary gland tissue, leading to salivary gland hypofunction and xerostomia, which severely affects oral health and quality of life4. There are no regenerative therapies to restore salivary gland function after radiation damage, so patients suffer from life-long xerostomia. Palliative treatments for xerostomia include the use of saliva substitutes and sialagogues to lubricate the mouth, however, these treatments do not fully restore or emulate the myriad functions of the salivary gland5, 6. Thus, development of treatments to provide durable recovery of salivary function are in dire need.

Cell-based therapies are a promising approach to restore salivary gland function. Direct injection of primary mouse submandibular gland (SMG) cells7, 8, c-Kit+ salivary gland cells (SGCs)9–11, or mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs)12–15 into irradiated glands has been shown to partially improve gland function, but restoration of saliva secretion was incomplete and highly variable. Tissue engineering has emerged as a promising strategy to coordinate salivary gland regeneration. Tissue engineering involves the use of a combination of cells, tissue matrix/scaffold and soluble factors that create a 3D microenvironment in which functional constructs assemble and actively interact with the surrounding extracellular matrix (ECM) to restore, maintain, or improve damaged tissues or whole organs. Approaches include use of nanofibers, decellularized extracellular matrix, and hydrogels together with SGCs, growth factors, and other stimuli16–24. Although a few studies have translated their findings in vivo25–27, no study to date has demonstrated complete restoration of gland function.

In our previous research, hydrogels formed via norbornene functionalized PEG macromers crosslinked with MMP degradable peptides were used to encapsulate pre-aggregated SGCs that were derived by culturing single SGCs in tissue culture plates for 2 days in vitro and then cultured for up to 2 weeks in hydrogels22. Adult salivary gland cells have been shown to express multiple MMPs28, 29, which can degrade the peptide crosslinker during cellular assembly. Within MMP-degradable PEG hydrogels, cells organize into structures with apicobasal polarity and increase expression of secretory acinar cell markers (e.g., aquaporin5 (Aqp5)). Although these data are promising, secretory marker expression is still reduced compared to native glands22 and secretory acinar cells begin to express duct markers, including cytokeratins30, likely due to cell dissociation-induced loss of cell-cell and cell-matrix interactions and associated stress induced cellular plasticity30, 31. Indeed, survivability was severely compromised when isolated SGCs were immediately encapsulated within PEG hydrogels (e.g., prior to aggregation), suggesting that cell-cell contacts and cell-material interactions contribute to maintaining cell viability23.

To increase cell viability upon hydrogel encapsulation immediately after isolation and avoid precipitous loss of secretory function during the 2-day aggregate formation, we investigated the isolation of intact acinar cell clusters and intercalated ducts (AIDUCs), an approach which maintains cell-cell contacts during isolation and includes encapsulation. We hypothesized that isolation of AIDUCs versus more rigorous single or multicellular isolation would reduce cell stress and encourage the organization of SGCs into more complex structures that resemble acinar units for use in salivary gland regenerative strategies.

Materials and Methods

Mouse Models:

All experiments were performed on tissue from mice maintained on the C57BL/6J background. Mist1CreERT2 mice were produced as previously described32. R26tdTomato(Gt(ROSA)26Sortm9(CAG-tdTomato)Hze/J) and C57BL/6J mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories. Standard genotyping was performed. Prior to cell isolation, animals were housed on a 12-hour light/dark cycle with ad libitum access to food and water. Genotyping was conducted prior to weaning. All animal protocols were approved and carried out in accordance with the University of Rochester Medical Center’s University Committee on Animal Resources.

Norbornene-functionalized PEG synthesis.

Four-arm 20 kDa PEG was functionalized with norbornene (PEG-Norb) using N,N’-dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (DCC) coupling as previously described33. Briefly, norbornene carboxylate (10 meq per PEG hydroxyl), and DCC (5 meq per PEG hydroxyl) were dissolved in dichloromethane (DCM) at room temperature for 30 min until a white precipitate (dicyclohexylurea) formed, which indicated formation of dinorbornene carboxylic acid anhydride. Four-arm PEG, pyridine (5 meq per PEG hydroxyl) and 4-dimethylaminopyridine (DMAP, 0.5 meq per PEG hydroxyl) was dissolved in DCM and then added dropwise to the anhydride solution, which was subsequently septa sealed, vented with a needle, and stirred overnight at room temperature.

The resulting solution was vacuum filtered and the filtrate was precipitated in chilled diethyl ether, collected by vacuum filtration, re-dissolved in 75 mL DCM, and re-precipitated two additional times in chilled diethyl ether. Structure and percent functionalization (>90%) were determined by 1H-NMR using a Bruker Avance 400MHz spectrometer (1H NMR[CDCL3]: d = 6.0–6.3 [norbornene vinyl protons, 8H, multiplet]), (3.5–3.9 PEG ether protons, 1817H, multiplet). The final product was dialyzed against distilled water (ddH2O) for 3 days using 3500 MWCO dialysis tubing (Spectrum Laboratories) and lyophilized.

Peptide synthesis

The MMP-degradable peptide crosslinker GKKCGPQG↓IWGQCKKG was synthesized by standard solid-phase peptide synthesis on FMOC-Gly-Wang resin (EMD) using a Liberty 1 Microwave-Assisted Peptide Synthesizer (CEM) with UV monitoring, as previously described34. All amino acids (AAPPTec) were dissolved in N-methylpyrrolidone (NMP) at 0.2 M. All amino acids were FMOC-protected, with cysteine and lysine side chains protected with trityl and tertbutyloxycarbonyl, respectively. 0.5 M Benzotriazole-N,N,N’,N’-tetramethyl-uronium-hexafluoro-phosphate (Ana-Spec) in dimethylformamide (DMF) was used as activator, 2 M diisopropropylethylamine (Alfa Aesar) in NMP was used as activator base, and 5% piperazine (Alfa Aesar) in DMF was used for deprotection. Peptides were cleaved and de-protected by adding the on-resin 0.25 mmol peptide (0.316 g resin) to a cleavage cocktail composed of 18.5 mL trifluoroacetic acid (TFA, Acros Organic), 0.5 mL triisopropylsilane (Sigma Aldrich), 0.5 mL ddH2O, and 0.5 mL 3,6 dioxa-1,8-octane dithiol and mixing for 2 h. Cleaved peptide was separated from resin via vacuum filtration, purified via precipitation in ice-cold diethyl ether (~180 mL), and collected by centrifugation. The peptide was resuspended in ice-cold diethyl ether, centrifuged twice more, dried under vacuum overnight, dialyzed against ddH2O using 500 MWCO dialysis tubing (Spectrum Labs) for 48 h, and lyophilized.

Peptide molecular weight was verified using a Bruker AutoflexIII Smartbeam matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometer with 1 mg/mL peptide dissolved in 50:50 acetonitrile: ddH2O + 1% TFA added in a 1:1 volumetric ratio of 10 mg/mL α-Cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid matrix (Tokyo Chemical Industry) dissolved in 50:50 acetonitrile: H2O + 1% TFA. Peptide standards (Bruker Peptide Calibration Standard, 206195) were used for calibration. Peptide purity was analyzed via 205 nm absorbance measured in ddH2O with an Evolution UV/Vis detector (Thermo Scientific) and compared with predicted values using a previously published methodology22, 23.

The photoinitiator LAP was synthesized in a two-step process, as previously described33. Dimethyl phenylphosphonite (Acros Organics) was reacted with 2,4,6-trimethylbenzoyl chloride (Sigma-Aldrich) via a Michaelis-Arbuzov reaction. 3.2 g (0.018 mol) of 2,4,6-trimethylbenzoyl chloride was added dropwise to an equimolar amount of continuously stirred dimethyl phenylphosphonite (3.0 g) at room temperature and under argon. After 18 hours’ reaction, a four-fold excess of lithium bromide (6.1 g) in 100 mL of 2-butanone was added to the reaction mixture and then heated to 50 °C. After 10 minutes, a solid precipitate formed. The mixture was cooled to ambient temperature, allowed to rest for four hours and then filtered. The filtrate was washed and filtered 3 times with 2-butanone to remove unreacted lithium bromide, and vacuum dried overnight.

Isolation and culture of AIDUCs

Primary AIDUCs cells were isolated, as previously described, with minor modifications35, 36. Briefly, female C57BL/6 mice aged 8–12 weeks were euthanized according to animal protocols approved by the University of Rochester University Committee for Animal Resources. SMGs were surgically removed, finely minced with a razor blade, and dissociated by incubation in 10 mL Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) (Gibco) supplemented with 0.5% BSA, 1M CaCl2, 1M MgCl2, 100 U/ml collagenase Type II (Gibco), and 1 mg/mL hyaluronidase (Sigma) at 37 °C for 60 min with gentle shaking. Cells were then passed through 100 μm filters to remove undigested tissues and then 20 μm filters to remove cell debris and red blood cells. The resulting cellular aggregates, sized 20–100 μm, were re-suspended in 5 mL complete media (Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM):F12 [1:1; GIBCO]) supplemented with Glutamine (2 mM, GIBCO), Antibiotic-Antimycotic solution (100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, GIBCO), N2 supplement (0.5×, Invitrogen), 2.6 ng/mL insulin (Life Technologies), 2 nM dexamethasone (Sigma), 20 ng/mL epidermal growth factor (EGF; Life Technologies), and 20 ng/mL basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF; Life Technologies) and cultured at 37 °C.

Three days prior to dissection and AIDUC isolation from female Mist1CreERT2;R26 tdTomato mice, mice were administered tamoxifen (0.25 mg/g body weight) to activate the expression of the tdTomato fluorescent protein in acinar cells. AIDUCs were isolated using the same approach described above.

Hydrogel encapsulation of primary AIDUCs

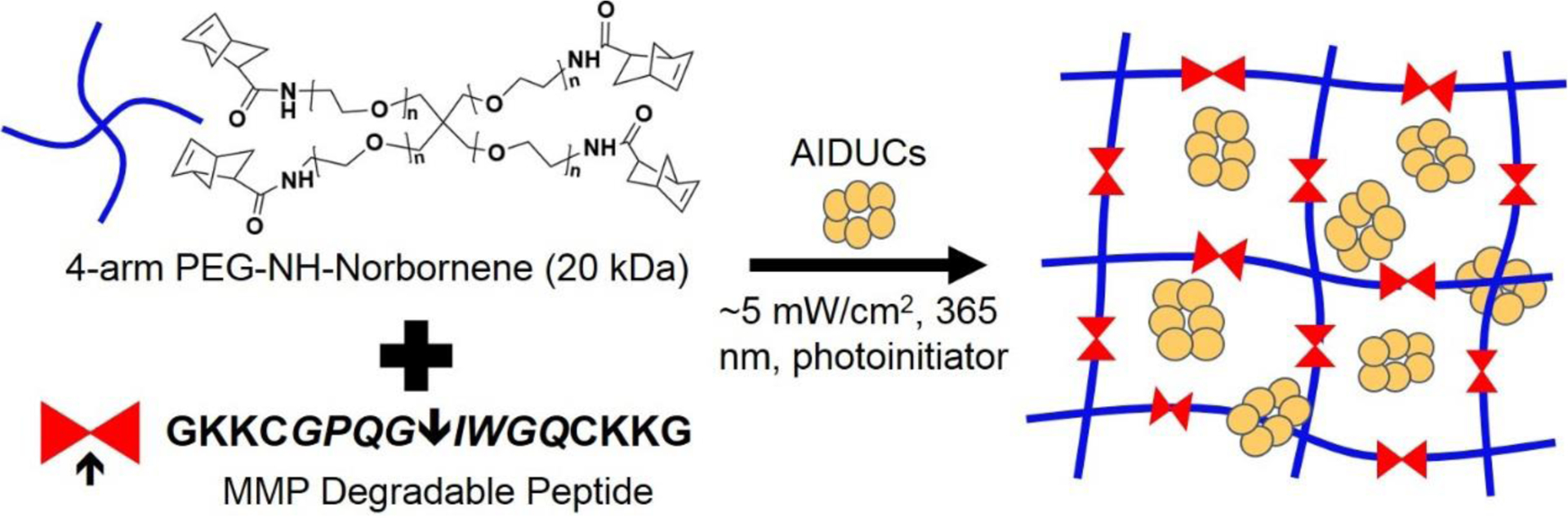

MMP-degradable PEG hydrogels were used to encapsulate AIDUCs (Fig. 1). Hydrogel precursor solutions were made by dissolving lyophilized norbornene-functionalized 4-arm PEG macromer (1.5 mM), MMP-degradable peptide (3 mM), 0.05 wt% of the photoinitiator LAP and 100 μg/ml laminin in PBS. The compressive modulus and swelling ratio of hydrogels were 5.4 ± 0.9 kPa and 2.0 ± 0.1, respectively. The hydrogel precursor solution was then added to freshly-isolated AIDUCs and mixed gently by pipetting until the cells were distributed homogenously in hydrogel suspension. The final cell density in the hydrogel solution was 5×105 cells/mL from which 40 μL of the mixed solution was pipetted into 1 mL syringes with the tips cut off and photopolymerized via exposure to 5 mW/cm2, 365 nm UV light for 5 min. Immediately after polymerization, hydrogels were placed in 24-well plates and incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2. Media was changed daily.

Fig. 1. Schematic representation of hydrogel encapsulation of AIDUCs.

Freshly isolated AIDUCs were mixed with hydrogel precursor solution composed of norbornene-functionalized 4-arm PEG macromer, MMP-degradable peptide and the photoinitiator LAP and 100 μg/ml laminin, and 40 μL of the mixed solution was pipetted into 1 mL syringes with the tips cut off and photopolymerized via exposure to 5 mW/cm2, 365 nm UV light for 5 min to form hydrogels.

Cell viability of hydrogel encapsulated AIDUCs

To evaluate the survivability of encapsulated AIDUCs, the LIVE/DEAD assay (Invitrogen) was utilized according to manufacturer’s instructions with imaging using a Olympus FV1000 laser scanning confocal microscope. Prestoblue (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used to evaluate encapsulated cell metabolic activity to complement LIVE/DEAD imaging. At designated time points, 10% Prestoblue in cell culture media was added to the cell-hydrogel and incubated for 20 min at 37 °C. Metabolic fluorescent conversion was measured with a Biotek plate reader under the excitation wavelength of 560 nm and emission of 590 nm.

Gene expression analysis

To extract RNA from the hydrogels, hydrogels were washed with PBS twice at designated time points and then transferred to 1.5 mL Eppendorf tube filled with ~500 uL 1000 U/ml collagenase II solution. After incubation at 37 °C for ~30 minutes until hydrogels were degraded, the cell pellet was collected via centrifuge at 1500 RPM for 5 min and re-suspended in 1 mL TRIzol (Invitrogen), and stored at −80 °C until RNA extraction. Total RNA was extracted using the OMEGA kit (Omega Bio-Tek). RNA concentration and quality was determined using a Nano-Vue™ UV-Vis spectrophotometer (GE Healthcare).

cDNA was synthesized using the iScriptTM cDNA synthesis kit (BioRad) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Quantitative PCR analysis of individual cDNAs was performed on a CFX96™ Real-Time System (Bio-Rad) using PowerUp SYBR™ Green Master Mix (Bio-Rad) for genes listed in Supplemental Table 1. Quantitative PCR results were normalized to mouse Rps29 mRNA levels and analyzed using the 2−⊿⊿CT method.

Immunohistochemistry staining

After culture for 14 days, hydrogels were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 30 min at room temperature. Hydrogels were then washed 3 times with PBS and embedded in Optimal Cutting Temperature solution (OCT, Tissue-Tek). Then, the hydrogels were cryosectioned using a CM1860 UV cryostat (Leica) into 10 μm sections and mounted on SuperFrost Plus slides (Fisher Scientific). Staining was then performed as previously described22, 36. The primary and secondary antibodies used are listed in Supplemental Table 2. All samples were imaged using a FluoView FV1000 Laser Scanning Confocal Microscope (Olympus).

5-Ethynyl-2’-deoxyuridine (EdU) staining

At designated time points, SGm that formed within hydrogels were treated with 10 μM EdU (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 3 h prior to fixation with 4 % PFA for 30 min, washed twice with DPBS and permeabilized with 0.5 vol% of Triton X-100 for 30min. Samples were washed 2× with 3 wt% BSA in DPBS and labeled with the Click-iT® Plus EdU AlexaFluor® 488 imaging kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and DAPI (Thermo Fisher Scientific) as a nuclear counterstain. Hydrogel samples were imaged using a FV1000 laser scanning confocal microscope (Olympus).

Measurement of stimuli-responsive intracellular Ca2+ flux

To evaluate the function of SGm within hydrogels, intracellular Ca2+ flux was measured in response to agonist stimulus as previous described36. To ensure fast diffusion of the ATP and CCh and immediate stimulation of SGm after addition, SGm were isolated from the hydrogel before calcium signaling experiments. Isolation also decreases hydrogel background during intracellular calcium flux imaging. Briefly, SGm were dissected from the hydrogel under microscopy at designated time points and incubated with 5 μM Fura-2 acetoxymethyl ester (AM) for 30 min at 37 °C after washing with PBS. Then 100 nM Carbachol or 100 μM ATP was added to stimulate the spheres for 180 s and the total duration time for Ca2+ measurement was 600 s. Intracellular Ca2+ flux was recorded using an inverted microscope (Nikon Diaphot 200) equipped with an imaging system (Till Photonics, Pleasanton, CA). The fluorescence ratio of 340 nm over 380 nm was calculated, and all data are presented as the change in fluorescent ratios.

Statistical analysis

All graphs are presented as mean ±standard deviation. At least three biological replicates were included in each group. Statistical significance between two groups was determined using Prism software (GraphPad) with p < 0.05 as the threshold for statistical significance unless otherwise indicated in legends. Statistics are analyzed using one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post-hoc test.

Results

Isolation of primary AIDUCs

Our previous work established that primary SGCs dissociated to either single or multiple cellular aggregates exhibit low viability when directly encapsulated within hydrogels22, 23. To counter the loss in viability, cells were previously cultured for 2 days under non-adherent conditions to form aggregates before hydrogel encapsulation. The viability of cells within the aggregates, which included both acinar and duct cells37, was significantly increased, suggesting that cell-cell interactions support survivability. Although the aggregates promoted viability, proliferation, and even exhibited evidence of cellular organization including apico-basolateral organization of acinar markers, there was a loss of acinar cell phenotype during aggregate formation with evidence for acinar transition to ductal phenotypes22, 30.

To maintain differentiated acini, a milder dissociation protocol was adapted to isolate AIDUCs35, 36, and the size distribution of the freshly isolated AIDUCs, analyzed using light microscopy, was 20–100 μm (Fig. S1). While comprised of both acinar and duct cells (Fig. S2A), most cells within AIDUCs are acinar cells, as indicated by the positive staining of acinar cell makers NKCC1 and AQP5 (Fig. S2A–C). Furthermore, cell-cell contacts were also investigated via immunostaining. The positive staining of ZO-1 and E-Cadherin indicated that cell-cell contacts were successfully maintained in AIDUCs (Fig. S2 B,C). Additionally, high cell viability (>95%) was achieved immediately following isolation (Fig. S3 A,B). After 2 days of culture under non-adherent conditions, unencapsulated AIDUC controls also formed aggregates (Fig. S3 C,D).

Formation of SGm within hydrogel microenvironments

AIDUCs were encapsulated in PEG hydrogels immediately after isolation and the viability of encapsulated AIDUCs was analyzed using LIVE/DEAD imaging at days 0, 4, 7, and 14 (Fig. 2A–D). In contrast to the low viability of cells encapsulated directly after isolation in our previous report23, high cell viability was observed over 14 days post-encapsulation. The same protocol was used to isolate human AIDUCs, which were subsequently encapsulated within PEG hydrogels. Our data show that encapsulated human AIDUCs maintain viability and self-assemble into SGm within the hydrogel (Fig. S4).

Fig. 2. Cell viability of hydrogel encapsulated AIDUCs.

LIVE/DEAD imaging of encapsulated AIDUCs at day 0 (A), day 4 (B), day 7 (C), day 14 (D) and blocked with ZO-1 (E) and E-Cadherin (F) antibody. Scale bars = 800 μm. (G) Quantification of sphere size at different time points after encapsulation. Viability of hydrogel encapsulated AIDUCs (H). ** p < 0.01, **** p < 0.0001 compared with day 0 determined using one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s correction for multiple comparisons test. N = 4.

To investigate the importance of cell-cell contacts on cell survivability, AIDUC interactions were blocked with antibodies against ZO-1 or E-Cadherin for 30 mins prior to encapsulation, resulting in few live cells at day 4 (Fig. 2E,F), indicating that preservation of cell-cell contacts directly contributes to cell survival after AIDUC encapsulation.

Over the 14-day culture period, there was a significant increase in SGm size. SGm expanded to ~100 ±19 μm by day 7 and continued to increase in size through day 14 to form structures of ~135 ±25 μm (Fig. 2G). Cell metabolic activity, a surrogate for proliferation, also increased 8-fold over 14 days, suggesting that proliferation may play a part in the observed increases in SGm size (Fig. 2H). We further stained for Ki67, which is a nuclear protein present at all stages of cell division (G1, S, G2, and mitosis) but not during the resting stage (G0)38. Abundant nuclear Ki67 was observed among peripheral cells of the SGm, again suggesting that cell proliferation within the SGm may play an important role in tissue development and organization during hydrogel culture (Fig. 3E).

Fig. 3. Cavity formation within AIDUCs involves apoptosis.

A representative phase (A) and fluorescent LIVE/DEAD (B) image of an acinar-like structure in hydrogel after culture for 14 days. Immunostaining of cell apoptosis marker, cleaved caspase 3, in SGm after 7 days (C) and 14 days (D) culture in hydrogels. (E) Proliferation of AIDUCs cultured in hydrogels assessed by Ki67 immunofluorescence staining. DAPI is used to stain nuclei.

To further investigate the underlying mechanism of increased tissue size, imaging was performed. Fluorescent and brightfield images of the SGm at day 14 are shown in Fig. 3A–B, some dead cells (red, Fig. 3B) were observed in the center of the structures.

Selective apoptosis at the center of a developing cell mass is essential to glandular organogensis39. To determine whether our SGm cultures developed in a similar fashion, cleaved caspase 3, an indicator of cell apoptosis, was stained. While the number of dead cells is relatively low in Fig. 3B, positive staining for cleaved-caspase-3, observed at the center of SGm at day 7 and 14, respectively (Fig. 3C, D), confirms the presence of apoptotic cells. Cells located in the interior of the aggregates do not have the same cell-cell contacts as the polarized epithelial surface cells, which may result in cell death. Previous studies by other groups have also observed dead cells and positive caspase-3 staining in the center of the acini-like structures when culturing salivary gland progenitor cells in various hydrogels20, 27, 40–43. Cavities with varying number and size were observed by day 14 (Fig. 3D, E), but they cannot be designated as lumens, as it is unclear how or when they are formed and whether they are polarized differently from the outer cell layer. We speculate that cells on the inside of the spheres may undergo apoptosis because they are excluded from cell-cell contacts found on the outside of the sphere.

SGm formed in hydrogels maintain expression of acinar cell markers

To further evaluate the effect of hydrogel encapsulation on acinar cell phenotypic maintenance, real time PCR was used to determine expression levels of acinar cell-specific markers. Significant decreases in Mist1, Nkcc1, Aqp5, and Ip3r3 expression were observed at day 14 when compared to freshly isolated AIDUCs (day 0) (Fig. 4A–D), consistent with our previous findings22, 30, 36. Specifically, expression was maintained at 1%, 4.7%, 0.22%, and 73%, respectively, compared with day 0 AIDUCs. Additionally, expression of duct and myoepithelial cell markers, cytokeratin 7 (K7) and cytokeratin 5 (K5), showed robust increases at day 14 of 5.9- and 9-fold higher versus day 0 levels (Fig. 4E, F). The myoepithelial marker, smooth muscle actin (Sma), exhibited only 13% expression at day 14 compared to day 0 level (Fig. 4G).

Fig. 4. Hydrogel encapsulated SGm express markers of all three major cell types in the salivary gland (acinar, duct and myoepithelial).

Quantitative PCR was used to measure gene expression of acinar cell markers Mist 1 (A), Nkcc1 (B), Aqp5 (C) and Ip3r3 (D), duct cell markers K7 (E) and K5 (F) and myoepithelial cell marker Sma (G) relative to the reporter gene Rps29 (ribosomal gene). Statistics are relative to Day 0, using one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post-hoc test. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 and **** p < 0.0001. N=4.

Hydrogel encapsulated SGm express salivary gland cell markers

The salivary gland is composed of acinar, duct, and myoepithelial cells. To characterize the morphology of SGm encapsulated in hydrogel, specific markers of these 3 cell types were examined using immunostaining. NKCC1 is a marker of acinar cells and localized at the basolateral membrane of acinar cells (Fig. 5A,B). NKCC1 remains basolaterally localized in the SGm encapsulated in hydrogels at day 14 (Fig. 5E,F). K7 and K5, which are duct and myoepithelial cell markers, were largely expressed at the periphery of the tissue mimetics (Fig. 5E,G), similar to the gland tissue (Fig. 5A,C). SMA is a myoepithelial cell marker, which showed staining that was peripherally localized in the aggregates (Fig. 5F). These data suggest that all three cell phenotypes responsible for gland function are present in SGm within hydrogels.

Fig. 5. Characterization of SGm with immunostaining at day 14.

Immunochemistry staining of protein expression in intact salivary gland tissue (A-D, I-L) and in SGm (E-H, M-P). Staining for acinar cell markers NKCC1 (A, B, E, F), AQP5 (D, H), IP3R3 (I, M), Duct cell markers K7 (A, E) and K5 (C, G), and myoepithelial cell marker αSMA (B, F), basement membrane proteins, Laminin (K,O) and Collagen IV (L, P), and tight junction protein ZO-1 (J, N). Scale bars = 40 μm.

AQP5, which is the primary water channel expressed on the apical membrane of acinar cells, plays an important role in secretion of fluid into the lumen of ducts by activation of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors. AQP5 staining is apically localized within SGm at day 14 (Fig. 5H). Inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate receptor 3 (IP3R3), a regulator of intracellular Ca2+ signaling, localizes at the apical membrane of acinar cells and staining of hydrogel-encapsulated SGm suggested similar spatial expression with luminal dominance (Fig. 5M).

Cell-cell junctions and apicobasal distribution of channel proteins are necessary to establish cell polarity and to maintain functional secretory cells44. To further assess epithelial polarization, the spatial distribution of tight junction proteins was examined through immunohistochemistry. Tight junctions (TJs) act as intermembrane barriers, preventing lateral movement of apically and basolaterally localized membrane proteins as well as the leakage of ions. ZO-1, a component of the TJ protein complex, is localized in the apical region of acinar and duct cells. ZO-1 staining suggested tight junction formation and apicobasolateral polarity especially within large, isolated cavities formed by day 14 in hydrogels (Fig. 5N). Basement membrane proteins laminin and collagen IV play important roles in promoting apicobasal polarity45 and are basolaterally localized in the gland (Fig. 5K,L) and in SGm at day 14 (Fig. 5O,P). Protein expression shown via immunostaining (Fig. 5 E–H, I and Fig. 6F, H) further supported the observed trends in gene expression (Fig. 4 and Fig. 6A, B).

Fig. 6. Hydrogel encapsulated SGm retain expression of secretory proteins.

Gene expression of the secretory proteins Amy1 (A), Pip (B), Muc5b (C) and Lyz2 (D) determined using qPCR. Immunohistochemical staining of Amylase (E,F) and PIP (G,H) in intact gland and SGm at day 14. Scale bars = 40 μm. All gene expression data is relative to day 0 with ribosomal gene Rps29. Statistics are relative to Day 0, using one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post-hoc test. *p < 0.05, and *** p < 0.001. N=4.

SGm encapsulated in hydrogels maintain secretory protein expression

To confirm the secretory function of the encapsulated SGm, the expression of secretory protein markers was analyzed. qPCR was used to detect prolactin-inducible protein (Pip), amylase (Amy1), mucin 5b (Muc5b), and lysozyme 2 (Lyz2). Relative to day 0 isolated AIDUCs, Amy1 expression was decreased to 5% at day 7 but rebounded to 15% by day 14 (Fig. 6A), and Pip expression was decreased to 0.002% at day 7 but increased to 0.2% by day 14 (Fig. 6B). Another secretory protein, Muc5b was decreased to 22% of day 0 controls at day 7 but expression increased to 35% by day 14 (Fig. 6C). Additionally, 24-fold up-regulation of Lyz2 expression was detected at day 14 compared to day 0 tissue (Fig. 6D), which may implicate a hypoxia-related stress response46.

Immunohistochemical staining was also used to characterize the expression of secretory proteins. Despite significantly reduced mRNA levels, protein expression of Amy1 (Fig. 6E,F) and PIP (Fig. 6G,H) was observed in intact gland and in day 14 SGm, confirming that secretory marker expression is well maintained in SGm.

Secretory function is maintained in SGm encapsulated in hydrogels

The muscarinic acetylcholine receptor 3 (M3r) is the major neurotransmitter receptor involved in salivary fluid secretion from acinar cells. Acinar cells also express several types of purinergic receptors, including P2Y2, a G protein-coupled protein receptor47. Activation of P2Y receptors leads to an increase in intracellular [Ca2+], which induces fluid secretion. The expression of these receptors in SGm was interrogated using qPCR. The expression of M3r decreased to 15% and 21% of primary AIDUCs at day 7 and day 14, respectively, which is consistent with acinar cell marker expression (Fig. 7A). Immunostaining was used to detect M3R expression in SGm (Fig. 7C). The expression of P2Y2 showed an increasing trend at both days 7 and 14, however, these increases are not significant due to data variability (Fig. 7B). TMEM16A plays a critical role in encoding the apical Ca2+-activated Cl− channel (CaCC) efflux pathway required for Ca2+-dependent fluid secretion48, 49. The robust expression of M3R and TMEM16A (Fig. 7D) indicate that the secretory function is successfully maintained in SGm.

Fig. 7. SGm in hydrogels are responsive to stimulation with muscarinic agonist carbachol (CCh) and purinergic agonist ATP.

Gene expression profiles of muscarinic receptor type 3 (M3r, A) and purinergic receptors (P2y2, B), in SGm at days 7 and 14. Immunostaining of M3r (C) and Tmem16A (D) at day 14 after encapsulation. Scale bar = 40 μm. Fluorescent calcium flux images of SGm before (E, I), and after (F, J) stimulation with 100 nM CCh and 100 μM ATP, and removal of stimuli (G, K). Quantitative analysis of Ca2+ signaling in SGm stimulated with CCh (H) and ATP (L). Dashed lines indicate that the stimuli were added at 60 s and removed at 240 s. All gene expression data is relative to day 0 with ribosomal gene Rps29. Statistics are relative to Day 0, using one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post-hoc test. **** p < 0.0001. N=4.

Calcium signaling plays a central role in saliva secretion and function. Functionality of the hydrogel-cultured SGm was assessed by analyzing intracellular calcium release after stimulation by muscarinic and purinergic agonists. Robust calcium response was observed after addition of the muscarinic agonist carbachol (CCh, Fig. 7E–H, Suppl. Video 1) and purinergic agonist ATP at 60s (Fig. 7I–L, Suppl. Video 2). CCh stimulates the M3 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor on acinar cells, leading to increased intracellular free calcium concentrations ([Ca2+]i) while ATP is an agonist of purinergic receptors on both acinar and duct cells. Calcium response gradually diminished after removal of CCh/ATP at 240s (Fig. 7G,K). Overall, robust agonist-stimulated calcium signaling suggested that hydrogel-cultured SGm maintained secretory functions.

Hydrogel encapsulated SGm exhibit acinar-to-ductal metaplasia

To lineage trace acinar cells, the tdTomato reporter was activated by inducing Mist1CreERT2;R26 tdTomato mice with tamoxifen 3 days prior to AIDUC isolation. Freshly isolated AIDUCs were encapsulated in hydrogels and cultured for 14 days in vitro before being fixed with 4% PFA for immunostaining. Both tdTomato+ acinar cells and non-labeled duct cells are present in freshly isolated AIDUCs (Fig. 8A), AQP5 is apically located on the tdTomato+ acinar cells and the majority of the cells are positive for NKCC1 (Fig. 8B,C). Quantification of the images showed that approximately 94% of acinar lineage cells co-expressed NKCC1.

Fig. 8. Salivary gland acinar cells exhibit plasticity after encapsulation in the hydrogels.

Immunostaining of freshly isolated AIDUCs from Mist1CreERT2/R26 tdTomato mouse with antibody to RFP (A), NKCC1 (B) and AQP5(C). EdU staining to evaluate the proliferation of SGm at day 14 (D). Arrowheads indicate cells from acinar lineage that are co-localized with EdU. Expression of NKCC1 and AQP5 is dysregulated in SGm encapsulated within hydrogels. Immunofluorescence staining of SGm with antibodies to AQP5 (E-H) and NKCC1 (I-L) shows co-localization with tdTomato-positive acinar cells at day 14. Arrowheads indicate cells from acinar lineage that are positive for NKCC1 (L), and AQP5 (H). Acinar lineage cells in encapsulated SGm activate expression of keratins. SGm in hydrogel at day 14 stained with antibodies to tdTomato (RFP) and K7 (M-P). SGm in hydrogel at day 14 stained with antibodies to tdTomato (RFP) and K14 (Q-T). Arrowheads indicate cells from acinar lineage that are co-localized with K7 (P), and K14 (T). Nuclei are stained with DAPI. Scale bar =20 μm.

Cell proliferation contributes to SGm size increase after encapsulation in the hydrogels, as indicated by positive Ki67 staining (Fig. 3E). However, it is still unclear which cells contribute to the proliferation. EdU staining was used to assess the cell proliferation within hydrogel encapsulated SGm (Fig. 8D). While imaging suggested acinar cells (red) persist in culture for up to 14 days and both acinar (arrowhead) and non-acinar cells are proliferating, most of the proliferation occurred in non-acinar cells (Fig. 8D).

To further investigate the fate of acinar cells following hydrogel encapsulation for 14 days, co-expression of tdTomato with AQP5 (Fig. 8E–H) and NKCC1 (Fig. 8I–L) was analyzed using immunofluorescence staining. Approximately 25% acinar lineage cells co-expressed AQP5 (Fig. 8H, arrowheads) while ~67% co-localized with NKCC1+ cells (Fig. 8L, arrowheads).

Co-expression of tdTomato with duct cell markers K7 and K14 was also assessed. Immunostaining showed ~67% acinar lineage cells co-localized with K7+ cells (Fig. 8M–P, arrowheads). For K14+ cells, ~38% acinar lineage cells co-expressed K14 (Fig. 8Q–T, arrowheads). These results indicated that hydrogel encapsulated AIDUCs underwent some acinar-to-ductal metaplasia over time based on the expression of duct cell-specific markers by cells of the acinar cell-lineage.

Discussion

Maintenance or development of functional salivary gland units for transplantation within a biocompatible hydrogel matrix that enables integration into damaged glands is a key step toward creation of a functional tissue-engineered salivary gland. In this study, functional salivary gland tissues were developed ex vivo by entrapping primary AIDUCs within engineered extracellular matrices, instead of pre-formed aggregates or singular SGCs used in our previous studies22, 23, 30. Our data show that AIDUCs encapsulated within MMP-degradable PEG hydrogels form acinar-like units with phenotypic and functional characteristics consistent with the native salivary gland. Hydrogel-encapsulated AIDUCs showed long-term cell viability, maintained expression of acinar-related genes and proteins, and exhibited polarized localization of basement and secretory membrane proteins, as well as cellular organization. Remarkably, hydrogel-cultured SGm also retained the ability to respond to Ca2+ agonists.

Cell-cell interactions were found to be particularly critical for survival and function of encapsulated AIDUCs. When cell-cell contacts in freshly isolated AIDUCs were blocked with antibodies against ZO-1 or E-Cadherin, survivability was significantly reduced. Cell-cell interactions occur via specialized adhesion junctions and regulate a variety of functions in multicellular organisms, including survival, differentiation, barrier formation, tissue function and signal transduction50–52. The absence of cell-cell contacts in dispersed primary SGCs renders them unable to survive, proliferate, self-assemble, and re-aggregate to form functional acinar units23. By utilizing a milder cell isolation procedure, cell-cell contacts and apicobasolateral organization was well preserved in AIDUCs, contributing to cell viability and proliferation and function23, 52, 53.

Long-term maintenance of the acinar cell phenotype in vitro is a challenge in salivary gland tissue engineering approaches. Previous studies have shown that 3D culture of SGCs in various hydrogels improved maintenance of acinar cell marker expression, including α-amylase, Aqp5, Mist1, and Nkcc1 compared with traditional 2D culture22, 24, 54–59. Nevertheless, significant reductions in acinar marker expression of Mist1, amylase, and Aqp5 are still observed. By encapsulating AIDUCs in our hydrogel system, a 1.1-fold and 2.1-fold increase of Mist1 and Nkcc1 expression level is observed at day 14 compared to our previous studies22, 30. Despite this advantage, the overall acinar gene expression level is still lower than native tissue. However, IHC staining of acinar cell phenotypic and functional protein markers, including NKCC1, AQP5, PIP and Amylase, showed consistent expression with intact glands, which is similar to previous studies using other hydrogel chemistries19–22, 27, 30, 54–57 and indicates the importance of the 3D environment of ECM on acinar cell phenotypic maintenance. Calcium signaling plays a central role in saliva secretion and function. SGm removed from hydrogels were tested for CCh and ATP responsiveness using calcium flux analysis. Robust calcium flux was observed upon stimulation with both agonists, indicating successful maintenance of secretory function, similar to previous findings24, 59–61. These data indicate the advantage of well-maintained cell-cell contacts in AIDUCs, as well as the engineered ECM, in maintaining acinar cell phenotype and secretory function.

Acinar-to-ductal metaplasia has been described for both primary cultured pancreatic and salivary gland acinar cells30, 31, and is accompanied with loss of Mist1 expression and increased expression of duct-specific genes31, 62, 63, resulting in cellular disorganization, changes in polarity and loss of secretory function63, 64. Freshly isolated AIDUCs are comprised of both acinar and duct cells, with most cells of acinar origin (>90%, Fig. S2). However, after encapsulation in hydrogels for 14 days, both gene expression data and lineage tracing of Mist1 in encapsulated SGm showed decreased expression levels, and increased expression of duct cell markers K5 (~9 fold) and K7 (~5.9 fold), which is consistent with the phenomenon of acinar-to-ductal metaplasia induced by acute injury or stress30, 31, 65. However, this study reports reduced metaplasia compared to our previous study30, which might be due to the preservation of cell-cell contacts in AIDUCs that relieved stress associated with cell isolation and promoted self-aggregation and tissue function of SGm.

Reduction or inhibition of acinar-to-ductal metaplasia would benefit the long-term in vitro culture of SGCs, maintenance of acinar cell phenotype, and development of cell-transplantation therapies for salivary gland regeneration. Inhibition of Mist1 transcriptional activity in pancreatic acinar cells leads to activation of duct-specific genes, such as K7, K19, and K2063. However, the incidence of acinar-to-ductal metaplasia was significantly attenuated by forced expression of Mist166. Small molecules such as Baicalein and GRP78 have been shown to inhibit the acinar-to-ductal metaplasia process by modulating the inflammatory microenvironment or reducing EGFR expression and blocking downstream RAS and AKT signaling pathways67, 68. Numb, κB-Ras, and Ral GTPases were also reported to regulate acinar-to-ductal metaplasia by inhibiting Notch and EGFR/KRas signaling69, 70. Suppression of acinar-to-ductal metaplasia using functional molecules to block specific signaling pathways, such as EGFR, TGF-β1 receptor, and ROCK may also prove useful to maintain salivary gland acinar cell phenotype and function in vitro68, 71–73.

Further studies can be undertaken to further engineer the hydrogel matrix to enhance maintenance of the acinar cell phenotype and to suppress acinar-to-ductal metaplasia. For example, the mode of hydrogel degradation has a significant impact on the organization and phenotype maintenance of SGm22, 23, MMP-degradable hydrogels enhanced tissue polarization and acinar cell marker expression through cellular remodeling based on controls of hydrolytically-degradable or non-degradable hydrogels22. Using these hydrogels, we have recently developed an engineered salivary gland tissue chip, which can be used for high-throughput and high-content screening of potential matrix cues and soluble cues that may further promote salivary gland acinar cell phenotype maintenance36. The rational design of hydrogel ECM degradable properties is likely to benefit functional outcomes of in vitro cultured SGCs. Numerous ECM proteins, especially basement membrane proteins, including laminin, collagen IV, and perlecan/HSPG2, are implicated in salivary gland development40, 45, 74, 75. SGCs cultured on fibrin hydrogel surfaces in the presence of laminin-111 protein and peptide derivatives, such as YIGSR, A99, RGD, and KP24, promoted salivary gland growth, lumen formation, and expression of secretory proteins24, 76–79. Soluble factors, including neurotrophic factors (neurturin and glial derived growth factor)80–84 and FGFs (FGF2, FGF7 and FGF10)11, 73, 85–87, have been reported to prevent stress responses and promote salivary gland development and acinar cell phenotype maintenance. Additionally, the study of matrix cues to maintain salivary gland function will be another topic of future investigations.

The in vivo environment is very complex compared to in vitro. Various soluble factors, including growth factors, small molecules, and cytokines, affect fate of the encapsulated cells and degradation of the implanted hydrogel. In our previous research, various hydrogels have been successfully used to transplant cells in vivo for tissue regeneration88–94, including MMP-degradable and hydrolytically degradable hydrogels, and contributions to tissue regeneration were promising. MMP-degradable PEG hydrogel-based tissue engineered periosteum (TEP) improved bone allograft healing by promoting rapid neurovascularization and hard bone callus formation versus hydrolytically degradable TEP modified allografts89. MMP-degradable hydrogels have also been used by others for tissue regeneration and promoted tissue integration after implantation95–98. Together, these data demonstrate that hydrogels are a promising platform for regeneration of functional salivary gland tissue in vivo. Allograft or xenograft transplantation is currently feasible using our approach. Unfortunately autografts are infeasible, as our current hydrogels do not sustain tissue function commensurate with the time frame over which fractionated irradiation treatments for head and neck cancers occur, as would be required based on tissue isolation prior to treatment/damage. Nevertheless, with continued development it may be possible to support longer term function, enabling an autograft approach

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that cell-cell interactions together with encapsulation within MMP-degradable PEG hydrogels can be used to maintain salivary gland tissue phenotype and function in vitro. We show that encapsulated AIDUCs exhibited long-term cell survivability and reorganized into acinar-like units composed of well-differentiated functional acinar, ductal, and myoepithelial structures. 3D-assembled SGm expressed salivary phenotypic markers and TJ proteins. They also exhibited secretory function as indicated by amylase and Pip staining and intracellular calcium flux, as well as reduced acinar-to-ductal metaplasia compared to our previous studies. These results highlight the utility of the MMP-degradable hydrogel platform, as well as the importance of maintaining cell-cell contacts in AIDUCs for the acinar cell phenotype and functional maintenance. In sum, PEG hydrogels are a promising platform for further investigation into the interactions required for regeneration of functional salivary gland tissue.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR), and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) of the National Institutes of Health, under award numbers UG3DE027695 and UH3DE027695, T32 ES007026, F31 DE029658 and the Training Program in Oral Sciences T90DE021985/R90DE022529. The authors would like to thank Dr. David Yule for training and access to calcium imaging equipment.

References

- 1.Bray F et al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians 68, 394–424 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seiwert TY, Salama JK & Vokes EE The chemoradiation paradigm in head and neck cancer. Nat Clin Pract Oncol 4, 156–171 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seiwert TY & Cohen EEW State-of-the-art management of locally advanced head and neck cancer. Brit J Cancer 92, 1341–1348 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wijers OB et al. Patients with head and neck cancer cured by radiation therapy: A survey of the dry mouth syndrome in long-term survivors. Head Neck-J Sci Spec 24, 737–747 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cassolato SF & Turnbull RS Xerostomia: clinical aspects and treatment. Gerodontology 20, 64–77 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haddad P & Karimi M A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of concomitant pilocarpine with head and neck irradiation for prevention of radiation-induced xerostomia. Radiother Oncol 64, 29–32 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sugito T, Kagami H, Hata K, Nishiguchi H & Ueda M Transplantation of cultured salivary gland cells into an atrophic salivary gland. Cell Transplant 13, 691–699 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dos Santos HT et al. Cell Sheets Restore Secretory Function in Wounded Mouse Submandibular Glands. Cells 9, 2645 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lombaert IMA et al. Rescue of Salivary Gland Function after Stem Cell Transplantation in Irradiated Glands. Plos One 3 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nanduri LSY et al. Salisphere derived c-Kit(+) cell transplantation restores tissue homeostasis in irradiated salivary gland. Radiother Oncol 108, 458–463 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sui Y et al. Generation of functional salivary gland tissue from human submandibular gland stem/progenitor cells. Stem Cell Res Ther 11, 127 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lim JY et al. Intraglandular transplantation of bone marrow-derived clonal mesenchymal stem cells for amelioration of post-irradiation salivary gland damage. Oral Oncol 49, 136–143 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.An HY et al. Adipose Mesenchymal Stem Cell Secretome Modulated in Hypoxia for Remodeling of Radiation-Induced Salivary Gland Damage. Plos One 10 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim JW et al. Adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells regenerate radioiodine-induced salivary gland damage in a murine model. Scientific reports 9, 15752 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Almansoori AA, Khentii N, Kim B, Kim SM & Lee JH Mesenchymal Stem Cell Therapy in Submandibular Salivary Gland Allotransplantation: Experimental Study. Transplantation 103, 1111–1120 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cantara SI et al. Selective functionalization of nanofiber scaffolds to regulate salivary gland epithelial cell proliferation and polarity. Biomaterials 33, 8372–8382 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jean-Gilles R et al. Novel Modeling Approach to Generate a Polymeric Nanofiber Scaffold for Salivary Gland Cells. Journal of nanotechnology in engineering and medicine 1, 31008 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Soscia DA et al. Salivary gland cell differentiation and organization on micropatterned PLGA nanofiber craters. Biomaterials 34, 6773–6784 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burghartz M et al. Development of Human Salivary Gland-Like Tissue In Vitro. Tissue Eng Pt A 24, 301–309 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ozdemir T et al. Tuning Hydrogel Properties to Promote the Assembly of Salivary Gland Spheroids in 3D. Acs Biomater Sci Eng 2, 2217–2230 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shin K et al. Three-Dimensional Culture of Salivary Gland Stem Cell in Orthotropic Decellularized Extracellular Matrix Hydrogels. Tissue Eng Pt A (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shubin AD et al. Encapsulation of primary salivary gland cells in enzymatically degradable poly(ethylene glycol) hydrogels promotes acinar cell characteristics. Acta Biomater 50, 437–449 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shubin AD, Felong TJ, Graunke D, Ovitt CE & Benoit DSW Development of Poly(Ethylene Glycol) Hydrogels for Salivary Gland Tissue Engineering Applications. Tissue Eng Pt A 21, 1733–1751 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nam K, Jones JP, Lei P, Andreadis ST & Baker OJ Laminin-111 Peptides Conjugated to Fibrin Hydrogels Promote Formation of Lumen Containing Parotid Gland Cell Clusters. Biomacromolecules 17, 2293–2301 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aframian DJ et al. Tissue compatibility of two biodegradable tubular scaffolds implanted adjacent to skin or buccal mucosa in mice. Tissue Eng 8, 649–659 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Joraku A, Sullivan CA, Yoo JJ & Atala A Tissue engineering of functional salivary gland tissue. Laryngoscope 115, 244–248 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pradhan-Bhatt S et al. Implantable Three-Dimensional Salivary Spheroid Assemblies Demonstrate Fluid and Protein Secretory Responses to Neurotransmitters. Tissue Eng Pt A 19, 1610–1620 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yamachika S et al. Excessive synthesis of matrix metalloproteinases in exocrine tissues of NOD mouse models for Sjogren’s syndrome. The Journal of rheumatology 25, 2371–2380 (1998). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Muramatsu T, Ohta K, Asaka M, Kizaki H & Shimono M Expression and distribution of osteopontin and matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-3 and −7 in mouse salivary glands. European journal of morphology 40, 209–212 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shubin AD et al. Stress or injury induces cellular plasticity in salivary gland acinar cells. Cell and tissue research 380, 487–497 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Means AL et al. Pancreatic epithelial plasticity mediated by acinar cell transdifferentiation and generation of nestin-positive intermediates. Development 132, 3767–3776 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aure MH, Konieczny SF & Ovitt CE Salivary gland homeostasis is maintained through acinar cell self-duplication. Developmental cell 33, 231–237 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fairbanks BD et al. A Versatile Synthetic Extracellular Matrix Mimic via Thiol-Norbornene Photopolymerization. Adv Mater 21, 5005–5010 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Van Hove AH, Beltejar MJ & Benoit DS Development and in vitro assessment of enzymatically-responsive poly(ethylene glycol) hydrogels for the delivery of therapeutic peptides. Biomaterials 35, 9719–9730 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Seo YJ et al. Cell culture of differentiated human salivary epithelial cells in a serum-free and scalable suspension system: The salivary functional units model. Journal of tissue engineering and regenerative medicine 13, 1559–1570 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Song Y et al. Development of a functional salivary gland tissue chip with potential for high-content drug screening. Communications biology 4, 361 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Varghese JJ et al. Salivary gland cell aggregates are derived from self-organization of acinar lineage cells. Archives of oral biology 97, 122–130 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Urruticoechea A, Smith IE & Dowsett M Proliferation marker Ki-67 in early breast cancer. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 23, 7212–7220 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mailleux AA, Overholtzer M & Brugge JS Lumen formation during mammary epithelial morphogenesis: insights from in vitro and in vivo models. Cell cycle 7, 57–62 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pradhan S et al. Lumen formation in three-dimensional cultures of salivary acinar cells. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery 142, 191–195 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim D, Yoon YJ, Choi D, Kim J & Lim JY 3D Organoid Culture From Adult Salivary Gland Tissues as an ex vivo Modeling of Salivary Gland Morphogenesis. Frontiers in cell and developmental biology 9, 698292 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Barrows CML, Wu D, Farach-Carson MC & Young S Building a Functional Salivary Gland for Cell-Based Therapy: More than Secretory Epithelial Acini. Tissue engineering. Part A 26, 1332–1348 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Szlavik V et al. Matrigel-induced acinar differentiation is followed by apoptosis in HSG cells. Journal of cellular biochemistry 103, 284–295 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Baker OJ Tight junctions in salivary epithelium. Journal of biomedicine & biotechnology 2010, 278948 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sequeira SJ, Larsen M & DeVine T Extracellular matrix and growth factors in salivary gland development. Frontiers of oral biology 14, 48–77 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hedtjarn M, Mallard C, Eklind S, Gustafson-Brywe K & Hagberg H Global gene expression in the immature brain after hypoxia-ischemia. Journal of cerebral blood flow and metabolism : official journal of the International Society of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism 24, 1317–1332 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang Z et al. The purinergic receptor P2Y, G-protein coupled, 2 (P2RY2) gene associated with essential hypertension in Japanese men. Journal of human hypertension 24, 327–335 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yang YD et al. TMEM16A confers receptor-activated calcium-dependent chloride conductance. Nature 455, 1210–1215 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Romanenko VG et al. Tmem16A encodes the Ca2+-activated Cl- channel in mouse submandibular salivary gland acinar cells. The Journal of biological chemistry 285, 12990–13001 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Baptista CA, Hatten ME, Blazeski R & Mason CA Cell-cell interactions influence survival and differentiation of purified Purkinje cells in vitro. Neuron 12, 243–260 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Green KJ, Getsios S, Troyanovsky S & Godsel LM Intercellular junction assembly, dynamics, and homeostasis. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology 2, a000125 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wei Q, Hariharan V & Huang H Cell-cell contact preserves cell viability via plakoglobin. Plos One 6, e27064 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jiao Q et al. Cell-Cell Connection Enhances Proliferation and Neuronal Differentiation of Rat Embryonic Neural Stem/Progenitor Cells. Frontiers in cellular neuroscience 11, 200 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Maria OM, Zeitouni A, Gologan O & Tran SD Matrigel improves functional properties of primary human salivary gland cells. Tissue engineering. Part A 17, 1229–1238 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Srinivasan PP et al. Primary Salivary Human Stem/Progenitor Cells Undergo Microenvironment-Driven Acinar-Like Differentiation in Hyaluronate Hydrogel Culture. Stem cells translational medicine 6, 110–120 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Joraku A, Sullivan CA, Yoo J & Atala A In-vitro reconstitution of three-dimensional human salivary gland tissue structures. Differentiation; research in biological diversity 75, 318–324 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shin HS et al. Functional spheroid organization of human salivary gland cells cultured on hydrogel-micropatterned nanofibrous microwells. Acta Biomater 45, 121–132 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shin HS, Hong HJ, Koh WG & Lim JY Organotypic 3D Culture in Nanoscaffold Microwells Supports Salivary Gland Stem-Cell-Based Organization. Acs Biomater Sci Eng 4, 4311–4320 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dos Santos HT et al. Trimers Conjugated to Fibrin Hydrogels Promote Salivary Gland Function. Journal of dental research, 22034520964784 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ozdemir T et al. Bottom-up assembly of salivary gland microtissues for assessing myoepithelial cell function. Biomaterials 142, 124–135 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yoshimoto S et al. Inhibition of Alk signaling promotes the induction of human salivary-gland-derived organoids. Disease models & mechanisms 13 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Karki A et al. Silencing Mist1 Gene Expression Is Essential for Recovery from Acute Pancreatitis. Plos One 10, e0145724 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhu L et al. Inhibition of Mist1 homodimer formation induces pancreatic acinar-to-ductal metaplasia. Molecular and cellular biology 24, 2673–2681 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Johnson CL, Kowalik AS, Rajakumar N & Pin CL Mist1 is necessary for the establishment of granule organization in serous exocrine cells of the gastrointestinal tract. Mechanisms of Development 121, 261–272 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Weng PL, Aure MH, Maruyama T & Ovitt CE Limited Regeneration of Adult Salivary Glands after Severe Injury Involves Cellular Plasticity. Cell reports 24, 1464–1470 e1463 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Shi G et al. Maintenance of acinar cell organization is critical to preventing Kras-induced acinar-ductal metaplasia. Oncogene 32, 1950–1958 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pu WL et al. Baicalein inhibits acinar-to-ductal metaplasia of pancreatic acinal cell AR42J via improving the inflammatory microenvironment. Journal of cellular physiology 233, 5747–5755 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shen J et al. GRP78 haploinsufficiency suppresses acinar-to-ductal metaplasia, signaling, and mutant Kras-driven pancreatic tumorigenesis in mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 114, E4020–E4029 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Beel S et al. kappaB-Ras and Ral GTPases regulate acinar to ductal metaplasia during pancreatic adenocarcinoma development and pancreatitis. Nature communications 11, 3409 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Greer RL, Staley BK, Liou A & Hebrok M Numb regulates acinar cell dedifferentiation and survival during pancreatic damage and acinar-to-ductal metaplasia. Gastroenterology 145, 1088–1097 e1088 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Koslow M, O’Keefe KJ, Hosseini ZF, Nelson DA & Larsen M ROCK inhibitor increases proacinar cells in adult salivary gland organoids. Stem Cell Res 41, 101608 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Liu J et al. TGF-beta1 promotes acinar to ductal metaplasia of human pancreatic acinar cells. Scientific reports 6, 30904 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Piraino LR, Benoit DSW & DeLouise LA Salivary Gland Tissue Engineering Approaches: State of the Art and Future Directions. Cells 10 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Virtanen I et al. Laminin alpha1-chain shows a restricted distribution in epithelial basement membranes of fetal and adult human tissues. Experimental cell research 257, 298–309 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Caselitz J, Schmitt P, Seifert G, Wustrow J & Schuppan D Basal membrane associated substances in human salivary glands and salivary gland tumours. Pathology, research and practice 183, 386–394 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Maruyama CL et al. Stem Cell-Soluble Signals Enhance Multilumen Formation in SMG Cell Clusters. Journal of dental research 94, 1610–1617 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Nam K et al. L1 Peptide-Conjugated Fibrin Hydrogels Promote Salivary Gland Regeneration. Journal of dental research 96, 798–806 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Taketa H et al. Peptide-modified Substrate for Modulating Gland Tissue Growth and Morphology In Vitro. Scientific reports 5, 11468 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ikeda A et al. Functional peptide KP24 enhances submandibular gland tissue growth in vitro. Regenerative therapy 3, 108–113 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ferreira JN & Hoffman MP Interactions between developing nerves and salivary glands. Organogenesis 9, 199–205 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ferreira JNA et al. Neurturin Gene Therapy Protects Parasympathetic Function to Prevent Irradiation-Induced Murine Salivary Gland Hypofunction. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev 9, 172–180 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Knox SM et al. Parasympathetic innervation maintains epithelial progenitor cells during salivary organogenesis. Science 329, 1645–1647 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Peng X, Varendi K, Maimets M, Andressoo JO & Coppes RP Role of glial-cell-derived neurotrophic factor in salivary gland stem cell response to irradiation. Radiother Oncol 124, 448–454 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Xiao N et al. Neurotrophic factor GDNF promotes survival of salivary stem cells. J Clin Invest 124, 3364–3377 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hosseini ZF et al. FGF2-dependent mesenchyme and laminin-111 are niche factors in salivary gland organoids. J Cell Sci 131 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Adine C, Ng KK, Rungarunlert S, Souza GR & Ferreira JN Engineering innervated secretory epithelial organoids by magnetic three-dimensional bioprinting for stimulating epithelial growth in salivary glands. Biomaterials 180, 52–66 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Miyajima H et al. Hydrogel-based biomimetic environment for in vitro modulation of branching morphogenesis. Biomaterials 32, 6754–6763 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Van Hove AH, Burke K, Antonienko E, Brown E 3rd & Benoit DS Enzymatically-responsive pro-angiogenic peptide-releasing poly(ethylene glycol) hydrogels promote vascularization in vivo. Journal of controlled release : official journal of the Controlled Release Society 217, 191–201 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Li Y, Hoffman MD & Benoit DSW Matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-degradable tissue engineered periosteum coordinates allograft healing via early stage recruitment and support of host neurovasculature. Biomaterials 268, 120535 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wang Y, Zhang S & Benoit DSW Degradable poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG)-based hydrogels for spatiotemporal control of siRNA/nanoparticle delivery. Journal of controlled release : official journal of the Controlled Release Society 287, 58–66 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wang Y, Malcolm DW & Benoit DSW Controlled and sustained delivery of siRNA/NPs from hydrogels expedites bone fracture healing. Biomaterials 139, 127–138 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hoffman MD & Benoit DS Emulating native periosteum cell population and subsequent paracrine factor production to promote tissue engineered periosteum-mediated allograft healing. Biomaterials 52, 426–440 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hoffman MD, Van Hove AH & Benoit DS Degradable hydrogels for spatiotemporal control of mesenchymal stem cells localized at decellularized bone allografts. Acta Biomater 10, 3431–3441 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hoffman MD, Xie C, Zhang X & Benoit DS The effect of mesenchymal stem cells delivered via hydrogel-based tissue engineered periosteum on bone allograft healing. Biomaterials 34, 8887–8898 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Cai Z et al. Capturing dynamic biological signals via bio-mimicking hydrogel for precise remodeling of soft tissue. Bioactive materials 6, 4506–4516 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lueckgen A et al. Enzymatically-degradable alginate hydrogels promote cell spreading and in vivo tissue infiltration. Biomaterials 217, 119294 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Lutolf MP et al. Synthetic matrix metalloproteinase-sensitive hydrogels for the conduction of tissue regeneration: engineering cell-invasion characteristics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 100, 5413–5418 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Contessotto P et al. Elastin-like recombinamers-based hydrogel modulates post-ischemic remodeling in a non-transmural myocardial infarction in sheep. Science translational medicine 13 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.