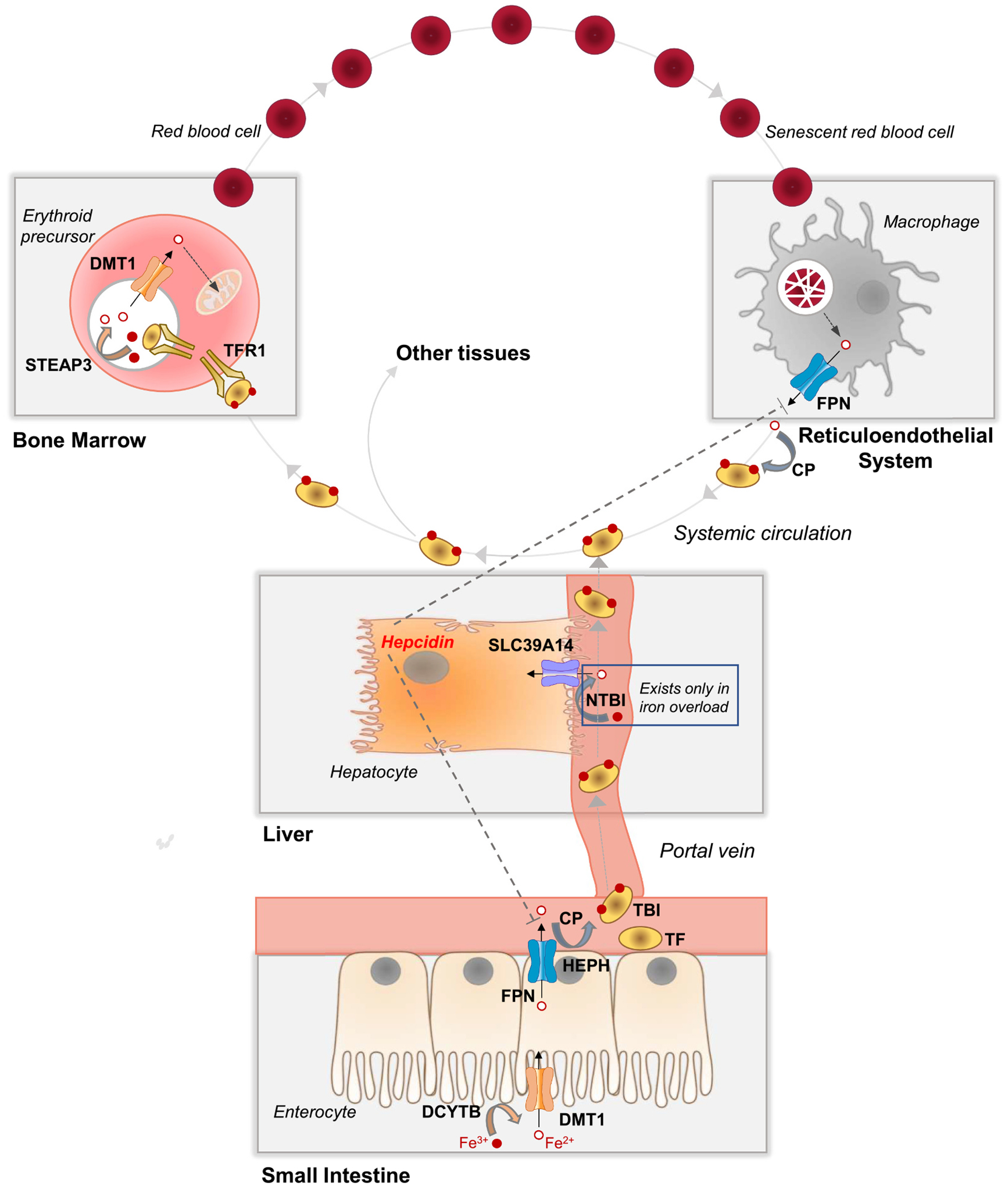

Fig. 1.

Whole-body iron transport, metabolism, and distribution. In the small intestine, dietary non-heme iron, which exists mainly as Fe3+, is converted to Fe2+ by a reductase (e.g., DCYTB, cytochrome B reductase 1) prior to transport into the enterocyte via DMT1 (divalent metal-ion transporter-1) at the apical membrane. FPN (ferroportin) at the enterocyte basolateral membrane transports Fe2+ into capillary blood, where it is oxidized by a ferroxidase (e.g., HEPH, hephaestin, or CP, ceruloplasmin) to Fe3+, which binds to plasma TF (transferrin) to become TBI (transferrin-bound iron). TBI travels via the portal vein through the liver and into systemic circulation, where it delivers iron to the bone marrow and other tissues. Bone marrow erythroid precursor cells take up TBI via TFR1 (transferrin receptor 1)-mediated endocytosis. Endosomal acidification and reduction by STEAP3 (six-transmembrane epithelial antigen of the prostate 3) releases Fe2+, which is transported out of the endosome via DMT1. Fe2+ is taken up via mitoferrin 1 into the mitochondria, where it is incorporated into protoporphyrin IX to become heme, which is used mainly for hemoglobin synthesis in immature red blood cells. Red blood cells circulate for ~120 days and are then cleared from the circulation via macrophages of the reticuloendothelial system (i.e., macrophages of the liver, spleen, and bone marrow). Senescent red blood cells are taken up by macrophages via phagocytosis. Internalized red blood cells are degraded in the lysosome and heme is degraded to release Fe2+, which is transported via FPN into the plasma, where it binds to TF, thereby recycling red blood cell iron. In iron overload, the iron-carrying capacity of TF become exceeded giving rise to NTBI (non-transferrin-bound iron), a pathological form of iron that is a major contributor to tissue iron loading. Additional details are described in Section 2.1.