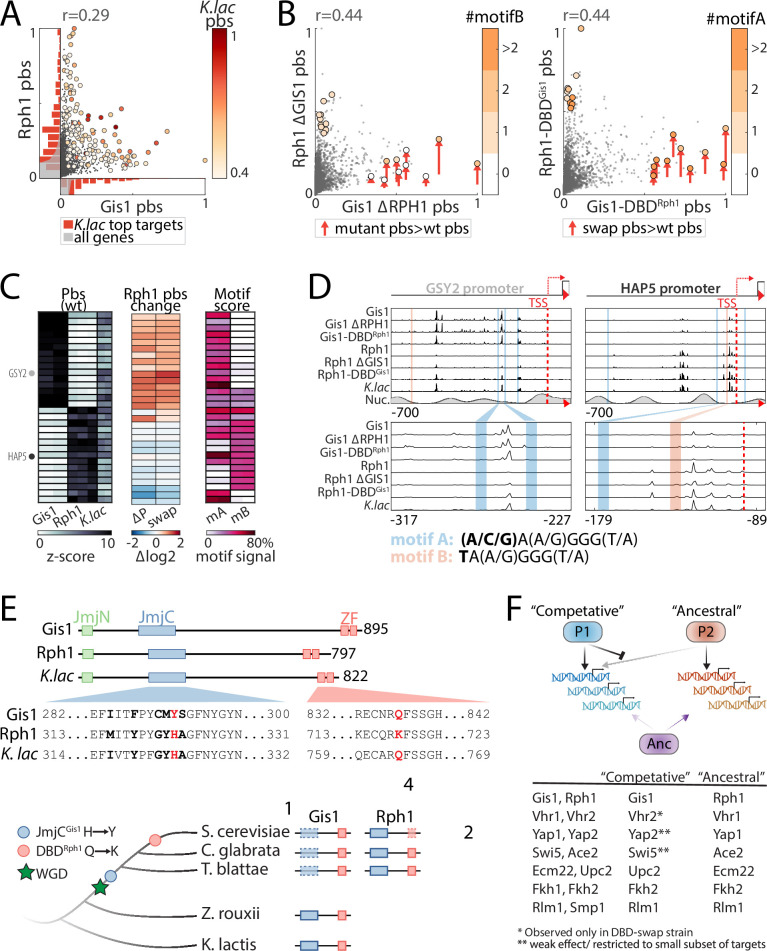

Figure 9. Resolution of paralog interference through competitive binding.

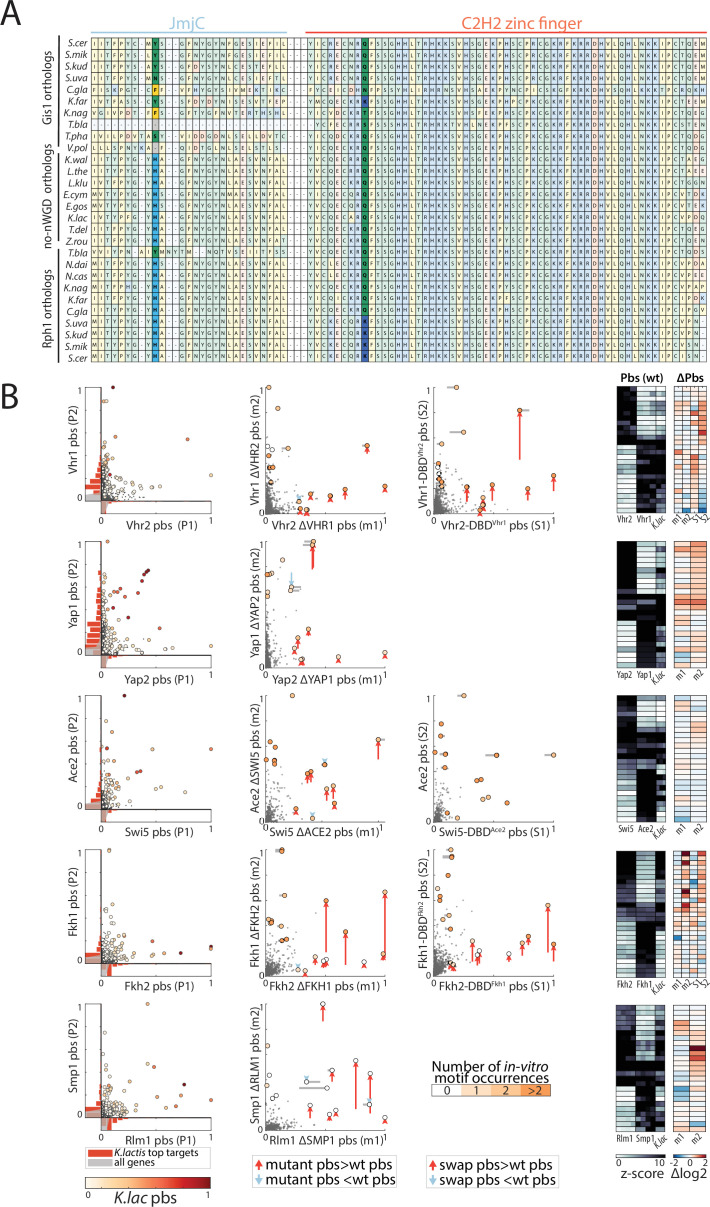

(A–D) Gis1 limits Rph1 binding through DNA-binding domain (DBD)-dependent competition: shown are promoter-binding preferences of Gis1 and Rph1 in wild-type backgrounds (A, as in Figure 8C) and following mutual paralog deletion and DBD-swapping (B, colored by the number of occurrences of the two known motif variants specified in D). The analysis of all top-bound promoters is summarized in (C) (columns correspond to individual repeats) and binding signals on exemplary promoters are shown in (D) (as described in Figure 8A). Note the increased binding of Rph1 to Gis1 target promoters (e.g. GSY2) upon GIS1 deletion or DBD-swapping (in wild-type background), and reduced Gis1 binding to its target promoter after DBD-swapping (e.g. HAP5). (E) Gis1’s loss of demethylase activity preceded variation in Rph1’s DBD: The conserved JmjC domain providing Rph1 a histone demethylase activity is mutated in Gis1 orthologs of all post-WGD species. The respective DBDs differ in only four positions, at one of which a conserved glutamine is replaced by lysine specifically in Rph1 and its closest orthologs (Figure 9—figure supplement 1). This suggests that the divergence was triggered by the loss of demethylase function and DBD-independent acquisition of new targets by Gis1, and a final mutation in Rph1-DBD to reduce residual Rph1-binding interference at the newly acquired Gis1 sites (blue box: JmjC domain, red box: DBD, dashed box: mutated domain). (F) Resolution of paralog interference among diverging transcription factor (TF) paralogs: A model for the resolution of paralog interference through competitive binding. The TF inhibiting its paralog’s binding is denoted as ‘competitive’, while the TF whose binding preferences better resemble those of the Kluyveromyces lactis ortholog is denoted as ‘ancestral’. In addition to Gis1/Rph1, other diverging paralogs whose K. lactis orthologs were profiled appear to conform to this general model (Figure 9—figure supplement 1). Note that in most cases (indicated), divergence in promoter binding is driven by variations outside the DBD, with competition only refining, but not driving this divergence of target preferences.