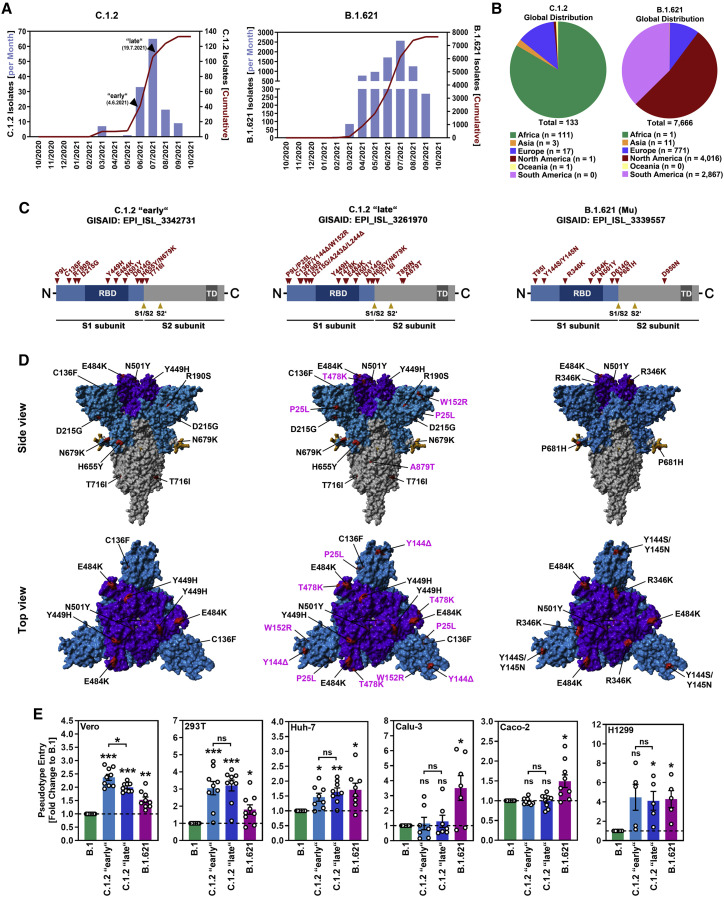

Figure 1.

Spike proteins of SARS-CoV-2 variants C.1.2 and B.1.621 harbor several mutations and enable enhanced entry into certain cell lines

(A) Epidemiology of SARS-CoV-2 variants C.1.2 and B.1.621 (as of September 10, 2021; based on data deposited in the GISAID database). Arrowheads indicate the time points when isolates C.1.2 “early” and C.1.2 “late” were detected.

(B) Global distribution of SARS-CoV-2 variants C.1.2 and B.1.621 (as of September 10, 2021; based on data deposited in the GISAID database).

(C) Schematic overview and S protein domain organization. Mutations compared with SARS-CoV-2 Wuhan-Hu-1 are highlighted in red. Abbreviations: RBD, receptor-binding domain; TD, transmembrane domain.

(D) Location of C.1.2 “early,” C.1.2 “late,” and B.1.621-specific mutations in the context of the trimeric spike protein. Color code: light blue, S1 subunit with RBD in dark blue; gray, S2 subunit; orange, S1/S2 and S2′ cleavage sites; red, mutated amino acid residues (compared with SARS-CoV-2 Wuhan-Hu-1; pink labels highlight differences between the two C.1.2 S proteins).

(E) Pseudotyped particles harboring the indicated S proteins were inoculated onto the indicated cell lines. Transduction efficiency was quantified at 16–18 h post inoculation and normalized against B.1 S (set as 1). Shown are the average (mean) data from five to nine biological replicates (each performed with technical quadruplicates). Error bars indicate the standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical significance was analyzed by two-tailed Student’s t test with Welch correction (p > 0.05, not significant [ns]; p ≤ 0.05, ∗; p ≤ 0.01, ∗∗; p ≤ 0.001, ∗∗∗).

See also Figure S1.