Abstract

Background:

Depression is a leading cause of disease burden worldwide but is often undertreated in low- and middle-income countries. Reasons behind the treatment gap vary, but many highlight a lack of interventions which speak to the socio-economic and structural realties that are associated to mental health problems in many settings, including South Africa. The COURRAGE-PLUS intervention responds to this gap, by combining a collective narrative therapy (9 weeks) intervention, with a social intervention promoting group-led practical action against structural determinants of poor mental health (4 weeks), for a total of 13 sessions. The overall aim is to promote mental health, while empowering communities to acknowledge, and respond in locally meaningful ways to social adversity linked to development of mental distress.

Aim:

To pilot and evaluate the effectiveness of a complex intervention – COURRAGE-PLUS on symptoms of depression as assessed by the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) among a sample of women facing contexts of adversity in Gauteng, South Africa.

Methods:

PHQ-9 scores were assessed at baseline, post collective narrative therapy (midline), and post social intervention (endline). Median scores and corresponding interquartile ranges were computed for all time points. Differences in scores between time points were tested with a non-parametric Friedman test. The impact across symptom severities was compared descriptively to identify potential differences in impact across categories of symptom severity within our sample.

Results:

Participants’ (n = 47) median depression score at baseline was 11 (IQR = 7) and reduced to 4 at midline (IQR = 7) to 0 at endline (IQR = 2.5). The Friedman test showed a statistically significant difference between depression scores across time points, (2) = 49.29, p < .001. Median depression scores were reduced to 0 or 1 Post-Intervention across all four severity groups.

Conclusions:

COURRAGE-PLUS was highly effective at reducing symptoms of depression across the spectrum of severities in this sample of women facing adversity, in Gauteng, South Africa. Findings supports the need for larger trials to investigate collective narrative storytelling and social interventions as community-based interventions for populations experiencing adversity and mental distress.

Keywords: Depression, South Africa, narrative therapy, social interventions, adversity

Introduction

Depression is a leading contributor to global disease burden (World Health Organisation, 2020) with recent evidence suggesting that African countries have experienced between 50% and 200% increases in incidence rates between 1997 and 2017 (Liu et al., 2020). Populations exposed to socioeconomic hardship, and multiple forms of violence are particularly vulnerable to depression (Lund et al., 2018), with women experiencing rates up to 2× as high as men globally (Albert, 2015). In addition to poverty, gendered differences in prevalence rates are often linked to experiences of gender-based violence (Rees et al., 2011) precarious employment (Rönnblad et al., 2019) and care roles (Burgess & Campbell, 2014), which carry their own risks for poor mental health (Ridley et al., 2020). These burdens intersect with appropriateness (Burgess, 2015), and availability of treatment and human resources, particularly in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) (Patel et al., 2011). In attempt to redress the imbalance between the need for and availability of mental health care, a recent World Health Organisation (WHO, 2017) position paper called for scalable mental health interventions that are tailored to people living through adversity; including economic hardship, environmental and political crises, and various forms of violence and victimisation (World Health Organisation, 2017). Suggestions argued for the scale up of group based problem-solving and cognitive therapies.

However, developments in this area are driven by the adaptation of interventions and models often developed within high-income and western paradigms of health and illness to other parts of the world, leaving many to question their appropriateness (Cooper, 2016; Gearing et al., 2012, Kienzler, 2020). In response to the disconnect between traditional cultural understandings and contemporary mental health practices (Kaiser & Jo Weaver, 2019) there have been some attempts to address cross-cultural relevance of approaches, evidenced by the expansion of culture-based diagnostic frameworks within the DSM-V (Jacob, 2014). Beyond this, interventions still struggle to meaningfully engage with structural and social determinants of mental health, particularly on-going experiences of violence, racial and other forms of discrimination, and poverty (Mills, 2015; Mills & Fernando, 2014; Summerfield, 2013). Social interventions, defined loosely as any intervention with the ability to deliver social benefits to their beneficiaries. Common examples include social welfare, safety nets such as cash-transfers and grants, and are growing in their appeal within mental health spaces (Johnson, 2017). However, within therapeutic spaces, the current emphasis has been on promoting socio-relational strategies, such as opportunities to build relationships and social capital (Flores et al., 2018). In response to these challenges, Burgess et al. (2020) call for treatment spaces to expand their development and deployment of social interventions that focus on increasing the abilities of communities affected by social adversity, to identify, strengthen existing abilities and organise resources to tackle structural sources of mental health problems, collectively where possible.

Our study responds to these gaps, through the pilot of an intervention combining psychological therapy based on Southern African indigenous principles of wellbeing, with a package of sessions to develop skills and confidence that may contribute to challenging long-standing adversities that drive poor mental health in everyday contexts, namely poverty.

The intervention

COURRAGE-PLUS is a 13-week group counselling intervention that combines collective narrative counselling with support and training in developing collective responses to economic and social hardships (see Table 1). It combines the COURRAGE intervention, with support to tackle social determinants of mental health. COURRAGE was developed in 2014 by the senior author, a Narrative Therapist and director of PHOLA, a South African organisation addressing the effects of trauma, violence and abuse through psychosocial approaches. Over nine weekly group sessions, COURRAGE aims to improve the mental health of women experiencing violence, abuse and complex trauma through combining collective narrative therapy with indigenous principles and practices anchored to values, ritual and ceremony, mainstays within narrative practice (White, 2003). Narrative therapy and related principles utilise a neutral and respectful approach to community work and counselling, facilitating a process which supports people emerging as experts of their own life. Narrative practice disconnects the problem from the individual, and instead focuses on meaning-making, often through stories and collective sharing (Zhou et al., 2020). Within the COURRAGE model, narrative principles aim to link people’s existing skills, knowledge, values and dreams to culture, relationships and wider social history, using storytelling and creative approaches. The pillar of the model is its application of Ubuntu principles, which reinforces the importance of the collective and community approaches to wellbeing and overcoming adversity. When combined, The COURRAGE approach helps participants imagine the self in different ways, moving beyond ideas of victimhood and perseveration on suffering, to also highlight instances where women may have agency and control in their life history, revising traumatic experiences through a social justice lens, and learning to better cope with distress through mutual support.

Table 1.

Overview of the COURRAGE-PLUS intervention.

| Duration | Focus of the session | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Week 1 | Intro | 4 hours | Opening session – therapist gets to know the group and consults for hopes for counselling. The group sets the norms and rules to guide group conduct. Introduced to storybook project, and researchers are introduced as part of the team. |

| Week 2 | C | 3 hours | C elebrating survival – acknowledging women as survivors rather than victims |

| Week 3 | O | 3 hours | O ur knowledge and skills that have helped us to survive |

| Week 4 | U | 3 hours | U nderstanding the history of these knowledge and skills |

| Week 5 | R | 3 hours | R emembering the hardships we have been subjected to |

| Week 6 | R | 3 hours | R eframing and re-positioning ourselves with regards to the problems we have experienced |

| Week 7 | A | 3 hours | A ppreciating important people in our lives |

| Week 8 | G | 3 hours | G uarding and protecting what is valuable to us |

| Week 9 | E | 4 hours | E nvisioning the future – hopes, dreams and aspirations for the future |

| Week 10 | P | 3 hours | P lanning for the future – identifying strategies to achieve your future |

| Week 11 | L | 4 hours | L earning together – Training and strategies |

| Week 12 | U | 4 hours | U buntu – collective actions and collective power |

| Week 13 | S | 4 hours | S haring – ceremony to mark the end of the counselling journey |

In response to feedback from the initial unevaluated pilot of the COURRAGE method, the first author designed a set of four additional sessions (PLUS) to run alongside COURRAGE, with the aim to help women develop practical solutions to directly tackle the structural drivers of their mental distress, such as poverty and unemployment. In our pilot, this included training women in the use of priority setting tools, to identify priorities, goals and action needed to make changes in their lives. They also mapped and identified gaps in existing relationships and resources required to achieve their aims, and discussed vignettes of fictional female characters engaged in entrepreneurial and social development activities targeting sociostructural determinants of emotional distress. In the final session women received training in areas self-identified as meaningful to their collective and individual action plans. During the pilot, two training sessions were requested (1) advice and guidance on establishing social enterprises (2) setting up savings groups.

When combined, the intervention package presents a resource-oriented and strengths-based approach, highlighting women’s achievements, knowledge, and skills as a mechanism of moving beyond adversity and related trauma that drives their poor mental health outcomes. See Table 1 for an overview of the COURAGE-PLUS intervention.

Methods and materials

Participants and recruitment

Women experiencing complex levels of adversity including endemic poverty, exposure to everyday forms of violence, intimate partner violence and other forms of exclusion, were invited to participate. In Gauteng province, levels of social adversity commonly linked to poor mental health are high. As of August 2020, unemployment rates were recorded at 41% (Statistics South Africa, 2020) in the province, with women traditionally overrepresented in this category, (Statistics South Africa, 2019) with reports noting that nationally, women’s labour force participation levels have dropped by more than 5% in 2020 alone (Statistics South Africa, 2020). Gauteng also experiences high rates of crime, sexual and other forms of violence (Human & Geyser, 2020). These challenges are experienced against the backdrop of low or inadequate mental health service coverage in the province (Robertson and Szabo, 2017).

We used purposive sampling to recruit women living through these contexts and facing subsequent risks of depression, in order to understand the value of our intervention to this specific population. We worked in partnership with a South African NGO, Afrika Tikkun (AT), which specializes in providing community and wellbeing support for children and their families. Conversations with senior staff suggested that women involved in their support groups for mothers with children with disability experienced the most complex set of realities of interest in this study. Through this strategy, we were able to recruit, work with and support women who experience multiple forms of adversity: poverty, food insecurity, violence, caregiving in complex settings. This fit with our desire to explore the impact of this intervention for women living through general states of adversity.

Specific inclusion criteria included: women at the age of 18 or over, who were able to give consent for themselves and regularly attended Afrika Tikkun services at one of the four selected sites (see section 2.2 for details) within the last 2 months. Severity of participants’ depressive symptoms at screening was not included in criteria, to allow for an understanding of therapeutic effectiveness across a spectrum of subclinical and clinical depressive symptoms, and to provide benefit to as many vulnerable women as possible within the Afrika Tikkun community. Women were currently residing in South Africa, but about half were originally from Zimbabwe.

The study was presented by the senior author at meetings held at each participating Afrika Tikkun site, and participants were then encouraged to sign up for the intervention with the on-site social worker. At the initial session, the consent form was presented and discussed with participants, who provided written consent. Ethical approval was obtained from UCL [REC:16127/001] and the University of Johannesburg [REC-01-089-2019].

Women did not receive any financial incentives for participation. Sessions were held on days/times when women were already on site to avoid any additional costs to participants. In line with existing supports provided by the organisation, Women were given meals following each session. However, this was not mentioned at recruitment, to ensure that women’s participation was linked to a desire to promote wellbeing, rather than addressing food insecurity.

Study design and intervention

This pilot study used a non-randomised, repeated-measures design. COURRAGE-PLUS consisted of 13 sessions lasting 3 to 4 hours, delivered as weekly group meetings between September and December 2019. Women were placed in groups with 8 to 13 participants each. The meetings were hosted at four different branches of the local NGO Afrika Tikkun in the greater Johannesburg area. Sessions were delivered by teams of facilitators including a psychosocial practitioner from PHOLA, and the Afrika Tikkun auxiliary social worker based at each site. Each PHOLA facilitator was responsible for two sites. At two sites, research assistants participated in all sessions (as participant observers) to conduct an ethnographic process evaluation of the pilot.

All facilitators completed three days of training led by the first and senior author: two days of training on the intervention (sessions and aligned to delivery of intervention), and one on research related practices (informed consent, ethics, confidentiality, and the adverse event protocol). These sessions also allowed us to refine content of the intervention to increase its suitability an urban South African population. For example, facilitators worked in teams to re-write vignette used within the PLUS sessions). PHOLA facilitators were supervised by the first and senior author throughout the intervention. Any issues relating to participant mental health were escalated and supported through Afrika Tikkun services, in line with our protocol. Bi-weekly team update meetings were coordinated by the first author and attended by all facilitators and researchers. Assessments were conducted at three time points: Baseline, Post-COURRAGE (after week 9), and Post-Intervention (after week 13). Participants also completed life history interviews post-intervention to explore feasibility and acceptability, which will be reported elsewhere (Burgess et al.., forthcoming).

Outcomes and analysis

The severity of depressive symptoms was measured with the PHQ-9 (Patient Health Questionnaire), a self-administered depression screening tool consisting of nine items based on the diagnostic criteria for depression in the fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Kroenke et al., 2001). PHQ-9 has been validated and used extensively in the South African context (Bhana et al., 2015; Cholera et al., 2014) Depression severity was indicated by scores between 0 and 27, divided by five levels: Minimal (scores 0–4), Mild (scores 5–9), Moderate (scores 10–14), Moderately severe (scores 15–19), and Severe (scores ⩾20; Kroenke et al., 2001). We used a cut-off score of nine to determine presence of a major depressive disorder based on recent work in similar populations (Bhana et al., 2015). Given the varied levels of literacy among women in this study, the tool was administered by facilitators. This is in line with studies in similar settings (e.g. Bhana et al., 2015).

Median PHQ-9 scores and the corresponding interquartile range for the three time points (Baseline, Post-COURRAGE, and Post-Intervention) were calculated to offer descriptive information on the progression of participants’ depressive symptoms during the intervention. PHQ-9 scores, and associated depression severities, are usually non-normally distributed (Kocalevent et al., 2013), which informed our use of, median scores as they are more representative of non-normal distributions, and is in line with reporting in similar studies (Nicholas et al., 2019). Due to the distribution of scores and the sample size, non-parametric related samples analysis of variance by ranks (Friedman Test) was conducted to examine the overall significance of differences in PHQ-9 score distributions between our three time points. Subsequently, Dunn-Bonferroni post-hoc tests were employed for pairwise comparisons between time points and effect sizes (r) were calculated by dividing the corresponding z-statistics by (Field, 2018). IBM SPSS 26 was used for all analyses.

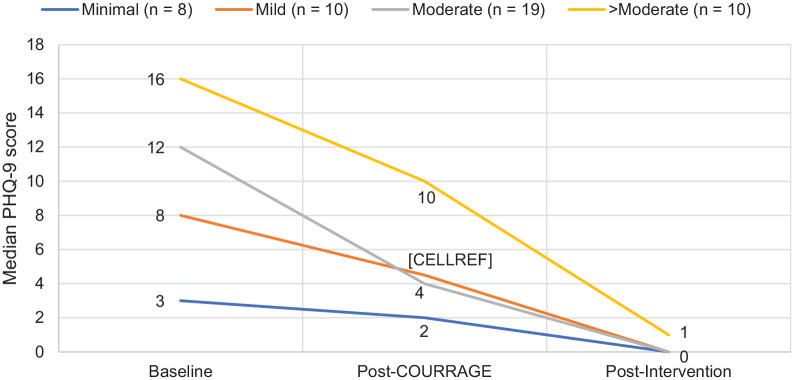

To further understand the overall effect of the intervention on depressive symptoms, the progression of depressive symptoms throughout the intervention was compared across different symptom severity categories. The PHQ-9 thresholds mentioned above were applied to create four symptom severity sub-groups (Minimal, Mild, Moderate and Moderately severe and above). For each group, the median at the three time points of measurement was determined and the progression compared with a line graph constructed in Microsoft Excel.

Results

Retention

In total, 47 women (mean age 37.23, SD = 9.51) participated our study. All women completed data collection at baseline. A total of 10 women had incomplete data sets, where one participant missed the midline timepoint, and nine participants missed the endpoint timepoint. According to facilitator reports, nine women missed the final session to attend a longstanding appointment linked to their children’s schooling. As a result, 37 women were included in our final analysis.

Reductions in depression scores

Findings indicate that across the intervention median PHQ-9 scores reduced substantially at each time point (Table 2). At Post-Intervention, the median PHQ-9 score was 0, as 24 of 37 participants (64.9%) noted scores of 0.

Table 2.

PHQ-9 scores throughout the intervention.

| n | Median (IQR) | |

|---|---|---|

| PHQ-9 scores | ||

| Baseline | 47 | 11 (7) |

| Post-COURRAGE | 45 | 4 (7) |

| Post-intervention | 37 | 0 (2.5) |

Note. PHQ-9 = patient health questionnaire (depression scale); IQR = interquartile range.

Friedman and post-hoc tests

The Friedman and post-hoc tests included participants with complete data across all time points (n = 36). The results showed a statistically significant difference between PHQ-9 scores at Baseline, Post-COURRAGE and Post-Intervention, (2) = 49.29, p < .001. The reduction in PHQ-9 scores was significant across all parts of the intervention between Baseline and Post-Intervention (p < .001), as well as between Baseline and Post-COURRAGE (p < .001), and Post-COURRAGE and Post-Intervention (p = .007). Effect sizes for the pairwise comparisons were large for the comparison between Baseline and Post-Intervention (r = .79) and medium for the between Baseline and Post-COURRAGE (r = .39) and Post-COURRAGE and Post-Intervention (r = .36).

Effect for different depression severities

Figure 1 shows that median PHQ-9 scores declined to 0 or 1 at Post-Intervention for all four symptom load groups independent of symptom severity at Baseline.

Figure 1.

Decline in PHQ-9 scores across four groups of symptom severity (n at baseline).

Discussion

Findings show that both components of the COURRAGE-PLUS intervention (collective narrative therapy and the social intervention) significantly reduced depression symptoms, across the spectrum of subclinical to moderately severe symptom severities, among a sample of women facing complex adversities in Gauteng province.

Current research indicates a relationship between poverty and mental ill-health in LMIC widely (Lund et al., 2018; Ohrnberger et al., 2020), and in South Africa (Lund & Cois, 2018). Debates remain over the most appropriate ways to tackle the complex interplay of poverty and mental ill-health. While some underline the positive socioeconomic effect of mental health interventions and thus propose to scale up biomedical mental health care in low- and middle-income settings (Lund et al., 2011), others advocate for a stronger focus on the societal drivers of inequality and poverty rather than on the ‘psychiatrisation’ and individualisation of mental distress associated with these drivers (Mills, 2015), demanding upstream changes to social, political and economic systems that reify and embed poverty within families, households and societies (Burns, 2015; Burgess et al., 2020; Rose et al., 2020)

However, such positions overlook the interconnected nature of poverty as something that is lived through; overlooking the ways in which cycles between social adversity and mental health are mutually reinforcing, and work to lock individuals within poor health and related social challenges. As such, interventions which respond to only one dimension, are neccessary but insufficient. COURRAGE-PLUS sought to accept and work at these intersections. Combining components that tackle psychological and emotional symptoms, while helping women identify new responses to the downstream impacts of poverty through social and economic skills development promoting entrepreneurial activity and engagement. To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate this combination in South Africa; collective narrative therapy has, to our knowledge, yet to be implemented or evaluated elsewhere, and very few studies have explored the specific ‘booster’ effects of combining social interventions within therapeutic work.

Other interventions have also successfully reduced symptoms of depression within a psychological intervention rooted in culturally relevant knowledge systems. For example, Nakimuli-Mpungu et al. (2020, 2014) group support psychotherapeutic intervention, in combining a social intervention with cognitive-behavioural group therapy, also draws on local cultural idioms of wellbeing and distress to anchor psychological therapy and psychiatric paradigms, and was successful at reducing poor mental health outcomes. However, given the different focus of their intervention (HIV-Depression) further comparisons between the two studies are not possible.

The COURRAGE intervention’s ability to work within a non-clinical community facing high levels of social adversity, without over-emphasising medicalised concepts of mental ill-health to the exclusion of social challenges faced within the community, is a novel approach in these settings. It also highlights the value of specified mental health support and prevention activities that work with people at risk for mental illness due to social and structural drivers, by addressing psychological sequalae before they develop into full blown illness, which has been championed elsewhere (McGorry and Nelson, 2016). Furthermore, we imagine the use of creative storytelling as a route to re-framing women’s lives in a narrative of survival also contributed to wellbeing and symptom reduction, supporting existing work linking these approaches to improved mental health in similar settings (Newland & Bettencourt, 2020)

There are potential limitations to our findings. First, because this is a one-armed pilot study, we are limited by our small sample size. Furthermore, without a comparison group, we cannot understand the intervention’s impact compared to other treatment modalities (i.e. pharmacological interventions). We will explore this in future studies particularly given the impact shown across severities. It is also possible that the therapeutic effect of the intervention could have been overestimated due to missing data. While 9 of the 10 missing datapoints were explained by facilitator reports, these same women also had significantly higher median depression scores (Median test, p = .014) at Post-COURRAGE time point, (Median = 14; IQR = 12) compared to the 36 participants who completed all data points (Median = 3.5; IQR = 5). As such, future work should further explore the impact of the intervention for women with more severe symptoms of depression. However, as all nine women were mothers of children with a disability, the higher depression could also be accounted for by the added mental health burden of caring for a disabled child (Bromley et al., 2004; Masefield et al., 2020). However, in an alternative, more conservative Friedman test (n = 45) substituting missing endline PHQ-9 scores with Post-COURRAGE/midline PHQ-9 scores (assuming no changes to these women), all three post-hoc comparisons remained statistically significant (baseline vs. endline: p < .001; baseline vs. Post-COURRAGE/midline: p = .029; Post-COURRAGE/midline vs. endline: p = .018). Thus, our findings are supported even when controlling for attrition.

Notwithstanding, our pilot study showed encouraging results in terms of effect of collective narrative therapy, and the feasibility of combining this approach with social intervention/development support. Future studies should evaluate impact using a controlled group, as well as a treatment comparison group, exploring its impact relative to other forms of treatment. Studies should also include further follow up measurements post-intervention to examine the durability of symptom improvement and explore any long-term effects on poverty and other socio-structural drivers of depression connected to new skills developed. If positive impacts are confirmed in future trials, COURRAGE-PLUS and similar collective narrative approaches to interventions could present an important alternative to IPT and CBT, which are the currently recommended psychological interventions for people living in adversity by the WHO (2017).

Conclusion

COURRAGE-PLUS effectively reduced depressive symptoms across the spectrum of symptom severities. Our findings are encouraging and supportive of the development of locally created and indigenous led options for interventions. In addition, it suggests the value of combining mental health and social interventions that relate to structural realities driving distress. We support calls for additional research and consideration in global mental health policy the development of more contextually appropriate mental health interventions that harness community knowledge and support systems, particularly for women living at the intersections of multiple forms of adversity.

Acknowledgments

This work is the product of a team of practitioners and researchers who have committed to the importance of ensuring mental health services meet the demands of complex lives. We would specifically like to acknowledge the contributions of our wider team, including: Ms. Khanyi Dhlamini, Ms. Nanna Dankwa, Ms. Malebo Ngobeni, Ms. Tebogo Konkobe, and Ms. Ashleigh Beukes. We would like to thank Ms. Ntombi Mahlaule and her team at Afrika Tikkun. We also would like to thank Ms. Farah Shebani for research assistant support, Save Act and the SA Federation for Mental Health for their in-kind support to our women’s group. We are indebted to the women who participated in the programme and inspired us with their own pathways to transformation.

Footnotes

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This project was funded by a grant from the Naughton/Clift Matthew Fund (2018-19), and received in-kind support from Project Ember, SHM Foundation.

ORCID iD: Rochelle A Burgess  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9749-7065

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9749-7065

References

- Albert P. (2015). Why is depression more prevalent in women? Journal of Psychiatry & Neuroscience, 40(4), 219–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhana A., Rathod S. D., Selohilwe O., Kathree T., Petersen I. (2015). The validity of the Patient Health Questionnaire for screening depression in chronic care patients in primary health care in South Africa. BMC Psychiatry, 15, 118. 10.1186/s12888-015-0503-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bromley J., Hare D. J., Davison K., Emerson E. (2004). Mothers supporting children with autistic spectrum disorders: Social support, mental health status and satisfaction with services. Autism: The International Journal of Research and Practice, 8(4), 409–423. 10.1177/1362361304047224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess R., Campbell C. (2014). Contextualising women's mental distress and coping strategies in the time of AIDS: A rural South African case study. Transcultural Psychiatry, 51(6), 875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess R. A. (2015). Supporting mental health in South African HIV-affected communities: primary health care professionals’ understandings and responses. Health Policy and Planning, 30(7), 917–927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess R. A., Jain S., Petersen I., Lund C. (2020). Social interventions: A new era for global mental health? The Lancet Psychiatry, 7(2), 118–119. 10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30397-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess R. A., Ahmad A., Niklas J., Ngobeni M., Konkobe T., Rasool S. (forthcoming). The COURRAGE to hope: understanding pathways to improving depression in contexts of adversity throuh collective narative therapy for social change.

- Burns J. (2015). Poverty, inequality and a political economy of mental health. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 24(2), 107–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cholera R., Gaynes B., Pence B., Bassett J., Qangule N., Macphail C., Bernhardt S., Pettifor A., Miller W. (2014). Validity of the patient health questionnaire-9 to screen for depression in a high-HIV burden primary healthcare clinic in Johannesburg, South Africa. Journal of Affective Disorders, 167, 160–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper S. (2016). Global mental health and its critics: moving beyond the impasse. Critical Public Health, 26(4), 355–358. 10.1080/09581596.2016.1161730 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Field A. (2018). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics (5th ed.). SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Flores E., Fuhr D., Bayer A., Lescano A., Thorogood N., Simms V. (2018). Mental health impact of social capital interventions: A systematic review. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 53(2), 107–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gearing R., Schwalbe C., MacKenzie M., Brewer K., Ibrahim R., Olimat H., Al-Makhamreh S., Mian I., Al-Krenawi A. (2012). Adaptation and translation of mental health interventions in Middle Eastern Arab countries: A systematic review of barriers to and strategies for effective treatment implementation. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 59(7), 671–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Human R., Geyser M. (2020). Major interpersonal violence cases seen in a Pretoria academic hospital over a one-year period, with emphasis on community assault cases. African Journal of Emergency Medicine, 10(2), 81–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob K. S. (2014). DSM-5 and culture: The need to move towards a shared model of care within a more equal patient–physician partnership. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 7, 89–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson S. (2017). Social interventions in mental health: A call to action. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 52, 245–247. 10.1007/s00127-017-1360-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser B., Jo Weaver L. (2019). Culture-bound syndromes, idioms of distress, and cultural concepts of distress: New directions for an old concept in psychological anthropology. Transcultural Psychiatry, 56(4), 589–598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kienzler H. (2020). ‘“Making Patients” in postwar and resource-scarce settings. diagnosing and treating mental illness in Postwar Kosovo’. Medical Anthropology Quarterly, 34(1), 59–76. 10.1111/maq.12554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kocalevent R.-D., Hinz A., Brähler E. (2013). Standardization of the depression screener patient health questionnaire (PHQ-9) in the general population. General Hospital Psychiatry, 35(5), 551–555. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2013.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K., Spitzer R. L., Williams J. B. (2001). The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(9), 606–613. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q., He H., Yang J., Feng X., Zhao F., Lyu J. (2020). Changes in the global burden of depression from 1990 to 2017: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease study. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 126, 134–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund C., Brooke-Sumner C., Baingana F., Baron E. C., Breuer E., Chandra P., Haushofer J., Herrman H., Jordans M., Kieling C., Medina-Mora M. E., Morgan E., Omigbodun O., Tol W., Patel V., Saxena S. (2018). Social determinants of mental disorders and the Sustainable Development Goals: A systematic review of reviews. The Lancet Psychiatry, 5(4), 357–369. 10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30060-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund C., Cois A. (2018). Simultaneous social causation and social drift: Longitudinal analysis of depression and poverty in South Africa. Journal of Affective Disorders, 229, 396–402. 10.1016/j.jad.2017.12.050 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lund C., de Silva M., Plagerson S., Cooper S., Chisholm D., Das J., Knapp M., Patel V. (2011). Poverty and mental disorders: breaking the cycle in low-income and middle-income countries. The Lancet, 378(9801), 1502–1514. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60754-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masefield S. C., Prady S. L., Sheldon T. A., Small N., Jarvis S., Pickett K. E. (2020). The caregiver health effects of caring for young children with developmental disabilities: a meta-analysis. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 24(5), 561–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGorry P., Nelson B. (2016). Why we need a transdiagnostic staging approach to emerging psychopathology, early diagnosis, and treatment. JAMA Psychiatry, 73(3), 191–192. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.2868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills C. (2015). The psychiatrization of poverty: Rethinking the mental health-poverty nexus. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 9(5), 213–222. 10.1111/spc3.12168 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mills C., Fernando S. (2014). Globalising mental health or pathologising the global south? Mapping the ethics, theory and practice of global mental health. Disability and the Global South, 1(2), 188–202. [Google Scholar]

- Nakimuli-Mpungu E., Musisi S., Wamala K., Okello J., Ndyanabangi S., Birungi J., Nanfuka M., Etukoit M., Mayora C., Ssengooba F., Mojtabai R., Nachega J. B., Harari O., Mills E. J. (2020). Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of group support psychotherapy delivered by trained lay health workers for depression treatment among people with HIV in Uganda: A cluster-randomised trial. The Lancet Global Health, 8(3), e387–e398. 10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30548-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakimuli-Mpungu E., Wamala K., Okello J., Alderman S., Odokonyero R., Musisi S., Mojtabai R., Mills E. J. (2014). Outcomes, feasibility and acceptability of a group support psychotherapeutic intervention for depressed HIV-affected Ugandan adults: A pilot study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 166, 144–150. 10.1016/j.jad.2014.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Newland P., Bettencourt B. (2020). Effectiveness of mindfulness-based art therapy for symptoms of anxiety, depression, and fatigue: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice, 41, 101246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholas J., Ringland K., Graham A., Knapp A., Lattie E., Kwasny M., Mohr D. (2019). Stepping up: Predictors of ‘Stepping’ within an iCBT stepped-care intervention for depression. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(23), 4689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohrnberger J., Anselmi L., Fichera E., Sutton M. (2020). The effect of cash transfers on mental health: Opening the black box – A study from South Africa. Social Science & Medicine, 260, 113181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel V., Chowdhary N., Rahman A., Verdeli H. (2011). Improving access to psychological treatments: Lessons from developing countries. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 49(9), 523–528. 10.1016/j.brat.2011.06.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rees S., Silove D., Chey T., Ivancic L., Steel Z., Creamer M., Teesson M., Bryant R., McFarlane A., Mills K., Slade T., Carragher N., O’Donnell M., Forbes D. (2011). Lifetime prevalence of gender-based violence in women and the relationship with mental disorders and psychosocial function. JAMA, 306(5), 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridley M., Rao G., Schilbach F., Patel V. (2020). Poverty, depression, and anxiety: Causal evidence and mechanisms. Science, 370(6522), 1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson L. J., Szabo C. P. (2017). Community mental health services in Southern Gauteng: An audit using Gauteng District Health Information Systems data. The South African Journal of Psychiatry, 23, 1055. 10.4102/sajpsychiatry.v23i0.1055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Rönnblad T., Grönholm E., Jonsson J., Koranyi I., Orellana C., Kreshpaj B., Chen L., Stockfelt L., Bodin T. (2019). Precarious employment and mental health: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 45(5), 429–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose N., Manning N., Bentall R., Bhui K., Burgess R., Carr S., Cornish F., Devakumar D., Dowd J., Ecks S., Faulkner A., Ruck Keene A., Kirkbride J., Knapp M., Lovell A., Martin P., Moncrieff J., Parr H., Pickersgill M., . . . Sheard S. (2020). The social underpinnings of mental distress in the time of COVID-19 – Time for urgent action. Wellcome Open Research, 5, 166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statistics South Africa. (2019). Inequality trends in South Africa: A multidimensional diagnostic of inequality. Retrieved from January 19, 2021, from <http://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/Report-03-10-19/Report-03-10-192017.pdf>.

- Statistics South Africa. (2020). Statistical release. Quarterly labour force study: Quarter 3. Retrieved January 19, 2021, from <http://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0211/P02113rdQuarter2020.pdf>

- Summerfield D. (2013). “Global mental health” is an oxymoron and medical imperialism. BMJ, 346, f3509. 10.1136/bmj.f3509 [DOI] [PubMed]

- White M. (2003). Narrative practice and community assignments. International Journal of Narrative Therapy and Community Work, 2003(2), 17–55. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation. (2017). Scalable psychological interventions for people in communities affected by adversity: a new area of mental health and psychosocial work at WHO. Retrieved January 19, 2021, from https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/254581 [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation. (2020). Depression. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression

- Zhou D., Chiu Y., Lo T., Lo W., Wong S., Leung C., Yu C., Chang Y., Luk K. (2020). An unexpected visitor and a sword play: A randomized controlled trial of collective narrative therapy groups for primary carers of people with schizophrenia. Journal of Mental Health. Advance online publication. 10.1080/09638237.2020.1793123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]