Abstract

Beyond the wide use of tamoxifen in breast cancer chemotherapy due to its estrogen receptor antagonist activity, this drug is being assayed in repurposing strategies against a number of microbial infections. We conducted a literature search on the evidence related with tamoxifen activity in macrophages, since these immune cells participate as a first line-defense against pathogen invasion. Consistent data indicate the existence of estrogen receptor-independent targets of tamoxifen in macrophages that include lipid mediators and signaling pathways, such as NRF2 and caspase-1, which allow these cells to undergo phenotypic adaptation and potentiate the inflammatory response, without the induction of cell death. Thus, these lines of evidence suggest that the widespread antimicrobial activity of this drug can be ascribed, at least in part, to the potentiation of the host innate immunity. This widens our understanding of the pharmacological activity of tamoxifen with relevant therapeutic implications for infections and other clinical indications that may benefit from the immunomodulatory effects of this drug.

Keywords: tamoxifen, SERMs, macrophages, infections, drug repurposing

Introduction

Tamoxifen is widely used in the treatment of breast cancer for its anti-proliferative activity mediated by the inhibition of estrogen signaling (Patel and Bihani 2018). The decades-long clinical experience along with a favorable pharmacokinetic profile lead to tamoxifen exploitation against other proliferation-related pathologies, such as estrogen-unrelated cancer and microbial infections (Martinez de Dueñas et al., 2014; Montoya and Krysan 2018; Clifford et al., 2020; Su et al., 2021). These off-target indications pertain repurposing strategies that make use of drugs already on the market for other clinical indications, in order to meet the urgent need of novel therapeutics without the expensive and long lasting process of drug discovery (Gil-Gil et al., 2019; Rana et al., 2019; Sharma et al., 2020); of interest to this review is the use of tamoxifen to overcome antimicrobial drug resistance and fight against new infectious diseases.

Beyond estrogen interference and antiproliferative activity, mounting evidence highlight molecular and cellular responses that implicate the involvement of host immune cells. Since macrophages are key immune cells in the fight against cancer and pathogen invasion (Sica et al., 2015), using “tamoxifen” AND “macrophages”, “immunity”, “off-target effects”, “infections”, “repurposing” as keywords, we conducted a systematic search through the PubMed electronic database of all types of studies and collected evidence, according to scientific impact and clinical relevance, on the immunomodulatory activity of tamoxifen in macrophages and infections.

Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms of Tamoxifen Action

On and Off-Targets

Orally administered tamoxifen undergoes hepatic conversion into active metabolites, such as 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4HT), that compete with the endogenous sex steroid hormones, estrogens, for binding to intracellular receptors, estrogen receptor alpha (ERα) and beta (ERβ). In fact, 4HT interacts with ERs with a similar binding affinity as the endogenous estrogen, 17β-estradiol (E2), whereas the prodrug shows a 100-fold lower affinity than 4HT (Rich et al., 2002). ERs are transcription factors that undergo conformational modifications, upon estrogen binding, that induce the receptor to interact with DNA elements within target gene promoters and transcriptional coregulators. Rapid cytoplasmic responses may also be induced by ERs or by estrogen binding to a membrane associated receptor, the G protein-coupled estrogen receptor (GPER), to which 4HT binds with a 1.000-fold lower affinity than ERs (Prossnitz and Arterburn 2015).

Tamoxifen and other ER ligands are defined as selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs), in that they induce tissue-selective ER agonist or antagonist effects depending on the interaction with tissue-selective transcriptional coregulators that are recruited by each ligand-specific receptor conformation (McDonnell et al., 2021). As a result, tamoxifen is clinically used in ERα-positive breast cancers as an antagonist of estrogen signaling in mammary epithelial cells, yet it provides secondary ERα-agonist effects in bone, preventing osteoporosis (Rachner et al., 2018), and in endometrium, leading to an increased risk of endometrial cancer (Braun, Overbeek-Wager, and Grumbo 2016).

Importantly, compelling evidence points to “off-target” responses to the prodrug, tamoxifen, which are mediated by ERα-unrelated, low-affinity effectors described in various cell lineages and physio-pathological conditions. Candidate mediators include PKC (protein kinase C), the transcription factors PPARγ (peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma), GR (glucocorticoid receptor), STAT1 (signal transducer and activator of transcription 1) and NRF2 (nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2) as well as other undefined targets that regulate calcium homeostasis or lipid and sphingolipid metabolism (Mésange et al., 2002; Kim et al., 2008; Matsuoka et al., 2009; Jiang et al., 2013; Bekele et al., 2016; Feng et al., 2017; Hasegawa et al., 2018; Govindarajah et al., 2019; Clifford et al., 2020).

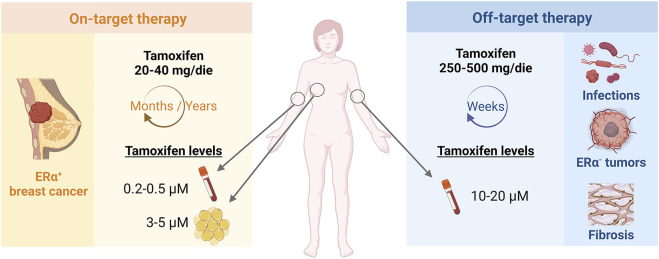

In clinical practice, the existence of on and off-biological targets translates into distinct tamoxifen therapeutic regimens according to the clinical indication (Figure 1). In the case of ERα-positive breast cancer, tamoxifen is prescribed at the daily dose of 20–40 mg/die for years-long treatments. On the other hand, 250–500 mg/die and short-term therapies are prescribed in ERα-independent conditions, such as microbial infections or other ERα-negative oncological or fibrotic diseases (Skapek et al., 2013; Odia et al., 2015; Quast et al., 2016; Ngan et al., 2019). Thus, micromolar concentrations of tamoxifen are reached within the tumour mass, as consequence of drug accumulation in the mammary adipose tissue with chronic low-dose regimens, and in the blood of patients undergoing short-term tamoxifen therapy for ERα-independent conditions (Trump et al., 1992; Kisanga et al., 2004; MacCallum et al., 2000). In other words, both chronic and acute pharmacological settings provide high tamoxifen concentrations that supposedly engage low-affinity molecular targets to accomplish the overall therapeutic success.

FIGURE 1.

Tamoxifen therapeutic regimen according to on- or off-target indications. Tamoxifen is administered at different concentrations and timings according to on-target, ERα-dependent or off-target, ERα-unrelated indications and may reach micromolar drug concentrations in patient plasma or tissues.

Antiproliferative and Oxidative Stress Responses

Cell toxicity induced by high tamoxifen concentrations was originally observed in epithelial cells and associated with inhibition of cell proliferation and induction of apoptosis by estrogen-independent mechanisms, later extended also to non-epithelial cells, such as hepatocytes, fibroblasts and retinal cells (Cho et al., 2012; Yokoyama et al., 2018). These observations led to exploit tamoxifen-induced cytotoxicity in ERα-negative cancers, as well as in infections, envisioning a direct pathogen-killing effect of the drug, and fibrosis, for tamoxifen inhibitory effect on proliferation and activity of renal and peritoneal fibroblasts (Vaglio et al., 2006; Dellê et al., 2012; Ma et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2018).

The mechanism of action of tamoxifen cytotoxicity when used at concentrations above the nanomolar range has been linked to the induction of oxidative stress, through the engagement of ERα-unrelated, undefined mediators that activate oxidative enzymes or modulate Ca2+ homeostasis, increasing the intracellular levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) or oxidized molecules (Lee et al., 2000; Nazarewicz et al., 2007). Recent molecular studies ascribed tamoxifen responses to the activation of the redox sensitive molecule NRF2, a transcription factor that regulates the expression of antioxidant proteins and promotes cell survival, with interesting implications for antineoplastic drug resistance mechanisms (Itoh et al., 1999; Kim et al., 2008; Bekele et al., 2016). Consistent evidence also indicates activation of inflammasomes and caspases as toxic responses to tamoxifen mediated by oxidative damage and subsequent activation of autophagy and cell apoptosis (Bowie et al., 2004; Cho et al., 2012).

The Antimicrobial Activity of Tamoxifen

Tamoxifen is effective against a broad range of life-threatening infections. As reported in Table 1, compelling evidence shows that tamoxifen counteracts the proliferation of bacterial species, a wide spectrum of fungal pathogens, human parasites and viruses, including the recently emerged species like Ebola, SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 viruses (Dyall et al., 2014; Fan et al., 2017; Montoya and Krysan 2018; Imamura et al., 2021; Zu et al., 2021; Allegretti et al., 2022).

TABLE 1.

Antimicrobial activity of Tamoxifen.

| Type of Study | Pathogen | Experimental Model | Tamoxifen Dosage | Tamoxifen Activity | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In vitro | L. amazonensis | Peritoneal macrophages | 5–20 µM | Alkalinization of intracellular vacuoles and suppression of parasite infection | Miguel et al. (2007) |

| HCV | Huh-7 cells | 1 µM | Suppression of viral genome replication | Watashi et al. (2007) | |

| Candida C. neoformans | Yeast cells | 32–64 μg/ml | Disruption of calmodulin-related processes and cell integrity | Dolan et al. (2009) | |

| S. cerevisiae | |||||

| L. braziliensis L. chagasi | BMDMs | 1–9 µM | Abrogation of intracellular infection | Miguel et al. (2009) | |

| EBOV | VERO E6, HepG2 cells | 1–10 µM | Potent inhibition of viral infection | Johansen et al. (2013) | |

| HCV | Huh-7 cells | 0,1–10 µM | Inhibition of multiple steps of viral life cycle | Murakami et al. (2013) | |

| C. neoformans | J774 macrophage-like cells | 8 μg/ml | Reduced viability within macrophages | Butts et al. (2014) | |

| MERS-CoV | VERO E6 cells | 0,1–100 µM | Antiviral effect observed by drug screening | Dyall et al. (2014) | |

| SARS-CoV | |||||

| M. tubercolosis | RAW 264.7 | 3–12 μg/ml | Reduced viability within macrophages | Jang et al. (2015) | |

| EBOV | HepG2, Hela, HEK293T cells | 1–15 µM | Cholesterol and Ca2+ accumulation, cellular sphingosine reduction and viral infection inhibition | Fan et al. (2017) | |

| P. falciparum | Parasite culture | 10 µM | Substantial changes in sphingolipid biosynthesis | Piňero et al. (2018) | |

| C. neoformans C. gattii | Fungal isolates | 2–16 μg/ml | Anti-cryptococcal effect alone and in combination with amphotericin | Hai et al. (2019) | |

| EBOV-like virus | Hela cells | 0,1–100 µM | Interference with viral infection through Ca2+ channel blockade | Penny et al. (2019) | |

| EBOV ASFV | VERO E6 cells | 10 µM | Inhibition of Ca2+ channels, accumulation of cholesterol and inhibition of viral infection | Galindo et al. (2021) | |

| SARS-CoV-2 | |||||

| SARS-CoV-2 | VERO E6 cells | 10 µM | Inhibitory effect on viral infection | Imamura et al. (2021) | |

| SARS-CoV-2 | VERO E6, Caco-2 cells | 1–10 µM | Reduction of S protein production | Zu et al. (2021) | |

| In vivo | Candida | Mouse | 200 mg/kg/day, 7 days, o.g | Decrease of kidney fungal burden | Dolan et al. (2009) |

| Leishmania | Mouse, hamster | 20 mg/kg/day, 15 days, i.p | Reduction of parasite burden | Miguel et al. (2009) | |

| C. neoformans | Mouse | 200 mg/kg/day, 3 days, o.g | Improvement of fluconazole anti-cryptococcal activity | Butts et al. (2014) | |

| SARS-CoV-2 | Mouse | 60 mg/kg/day, 3 days, i.p | Inhibition of viral RNA loads and inflammatory response | Zu et al. (2021) | |

| Clinical studies | L. braziliensis | Patients with cutaneous leishmaniasis | 40 mg/day, orally | Improvement of cure rates in combination with standard treatment for leishmaniasis | Machado et al. (2018) |

| 0.1% cream, topic use | |||||

| 20 days | |||||

| C. neoformans | Patients treated with fluconazole and amphotericin B | 300 mg/day, orally | Potential synergistic effect with classic antifungal drugs | Ngan et al. (2019) |

Summary of evidence on tamoxifen efficacy against a wide spectrum of pathogens.Legend: L. amazonensis/braziliensis/chagasi, Leishmania; HCV, Hepatitis C Virus; C. neoformans/gattii, Cryptococcus; S. cerevisae, Saccharomyces; BMDMs, Bone Marrow-derived Macrophages; EBOV, Ebola Virus; MERS-CoV, Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus; SARS-CoV(-2), Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (2); P. falciparum, Plasmodium; ASFV, African Swine Fever Virus; o.g., oral gavage; i.p., intraperitoneally.

Importantly, specific pharmacological features of tamoxifen, mainly its safety profile associated with only mild side effects, oral bioavailability and wide tissue distribution, make a short-term administration of tamoxifen more desirable as opposed to classical anti-infective agents, such as the antifungal fluconazole and amphotericin B, endowed with scarce diffusion and a high degree of toxicity (Butts et al., 2014; Hai et al., 2019; Ngan et al., 2019).

Some pathogen-specific targets have been proposed for tamoxifen antimicrobial activity, such as the calmodulin-dependent signaling pathway in yeast and bacterial cells, the sphingolipid biosynthesis in parasites or viral life cycle proteins (Watashi et al., 2007; Dolan et al., 2009; Murakami et al., 2013; Butts et al., 2014; Piñero et al., 2018). Yet, the wide spectrum of antimicrobial activity of this drug hints to a host-mediated protective system able to kill microbial cells, namely innate immunity. Surprisingly, the activity of tamoxifen has been scarcely investigated in innate immune cells, like macrophages, despite the clinical and pharmacological implications of this mechanism of action.

Tamoxifen Action Against Enveloped Viruses

Studies on enveloped viruses provided clear evidence for host-mediated, anti-infective actions of tamoxifen and insights into the molecular mechanisms that might also pertain a wider spectrum of anti-microbial activities. Enveloped viruses are endowed with a lipid coating, made of virus-encoded proteins and host-derived lipid membranes. These viral proteins allow the interaction with specific plasma membrane receptors and viral entry within host cells, where viruses are processed from early to late endosomal and, eventually, lysosomal pathways. However, in productive infections, the concerted action of endolysosomal enzymes, ion channels and sphingolipids metabolism increases the outflow of calcium ions and the redistribution of cholesterol, inducing structural changes in the viral and host endolysosomal membranes that merge to form a pore through which the viral genome can access to the cellular sites where replication begins (Mercer et al., 2020).

Tamoxifen and other SERMs are able to inhibit the infections of epithelial cells driven by enveloped viruses, such as Ebola and Hepatitis C virus, without affecting viral entry or endolysosome acidification, but interfering with steps of the viral life cycle that occur after binding and internalization (Johansen et al., 2013; Murakami et al., 2013). Drug responses were shown to be independent from ERs, yet the underlying mechanism of action is still unclear. It is known that SERMs act similarly to other drugs, called cationic amphiphilic drugs (CADs). Due to their lipophilic structures, CADs insert in phospholipid bilayers, particularly endolysosomal membranes where their hydrophilic heads become increasingly protonated by the low endosomal pH. As ionized forms, CADs cannot leave endolysosomes and accumulate up to levels that disturb the metabolism and transport of lipids and proteins (Breiden and Sandhoff 2019). Endosomal ceramide metabolism plays a key role in viral infections, with sphingosine formation that increases calcium efflux and induces the fusion of viral-host membranes. Ceramide metabolism takes place within endosomal lipid rafts, which are microdomains enriched with proteins that regulate signal transduction and other cellular functions, that may also represent druggable targets. Accumulation and interactions of CADs within lipid rafts cause the reduction of cellular sphingosine and increase in endo-lysosomal calcium and cholesterol levels, hindering viral genome exit. Therefore, CADs have been proposed as promising drugs for inhibiting viral infections (Salata et al., 2017). Importantly, tamoxifen activity against viral infections, such as Ebola or SARS-CoV-2 infections, has been associated with inhibition of sphingolipid metabolism and alterations in endosomal calcium and cholesterol traffic (Fan et al., 2017; Penny et al., 2019; Galindo et al., 2021). The increase in ceramide formation and reduction of sphingosine levels by tamoxifen has been also widely described in cancer cells (Furlong, Mader, and Hoskin 2006; Chapman et al., 2010; Morad et al., 2013). The underlying mechanism, although still poorly defined, has been reconciled with inhibition of the acid ceramidase enzyme, by cathepsin-mediated proteolysis, and prevention of ceramide glycosylation (Morad and Cabot 2015).

Macrophages as Cellular Targets of Tamoxifen

The immune activity of tamoxifen has received little attention so far, although the changes in abundance and function of immune cells, reported in clinical studies with tamoxifen, could participate in drug efficacy (Behjati and Frank 2009).

Macrophages are immune cells mainly committed to the orchestration of inflammation and immune responses. By recognizing a limitless number of physio-pathological signals, macrophages rapidly acquire distinct immune phenotypes defined within two activation states, the classical, pro-inflammatory M1 and the alternative, anti-inflammatory M2 phenotypes. These represent two hypothetical and simplistic extremes of a broad spectrum of intermediate phenotypes acquired by these cells, under the influence of the microenvironment (Locati, Curtale, and Mantovani 2020). M1 activation, as induced by viral and bacterial infections, is characterized by the production of ROS and proinflammatory mediators, such as IL-1β (interleukin one beta), TNF-α (tumor necrosis factor alpha) and IL-6 (interleukin 6), which provide a robust microbe-killing activity (Shapouri-Moghaddam et al., 2018). Anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages are activated by Th2 cytokines, produce signals that promote tissue repair, and actively suppress inflammation (Mantovani and Locati 2013).

Macrophage On and Off-Targets and Responses

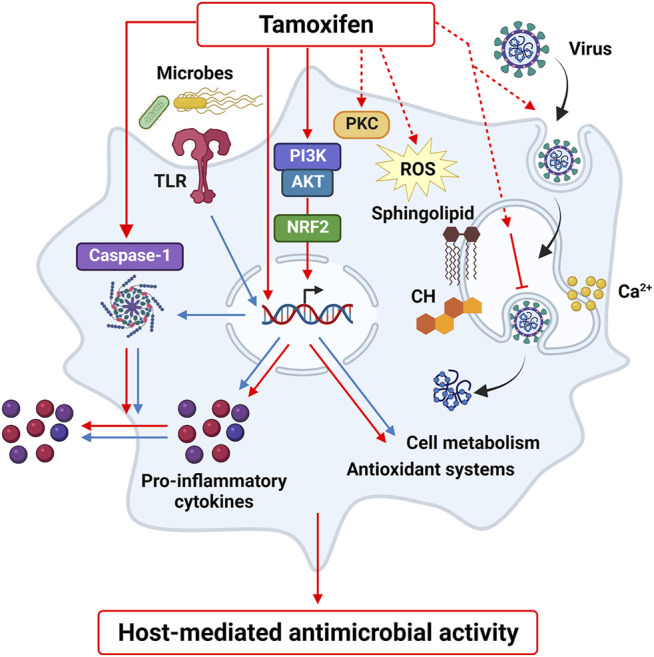

It has been shown that GPER and ERβ do not mediate the off-target macrophage responses to tamoxifen, since macrophages do not express ERβ and GPER-selective activation elicits different responses as those induced by tamoxifen. Instead, the ERα-mediated effects of E2 were inhibited by tamoxifen when assayed at 100-fold higher concentrations than nanomolar levels of the physiologic ligand, providing evidence for being an estrogen antagonist in innate immune cells (Pepe et al., 2018, 2021). Importantly, also ERα-independent responses were identified when using micromolar concentrations of tamoxifen. The molecular mechanism of tamoxifen activity in macrophages was initially associated with the activation of PKC and transcription factors, such as GR, PPARy and STAT1 (Komi et al., 2001; Jiang et al., 2013). More recently, the PI3K (phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase)/AKT pathway and NRF2 activation have also been proposed as additional immune targets of tamoxifen, increasing the expression of NRF2 target genes, such as Hmox-1 (heme oxygenase 1), or Vegf-a (vascular endothelial growth factor A) and inhibiting other immune polarization markers such as Il-1b or Arg-1 (arginase 1) (Feng et al., 2018; Pepe et al., 2021). This finding is particularly interesting, considering that NRF2 activation in macrophages prompts protective responses against infections through phagocytosis and autophagy of bacterial or viral particles, induction of intracellular detoxification reactions and potentiation of the inflammatory response (Hai et al., 2011; Harvey et al., 2011; Mornata et al., 2020; Furuya et al., 2016; Bewley et al., 2018; Zhao et al., 2014).

Differently from cytotoxicity in epithelial or hepatic cells, off-target effects of tamoxifen do not induce macrophage cell death. Earlier studies reported the influence of tamoxifen on cholesterol homeostasis and lipid metabolism of macrophages, supporting the beneficial consequences of this drug against foam cells formation and atherosclerosis (Dong et al., 2011; Fernández-Suárez et al., 2016; Jiang et al., 2013; Yu et al., 2016). Notably, drug activity in macrophages has been recently extended to immune-metabolic responses. In fact, tamoxifen was shown to potentiate the M1 phenotype, increase phagocytosis and induce active caspase-1 formation (Pepe et al., 2021). Transformation of caspase-1 precursor into the active enzyme promotes IL-1β maturation and secretion by macrophages, thus controlling pathogen infections (Man, Karki, and Kanneganti 2017). Caspase-1 activation may eventually associate with cell death programs; however, IL-1β secretion can occur also independently from cell lysis (Evavold et al., 2018). This latter mechanism has been observed for tamoxifen, which induces active caspase-1 formation in macrophages without affecting cell viability (Pepe et al., 2021). A summary of the possible targets proposed by molecular and cellular studies for tamoxifen activity in macrophages is reported in Figure 2. Whether this immunoregulatory activity underlies the widespread antimicrobial effects of tamoxifen is still unknown. Some data report the efficacy of this drug against the growth of pathogens that, interestingly, proliferate inside macrophages, as in the case of Salmonella, Mycobacteria spp and Cryptococcus neoformans (Miguel et al., 2009; Butts et al., 2014; Jang et al., 2015; Lim et al., 2018; Hai et al., 2019; Ngan et al., 2019). Tamoxifen was shown to modify the pH on intracellular vacuoles in infected macrophages, with a beneficial effect in controlling the infection by intracellular parasites such as Leishmania. (Miguel et al., 2007). This suggests that the immunomodulatory effects of this drug in macrophages may provide antimicrobial effects in parallel with a direct antiproliferative activity in microbes.

FIGURE 2.

Tamoxifen off-target effects in macrophages. Tamoxifen regulates macrophage activation by inducing PI3K-NRF2 pathway, caspase-1 formation and by modulating lipid metabolism and calcium homeostasis, as well as other possible targets identified in other cell types, such as PKC and oxidative stress. These molecular mediators and cell responses may represent a host-mediated mechanism that contributes to the beneficial activity of tamoxifen against pathogen and viral infections.

Conclusion and Future Directions

Available data in the literature suggest that tamoxifen increases the ability of macrophages to activate an inflammatory response and generate a hostile environment for invading microbes. Although still preliminary, these cellular and molecular responses are triggered by concentrations of tamoxifen that are ensured in the clinical practice by therapeutic regimens that use higher, yet safe and well tolerated, dosages than those used in breast cancer (Skapek et al., 2013; Odia et al., 2015; Ngan et al., 2019). These data strongly support the hypothesis that the immune-mediated effects of tamoxifen contribute to the efficacy of this drug against a wide spectrum of pathogen infections and sustain tamoxifen repurposing in infectious diseases, alone or in combination with standard treatments (Machado et al., 2018; Ngan et al., 2019; Ribeiro et al., 2021).

Importantly, some specific mediators of the off-target effects of tamoxifen have been identified, such as NRF2 signaling, caspase-1 activation and cholesterol redistribution. These pathways are known to control macrophage immunometabolism and inflammatory responses, thus being essential in containing infections. Moreover, tamoxifen was shown to induce neuroprotective effects by regulating microglia activation, further expanding the tissue distribution of drug immune activity (Barreto, Santos-Galindo, and Garcia-Segura 2014; Wu et al., 2021). Therefore, further studies are needed not only to upraise the clinical relevance of tamoxifen activity in macrophages but also to advance target identification and drug development in order to improve therapeutic options. Indeed, the wide availability of drugs like tamoxifen that easily permeate host immune cells, where they trigger beneficial responses, represents a therapeutic advantage for an extensive spectrum of infections, particularly against multidrug-resistant pathogens, where classical therapeutic agents fail, or when infections are driven by intracellular microbes that survive within macrophages. Finally, beyond anti-infective strategies in which tamoxifen repurposing has already proved its efficacy, exploitation of host-mediated responses to tamoxifen will possibly lead to substantial advancement in therapeutic approaches of other proliferation-related pathologies, such as oncological or fibrotic diseases.

Author Contributions

CS, GP, AD, SDT, MCC, MA, ML, and EV contributed to the writing of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Ministero della Salute (COVID-2020-12371849) and University of Milan through the APC initiative.

Conflict of Interest

MCC and MA were employed by Dompé Farmaceutici S.p.A.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- Allegretti M., Cesta M. C., Zippoli M., Beccari A., Talarico C., Mantelli F., et al. (2022). Repurposing the Estrogen Receptor Modulator Raloxifene to Treat SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Cell Death Differ 29 (1), 156–166. 10.1038/s41418-021-00844-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barreto G. E., Santos-Galindo M., Garcia-Segura L. M. (2014). Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators Regulate Reactive Microglia after Penetrating Brain Injury. Front. Aging Neurosci. 6, 132. 10.3389/fnagi.2014.00132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bekele R. T., Venkatraman G., Liu R. Z., Tang X., Mi S., Benesch M. G., et al. (2016). Oxidative Stress Contributes to the Tamoxifen-Induced Killing of Breast Cancer Cells: Implications for Tamoxifen Therapy and Resistance. Sci. Rep. 6, 21164. 10.1038/srep21164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bewley M. A., Budd R. C., Ryan E., Cole J., Collini P., Marshall J., et al. (2018). Opsonic Phagocytosis in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Is Enhanced by Nrf2 Agonists. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 198 (6), 739–750. 10.1164/rccm.201705-0903OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowie M. L., Dietze E. C., Delrow J., Bean G. R., Troch M. M., Marjoram R. J., et al. (2004). Interferon-Regulatory Factor-1 Is Critical for Tamoxifen-Mediated Apoptosis in Human Mammary Epithelial Cells. Oncogene 23 (54), 8743–8755. 10.1038/sj.onc.1208120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun M. M., Overbeek-Wager E. A., Grumbo R. J. (2016). Diagnosis and Management of Endometrial Cancer. Am. Fam. Physician 93 (6), 468–474. www.aafp.org/afp. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breiden B., Sandhoff K. (2019). Emerging Mechanisms of Drug-Induced Phospholipidosis. Biol. Chem. 401 (1), 31–46. 10.1515/hsz-2019-0270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butts A., Koselny K., Chabrier-Roselló Y., Semighini C. P., Brown J. C., Wang X., et al. (2014). Estrogen Receptor Antagonists Are Anti-cryptococcal Agents that Directly Bind EF Hand Proteins and Synergize with Fluconazole In Vivo . mBio 5 (1), e00765–13. 10.1128/mBio.00765-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman J. V., Gouazé-Andersson V., Messner M. C., Flowers M., Karimi R., Kester M., et al. (2010). Metabolism of Short-Chain Ceramide by Human Cancer Cells--Implications for Therapeutic Approaches. Biochem. Pharmacol. 80 (3), 308–315. 10.1016/j.bcp.2010.04.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho K. S., Yoon Y. H., Choi J. A., Lee S.-J., Koh J.-Y. (2012). Induction of Autophagy and Cell Death by Tamoxifen in Cultured Retinal Pigment Epithelial and Photoreceptor Cells. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 53 (9), 5344–5353. 10.1167/iovs.12-9827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clifford R. E., Bowden D., Blower E., Kirwan C. C., Vimalachandran D. (2020). Does Tamoxifen Have a Therapeutic Role outside of Breast Cancer? A Systematic Review of the Evidence. Surg. Oncol. 33, 100–107. 10.1016/j.suronc.2020.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dellê H., Rocha J. R., Cavaglieri R. C., Vieira J. M., Jr, Malheiros D. M., Noronha I. L. (2012). Antifibrotic Effect of Tamoxifen in a Model of Progressive Renal Disease. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 23, 37–48. 10.1681/ASN.2011010046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolan K., Montgomery S., Buchheit B., Didone L., Wellington M., Krysan D. J. (2009). Antifungal Activity of Tamoxifen: In Vitro and In Vivo Activities and Mechanistic Characterization. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53 (8), 3337–3346. 10.1128/AAC.01564-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong P., Xie T., Zhou X., Hu W., Chen Y., Duan Y., et al. (2011). Induction of Macrophage Scavenger Receptor Type BI Expression by Tamoxifen and 4-Hydroxytamoxifen. Atherosclerosis 218 (2), 435–442. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.06.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyall J., Coleman C. M., Hart B. J., Venkataraman T., Holbrook M. R., Kindrachuk J., et al. (2014). Repurposing of Clinically Developed Drugs for Treatment of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Infection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 58 (8), 4885–4893. 10.1128/AAC.03036-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evavold C. L., Ruan J., Tan Y., Xia S., Wu H., Kagan J. C. (2018). The Pore-Forming Protein Gasdermin D Regulates Interleukin-1 Secretion from Living Macrophages. Immunity 48 (1), 35–e6. e6. 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.11.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan H., Du X., Zhang J., Zheng H., Lu X., Wu Q., et al. (2017). Selective Inhibition of Ebola Entry with Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators by Disrupting the Endolysosomal Calcium. Sci. Rep. 7, 41226. 10.1038/srep41226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng L., Li J., Yang L., Zhu L., Huang X., Zhang S., et al. (2017). Tamoxifen Activates Nrf2-dependent SQSTM1 Transcription to Promote Endometrial Hyperplasia. Theranostics 7 (7), 1890–1900. 10.7150/thno.19135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng R., Morine Y., Ikemoto T., Imura S., Iwahashi S., Saito Y., et al. (2018). Nrf2 Activation Drive Macrophages Polarization and Cancer Cell Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition during Interaction. Cell Commun Signal 16 (1), 54. 10.1186/s12964-018-0262-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Suárez M. E., Escolà-Gil J. C., Pastor O., Dávalos A., Blanco-Vaca F., Lasunción M. A., et al. (2016). Clinically Used Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators Affect Different Steps of Macrophage-specific Reverse Cholesterol Transport. Sci. Rep. 6, 32105. 10.1038/srep32105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furlong S. J., Mader J. S., Hoskin D. W. (2006). Lactoferricin-Induced Apoptosis in Estrogen-Nonresponsive MDA-MB-435 Breast Cancer Cells Is Enhanced by C6 Ceramide or Tamoxifen. Oncol. Rep. 15 (5), 1385–1390. 10.3892/or.15.5.1385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuya A. K., Sharifi H. J., Jellinger R. M., Cristofano P., Shi B., de Noronha C. M. (2016). Sulforaphane Inhibits HIV Infection of Macrophages through Nrf2. Plos Pathog. 12 (4), e1005581. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galindo I., Garaigorta U., Lasala F., Cuesta-Geijo M. A., Bueno P., Gil C., et al. (2021). Antiviral Drugs Targeting Endosomal Membrane Proteins Inhibit Distant Animal and Human Pathogenic Viruses. Antivir. Res 186, 104990. 10.1016/j.antiviral.2020.104990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil-Gil T., Laborda P., Sanz-García F., Hernando-Amado S., Blanco P., Martínez J. L. (2019). Antimicrobial Resistance: A Multifaceted Problem with Multipronged Solutions. MicrobiologyOpen 8 (11), e945. 10.1002/mbo3.945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govindarajah N., Clifford R., Bowden D., Sutton P. A., Parsons J. L., Vimalachandran D. (2019). Sphingolipids and Acid Ceramidase as Therapeutic Targets in Cancer Therapy. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 138, 104–111. 10.1002/mbo3.94510.1016/j.critrevonc.2019.03.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hai T. P., Van A. D., Ngan N., Nhat L., Lan N., Vinh Chau N. V., et al. (2011). Targeting Nrf2 Signaling Improves Bacterial Clearance by Alveolar Macrophages in Patients with COPD and in a Mouse Model. Sci. Transl. Med. 3 (78), 78ra32. 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hai T. P., Van A. D., Ngan N. T. T., Nhat L. T. H., Lan N. P. H., Vinh Chau N. V., et al. (2019). The Combination of Tamoxifen with Amphotericin B, but Not with Fluconazole, Has Synergistic Activity against the Majority of Clinical Isolates of Cryptococcus Neoformans. Mycoses 62 (9), 818–825. 10.1111/myc.12955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey C. J., Thimmulappa R. K., Sethi S., Kong X., Yarmus L., Brown R. H., et al. (2011). Targeting Nrf2 Signaling Improves Bacterial Clearance by Alveolar Macrophages in Patients with COPD and in a Mouse Model. Sci. Transl. Med. 3 (78), 78ra32. 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa G., Akatsuka K., Nakashima Y., Yokoe Y., Higo N., Shimonaka M. (2018). Tamoxifen Inhibits the Proliferation of Non-melanoma S-kin C-ancer C-ells by I-ncreasing I-ntracellular C-alcium C-oncentration. Int. J. Oncol. 53 (5), 2157–2166. 10.3892/ijo.2018.4548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imamura K., Sakurai Y., Enami T., Shibukawa R., Nishi Y., Ohta A., et al. (2021). IPSC Screening for Drug Repurposing Identifies Anti-RNA Virus Agents Modulating Host Cell Susceptibility. FEBS open bio 11 (5), 1452–1464. 10.1002/2211-5463.13153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh K., Wakabayashi N., Katoh Y., Ishii T., Igarashi K., Engel J. D., et al. (1999). Keap1 Represses Nuclear Activation of Antioxidant Responsive Elements by Nrf2 through Binding to the Amino-Terminal Neh2 Domain. Genes Dev. 13 (1), 76–86. 10.1101/gad.13.1.76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang W. S., Kim S., Podder B., Jyoti M. A., Nam K. W., Lee B. E., et al. (2015). Anti-Mycobacterial Activity of Tamoxifen against Drug-Resistant and Intra-macrophage Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 25 (6), 946–950. 10.4014/jmb.1412.12023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang M., Zhang L., Ma X., Hu W., Chen Y., Yu M., et al. (2013). Tamoxifen Inhibits Macrophage FABP4 Expression through the Combined Effects of the GR and PPARγ Pathways. Biochem. J. 454 (3), 467–477. 10.1042/BJ20130580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansen L. M., Brannan J. M., Delos S. E., Shoemaker C. J., Stossel A., Lear C., et al. (2013). FDA-approved Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators Inhibit Ebola Virus Infection. Sci. Transl Med. 5 (190), 190ra79. 10.1126/scitranslmed.3005471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S. K., Yang J. W., Kim M. R., Roh S. H., Kim H. G., Lee K. Y., et al. (2008). Increased Expression of Nrf2/ARE-dependent Anti-oxidant Proteins in Tamoxifen-Resistant Breast Cancer Cells. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 45 (4), 537–546. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kisanga E. R., Gjerde J., Guerrieri-Gonzaga A., Pigatto F., Pesci-Feltri A., Robertson C., et al. (2004). Tamoxifen and Metabolite Concentrations in Serum and Breast Cancer Tissue during Three Dose Regimens in a Randomized Preoperative Trial. Clin. Cancer Res. 10 (7), 2336–2343. 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-03-0538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komi J., Möttönen M., Luukkainen R., Lassila O. (2001). Non-Steroidal Anti-oestrogens Inhibit the Differentiation of Synovial Macrophages into Dendritic Cells. Rheumatology (Oxford) 40 (2), 185–191. 10.1093/rheumatology/40.2.185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y. S., Kang Y. S., Lee S. H., Kim J. A. (2000). Role of NAD(P)H Oxidase in the Tamoxifen-Induced Generation of Reactive Oxygen Species and Apoptosis in HepG2 Human Hepatoblastoma Cells. Cel Death Differ 7 (10), 925–932. 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim D., Kim K. S., Jeong J. H., Marques O., Kim H. J., Song M., et al. (2018). The Hepcidin-Ferroportin axis Controls the Iron Content of Salmonella-Containing Vacuoles in Macrophages. Nat. Commun. 9 (1), 2091. 10.1038/s41467-018-04446-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locati M., Curtale G., Mantovani A. (2020). Diversity, Mechanisms, and Significance of Macrophage Plasticity. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 15, 123–147. 10.1146/annurev-pathmechdis-012418-012718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma G., He J., Yu Y., Xu Y., Yu X., Martinez J., et al. (2015). Tamoxifen Inhibits ER-Negative Breast Cancer Cell Invasion and Metastasis by Accelerating Twist1 Degradation. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 11 (5), 618–628. 10.7150/ijbs.11380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacCallum J., Cummings J., Dixon J. M., Miller W. R. (2000). Concentrations of Tamoxifen and its Major Metabolites in Hormone Responsive and Resistant Breast Tumours. Br. J. Cancer 82 (10), 1629–1635. 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machado P. R. L., Ribeiro C. S., França-Costa J., Dourado M. E. F., Trinconi C. T., Yokoyama-Yasunaka J. K. U., et al. (2018). Tamoxifen and Meglumine Antimoniate Combined Therapy in Cutaneous Leishmaniasis Patients: a Randomised Trial. Trop. Med. Int. Health 23 (9), 936–942. 10.1111/tmi.13119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Man S. M., Karki R., Kanneganti T. D. (2017). Molecular Mechanisms and Functions of Pyroptosis, Inflammatory Caspases and Inflammasomes in Infectious Diseases. Immunol. Rev. 277 (1), 61–75. 10.1111/imr.12534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantovani A., Locati M. (2013). Tumor-Associated Macrophages as a Paradigm of Macrophage Plasticity, Diversity, and Polarization. Arterioscler Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 33 (7), 1478–1483. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.113.300168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez de Dueñas E., Ochoa Aranda E., Blancas Lopez-Barajas I., Ferrer Magdalena T., Bandrés Moya F., Chicharro García L. M., et al. (2014). Adjusting the Dose of Tamoxifen in Patients with Early Breast Cancer and CYP2D6 Poor Metabolizer Phenotype. Breast 23 (4), 400–406. 10.1016/j.breast.2014.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuoka H., Tsubaki M., Yamazoe Y., Ogaki M., Satou T., Itoh T., et al. (2009). Tamoxifen Inhibits Tumor Cell Invasion and Metastasis in Mouse Melanoma through Suppression of PKC/MEK/ERK and PKC/PI3K/Akt Pathways. Exp. Cel Res 315 (12), 2022–2032. 10.1016/j.yexcr.2009.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonnell D. P., Wardell S. E., Chang C.-Y., Norris J. D. (2021). Next-Generation Endocrine Therapies for Breast Cancer. Jco 39 (12), 1383–1388. 10.1200/JCO.20.03565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercer J., Lee J. E., Saphire E. O., Freeman S. A. (2020). SnapShot: Enveloped Virus Entry. Cell 182 (3), 786–e1. 10.1016/j.cell.2020.06.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mésange F., Sebbar M., Capdevielle J., Guillemot J. C., Ferrara P., Bayard F., et al. (2002). Identification of Two Tamoxifen Target Proteins by Photolabeling with 4-(2-Morpholinoethoxy)Benzophenone. Bioconjug. Chem. 13 (4), 766–772. 10.1021/bc015588t [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miguel D. C., Yokoyama-Yasunaka J. K., Andreoli W. K., Mortara R. A., Uliana S. R. (2007). Tamoxifen Is Effective against Leishmania and Induces a Rapid Alkalinization of Parasitophorous Vacuoles Harbouring Leishmania (Leishmania) Amazonensis Amastigotes. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 60 (3), 526–534. 10.1093/jac/dkm219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miguel D. C., Zauli-Nascimento R. C., Yokoyama-Yasunaka J. K., Katz S., Barbiéri C. L., Uliana S. R. (2009). Tamoxifen as a Potential Antileishmanial Agent: Efficacy in the Treatment of Leishmania Braziliensis and Leishmania Chagasi Infections. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 63 (2), 365–368. 10.1093/jac/dkn509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montoya M. C., Krysan D. J. (2018). Repurposing Estrogen Receptor Antagonists for the Treatment of Infectious Disease. mBio 9 (6), e02272–18. 10.1128/mBio.02272-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morad S. A., Cabot M. C. (2015). Tamoxifen Regulation of Sphingolipid Metabolism--Therapeutic Implications. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1851 (9), 1134–1145. 10.1016/j.bbalip.2015.05.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morad S. A., Madigan J. P., Levin J. C., Abdelmageed N., Karimi R., Rosenberg D. W., et al. (2013). Tamoxifen Magnifies Therapeutic Impact of Ceramide in Human Colorectal Cancer Cells Independent of P53. Biochem. Pharmacol. 85 (8), 1057–1065. 10.1016/j.bcp.2013.01.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mornata F., Pepe G., Sfogliarini C., Brunialti E., Rovati G., Locati M., et al. (2020). Reciprocal Interference between the NRF2 and LPS Signaling Pathways on the Immune-Metabolic Phenotype of Peritoneal Macrophages. Pharmacol. Res. Perspect. 8 (4), e00638. 10.1002/prp2.638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami Y., Fukasawa M., Kaneko Y., Suzuki T., Wakita T., Fukazawa H. (2013). Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators Inhibit Hepatitis C Virus Infection at Multiple Steps of the Virus Life Cycle. Microbes Infect. 15 (1), 45–55. 10.1016/j.micinf.2012.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nazarewicz R. R., Zenebe W. J., Parihar A., Larson S. K., Alidema E., Choi J., et al. (2007). Tamoxifen Induces Oxidative Stress and Mitochondrial Apoptosis via Stimulating Mitochondrial Nitric Oxide Synthase. Cancer Res. 67 (3), 1282–1290. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngan N. T. T., Mai N. T. H., Tung N. L. N., Lan N. P. H., Tai L. T. H., Phu N. H., et al. (2019). A Randomized Open Label Trial of Tamoxifen Combined with Amphotericin B and Fluconazole for Cryptococcal Meningitis. Wellcome Open Res. 4, 8. 10.7554/eLife.6892910.12688/wellcomeopenres.15010.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odia Y., Kreisl T. N., Aregawi D., Innis E. K., Fine H. A. (2015). A Phase II Trial of Tamoxifen and Bortezomib in Patients with Recurrent Malignant Gliomas. J. Neurooncol. 125 (1), 191–195. 10.1007/s11060-015-1894-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel H. K., Bihani T. (2018). Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators (SERMs) and Selective Estrogen Receptor Degraders (SERDs) in Cancer Treatment. Pharmacol. Ther. 186, 1–24. 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2017.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penny C. J., Vassileva K., Jha A., Yuan Y., Chee X., Yates E., et al. (2019). Mining of Ebola Virus Entry Inhibitors Identifies Approved Drugs as Two-Pore Channel Pore Blockers. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cel Res 1866 (7), 1151–1161. 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2018.10.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pepe G., Locati M., Della Torre S., Mornata F., Cignarella A., Maggi A., et al. (2018). The Estrogen-Macrophage Interplay in the Homeostasis of the Female Reproductive Tract. Hum. Reprod. Update 24 (6), 652–672. 10.1093/humupd/dmy026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pepe G., Sfogliarini C., Rizzello L., Battaglia G., Pinna C., Rovati G., et al. (2021). Erα-independent NRF2-Mediated Immunoregulatory Activity of Tamoxifen. Biomed. Pharmacother. 144, 112274. 10.1016/j.biopha.2021.112274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piñero T. A., Landoni M., Duschak V. G., Katzin A. M., Couto A. S. (2018). Effect of Tamoxifen on the Sphingolipid Biosynthetic Pathway in the Different Intraerythrocytic Stages of the Apicomplexa Plasmodium Falciparum. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 497 (4), 1082–1088. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.02.183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prossnitz E. R., Arterburn J. B. (2015). International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. XCVII. G Protein-Coupled Estrogen Receptor and its Pharmacologic Modulators. Pharmacol. Rev. 67 (3), 505–540. 10.1124/pr.114.009712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quast D. R., Schneider R., Burdzik E., Hoppe S., Möslein G. (2016). Long-Term Outcome of Sporadic and FAP-Associated Desmoid Tumors Treated with High-Dose Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators and Sulindac: A Single-Center Long-Term Observational Study in 134 Patients. Fam. Cancer 15 (1), 31–40. 10.1007/s10689-015-9830-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rachner T. D., Coleman R., Hadji P., Hofbauer L. C. (2018). Bone Health during Endocrine Therapy for Cancer. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 6 (11), 901–910. 10.1016/S2213-8587(18)30047-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rana R., Sharma R., Kumar A. (2019). Repurposing of Existing Statin Drugs for Treatment of Microbial Infections: How Much Promising? Infect. Disord. Drug Targets 19 (3), 224–237. 10.2174/1871526518666180806123230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro C. S., França R. R., Silva J. A., Silva S. C. D., Uliana S. R. B., Boaventura V. S., et al. (2021). Cellular Infiltrate in Cutaneous Leishmaniasis Lesions and Therapeutic Outcome. Bras Dermatol. 96 (5), 544–550. 10.1016/j.abd.2021.02.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rich R. L., Hoth L. R., Geoghegan K. F., Brown T. A., LeMotte P. K., Simons S. P., et al. (2002). Kinetic Analysis of Estrogen Receptor/Ligand Interactions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 99 (13), 8562–8567. 10.1073/pnas.142288199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salata C., Calistri A., Parolin C., Baritussio A., Palù G. (2017). Antiviral Activity of Cationic Amphiphilic Drugs. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 15 (5), 483–492. 10.1080/14787210.2017.1305888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapouri-Moghaddam A., Mohammadian S., Vazini H., Taghadosi M., Esmaeili S. A., Mardani F., et al. (2018). Macrophage Plasticity, Polarization, and Function in Health and Disease. J. Cel Physiol 233 (9), 6425–6440. 10.1002/jcp.26429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sica A., Erreni M., Allavena P., Porta C. (2015). Macrophage Polarization in Pathology. Cell Mol Life Sci 72 (21), 4111–4126. 10.1007/s00018-015-1995-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skapek S. X., Anderson J. R., Hill D. A., Henry D., Spunt S. L., Meyer W., et al. (2013). Safety and Efficacy of High-Dose Tamoxifen and Sulindac for Desmoid Tumor in Children: Results of a Children's Oncology Group (COG) Phase II Study. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 60 (7), 1108–1112. 10.1002/pbc.24457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su Y., Zhang Y., Hua X., Huang J., Bi X., Xia W., Wang X., Huang Z., Song C., Zhong Y., Shi Y., Wang S., Fan W., Fan W., Yuan Z. South China Breast Cancer Group (SCBCG) (2021). High-Dose Tamoxifen in High-Hormone-Receptor-Expressing Advanced Breast Cancer Patients: A Phase II Pilot Study. Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol. 13, 1758835921993436. 10.1177/1758835921993436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaglio A., Salvarani C., Buzio C. (2006). Retroperitoneal Fibrosis. Lancet 367 (9506), 241–251. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68035-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S., Li X., Yan L., Nie Q., Dai J., Chen H., et al. (2018). Tamoxifen Inhibits Fibroblast Proliferation and Prevents Epidural Fibrosis by Regulating the AKT Pathway in Rats. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 497 (4), 937–942. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.01.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watashi K., Inoue D., Hijikata M., Goto K., Aly H. H., Shimotohno K. (2007). Anti-Hepatitis C Virus Activity of Tamoxifen Reveals the Functional Association of Estrogen Receptor with Viral RNA Polymerase NS5B. J. Biol. Chem. 282 (45), 32765–32772. 10.1074/jbc.M704418200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu S. Y., Sharma S., Wu K., Tyagi A., Zhao D., Deshpande R. P., et al. (2021). Tamoxifen Suppresses Brain Metastasis of Estrogen Receptor-Deficient Breast Cancer by Skewing Microglia Polarization and Enhancing Their Immune Functions. Breast Cancer Res. 23 (1), 35. 10.1186/s13058-021-01412-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokoyama Y., Sasaki Y., Terasaki N., Kawataki T., Takekawa K., Iwase Y., et al. (2018). Comparison of Drug Metabolism and its Related Hepatotoxic Effects in HepaRG, Cryopreserved Human Hepatocytes, and HepG2 Cell Cultures. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 41 (5), 722–732. 10.1248/bpb.b17-00913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu M., Jiang M., Chen Y., Zhang S., Zhang W., Yang X., et al. (2016). Inhibition of Macrophage CD36 Expression and Cellular Oxidized Low Density Lipoprotein (oxLDL) Accumulation by Tamoxifen: A Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor (Ppar)Γ-dependent Mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 291 (33), 16977–16989. 10.1074/jbc.M116.740092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao C., Gillette D. D., Li X., Zhang Z., Wen H. (2014). Nuclear Factor E2-Related Factor-2 (Nrf2) Is Required for NLRP3 and AIM2 Inflammasome Activation. J. Biol. Chem. 289 (24), 17020–17029. 10.1074/jbc.M114.563114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zu S., Luo D., Li L., Ye Q., Li R. T., Wang Y., et al. (2021). Tamoxifen and Clomiphene Inhibit SARS-CoV-2 Infection by Suppressing Viral Entry. Signal. Transduct Target. Ther. 6 (1), 435. 10.1038/s41392-021-00853-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]