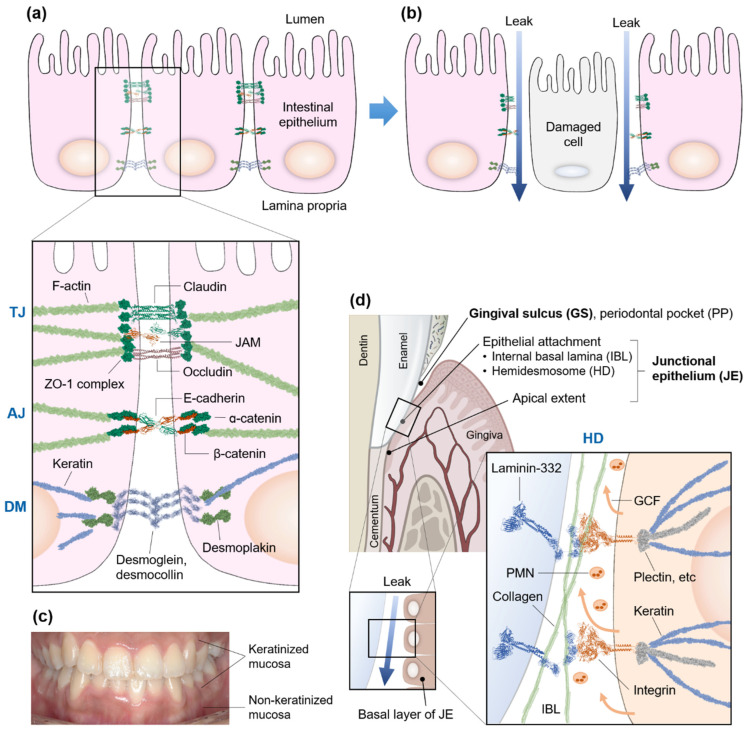

Figure 1.

Schematics of differences in the cellular junctions between the intestinal and oral epithelia. (a) The intestinal epithelia are interconnected and communicate with each other through junctions, such as tight junction (TJ), adherence junction (AJ), desmosome (DM), and gap junction (GJ, not shown). (b) When these barriers are disrupted because of epithelial damages, pathogens, and chemicals in the luminal side can leak through the damaged cellular gaps into the lamina propria (blue arrows) whereby the MALT implements immune responses, resulting in a leaky gut syndrome. (c) Keratinized and non-keratinized oral mucosa. (d) Unlike the intestinal leakage through the cell-to-cell junctions, the leakage in the oral mucosa occurs through the hemidesmosome (HD) between the basal layer of the junctional epithelium (JE) and the hard surface layer of a tooth, which is inevitably and more frequently exposed to the physical and biological challenges. The internal basal lamina (IBL), an HD interface, is inhabited with collagens and binding proteins, such as laminin-332 and integrin. The periodontal pocket (PP), a pathologically deepened gingival sulcus (GS), occurs with the detachment of the connective tissues of the gingiva from the tooth surface. The JE below the GS is ~0.15 mm wide and 1–2 mm high, remains non-keratinized and undifferentiated, and has the highest turnover rate (4–6 days) of all oral epithelia. The polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs) are also secreted with gingival crevicular fluid (GCF) from the basal layer to keep a lookout for any hostile intruders. ZO-1: zonula occludens-1, JAM: junctional adhesion molecule.