Abstract

Background

Trauma and chronic stress are believed to induce and exacerbate psychopathology by disrupting glutamate synaptic strength. However, in vivo in human methods to estimate synaptic strength are limited. In this study, we established a novel putative biomarker of glutamatergic synaptic strength, termed energy-per-cycle (EPC). Then, we used EPC to investigate the role of prefrontal neurotransmission in trauma-related psychopathology.

Methods

Healthy controls (n = 18) and patients with posttraumatic stress (PTSD; n = 16) completed 13C-acetate magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) scans to estimate prefrontal EPC, which is the ratio of neuronal energetic needs per glutamate neurotransmission cycle (VTCA/VCycle).

Results

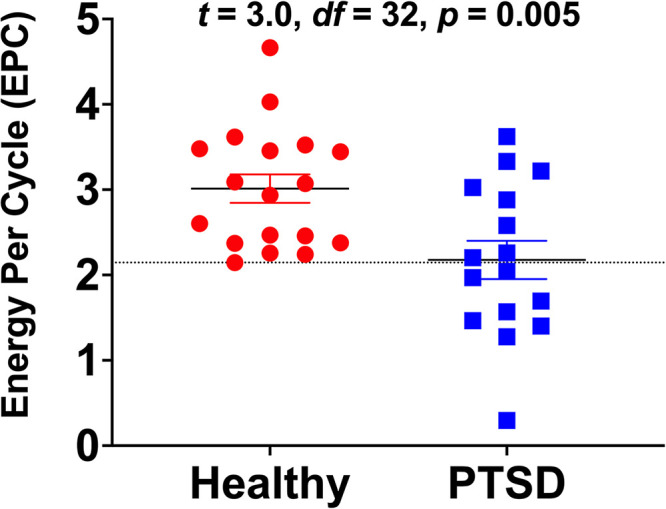

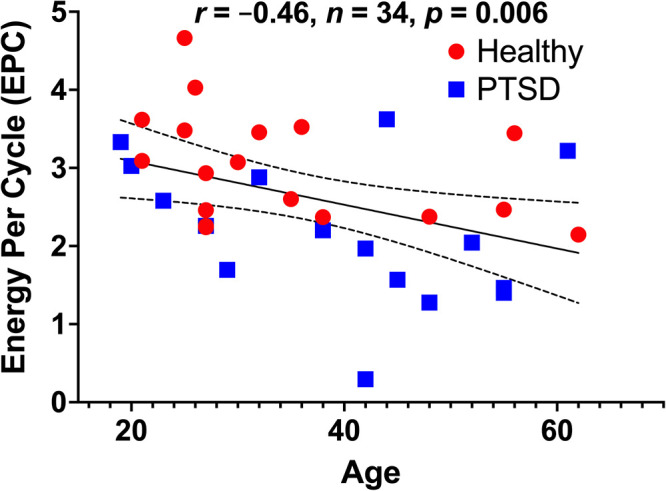

Patients with PTSD were found to have 28% reduction in prefrontal EPC (t = 3.0; df = 32, P = .005). There was no effect of sex on EPC, but age was negatively associated with prefrontal EPC across groups (r = –0.46, n = 34, P = .006). Controlling for age did not affect the study results.

Conclusion

The feasibility and utility of estimating prefrontal EPC using 13C-acetate MRS were established. Patients with PTSD were found to have reduced prefrontal glutamatergic synaptic strength. These findings suggest that reduced glutamatergic synaptic strength may contribute to the pathophysiology of PTSD and could be targeted by new treatments.

Keywords: PTSD, depression, glutamate, synaptic strength, stress, trauma

Introduction

Stressors, whether acutely overwhelming or chronic, may trigger or exacerbate posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). 1 While the neurobiology of trauma and stress is not fully known, 2 converging evidence suggests a critical role for glutamatergic synaptic connectivity alterations that produce the dysfunction of brain networks regulating memory and emotion associated with the PTSD symptoms.3–5 This hypothesis is emerging from many sources of data, including preclinical and postmortem data, and indirect human in vivo findings from gross brain structure, functional connectivity, total neurochemical levels, and various receptor binding potentials.4,6,7 Yet, a major obstacle in the field remains the lack of a more direct and dynamic assessment of glutamatergic synaptic strength in vivo in patients.

Here, we establish a novel metric of glutamate function that is believed to directly reflect glutamatergic synaptic strength. 8 Synaptic strength is defined as the magnitude of the postsynaptic response to a presynaptic action potential. Traditionally, changes in synaptic strength, such as long-term potentiation or long-term depression, are measured using electrophysiologic techniques. 9 However, considering the tight coupling between synaptic signaling and brain energetics, 10 it is possible to infer overall glutamatergic synaptic strength within a brain region based on concurrent measurement of the rate of neuronal oxidative energy production (VTCAn) and glutamate neurotransmission cycling (VCycle). 8 Briefly, brain energy budget calculations indicate that cerebral signaling costs approximately 80% of total neuronal energy and that the majority of signaling energy is used on glutamate postsynaptic transmission and action potentials (∼71%) with only 9% spent on glutamate release and cycling.11,12 In fact, most of currently available functional neuroimaging tools [eg, functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET)] are based on the experimental observation that brain energy metabolism is directly related to neuronal signaling. 13 One limitation of fMRI and FDG-PET is that they lack the capacity to concurrently measure the rate of synaptic glutamate release (VCycle). The aim of this PTSD study is to investigate energy-per-cycle (EPC; ie, the VTCAn/VCycle ratio) as a putative biomarker directly related to glutamatergic synaptic strength. 8

Preclinical studies suggest that trauma and chronic stress reduce glutamate synaptic density, downregulate postsynaptic ionotropic glutamate receptors, and alter cortical functional connectivity reflecting an overall reduction in prefrontal synaptic strength. 14 In humans, various brain imaging findings have been considered as biomarkers of this stress-related synaptic dysconnectivity.1,15–17 Trauma and stress-related disorders were repeatedly associated with gray matter deficits, especially in the prefrontal cortex. Reductions in cortical volume and thickness were reported in individual and meta-analysis studies.18–21 Similarly, volumetric and shape analyses correlated trauma and stress psychopathology with gray matter deficit.22–24 At the functional level, task and connectivity studies have identified broad circuit and large-scale brain network disturbances in trauma and stress-related disorders.4,25,26 Moreover, disruption in global brain connectivity in the prefrontal gray matter was repeatedly related to the pathology and treatment of PTSD and other stress-related disorders.27–38 At the neurochemical level, studies have investigated total levels of glutamate or binding potential of glutamate receptors and glutamate-related vesicles.6,34,39–44 These approaches have numerous strengths including wide availability, good space and time resolutions, and ability to conduct whole brain assessments or study the full connectome. A main impediment to the utility of these previously identified biomarkers is the high overlap between healthy control participants and patients. 45 Another limitation is the complexity in interpreting the findings, as these measures do not specifically assess synaptic glutamate transmission but rather upstream input (eg, glutamate receptors or vesicles) or downstream output (eg, functional connectivity). The neuropsychiatry field may greatly benefit from establishing a biomarker that is directly related to synaptic neurotransmission, especially if this biomarker is tightly controlled in normal conditions.

13C Magnetic Resonance spectroscopy (13C MRS), combined with the stable isotope 13C acetate, is a specialized method to measure glutamatergic synaptic strength. 13C MRS allows the computation of EPC, which is the ratio of the rate of neuronal energy production divided by the rate of glutamate/glutamine cycling (VTCAn/Vcycle). This ratio is equivalent to the neuronal energy consumed per glutamate cycle. EPC is a biomarker highly preserved across species and is a unique measure of glutamatergic synaptic strength.46–48 Strength is defined as the synaptic energy consumption (in units of glucose molecules oxidized) required to support the depolarization induced by the release of one neurotransmitter glutamate molecule. These are the major energy consuming processes that contribute to the EPC ratio. Here, we used advanced methods for acquiring 13C MRS in the human frontal lobe,49–52 a brain region closely related to psychopathology that was not previously accessible to 13C MRS studies. 48

In this study, we aimed to demonstrate altered glutamatergic synaptic strength, as measured by EPC, in the prefrontal cortex of patients with PTSD, compared to healthy controls. We hypothesized that the PTSD participants will present a significant reduction in prefrontal EPC.

Methods

Study Participants

Healthy controls and individuals diagnosed with PTSD between the ages of 18 and 65 were enrolled in this study. All study procedures were approved by the Yale University Institutional Review Board. All participants completed an informed consent process prior to enrollment. None of the scans from this cohort were previously reported.

Participants had no contraindication to magnetic resonance imaging, no dementia or significant cognitive or neurodevelopmental disorders, no traumatic brain injury, no unstable medical condition, were neither pregnant nor breastfeeding and were on a medically accepted birth control method. Negative urine toxicology tests and negative pregnancy tests (when applicable) were required. Healthy participants were excluded if they had a lifetime history of any psychiatric disorder. Primary PTSD diagnoses were determined by a structured interview and participants were enrolled if they had: (1) been on a stable dose of serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressants or on no antidepressants for at least 4 weeks; (2) no diagnosis of bipolar or psychotic disorders; (3) no current substance/alcohol use disorder; (4) no current serious suicide risk; and (5) no current treatment with select medications that modulate excitatory aminoacid transporters, eg, riluzole, ceftriaxone, pentoxifylline. Study criteria were ascertained by clinical history, questionnaires, and physical exams. Considering the high comorbidity between PTSD and depression 53 and that our research program focuses on treatments for severe PTSD cases, all PTSD participants met criteria for a secondary diagnosis of major depression. The PTSD Checklist (PCL) and Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS), both self-report measures, were completed to assess PTSD and depression severity, respectively.54,55

13C MRS Acquisition & Processing

Prefrontal 13C MRS acquisition and preprocessing followed our previously established procedures. 8 MRS data were acquired on a 4.0 T whole-body magnet interfaced to a Bruker AVANCE spectrometer (Bruker Instruments, Billerica, MA, USA). Subjects were placed supine in the magnet, with their head immobilized with foam. An RF probe consisting of one circular 13C coil (8.5 cm Ø) and two circular, quadrature driven 1H RF coils (12.5 cm Ø) were used for acquisition of 13C MR spectra from the frontal lobe (Figure S1A-B). Following tuning and acquisition of scout images, second-order shimming of the region of interest (ROI) was performed using phase mapping provided by Bruker.

13C MR spectra were acquired with a pulse-acquire sequence using an adiabatic 90° excitation pulse and optimized repetition time (offset 180 ppm, TR 6s). Nuclear Overhauser enhancement (nOe) was achieved by applying 1H block pulses before the 13C excitation pulse. 1H decoupling during acquisition consists of pseudo noise decoupling as described by Li et al, 50 to decouple the long-range 1H-13C coupling of the carboxylic carbon positions. The pseudo noise decoupling pulse has a constant amplitude and the phase of each 1.2-ms unit pulse is randomly assigned to either 0° or 180°. Following the start of [1 13C]-acetate infusion, 6.5-min blocks of MR spectra were acquired for 120 minutes (Figure S1C and S2).

13C MRS processing was conducted while blinded to the clinical data. Briefly, steady-state spectra were averaged from acquisitions after 70 minutes through the rest of the session. The steady-state spectra were analyzed with −2Hz/6Hz Lorentzian-to-Gaussian conversion and 16-fold zero-filling followed by Fourier transformation. An LC model approach was used to fit the peak areas of the labeled carbon positions of glutamate C5 and glutamine C5 (Figure S1C), which overlapped with aspartate C4. Cramer-Rao Lower Bounds were used to estimate the quality of the individual measurements, averaging 5.8% for glutamate and 9.6% for glutamine/aspartate. The aspartate C4 kinetics closely track that of its glutamate precursor, 56 thus it is considered to have the same percent enrichment as glutamate C5 and was subtracted from the combined glutamine-aspartate peak. The 13C-Glutamate/13C-Glutamine enrichment ratio was computed using peak areas of glutamate C5 and glutamine C5, (ie, glutamate-C5/glutamine-C5 * f), where f is the ratio of glutamate/glutamine, measured by reference 57 ). Then, EPC was calculated based on the relative 13C enrichment of Glutamate over Glutamine at steady state, as follows: VTCAn/Vcycle = [1−(13C-Glutamate/13C-Glutamine)]/(13C-Glutamate/13C-Glutamine), where 13C-Glutamine and 13C-Glutamate represent the steady state 13C enrichments during the infusion of [1 13C]-acetate (ie, ∼ 70-120 min after starting infusion). 58

Statistical Analyses

Before conducting each analysis, the distributions of the outcome measures were examined. Data transformation was not needed. Estimates of variation are provided as standard error of the mean (SEM). Considering that this is a first-in-human study, this should be considered a first-level study implementing a novel technique, rather than a confirmatory study.

Independent t tests and chi-square tests were used to determine differences between groups. Spearman's rank order was used for correlational analyses. Fisher r-to-z transformation was used to compare correlations between groups. General linear model examined the effects of medication status, including age as a covariate. All tests were two-tailed, with the significance threshold set at 0.05. The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (version 24; IBM) software was used for the analyses.

Results

A total of 34 participants (18 healthy & 16 PTSD) successfully completed the study procedures. Sex, race, age, height, and weight were not statistically different between the study groups (Table 1). Though trauma exposure was not exclusionary, only one healthy participant endorsed trauma exposure.

Table 1.

Demographics and Clinical Characteristics.

| PTSD (n = 16) | Healthy (n = 18) | P value a | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 10 (62%) | 11 (61%) | .93 |

| White | 9 (56%) | 11 (61%) | .77 |

| Age (years) | 39.5 ± 3.3 | 34.3 ± 2.9 | .25 |

| Height (inches) | 65.7 ± 1.0 | 65.3 ± 0.8 | .60 |

| Weight (lbs.) | 169 ± 12 | 148 ± 8 | .16 |

| PCL | 45.4 ± 3.9 | 1.8 ± 0.7 | < .01 |

| QIDS | 14.5 ± 0.9 | 1.7 ± 0.4 | < .01 |

Chi-square and independent t tests were used to compare groups.

PTSD: posttraumatic stress disorder; PCL: PTSD Checklist; QIDS: Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology.

We first investigated the effect of group on EPC. We found a 28% reduction of EPC in PTSD (mean ± SEM = 2.2 ± 0.2) compared to healthy controls (mean ± SEM = 3.0 ± 0.2; t = −3.0, df = 32, P = .005; Figure 1). Next, we examined the effect of sex on EPC, which showed no EPC differences between males (mean ± SEM = 2.6 ± 0.2) and females (mean ± SEM = 2.7 ± 0.2; t = −0.3, df = 32, P = .75). However, there was a significant negative correlation between EPC and age (r = −0.46, n = 34, P = .006; Figure 2). Comparing the EPC-age association between study groups showed no statistically significant difference in PTSD (r = −0.41) compared to healthy controls (r = −0.49; z = 0.27, P = .79). Considering the relationship between age and EPC, we conducted a general linear model analysis examining the effect of diagnosis controlling for age. The general linear model showed significant group effects (F(1,31) = 7.3, P = .01), indicating reduced EPC in PTSD compared to healthy control, covarying for age.

Figure 1.

The effects of diagnosis on glutamate neurotransmission strength as measured by energy-per-cycle (EPC). Participants diagnosed with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) were found to have 28% reduction in EPC compared to healthy controls. EPC is a measure of neuronal energetic needs (VTCAn) per glutamate/glutamine cycling (VCycle), which is computed from the relative carbon-13 enrichment of glutamine and glutamate during steady state of [1-13C]-acetate intravenous infusion. The dotted line, at 2.146, marks the lowest EPC value among healthy participants. It shows that the EPC values of only 8 (50%) PTSD individuals overlapped with those of healthy control.

Figure 2.

The association between age and glutamate neurotransmission strength as measured by energy-per-cycle (EPC). There is a significant negative correlation between age and EPC in the full cohort, as well as in the healthy and patient groups considered separately. EPC is a measure of neuronal energetic needs (VTCAn) per glutamate/glutamine cycling (VCycle), which is computed from the relative carbon-13 enrichment of glutamine and glutamate during steady state of [1-13C]-acetate intravenous infusion. Abbreviations: PTSD: posttraumatic stress disorder.

Discussion

The study established the feasibility and methods for determining EPC in the prefrontal cortex in vivo in humans using [1 13C]-acetate MRS, a relatively less complex and less burdensome approach than using 13C-glucose. The results also provided the first in vivo evidence of reduced prefrontal EPC in trauma-exposed individuals with PTSD, suggestive of a reduction in glutamatergic synaptic strength in this patient population. The data provided supportive evidence about the utility of EPC as measured by [1 13C]-acetate MRS. In particular, the values of EPC in healthy participants overlapped with only 8 (ie, 50%) PTSD individuals, indicating that EPC is a tightly controlled biomarker in normal conditions. Together, these data underscore the role of the EPC biomarker in the neurobiology and treatment of trauma and stress-related psychopathology.

The use of EPC as measured by 13C-acetate MRS could hold great promise as a powerful translational treatment target biomarker. (1) The relationship between neuronal energetics (VTCAn) and glutamate cycling (Vcycle) is comparable among rodents and humans. 47 This could be highly useful during early stages of drug development, as pharmacoimaging paradigms established in rodents could be readily translated to humans. (2) EPC is stable across differing levels of neuronal activation and brain state, maintaining on average an approximately constant ratio in anesthetized, asleep, and awake brains.10,47 This overall stability across brain activity states is a major strength as biomarker, which simplifies acquisition paradigms and could reduce potential state dependent confounding effects across studies. (3) The EPC ratio was previously related to psychopathology. 48 (4) Another advantage is that in 13C-acetate MRS, EPC measure is calculated based on the relative 13C enrichment of Glutamate over Glutamine during isotopic steady state as opposed to a lengthy dynamic time course in the magnet. Together, these characteristics will ensure the rigor and reproducibility of the biomarker, as studies targeting EPC would (a) only need to acquire scans during steady state infusion of acetate, without the need for 2 h acquisition to capture the full time-course of acetate kinetics. (b) The measure would not necessarily require sophisticated kinetic modeling or various input functions (eg, plasma enrichment). (c) As a ratio of 2 metabolites acquired concurrently, it also does provide an optimal internal reference that obviates the need for common MRS correction methods (eg, phantom replacement, tissue composition, etc). (d) Given its dependence on steady state only, it may also permit the exploration of various routes of acetate administration instead of the intravenous infusion route. (e) Signal to noise is also optimal considering the high level of 13C enrichment during steady state and the fact that it is an average of long acquisition (∼ 1 h in the current study). Together, these strengths of the EPC measure could significantly reduce the complexity of 13C MRS acquisition and facilitate its deployment at large scale if this biomarker was confirmed to be of clinical utility.

Overall, the findings of the current study highly support the use of EPC as a complimentary biomarker to assess the role of glutamatergic synaptic strength in the pathophysiology of trauma and stress-related disorders. As a ratio of VTCA/VCycle, EPC measured by 13C-acetate MRS does not differentiate between reduction in VTCA or increase in VCycle, and vice versa. However, this limitation is also a major strength of the biomarker as it is also a ratio of glutamate/glutamine 13C enrichment at steady state, providing ideal internal reference as well as optimal signal to noise. In our previous studies, we used 13C-glucose MRS to measure VTCA and VCycle independently.8,48 Yet, we found the EPC ratio (ie, VTCA/VCycle) to be the most salient biomarker. In one 13C-glucose MRS study, we found a 26% reduction in occipital EPC in depressed patients compared to healthy controls. 48 In a separate study, we found that the rapid acting antidepressant ketamine significantly altered prefrontal EPC in healthy and depressed participants, as indicated by its differential effects on glutamate and glutamine enrichment. 8 These latter findings were consistent with preclinical data showing differential effects of ketamine on prefrontal glutamate and glutamine enrichment.59,60 Finally, our previous data correlated prefrontal EPC with the psychotomimetic effects of ketamine, suggesting that EPC is not only relevant to antidepressants and stress-related psychopathology but also perhaps to psychosis mechanisms. 8

Another limitation of EPC is the lack of spatial resolution with the current 13C MRS methods, which are limited to large single cortical ROI and do not permit localization to a specific brain region, eg, anterior cingulate. However, the cortical ROI targeted in this study (Figure S1) is believed to play a critical role in PTSD psychopathology. In addition, based on postmortem and preclinical data, the glutamate abnormalities appear to be widespread throughout the prefrontal cortex.14,61 Our colleagues are currently developing novel 1H-13C MRS approaches that will provide higher resolution as well as access to deeper brain structures, which could be used in future studies. 62 Finally, while we demonstrated the utility of EPC in patients with PTSD, future larger studies are still required to determine the effects of antidepressants and the specificity of EPC alterations to PTSD, trauma exposure or the comorbid depression.

Conclusion

The current report provides the logical intuition for computing glutamate synaptic strength in vivo in humans and details the methods for acquiring 13C-acetate MRS in the prefrontal cortex and for estimating EPC. It briefly describes the EPC alterations in PTSD and discusses the strengths and limitation of EPC as measured by 13C-acetate MRS. Overall, the results of this study support the glutamate synaptic dysconnectivity models of trauma and stress-related psychopathology.1,6 We showed 28% reduction in prefrontal EPC in PTSD, with a limited overlap between patients and healthy individuals (Figure 1). These findings are comparable to previous findings in occipital EPC measured by 13C-glucose MRS, 48 suggesting widespread cortical disruption in EPC with tightly controlled EPC values in normal condition. Another interesting finding is the negative correlation between age and EPC, raising the possibility that the observed reduction in cortical EPC might be consistent with a phenomenon of accelerated aging in trauma and stress-related disorders. 63 Future studies should investigate the effect of antidepressants on EPC and examine whether the prefrontal EPC disruption is related to trauma exposure, to the PTSD severity and comorbidities, or to both.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-css-10.1177_24705470221092734 for Prefrontal Glutamate Neurotransmission in PTSD: A Novel Approach to Estimate Synaptic Strength in Vivo in Humans by Lynnette A. Averill, Lihong Jiang, Prerana Purohit, Anastasia Coppoli, Christopher L. Averill, Jeremy Roscoe, Benjamin Kelmendi, Henk M. De Feyter, Robin A de Graaf, Ralitza Gueorguieva, Gerard Sanacora, John H. Krystal, Douglas L. Rothman, Graeme F. Mason and Chadi G. Abdallah in Chronic Stress

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the individuals who participated in these studies for their invaluable contribution.

Footnotes

Authors Contributions: Conceptualization, C.G.A., G.S., J.H.K., D.L.R. and G.F.M.; Methodology, C.G.A., H.M.DF., R.A.dG., D.L.R. and G.F.M.; Data Curation: C.G.A., L.A.A., L.J., P.P., A.C., C.L.A., J.R., B.K., and G.F.M.; Formal Analysis, C.G.A. and R.G.; Investigation, C.G.A., L.A.A., L.J., P.P., A.C., C.L.A., J.R., B.K., R.G., G.S., J.H.K., D.L.R. and G.F.M.; Writing – Original Draft, C.G.A.; Writing – Review/Edit, all authors; Funding Acquisition, C.G.A., J.H.K. and G.F.M.; Resources, C.G.A., L.A.A. and G.F.M.; Supervision, C.G.A. and G.F.M.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Dr. Averill has served as a consultant, speaker and/or on advisory boards for Guidepoint, Transcend Therapeutics, and Ampelis. Dr. Abdallah has served as a consultant, speaker and/or on advisory boards for Aptinyx, Genentech, Janssen, Psilocybin Labs, Lundbeck, Guidepoint, and FSV7, and as editor of Chronic Stress for Sage Publications, Inc. He also filed a patent for using mTORC1 inhibitors to augment the effects of antidepressants (Aug 20, 2018). Dr. Krystal is a consultant for Aptinyx, Inc., Atai Life Sciences, AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals, Biogen, Idec, MA, Biomedisyn Corporation, Bionomics, Limited (Australia), Boehringer Ingelheim International, Cadent Therapeutics, Inc., Clexio Bioscience, Ltd., COMPASS Pathways, Limited, United Kingdom, Concert Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Epiodyne, Inc., EpiVario, Inc., Greenwich Biosciences, Inc., Heptares Therapeutics, Limited (UK), Janssen Research & Development, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Otsuka America Pharmaceutical, Inc., Perception Neuroscience Holdings, Inc., Spring Care, Inc., Sunovion Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Takeda Industries, Taisho Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. Dr. Krystal also reports the following disclosures: Scientific Advisory Board: Biohaven Pharmaceuticals, BioXcel Therapeutics, Inc. (Clinical Advisory Board), Cadent Therapeutics, Inc. (Clinical Advisory Board), Cerevel Therapeutics, LLC, EpiVario, Inc., Eisai, Inc., Lohocla Research Corporation, Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, PsychoGenics, Inc., RBNC Therapeutics, Inc., Tempero Bio, Inc., Terran Biosciences, Inc. Stock: Biohaven Pharmaceuticals, Sage Pharmaceuticals, Spring Care, Inc. Stock Options: Biohaven Pharmaceuticals Medical Sciences, EpiVario, Inc., RBNC Therapeutics, Inc., Terran Biosciences, Inc. Tempero Bio, Inc. Income Greater than $10,000: Editorial Board: Editor - Biological Psychiatry. Patents and Inventions: (1) Seibyl JP, Krystal JH, Charney DS. Dopamine and noradrenergic reuptake inhibitors in treatment of schizophrenia. US Patent #:5,447,948.September 5, 1995. (2) Vladimir, Coric, Krystal, John H, Sanacora, Gerard – Glutamate Modulating Agents in the Treatment of Mental Disorders. US Patent No. 8,778,979 B2 Patent Issue Date: July 15, 2014. US Patent Application No. 15/695,164: Filing Date: 09/05/2017. (3) Charney D, Krystal JH, Manji H, Matthew S, Zarate C., - Intranasal Administration of Ketamine to Treat Depression United States Patent Number: 9592207, Issue date: 3/14/2017. &#9;Licensed to Janssen Research & Development. (4) Zarate, C, Charney, DS, Manji, HK, Mathew, Sanjay J, Krystal, JH, Yale University “Methods for Treating Suicidal Ideation”, Patent Application No. 15/379,013 filed on December 14, 2016 by Yale University Office of Cooperative Research. (5) Arias A, Petrakis I, Krystal JH. – Composition and methods to treat addiction. Provisional Use Patent Application no.61/973/961. April 2, 2014. Filed by Yale University Office of Cooperative Research. (6) Chekroud, A., Gueorguieva, R., & Krystal, JH. “Treatment Selection for Major Depressive Disorder” [filing date 3rd June 2016, USPTO docket number Y0087.70116US00]. Provisional patent submission by Yale University. (7) Gihyun, Yoon, Petrakis I, Krystal JH – Compounds, Compositions and Methods for Treating or Preventing Depression and Other Diseases. U. S. Provisional Patent Application No. 62/444,552, filed on January10, 2017 by Yale University Office of Cooperative Research OCR 7088 US01. (8) Abdallah, C, Krystal, JH, Duman, R, Sanacora, G. Combination Therapy for Treating or Preventing Depression or Other Mood Diseases. U.S. Provisional Patent Application No. 62/719,935 filed on August 20, 2018 by Yale University Office of Cooperative Research OCR 7451 US01. On Non-Federal Research Support: AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals provides the drug, Saracatinib, for research related to NIAAA grant “Center for Translational Neuroscience of Alcoholism [CTNA-4] Novartis provides the drug, Mavoglurant, for research related to NIAAA grant “Center for Translational Neuroscience of Alcoholism [CTNA-4] Dr. Gueorguieva discloses royalties from book “Statistical Methods in Psychiatry and Related Fields” published by CRC Press, honorarium as a member of the Working Group for PTSD Adaptive Platform Trial of Cohen Veterans Bioscience and a United States patent application 20200143922 by Yale University: Chekroud, A., Krystal, J., Gueorguieva, R. and Chandra, A. “Methods and Apparatus for Predicting Depression Treatment Outcomes”. Dr. Sanacora has received consulting fees from Alkermes, Allergan, AstraZeneca, Avanier Pharmaceuticals, Axsome Therapeutics, Biohaven Pharmaceuticals, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Clexio Biosciences, Denovo Biopharma, EMA Wellness, Engrail, Gilgamesh, Hoffmann–La Roche, Intra-Cellular Therapies, Janssen, Lundbeck, Merck, Minerva Neurosciences, Navitor Pharmaceuticals, Neurocrine, Novartis, Noven Pharmaceuticals, Otsuka, Perception Neuroscience, Praxis Therapeutics, Sage Pharmaceuticals, Seelos Pharmaceuticals, Taisho Pharmaceuticals, Teva, Valeant, Vistagen Therapeutics, and XW labs. Scientific Advisory Board: Biohaven Pharmaceuticals, Gilgamesh Pharmaceuticals. VistaGen Therapetutics Stock: Biohaven Pharmaceuticals, Gilead Sciences. Stock Options: Biohaven Pharmaceuticals Medical Sciences, Income Greater than : Biohaven pharmaceteuticals. Patents and Inventions: (1) Vladimir, Coric, Krystal, John H, Sanacora, Gerard – Glutamate Modulating Agents in the Treatment of Mental Disorders. US Patent No. 8,778,979 B2 Patent Issue Date: July 15, 2014. US Patent Application No. 15/695,164: Filing Date: 09/05/2017. (2) Abdallah, C, Krystal, JH, Duman, R, Sanacora, G. Combination Therapy for Treating or Preventing Depression or Other Mood Diseases. U.S. Provisional Patent Application No. 62/719,935 filed on August 20, 2018 by Yale University Office of Cooperative Research OCR 7451 US01. On Non-Federal Research Support: Dr. Sanacora has received research contracts from AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Johnson & Johnson, Hoffmann–La Roche, Merck, Naurex, Servier Pharmaceuticals, and Usona. No-cost medication was provided to Dr. Sanacora for an NIH-sponsored study by Sanofi-Aventis. All other authors declared no conflict of interests.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Funding and research support were provided by NIMH (R01MH112668), NIAAA (R01AA021984), the VA National Center for PTSD, Brain & Behavior Foundation (NARSAD), Clinical Neuroscience Research Unit (CNRU) at Connecticut Mental Health Center, Yale Center for Clinical Investigation (YCCI UL1 RR024139), an NIH Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) and the Beth K and Stuart Yudofsky Chair in the Neuropsychiatry of Military Post Traumatic Stress Syndrome. LAA receives salary support from the VA Clinical Sciences Research & Development (IK2-CX0001873) and the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (YIG-0-004-16). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the sponsors, the Department of Veterans Affairs, NIH, or the U.S. Government.

Ethical Approval: The study protocol was approved by an institutional review board.

Informed Consent: All participants provided informed consent.

ORCID iD: Chadi G. Abdallah https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5783-6181

Christopher L. Averill https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7575-6142

Lynnette A. Averill https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8985-9975

Trial Registration: Not applicable, because this article does not contain any clinical trials.

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Abdallah CG, Averill LA, Akiki TJ, et al. The neurobiology and pharmacotherapy of posttraumatic stress disorder. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2019; 59(1): 171–189. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010818-021701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pitman RK, Rasmusson AM, Koenen KC, et al. Biological studies of post-traumatic stress disorder. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012; 13(11): 769–787. doi: 10.1038/nrn3339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abdallah CG, Southwick SM, Krystal JH. Neurobiology of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD): a path from novel pathophysiology to innovative therapeutics. Neurosci Lett. 2017; 649: 130–132. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2017.04.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Akiki TJ, Averill CL, Abdallah CG. A network-based neurobiological model of PTSD: evidence from structural and functional neuroimaging studies. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2017; 19(11): 81. doi: 10.1007/s11920-017-0840-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sheynin J, Liberzon I. Circuit dysregulation and circuit-based treatments in posttraumatic stress disorder. Neurosci Lett. 2017; 649: 133–138. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2016.11.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Averill LA, Purohit P, Averill CL, Boesl MA, Krystal JH, Abdallah CG. Glutamate dysregulation and glutamatergic therapeutics for PTSD: evidence from human studies. Neurosci Lett. 2017; 649: 147–155. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2016.11.064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davis MT, Holmes SE, Pietrzak RH, Esterlis I. Neurobiology of chronic stress-related psychiatric disorders: evidence from molecular imaging studies. Chronic Stress. 2017; 1: 2470547017710916. doi: 10.1177/2470547017710916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abdallah CG, De Feyter HM, Averill LA, et al. The effects of ketamine on prefrontal glutamate neurotransmission in healthy and depressed subjects. Neuropsychopharmacology 2018; 43(10): 2154–2160. doi: 10.1038/s41386-018-0136-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malenka RC, Bear MF. LTP And LTD: an embarrassment of riches. Neuron. 2004; 44(1): 5–21. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shulman RG, Rothman DL, Behar KL, Hyder F. Energetic basis of brain activity: implications for neuroimaging. Trends Neurosci. 2004; 27(8): 489–495. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2004.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yu Y, Herman P, Rothman DL, Agarwal D, Hyder F. Evaluating the gray and white matter energy budgets of human brain function. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2018; 38(8): 1339–1353. doi: 10.1177/0271678X17708691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Howarth C, Gleeson P, Attwell D. Updated energy budgets for neural computation in the neocortex and cerebellum. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2012; 32(7): 1222–1232. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2012.35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Herman P, Sanganahalli BG, Blumenfeld H, Rothman DL, Hyder F. Quantitative basis for neuroimaging of cortical laminae with calibrated functional MRI. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013; 110(37): 15115–15120. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1307154110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Popoli M, Yan Z, McEwen BS, Sanacora G. The stressed synapse: the impact of stress and glucocorticoids on glutamate transmission. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012; 13(1): 22–37. doi: 10.1038/nrn3138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kadriu B, Greenwald M, Henter ID, et al. Ketamine and serotonergic psychedelics: common mechanisms underlying the effects of rapid-acting antidepressants. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2021; 24(1): 8–21. doi: 10.1093/ijnp/pyaa087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kraus C, Wasserman D, Henter ID, Acevedo-Diaz E, Kadriu B, Zarate CA, Jr. The influence of ketamine on drug discovery in depression. Drug Discov Today. 2019; 24(10): 2033–2043. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2019.07.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krystal JH, Abdallah CG, Averill LA, et al. Synaptic loss and the pathophysiology of PTSD: implications for ketamine as a prototype novel therapeutic. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2017; 19(10): 74. doi: 10.1007/s11920-017-0829-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Averill LA, Abdallah CG, Pietrzak RH, et al. Combat exposure severity is associated with reduced cortical thickness in combat veterans: a preliminary report. Chronic Stress. 2017; 1: 2470547017724714. doi: 10.1177/2470547017724714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schmaal L, Hibar DP, Samann PG, et al. Cortical abnormalities in adults and adolescents with major depression based on brain scans from 20 cohorts worldwide in the ENIGMA Major Depressive Disorder Working Group. Mol Psychiatry. 2017; 22(6): 900–909. doi: 10.1038/mp.2016.60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang X, Xie H, Chen T, et al. Cortical volume abnormalities in posttraumatic stress disorder: an ENIGMA-psychiatric genomics consortium PTSD workgroup mega-analysis. Mol Psychiatry. 2021; 26(8): 4331–4343 doi: 10.1038/s41380-020-00967-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wrocklage KM, Averill LA, Cobb Scott J, et al. Cortical thickness reduction in combat exposed U.S. veterans with and without PTSD. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2017; 27(5): 515–525. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2017.02.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Akiki TJ, Averill CL, Wrocklage KM, et al. The association of PTSD symptom severity with localized hippocampus and amygdala abnormalities. Chronic Stress. 2017; 1: 2470547017724069. doi: 10.1177/2470547017724069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gosnell S, Meyer M, Jennings C, et al. Hippocampal volume in psychiatric diagnoses: should psychiatry biomarker research account for comorbidities? Chronic Stress. 2020; 4: 2470547020906799. doi: 10.1177/2470547020906799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Logue MW, van Rooij SJH, Dennis EL, et al. Smaller hippocampal volume in posttraumatic stress disorder: a multisite ENIGMA-PGC study: subcortical volumetry results from posttraumatic stress disorder consortia. Biol Psychiatry. 2018; 83(3): 244–253. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2017.09.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Negreira AM, Abdallah CG. A review of fMRI affective processing paradigms used in the neurobiological study of posttraumatic stress disorder. Chronic Stress. 2019; 3: 2470547019829035. doi: 10.1177/2470547019829035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seidemann R, Duek O, Jia R, Levy I, Harpaz-Rotem I. The reward system and post-traumatic stress disorder: does trauma affect the way we interact with positive stimuli? Chronic Stress. 2021; 5: 2470547021996006. doi: 10.1177/2470547021996006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abdallah CG, Averill CL, Ramage AE, et al. Reduced salience and enhanced central executive connectivity following PTSD treatment. Chronic Stress. 2019; 3: 2470547019838971. doi: 10.1177/2470547019838971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abdallah CG, Averill CL, Ramage AE, et al. Salience network disruption in U.S. Army soldiers with posttraumatic stress disorder. Chronic Stress. 2019; 3: 2470547019850467. doi: 10.1177/2470547019850467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abdallah CG, Averill CL, Salas R, et al. Prefrontal connectivity and glutamate transmission: relevance to depression pathophysiology and ketamine treatment. Biol Psychiatry Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging. 2017; 2(7): 566–574. doi: 10.1016/j.bpsc.2017.04.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abdallah CG, Averill LA, Collins KA, et al. Ketamine treatment and global brain connectivity in Major depression. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2017; 42(6): 1210–1219. doi: 10.1038/npp.2016.186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abdallah CG, Dutta A, Averill CL, et al. Ketamine, but not the NMDAR antagonist lanicemine, increases prefrontal global connectivity in depressed patients. Chronic Stress. 2018; 2: 2470547018796102. doi: 10.1177/2470547018796102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abdallah CG, Wrocklage KM, Averill CL, et al. Anterior hippocampal dysconnectivity in posttraumatic stress disorder: a dimensional and multimodal approach. Transl Psychiatry. 2017; 7(2): e1045. doi: 10.1038/tp.2017.12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Holmes SE, Scheinost D, DellaGioia N, et al. Cerebellar and prefrontal cortical alterations in PTSD: structural and functional evidence. Chronic Stress. 2018; 2: 2470547018786390. doi: 10.1177/2470547018786390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Holmes SE, Scheinost D, Finnema SJ, et al. Lower synaptic density is associated with depression severity and network alterations. Nat Commun. 2019; 10(1): 1529. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09562-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Murrough JW, Abdallah CG, Anticevic A, et al. Reduced global functional connectivity of the medial prefrontal cortex in major depressive disorder. Hum Brain Mapp. 2016; 37(9): 3214–3223. doi: 10.1002/hbm.23235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nemati S, Abdallah CG. Increased cortical thickness in patients with major depressive disorder following antidepressant treatment. Chronic Stress. 2020; 4: 2470547019899962. doi: 10.1177/2470547019899962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Scheinost D, Holmes SE, DellaGioia N, et al. Multimodal investigation of network level effects using intrinsic functional connectivity, anatomical covariance, and structure-to-function correlations in unmedicated major depressive disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2018; 43(5): 1119–1127. doi: 10.1038/npp.2017.229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang L, Dai Z, Peng H, et al. Overlapping and segregated resting-state functional connectivity in patients with major depressive disorder with and without childhood neglect. Hum Brain Mapp. 2014; 35(4): 1154–1166. doi: 10.1002/hbm.22241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Abdallah CG, Hannestad J, Mason GF, et al. Metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 and glutamate involvement in major depressive disorder: a multimodal imaging study. Biol Psychiatry Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging. 2017; 2(5): 449–456. doi: 10.1016/j.bpsc.2017.03.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Holmes SE, Girgenti MJ, Davis MT, et al. Altered metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 markers in PTSD: in vivo and postmortem evidence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017; 114(31): 8390–8395. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1701749114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Meyerhoff DJ, Mon A, Metzler T, Neylan TC. Cortical gamma-aminobutyric acid and glutamate in posttraumatic stress disorder and their relationships to self-reported sleep quality. Sleep. 2014; 37(5): 893–900. doi: 10.5665/sleep.3654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pennington DL, Abe C, Batki SL, Meyerhoff DJ. A preliminary examination of cortical neurotransmitter levels associated with heavy drinking in posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2014; 224(3): 281–287. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2014.09.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rosso IM, Crowley DJ, Silveri MM, Rauch SL, Jensen JE. Hippocampus glutamate and N-acetyl aspartate markers of excitotoxic neuronal compromise in posttraumatic stress disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2017; 42(8): 1698–1705. doi: 10.1038/npp.2017.32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang ZY, Quan H, Peng ZL, Zhong Y, Tan ZJ, Gong QY. Proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy revealed differences in the glutamate + glutamine/creatine ratio of the anterior cingulate cortex between healthy and pediatric post-traumatic stress disorder patients diagnosed after 2008 Wenchuan earthquake. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2015; 69(12): 782–790. doi: 10.1111/pcn.12332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Paulus MP, Thompson WK. The challenges and opportunities of small effects: the new normal in academic psychiatry. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019; 76(4): 353–354. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.4540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rothman DL, De Feyter HM, de Graaf RA, Mason GF, Behar KL. 13C MRS studies of neuroenergetics and neurotransmitter cycling in humans. NMR Biomed. 2011; 24(8): 943–957. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hyder F, Rothman DL, Bennett MR. Cortical energy demands of signaling and nonsignaling components in brain are conserved across mammalian species and activity levels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013; 110(9): 3549–3554. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1214912110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Abdallah CG, Jiang L, De Feyter HM, et al. Glutamate metabolism in major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2014; 171(12): 1320–1327. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.14010067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li S, Zhang Y, Wang S, et al. 13C MRS of occipital and frontal lobes at 3 T using a volume coil for stochastic proton decoupling. NMR Biomed. 2010; 23(8): 977–985. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li S, Zhang Y, Wang S, et al. In vivo 13C magnetic resonance spectroscopy of human brain on a clinical 3 T scanner using [2-13C]glucose infusion and low-power stochastic decoupling. Magn Reson Med. 2009; 62(3): 565–573. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sailasuta N, Robertson LW, Harris KC, Gropman AL, Allen PS, Ross BD. Clinical NOE 13C MRS for neuropsychiatric disorders of the frontal lobe. J Magn Reson. 2008; 195(2): 219–225. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2008.09.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Boumezbeur F, Mason GF, de Graaf RA, et al. Altered brain mitochondrial metabolism in healthy aging as assessed by in vivo magnetic resonance spectroscopy. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2010; 30(1): 211–221. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2009.197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bleich A, Koslowsky M, Dolev A, Lerer B. Post-traumatic stress disorder and depression. An analysis of comorbidity. Br J Psychiatry. 1997; 170(5): 479–482. doi: 10.1192/bjp.170.5.479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Moshier SJ, Lee DJ, Bovin MJ, et al. An empirical crosswalk for the PTSD checklist: translating DSM-IV to DSM-5 using a veteran sample. J Trauma Stress. 2019; 32(5): 799–805. doi: 10.1002/jts.22438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Ibrahim HM, et al. The 16-item quick inventory of depressive symptomatology (QIDS), clinician rating (QIDS-C), and self-report (QIDS-SR): a psychometric evaluation in patients with chronic major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2003; 54(5): 573–583. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(02)01866-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gruetter R, Seaquist ER, Ugurbil K. A mathematical model of compartmentalized neurotransmitter metabolism in the human brain. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2001; 281(1): E100–E112. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2001.281.1.E100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lally N, An L, Banerjee D, et al. Reliability of 7T (1) H-MRS measured human prefrontal cortex glutamate, glutamine, and glutathione signals using an adapted echo time optimized PRESS sequence: a between- and within-sessions investigation. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2016; 43(1): 88–98. doi: 10.1002/jmri.24970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lebon V, Petersen KF, Cline GW, et al. Astroglial contribution to brain energy metabolism in humans revealed by 13C nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy: elucidation of the dominant pathway for neurotransmitter glutamate repletion and measurement of astrocytic oxidative metabolism. J Neurosci. 2002; 22(5): 1523–1531. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-05-01523.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chowdhury GM, Behar KL, Cho W, Thomas MA, Rothman DL, Sanacora G. 1H-[13C]-nuclear Magnetic resonance spectroscopy measures of ketamine’s effect on amino acid neurotransmitter metabolism. Biol Psychiatry. 2012; 71(11): 1022–1025. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.11.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chowdhury GM, Zhang J, Thomas M, et al. Transiently increased glutamate cycling in rat PFC is associated with rapid onset of antidepressant-like effects. Mol Psychiatry. 2017; 22(1): 120–126. doi: 10.1038/mp.2016.34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sanacora G, Treccani G, Popoli M. Towards a glutamate hypothesis of depression: an emerging frontier of neuropsychopharmacology for mood disorders. Neuropharmacology. 2012; 62(1): 63–77. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.07.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rothman DL, de Graaf RA, Hyder F, Mason GF, Behar KL, De Feyter HM. In vivo (13) C and (1) H-[(13) C] MRS studies of neuroenergetics and neurotransmitter cycling, applications to neurological and psychiatric disease and brain cancer. NMR Biomed. 2019; 32(10): e4172. doi: 10.1002/nbm.4172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bersani FS, Mellon SH, Reus VI, Wolkowitz OM. Accelerated aging in serious mental disorders. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2019; 32(5): 381–387. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-css-10.1177_24705470221092734 for Prefrontal Glutamate Neurotransmission in PTSD: A Novel Approach to Estimate Synaptic Strength in Vivo in Humans by Lynnette A. Averill, Lihong Jiang, Prerana Purohit, Anastasia Coppoli, Christopher L. Averill, Jeremy Roscoe, Benjamin Kelmendi, Henk M. De Feyter, Robin A de Graaf, Ralitza Gueorguieva, Gerard Sanacora, John H. Krystal, Douglas L. Rothman, Graeme F. Mason and Chadi G. Abdallah in Chronic Stress