Figure 5.

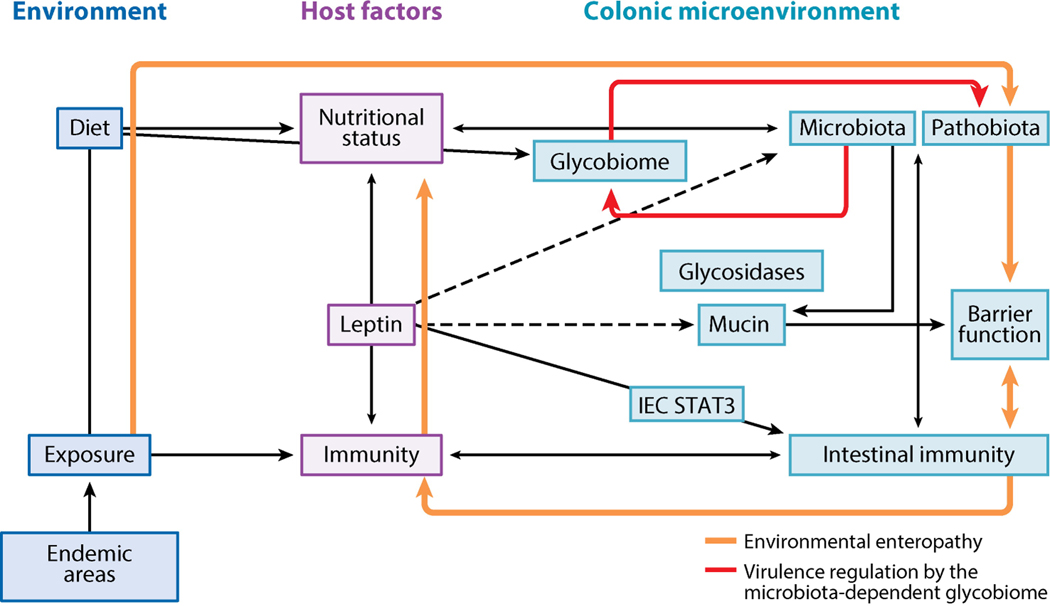

The vicious cycle of enteric infection and malnutrition. E. histolytica cysts enter the host via fecally contaminated food and water. In areas where E. histolytica infection is endemic, amoebic infection is pervasive and accompanied by multiple other enteric pathogens. The linked immune and nutritional status of the host determines whether infections will be resolved or established in the host intestine. Leptin levels regulate the immunodeficiency of malnutrition, and reduced leptin increases susceptibility to E. histolytica and other pathogens. Leptin signaling is critical for protection from E. histolytica at the intestinal epithelium. In the absence of immune clearance or treatment, E. histolytica and other enteric pathogens establish chronic infection as part of the pathobiota. The pathobiota causes chronic intestinal inflammation and mucus depletion. Chronic inflammatory responses disrupt the absorptive and barrier functions of the intestine, worsening malnutrition and leading to environmental enteropathy. E. histolytica causes dysbiosis with potential consequences for host nutrition and immunity, as the microbiota mediates intestinal immune homeostasis and nutrient extraction. The microbiota stimulates antimicrobial peptide and mucin production by intestinal epithelial cells (IECs), leading to exclusion of pathogens. Microbial metabolism of dietary and host-derived carbohydrates is essential for host nutrient absorption and for microbial metabolism and leads to competitive exclusion of some enteric pathogens. Microbial metabolism of complex polysaccharides in the colon produces short-chain fatty acids and oligosaccharides, which are critical for host nutrition. E. histolytica encodes sugar transporters and glycosidase genes from prokaryotes, indicating that E. histolytica is capable of exploiting free sugars produced by microbial metabolism. The microbially derived glycobiome is also an emerging regulator of enteric pathogen virulence. Dashed lines are hypothetical.