Abstract

Bibliotherapy, particularly when supplemented with therapist contact, has emerged as an effective treatment for anxiety symptoms in children. However, its effectiveness in treating specific phobias in young children has been explored in only one study which targeted nighttime fears. The current study tested a novel bibliotherapy for fears of dogs in four to seven-year-old children. The therapy was conducted over four weeks and was supplemented with brief, weekly videoconference calls with a therapist. A non-concurrent multiple baseline design was used to evaluate the effectiveness of this treatment in a sample of seven children between four and seven years of age. Significant reductions in specific phobia diagnostic severity, parent and child fear ratings, and child avoidance during a behavioral approach task were all observed. Additionally, treatment adherence, retention, and satisfaction were all high. Future research is needed to replicate the findings in larger, more heterogeneous samples and to explore possible predictive variables; however, this study provides initial support for bibliotherapy as a non-intensive, first-line intervention for specific phobias in young children.

Keywords: Anxiety, Specific phobias, Dog phobias, Children, Bibliotherapy

Highlights

The effectiveness of bibliotherapy for fears of dogs in young children was examined.

Treatment adherence, retention, and parent satisfaction were high.

Improvements in phobia severity, fear ratings, and child avoidance were observed.

Results support the use of bibliotherapy as a first-line intervention for phobias.

Introduction

Specific phobias are one of the most common problems faced by young children (Oar et al., 2019). Defined in the DSM-5 as persistent and interfering fear of a specific object or situation (American Psychiatric Association (2013)), specific phobias go above and beyond the typical fears common in early childhood and create significant distress, interference, and impairment for children and families. Additionally, studies have shown that these phobias are not only detrimental in children’s day to day lives but they also contribute to the development of additional anxiety disorders over time (De Vries et al., 2019; Lieb et al., 2016; Oar et al., 2019). As a result, early intervention in the form of evidence-based treatments may be fundamental to giving children the protection they need to avoid later additional psychiatric disorders. Although specific phobias have been found to be similarly prevalent, if not more prevalent in younger children than older children, there has been much less research conducted with young children (Egger & Angold, 2006).

For older children and adolescents, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) has been shown to be a “well-established,” evidence-based treatment for several anxiety disorders (Banneyer et al., 2018; Farrell et al, 2019). Furthermore, several studies have been conducted to examine various CBT-based treatment programs specifically designed for young children with fears and anxieties as well (e.g., Banneyer et al., 2018; Monga et al., 2015; Ruocco et al., 2016; Waters et al., 2009).

Regarding treating specific phobias in young children, a single case study conducted in 2017 by Kershaw et al. (2017) examined the efficacy of One-Session Treatment (Ollendick et al., 2009; Öst, 1989) for the treatment of a specific phobia of dogs in a 4-year-old child. This treatment incorporated play-based activities into 3 h of concentrated CBT in which child and parent were both involved. At the end of treatment, the child no longer met criteria for specific phobia. Additional studies have utilized non-concurrent, multiple-baseline, single-case designs to examine initial efficacy of treatment in small samples of preschool age children. For example, one study examined play-based, one-session treatment for specific phobia of dogs in four preschool aged children (Farrell et al., 2018). This study found that three of the four children no longer met criteria for specific phobia of dogs by the end of treatment and all four children evidenced clinically significant reductions in symptoms. Additionally, all the children demonstrated stable symptoms across varying multiple baselines prior to the intervention, suggesting that it was the intervention itself, not the simple passage of time or some confounding third variable, that resulted in the decrease in symptoms.

Bibliotherapy, which utilizes books and other print material to provide the instruction that would normally be provided by a therapist, is another treatment used for youth anxiety disorders. It is currently considered to be a “probably efficacious” intervention (see Davis et al., 2011). For children receiving bibliotherapy, parents are typically used as at-home therapist proxies. Bibliotherapy efforts range from simply educating people about a problem in a non-fiction, “how-to” book to incorporating evidence-based techniques within both fictional and nonfictional stories (Coffman et al., 2013).

In one of the first studies examining the efficacy of bibliotherapy for children’s anxiety disorders, Rapee et al. (2006) compared bibliotherapy (e.g., parents were provided a commercially available consumer book, “Helping Your Anxious Child: A Step-by-Step Guide”, and children were provided a companion workbook) to nine sessions of standard in-person group CBT and a waitlist condition in 6 to 12-year-old children with various anxiety disorders. Importantly, participants in the bibliotherapy condition had no contact with a therapist or any study personnel during treatment. The authors found that while bibliotherapy was more effective than the waitlist, the bibliotherapy condition was less effective than the standard group condition (i.e., about 25% of the children in the bibliotherapy condition versus about 60% of youth in the group CBT condition were free of their primary anxiety disorder at post-treatment). In a second study, Lyneham and Rapee (2006) supplemented the same bibliotherapy intervention utilized by Rapee et al. (2006) for 6 to 12-year-old children with therapist contact under three conditions (i.e., nine scheduled telephone calls between parent and therapist; nine scheduled emails from the therapist to the parent and then unlimited emails to answer any questions; parents allowed unlimited telephone or email contact with their therapist). Findings indicated that 58% of children across the conditions were free of their primary anxiety disorder at post-treatment assessment with the highest percentage of children being diagnosis free in the telephone condition (89%). Similar results were found by Cobham (2012) when 95% of 7 to 14-year-old children who received therapist-supported bibliotherapy (i.e., parents attended a two-hour group training session and were given one parent- and one child-focused workbook to complete at home while participating in phone calls every other week) were anxiety diagnosis free following treatment and this number did not statistically differ from the children who received 12 session of in-person, individual, family-focused CBT. Collectively these studies demonstrate that bibliotherapy for children is likely more effective when supplemented with therapist-parent contact. Furthermore, bibliotherapy may be ideal for families who cannot receive standard services (i.e., due to lack of access, financial concerns, or time constraints) and may function as a low-intensity intervention in a stepped care approach to treatment (Ollendick et al., 2018).

Comparatively few studies have focused specifically on the treatment of specific phobia in young children. However, Uncle Lightfoot (Coffman (1981–1987)) a children’s book that is based on cognitive behavioral principles and includes exposure games embedded in the story, has been tested, revised, and retested over a number of years for the treatment of fear of the dark. After early experiments (Mikulas et al., 1986; Mikulas & Coffman, 1989) with 89 young children between the ages of 4 and 7-years-old, suggested that the book held promise as a treatment for fear of the dark, a later independent study (Santacruzet al., 2006) examined the treatment effects between Uncle Lightfoot (i.e., bibliotherapy/games), in vivo exposure, and a waitlist control over five weeks on fears of darkness in 78 children, ages 4 to 8. This study found that both active treatment conditions resulted in significant fear reductions compared to the waitlist control. In another study (Lewis et al., 2015), Uncle Lightfoot, Flip That Switch (i.e., the 2012 edition of Uncle Lightfoot; Coffman, 2012−2020) was used to treat nine children who had been diagnosed with a specific phobia of darkness. This study found that eight of the nine children had significant reductions in fear and significant increases in nights spent in their own bed, with symptom stability across multiple baselines prior to treatment (Lewis et al., 2015). After Uncle Lightfoot, Flip That Switch was translated into Hungarian, it was compared with a waitlist group in a sample of 73 children, ages 3 to 8, who evidenced varying levels of fear, from mild to severe (Kopsco et al., 2021). Although the dosage (i.e., amount the book was read) in this study was considerably lower than in the Lewis et al. (2015) study and many of the children were less fearful than those in the Lewis et al. (2015) study, the results supported previous findings of the efficacy of the Uncle Lightfoot book and games approach, which was delivered via parents. Nighttime adaptive behavior and darkness phobia symptoms improved significantly in the intervention group and the authors found that the more time dedicated to the exposure games the greater the increase of nighttime adaptive behaviors. Interestingly, parents of children who had the most intense fears reported greater post-treatment satisfaction with the treatment.

The current pilot study aimed to provide preliminary evidence regarding whether an intervention similar to Uncle Lightfoot (i.e., fictional children’s book and activities) could be applied to the treatment of specific phobias of dogs in 4 to 7-year-old children. It was hypothesized that children would demonstrate stable symptoms across multiple baseline sessions prior to treatment but would demonstrate significant reductions in symptom severity throughout treatment and at post-treatment and follow-up assessments. Additionally, it was hypothesized that this treatment would be acceptable to children and their families.

Method

Participants

Study participants included seven children ages 4 to 7-years-old (mean = 5.0-years) who met diagnostic criteria for a specific phobia of dogs. Four of the seven participants were male; five were Caucasian and two were Hispanic; all lived in two parent homes; and all had at least one parent who had an advanced education degree. Children’s receptive language abilities (PPVT-4; Dunn & Dunn, 2007) fell in the average and moderately high ranges (M = 117.86, SD = 11.34). Their expressive language abilities (EVT-2; Williams, 2007) fell in the average to extremely high ranges (M = 121.71, SD = 15.02). For five of the seven children specific phobia of dogs was the only disorder for which diagnostic criteria were met. The remaining two children also met diagnostic criteria for other anxiety disorders (i.e., separation anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, other specific phobias). Although one of the seven families did have a pet dog living in their home, the child reportedly avoided contact with this dog and remained highly fearful.

Study Design and Procedure

The current study was conducted under the approval of the [Masked for Review] Institutional Review Board (IRB # Masked for Review). Families were recruited via flyers in the community (an incorporated, university town in a rural county) and advertisements on local listservs. Interested parents (N = 9) completed a brief phone screen with a research associate to determine probable eligibility (i.e., presence of significant fear of dogs, absence of autism spectrum disorder and intellectual disability, not currently in treatment for the phobia or a related anxiety disorder).

Informed consent and verbal assent were obtained during the family’s first assessment session at the clinic. At this session, parents completed a diagnostic interview and questionnaires regarding their child’s fear of dogs and general psychopathology. All children also completed a short interview about their fear of dogs, a behavioral approach task, and measures of receptive and expressive language. Consistent with recent literature, the current study utilized a non-concurrent, multiple baseline design. Following the first session, families were randomized to a three- or four-week baseline waiting period during which parents and children submitted ratings of the child’s fear of dogs once per week. This baseline period was used to assess the stability of children’s fear over time. Baseline data, when combined with replication, has been found useful in gaining preliminary information during the initial development of novel treatments (Barlow et al., 1984; Lewis et al., 2015; Ollendick et al., 2018). A multiple baseline was the design of choice because it controls for the primary weakness (i.e., threat to validity) associated with changes related to using just one time phase. The multiple baseline design provides replication of phase changes through more than one series (see Barlow et al., 1984).

After this baseline period, families were scheduled to enter the treatment phase of the study. Two of the nine families declined to begin treatment at this time (i.e., one child’s fear had reportedly improved; one parent had time constraints). Following this, families were mailed the child book and a parent guidebook (see below) so that they were received prior to their first videoconference session. The books were accompanied by a letter encouraging the parents to begin reviewing the parent guidebook but requesting that they not begin reading the book to their child until after their first videoconference session.

During the treatment phase, parents met once a week with their assigned therapist via videoconference (see below) for a total of four 15-to-20-minute sessions. Each week, parents and children continued to submit ratings of the child’s fear of dogs. Additionally, parents completed a log of their child’s interactions with dogs and details regarding their reading of the treatment book. Although treatment has been recommended to be at “full force” when a treatment phase begins (Barlow et al., 1984), because a book was being read to the child over a period of four weeks, leading to increasing levels of exposure across treatment, the expectation was that the improvement in scores after baseline would occur on a more gradual treatment slope than would occur if the child were given a potent, full-strength intervention at the first treatment data point.

Both one week and three months following their last videoconference session, families returned to the clinic for follow-up assessments. At these sessions, parents completed an abbreviated diagnostic interview and assorted questionnaires while children completed a short interview about their fear of dogs and the behavioral approach task (see below).

Treatment

Cognitive behavioral bibliotherapy was delivered via an unpublished 9-chapter, 66-page story book entitled “Addie and that Rambunctious Dog: From Fear to Friendship” (Masked for Review). Addie, the main character in the book, had a specific phobia of dogs and learns to overcome her fears and to develop friendships with various dogs in various settings (e.g., friend’s home, walking in the neighborhood, the playground, and at an animal rescue shelter). The spiral-bound book was written specifically for this study and includes chapters oriented around specific information about dogs and their habits as well as a set of specific activities Addie could engage in to overcome her fear (e.g., approaching dogs, petting them, leading them, playing ball with them, and feeding them). These activities were designed to parallel exposure activities delivered in standard in vivo exposure treatments for a specific phobia of dogs.

Cognitive behavioral techniques embedded into the story include reframing the child’s thoughts that include catastrophic thinking or exaggeration, the modeling of verbal and tangible reinforcement for behavioral approach tasks, and exposing the child visually to a desensitization-like hierarchy of scenes that show a child’s modeling appropriate behavior in her interactions with dogs. Below is an example of the dialogue in Addie and That Rambunctious Dog manuscript and the scene that occurs after she and her dad were watching dogs in the park. Addie is just beginning to challenge her catastrophic thinking:

“After watching the children and dogs playing for a couple of hours, Dad asked, “Addie, do you think all dogs might be really mean and eat you up?” Addie thought about the question. “No, Dad. I didn’t see any really mean dogs. There was one dog that growled. He acted like he was going to bite. That was because another dog was trying to steal his food. I also saw that dogs play a lot like children play. Sometimes dogs play kind of rough, but so do my friends sometimes…” (p. 15)

All the illustrations (one for each of the 66 pages) are in color and were created by a professional artist, Dianne Dusevitch. The story involves a Caucasian child but includes diverse characters and illustrations in the book (e.g., African American child and adult; Hispanic child and Hispanic mother). Although the reading level of Addie and That Rambunctious Dog is Grade 3.3 on the Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level, parents were advised to read the book to their child at least twice, even if the child could read, before allowing the child to read it alone.

Parents were provided a 14-page guidebook that directed them on reading the book, setting up specific exposure activities, rewarding their child for engaging in the activities, and celebrating the successes of their child. They were encouraged to “try to spend at least several hours a week reading the book and participating in the activities that your child is willing to complete”. The parent guidebook requires an 8.3 grade level in reading skills (Flesch-Kincaid), making the materials potentially useful to a broad population. The parent guidebook provides 16 parent-child games/activities, an average of 1.8 activities per chapter. One of the early activities is for the parents to let the child observe dogs from the safety of a car, or through a store window. Later, in another activity the parent is asked to have the child come in supervised contact with dogs, beginning with newborn puppies and ending with a large dog. Parents were not provided with explicit instructions on how to find dogs but were encouraged to consider various options: dogs owned by extended family members, neighbors, and friends; dogs at pet stores, breeders, and animal shelters; dogs at the park or other recreation areas.

The stated goal was to read the entire book at least twice during the 4-week period and to complete the activities associated with each chapter. Importantly, children engaged in specific activities like those in the book but only when the child willingly agreed to do so. If the child was not ready to engage in certain activities, they were asked to perform activities they were previously able to accomplish and then to try the new, more difficult activities.

Each family was assigned a master’s-level therapist and during this four-week treatment phase the clinician called the parents weekly to discuss how their child was doing and if they had any questions about implementing the activities. These videoconference calls lasted 15–20 min on average. Therapists were instructed to provide support for parents and to reinforce information provided in the guidebook as appropriate (e.g., help parents problem-solve any difficulties they had completing the activities). The therapists attended weekly, group supervision meetings with a doctorate-level clinician to ensure adherence to the CBT principles outlined in the parent guidebook and review any difficulty addressing parents’ concerns.

Measures

Anxiety disorders interview schedule for DSM-5, parent version (ADIS-P; Silverman & Albano, 1996)

The ADIS-P is a semi-structured diagnostic interview which assesses for the presence of a variety of anxiety and non-anxiety related disorders. Following the interview, clinicians provide a Clinician Severity Rating (CSR) on a 9-point scale (0–8) for each disorder for which symptoms are endorsed. Higher scores indicate greater symptom severity and a score of four or higher is used to indicate that a clinical level of severity is present. Previous versions of the ADIS (i.e., for DSM-IV and DSM-III-R) have been found to possess good to excellent interrater and test-retest reliability (Lyneham et al., 2007; Silverman et al., 2001). In the current study, the complete ADIS-P was administered to parents at the initial assessment session and the disorders endorsed at this session were re-assessed at the post-treatment and three-month follow-up sessions. Assessors were graduate students enrolled in a clinical science program and advanced undergraduate research assistants trained to reliability via co-coding of previously recorded ADIS administrations. CSR inter-rater reliability estimates (ICCs) from prior projects from the current lab which utilized the same training approach ranged from 0.48 to 0.96 indicating fair to excellent reliability.

Behavioral approach task (Ollendick et al., 2009; Öst et al., 2001)

The Behavioral Approach Task (BAT) was designed to measure children’s approach and avoidance behaviors when exposed to a dog in vivo in the clinic. Each child was taken to the hallway outside of a closed room and told that there was a friendly dog being held on a leash by one of our assistants on the opposite side of the room. They were instructed: “I want to see if you can go into the room, walk up to the dog and pet it on the head for about one minute. I want you to try your best, but you only have to do as much as you like”. A few minutes after completing the task alone, each child completed the task a second time with a parent present. Parents were told that they were free to help their child as much as they would like. Each child’s approach behavior was rated by the clinician on an 11-point scale on which each step was labeled and represented increased approach behavior (e.g., 0 = does not open door; 3 = Enters room, takes 1–3 steps toward the dog; 7 = Reaches out to dog but does not actually touch/pet it; 10 = Pets dog for full 60 seconds). The BAT was completed at the pre-treatment, one-week post-treatment, and three-month post-treatment assessment sessions. The same dog was used for all seven children and at each time point.

Specific phobia of dogs fear rating

Parents were asked to rate their child’s fear of dogs on an 11-point scale ranging from 0 (Not Afraid at All) to 10 (Extremely Afraid). Children were asked to rate their own fear of dogs on a five-point scale ranging from 0 (Not at All) to 4 (Very Much). For the children, each number was accompanied by a face displaying gradually increased levels of fear. Children rated their fear of “little” dogs, “mid-sized” dogs, and “big” dogs separately. Fear ratings from parents and children were obtained at the initial assessment session, once per week during the baseline period, once per week during the treatment period, and at the post-treatment and follow-up assessments. The child’s highest of the three size-based fear ratings at each time point was used for analyses in the current paper.

Section 2.4.4 adaptive behavior scale for dog approach behaviors

The My Child’s Interactions with Dogs (MCID) instrument serves as an adaptive behavior scale for dog approach behaviors. It asks the parent to report on the child’s behavior “at this time” for a series of 42 behaviors involving dogs. Possible responses are “Yes, easily,” “Yes but with difficulty” and “No”. The items cover a range of situations, from the child’s observing dog pictures in a book or watching dogs pass by the window, to situations that require the child to pet, walk, or play with a dog. While the laboratory BAT is designed to measure on-site behaviors as the child approaches a medium-sized dog, the MCID is designed to assess naturalistic situations with a number of different dogs in different settings (e.g., home, park, neighborhood). The questions on Section C of the MCID are very specific. For example, one item states “If there is a dog on a leash, my child can continue to walk down the street with me if the dog is 10 feet away”. Another item states, “My child can spend the night with a friend who has a dog”. Items require the parent to respond based on three sizes of dogs: small, medium, large. Total scores range from 0 to 84 with higher scores indicating increased ability to interact with dogs of various sizes in various settings. A Pearson Product Moment Correlation revealed a one-week test-retest reliability of 0.97 based on Baseline 1 and Baseline 2 comparisons and a three-week test-retest reliability of 0.858 on Baseline 1 and 4 comparisons.

Treatment satisfaction

At the three-month follow-up assessment, parents completed a 9-item measure of treatment satisfaction. Items were answered on either a 9-point scale (0 = Not at all, 8 = Very, very much; 3-items) or a 5-point scale (1 = Strongly disagree, 5 = Strongly agree; 6-items). Questions asked how the child’s fear and avoidance compared to same-age peers (9-point scale), how much the child’s phobia currently interfered in his/her life (9-point scale), how the program helped the parents learn about fears and cope better with their child’s phobia (5-point scale), and how effective they felt the treatment program was (5-point scale). Parents were also invited to write any qualitative comments they wished to share about their experience with the intervention.

Data Analyses

Because of the small sample size, data were analyzed using nonparametic tests. Friedman tests were conducted to examine changes in the ADIS-P CSRs, parent and child fear ratings, MCID total scores, and BAT steps completed across time. Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were used as post-hoc tests to explore significant differences between time points. Means and frequency counts were used to assess parent satisfaction.

Results

Treatment Adherence and Retention

During treatment, parents reported reading an average of 31 pages of Addie and That Rambunctious Dog and completing five activities per week. Although not all activities involved interacting with a dog (e.g., touching, petting, feeding a treat, giving a toy), families reported that on average their children interacted with a dog 2.33 times per week over the course of treatment. Qualitative information from parents about their children’s completion of activities and interest in the book throughout treatment are provided in Table 2. All seven families completed treatment and also completed the post-treatment assessment one week after the last video-conferencing session. Six of the seven families completed the three-month follow-up assessment. The family who did not complete the follow-up assessment did not respond to the clinic after three attempts were made to contact them. The child in this family did not differ from the other children at the pre- or post-treatment assessments and exhibited reductions in parent-report fear and clinician-rated phobia severity at post-treatment.

Table 2.

Parents’ Free Response Comments

| Comments During Treatment |

| Participant 1: “[Child] is interested since she has questions and likes the pictures, she can relate because she has a little brother, she was a little anxious when we got to the point of Addie petting the puppies, she did not like that idea”. “This week [Child] was able to pet a Chihuahua, she was afraid at the beginning but she did it two times while she was carried by myself and her father”. “[Child] likes the book and she looks forward to keep reading and she sometimes even remember about the book when we see dogs”. |

| Participant 2: “[Child] was able to pet some puppies that we visited. He got a little startled when they barked but did well. They were six weeks old and I think pit bulls. The mother was outside at the time”. “[Child] has been very willing to try all the activities we have attempted so far”. “[Child] initiated petting a dog when we came across it unexpectedly”. |

| Participant 3: “She seems to already be more comfortable. We were able to go for a walk and two unknown dogs passed by. She did move away, but she did not stop or cry and we did not have to hold her… which was the norm!” “We were unable to find newborn puppies, but we looked at pictures, etc”. “Every day we drive by a fenced-in dog park that is near our house, so she sees dogs playing there daily. She likes to play “doggy”, where she pretends to be a dog. She has spoken fondly of dogs several times (e.g., “He’s so cute!”). She has watched movies involving dogs as main characters”. |

| Participant 4: “She seemed very happy to look at dogs and interacted with a small, calm dog. She was much less anxious than in the past”. “She was very excited to pet several dogs over the weekend. She also petted a very small puppy and large rottweiler at a t-ball practice and didn’t want to leave the dogs”. |

| Participant 5: “He was excited to pet several dogs at a food truck rodeo. He did not seem scared. They were small and big dogs”. |

| Participant 6: “[Child] pet a small dog numerous times”. “Will be completing some more activities with a planned encounter in the upcoming days”. |

| Participant 7: “One of the first times [Child] encountered a dog since starting the Addie book, he said “Here is a chance for me to be brave”. We were floored (and beaming with pride) when he said it, and now we re-use his phrase whenever he sees a dog”. “There were 3 dogs at a family birthday party over the weekend. [Child] was nervous, but didn’t run away, scream, or cry. He pet one of the small, calm dogs”. “We went to [pet store]. We looked at the puppies through the windows for a long time and discussed what they look like and what they were doing. Eventually, we asked to pet some dogs. He pet 2 small, calm puppies. He didn’t want to hold them. He tried to get him to pet an Alaskan Malamute, which was bigger and more energetic. He refused”. |

| Comments Regarding Overall Satisfaction |

| Participant 2: “I really liked the progressiveness of the treatment and how it set him up for success”. |

| Participant 4: “Very effective. Kids had a lot of fun and were very engaged in the process”. |

| Participant 7: “The story helped immensely!” |

| Note. Comments During Treatment were captured throughout the four weeks of intervention. |

Changes in Phobia Severity (Table 1)

Table 1.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Main Effects of Time for Treatment Outcome Measures

| Measure | Pre M (SD) |

Post M (SD) |

Follow-up M (SD) |

(χ2) | Effect Size (W) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parent CSR | 5.00 (0.82) | 2.86 (1.86) | 2.33 (1.97) | 10.21** | 0.851 |

| Parent Fear Rating | 7.67 (1.54) | 4.57 (3.05) | 3.50 (3.39) | 7.68* | 0.640 |

| Child Fear Rating | 3.00 (0.82) | 0.71 (1.25) | 1.00 (1.67) | 6.30* | 0.525 |

| BAT Steps Completed Alone | 5.57 (3.46) | 8.14 (3.24) | 9.33 (0.82) | 4.63 | 0.385 |

| BAT Steps Completed with Parent | 6.86 (3.44) | 9.43 (0.79) | 9.67 (0.52) | 6.86* | 0.571 |

| MCID Total | 21.98 (12.87) | 46.86 (27.03) | 57.17 (25.69) | 10.33** | 0.861 |

CSR Clinician Severity Rating, BAT Behavioral Approach Task, MCID My Child’s Interactions with Dogs; Effect size: >0.10 = small effect; >0.30 = medium effect; >0.50 = large effect

*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01

Analyses demonstrated a significant reduction in SP severity per the ADIS-P (χ2(2) = 10.21, p = 0.006, W = 0.85) across the assessment sessions. CSR means changed from 5.00 at pre-treatment, to 2.86 at post-treatment, and 2.33 at follow-up. Post-hoc Wilcoxon signed-rank tests found significant reductions in phobia severity from pre to post (Z = −2.23, p = 0.026), but not from post to follow-up (Z = −1.41, p = 0.157). At both the post-treatment and follow-up assessments three children no longer met diagnostic criteria for their SP (i.e., CSC < 4). Nonetheless, the CSRs were reduced for all seven children.

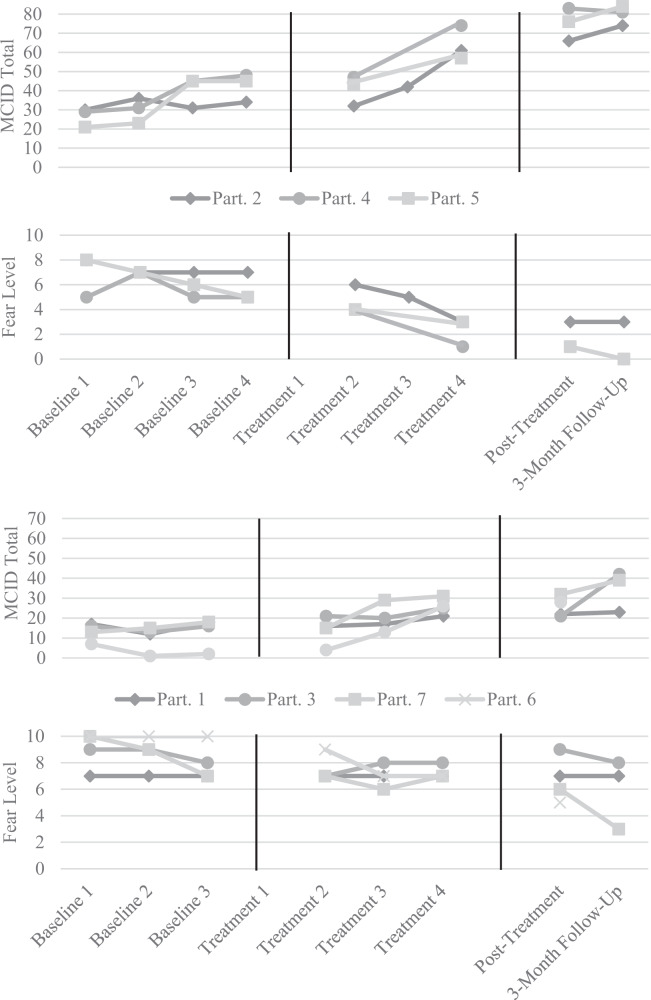

Changes in Parent Report of Fear (Fig. 1; Table 1)

Fig. 1.

Changes in Parent Report of Child Fear Levels and Dog Approach Behaviors across Time. Note. Parent rating of child fear and dog approach behaviors during pre-treatment baseline phase (3 or 4 weeks), during treatment, and at post-treatment and follow-up assessments. Range of possible fear ratings was 0–10; lower scores represent improvement. Range of possible MCID Total scores was 0 to 84; higher scores represent improvement. Participants 4 and 5 had identical fear ratings at the post-treatment and follow-up assessments (i.e., 1 and 0). Participants 1 and 3 had near identical MCID scores during the baseline sessions. Participant 6 did not complete the 3-month follow-up. Part. Participant, MCID My Child’s Interactions with Dogs

Results were similar for parent reported fear ratings. Analyses demonstrated a significant reduction in fear ratings (χ2(2) = 7.68, p = 0.021, W = 0.64). Means reduced from 7.66 on our 11-point scale at pre-treatment, to 4.57 at post-treatment, and 3.50 at follow-up. Post-hoc Wilcoxon signed-rank tests found significant reductions in fear ratings from pre to post (Z = −1.99, p = 0.046), but not from post to follow-up (Z = −1.89, p = 0.059). Furthermore, there was a significant correlation between parent-reported fear at the 3-month follow-up and total number of book pages read (r(4) = −0.78, p = 0.035).

Changes in Child Report of Fear (Table 1)

When child-reported fear ratings were explored, analyses also demonstrated a significant reduction in fear ratings (χ2(2) = 6.30, p = 0.043, W = 0.53). Means reduced from 3.00 at pre-treatment on our 5-point scale, to 0.71 at post-treatment, and then slightly increased to 1.0 at follow-up. Post-hoc Wilcoxon signed-rank tests found significant reductions in fear ratings from pre to post (Z = −2.23, p = 0.026), but no significant changes in fear from post to follow-up (Z = −0.27, p = 0.785).

Changes in Approach Behavior (BAT and MCID; Table 1)

Although improvements were noted in the child-alone BAT, results of a Friedman test demonstrated no significant reduction in avoidance between pre-treatment assessment to follow-up (χ2(2) = 4.63, p = 0.099, W = 0.39). Nonetheless, all but one child completed eight or more steps of the 10 step BAT at posttreatment and all six of the children who completed the follow-up assessment completed eight or more steps. In contrast, a Friedman test demonstrated that when completing the BAT with their parent, children demonstrated significant reduction in avoidance between the pre-treatment and follow-up assessments (χ2(2) = 6.86, p = 0.032, W = 0.57). At both the post-treatment and follow-up assessments all children completed at least 8 steps (i.e., petting the dog but discontinuing before 30 seconds) of the 10 possible steps Table 1.

Analyses also indicated a significant increase in MCID total scores from the pre-treatment to follow-up assessments (χ2(2) = 10.33, p = 0.006, W = 0.86). Post-hoc Wilcoxon signed-rank tests found significant increases in approach behaviors from pre to post (Z = −2.20, p = 0.028), but no significant changes from post to follow-up (Z = −1.78, p = 0.075).

Satisfaction Results

On average, parents reported being highly satisfied with the treatment and their child’s improvement. They reported that three months following treatment their children were between “a little bit fearful” and “somewhat fearful” compared to other kids their age (9-point scale; M = 2.83, SD = 2.56) and that their child’s fear interfered in his/her life between “not at all” and “a little bit” (9-point scale; M = 1.17, SD = 1.17). Additionally, five of the six parents reported that they “agreed” or “strongly agreed” with the statements that treatment helped them cope better with their child’s fear and that the treatment was helpful and effective. All six parents indicated that they “agreed” or “strongly agreed” that they would recommend the program to a friend whose child has a similar problem. Of the six parents, three chose to write additional comments on the satisfaction measure (see Table 2).

Discussion

The current pilot study explored the initial effectiveness of a therapist-supported bibliotherapy intervention for specific phobias of dogs in young children. While substantial evidence supports the efficacy of cognitive-behavioral treatments for specific phobias in school-aged children and adolescents (Davis et al., 2011; 2019), less research has explored whether these interventions are equally as effective for preschool and early elementary school aged children. Furthermore, to our knowledge, only two prior studies have utilized bibliotherapy to target young children’s specific phobias (Lewis et al., 2015; Santacruz et al., 2006). Although both studies supported the effectiveness of bibliotherapy, they exclusively targeted specific phobias of darkness.

Overall, the study hypotheses were confirmed; the therapist-supported bibliotherapy intervention was found to be acceptable to families and successful at reducing children’s fears of dogs. All seven families who began the intervention completed all four weekly videoconference sessions. Parents reported that they read approximately half of Addie and that Rambunctious Dog with their child each week and completed an assortment of the exposure activities described in the book and parent guidebook. Additionally, parent-reported satisfaction with the intervention was high. Clinician rated specific phobia severity, and both parent and child fear ratings, reduced following treatment and remained stable at the three-month follow-up assessment. Furthermore, the children’s avoidance of dogs decreased per parent report of their behavior in the community as well as during the behavioral approach task completed in the clinic. Following treatment all children could approach and pet an unfamiliar dog, whereas only three of the seven children could do so before treatment.

It is also important to note that visual inspection of the children’s fear levels across the baseline sessions (Fig. 1) confirms that the children’s fear levels were relatively stable prior to treatment. After the first week of treatment, six of the seven children’s fear ratings had reduced from their final baseline rating and the seventh child’s fear rating reduced following the second week of treatment. This confirms that the post-treatment changes in phobia severity and fear ratings was likely due to the intervention rather than to the sole passage of time.

Based on the responses of parents during the weekly videoconference calls, as well as written comments on forms (see Table 2), it appears that participants enjoyed the story. Although some parents reported some difficulty locating dogs, all eventually found creative ways to locate appropriate dogs (e.g., stores, hiking on park trails). Based on parental comments (Table 2), it also appears that parents understood from the children’s book or the parental instructions that it was important to help the child approach dogs in a progressive manner from less threatening to more threatening dogs (e.g., from small to large dogs). There did appear to be at least one reported instance in which the parent probably moved too quickly from success with a small dog to a large dog (a failed effort), suggesting the need to further clarify some of the instructions.

Despite promising reductions in the children’s specific phobia severity following the intervention, this pilot study is not without limitations and there are multiple domains in which future research can expand upon these findings. Importantly, the current sample was small and was largely homogenous: all children lived in intact families with highly educated parents, five of the seven children were Caucasian, and all children had average or above average receptive and expressive language abilities. As a result, the current findings may not generalize to more diverse samples. Particularly, given the nature of bibliotherapy, children’s language abilities may play an important role in their ability to internalize the information presented in the book. Additionally, parents’ education level likely influences the time and resources they have available to read with their children and complete the recommended activities. Qualitatively, a common challenge parents discussed during the videoconference sessions was their ability to identify and access appropriate dogs to expose their children to in vivo. This challenge may be more significant in families with fewer resources, which could subsequently hinder children’s progress. If a similar study is done in the future, researchers should consider identifying resources for participants, such as agencies with comfort dogs available or local veterinarians who may be able to help families locate dogs with which to practice exposure.

Future studies including larger, more diverse samples could identify for which children and families the intervention is most effective. Furthermore, parental psychopathology was not measured in the current study. However, parental psychopathology, particularly anxiety, could influence parents’ ability to facilitate their child’s exposure to dogs via the recommended activities and future studies should explore the influence of parental psychopathology on the implementation of bibliotherapy. Lastly, the assessors who completed the diagnostic interviews and assigned CSRs were not blind to the goals of the study and thus may have been biased in their ratings of improvement following treatment. Nonetheless, the assessors and therapist assigned to each family were distinct and no individuals served as both the assessor and therapist for the same family.

While all children experienced reductions in their specific phobia clinical severity rating and fear ratings from the initial baseline session to the three-month follow-up, at the three-month follow-up three of the six children continued to meet minimal diagnostic criteria for a specific phobia of dogs. Although it is possible that a longer-term follow-up would find that these children continue to improve, it is also possible that individual and familial differences could have reduced the effectiveness of the intervention. In addition to exploring these potential predictor variables, it is important that bibliotherapy continue to be viewed as a low-intensity, non-intrusive treatment method that can be increased for the children who do not experience clinically significant change in their phobia. These children should be recommended for further, more intensive treatment, using a stepped care approach (Ollendick et al., 2018).

Future studies may also want to examine the effectiveness of a higher dosage of the treatment. Following the four weeks the current book was used, 42.8% of the children no longer met the diagnostic criteria for their primary Specific Phobia. This remission rate is lower than that found in other studies that included therapist-supported bibliotherapy (Cobham, 2012; Rapee et al., 2006); however, those studies involved nine and twelve weeks of intervention, respectively. Considering that the current treatment only lasted for four weeks and that most traditional CBT treatments last from 8 to 16 weeks, it would be useful to determine how feasible it would be for families to engage in the reading and activities for a longer time and to determine how successful the book would be if used for a longer time. Notably, two of the bibliotherapy studies utilizing Uncle Lightfoot (Lewis et al., 2015; Santacruz et al., 2006) had shorter intervention windows (4 and 5-weeks, respectively) and high efficacy. Whereas children have opportunities to be exposed to darkness each day, and access to the dark is not impacted by family schedules or resources, families of children with specific phobias of dogs may benefit from a longer intervention duration in order to complete more exposure activities.

An additional area of future research is the precise content of the bibliotherapy book. Approximately 50% of children diagnosed with a specific phobia also meet criteria for a second phobia diagnosis (Ollendick et al., 2010) and research has demonstrated that CBT for a targeted specific phobia results in significant improvement in comorbid, non-targeted specific phobias (Ryan et al., 2017). However, whether this effect is also found for children who receive bibliotherapy has not yet been explored. The current study, as well as the two prior studies which targeted phobias of darkness, utilized phobia-specific children’s books: the stories and illustrations specifically discussed fears of dogs and fears of the dark, respectively. It is possible that these phobia-specific books will have generalized effects similar to phobia-specific CBT; however, if this is not empirically supported, development of a bibliotherapy book which targets phobias generally may allow for a larger degree of improvement in a subset of children.

In conclusion, the current pilot study provides initial support for the effectiveness of therapist-supported bibliotherapy for young children with specific phobias of dogs. Together with previous research involving children with specific phobias of darkness, these studies support the use of bibliotherapy as a first-line treatment for specific phobias in young children. This is especially promising for families who live in underserviced areas or who have other restrictions that would interfere with their ability to attend standard, in-person, weekly therapy sessions. Additionally, the use of bibliotherapy, supplemented with brief videoconference sessions with a therapist, is particularly relevant during the current Covid-19 pandemic as it provides an alternative treatment method for all families.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA.

- Banneyer KN, Bonin L, Price K, Goodman WK, Storch EA. Cognitive behavioral therapy for childhood anxiety disorders: a review of recent advances. Current Psychiatry Reports. 2018;20(8):65. doi: 10.1007/s11920-018-0924-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow, D. H., Hayes, S. C., & Nelson, R. O. (1984). The scientist practitioner: Research and accountability in clinical and educational settings. New York: Pergamon Press.

- Cobham VE. Do anxiety-disordered children need to come into the clinic for efficacious treatment? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2012;80(3):465. doi: 10.1037/a0028205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffman, M. F. (1981–1987). Uncle Lightfoot. Unpublished manuscripts.

- Coffman, M. F. (2012–2020). Uncle Lightfoot flip that switch: Overcoming fear of the dark. St. Petersburg, FL: Footpath Press LLC (D.C. Dusevitch, Illustrator).

- Coffman, M., Andrasik, F., & Ollendick, T. H. (2013). Bibliotherapy for anxious and phobic youth. In C. A. Essau & T. H. Ollendick (Eds.), The Wiley-Blackwell handbook of the treatment of childhood and adolescent anxiety (pp. 275–300). Wiley Blackwell.

- Davis TE, May A, Whiting SE. Evidence-based treatment of anxiety and phobia in children and adolescents: Current status and effects on the emotional response. Clinical Psychology Review. 2011;31(4):592–602. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis TE, Ollendick TH, Öst LG. One-Session treatment of specific phobias in children: Recent developments and a systematic review. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2019;15:233–256. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050718-095608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vries YA, Al-Hamzawi A, Alonso J, Borges G, Bruffaerts R, Bunting B, Esan O. Childhood generalized specific phobia as an early marker of internalizing psychopathology across the lifespan: Results from the World Mental Health Surveys. BMC Medicine. 2019;17(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12916-019-1328-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn, L. M. Dunn, D. M. (2007). PPVT-4: Peabody picture vocabulary test(4thed.). Minneapolis, MN: Pearson Assessments.

- Egger HL, Angold A. Common emotional and behavioral disorders in preschool children: presentation, nosology, and epidemiology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2006;47(3–4):313–337. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrell LJ, Kershaw H, Ollendick T. Play-modified one-session treatment for young children with a specific phobia of dogs: A multiple baseline case series. Child Psychiatry & Human Development. 2018;49(2):317–329. doi: 10.1007/s10578-017-0752-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrell, L., Ollendick, T. H., & Muris, P. (Eds.) (2019). Innovations in CBT treatment for childhood anxiety, OCD, and PTSD. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kershaw H, Farrell LJ, Donovan C, Ollendick TH. Cognitive behavioral therapy in a one-session treatment for a preschooler with specific phobias. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2017;31:7–22. doi: 10.1891/0889-8391.31.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopcsó, K., Láng, A., & Coffman, M. F. (2021). Reducing the nighttime fears of young children through a brief parent-delivered treatment—Effectiveness of the Hungarian version of Uncle Lightfoot. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lewis KM, Amatya K, Coffman MF, Ollendick TH. Treating nighttime fears in young children with bibliotherapy: Evaluating anxiety symptoms and monitoring behavior change. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2015;30:103–112. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2014.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieb R, Miché M, Gloster AT, Beesdo‐Baum K, Meyer AH, Wittchen HU. Impact of specific phobia on the risk of onset of mental disorders: A 10‐year prospective‐longitudinal community study of adolescents and young adults. Depression and Anxiety. 2016;33(7):667–675. doi: 10.1002/da.22487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyneham HJ, Abbott MJ, Rapee RM. Interrater reliability of the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV: child and parent version. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2007;46(6):731–736. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e3180465a09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyneham HJ, Rapee RM. Evaluation of therapist-supported parent-implemented CBT for anxiety disorders in rural children. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2006;44(9):1287–1300. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikulas WL, Coffman MG, Dayton D, Frayne C, Maier PL. Behavioral bibliotherapy and games for treating fear of the dark. Child and Behavior Therapy. 1986;7:1–7. doi: 10.1300/J019v07n03_01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mikulas, W. L., & Coffman, M. F. (1989). Home-based treatment of children’s fear of the dark. In C. E. Schaefer & J. M. Briesmeister (Eds.), Handbook of parent training: Parents as co-therapists for children’s behavior problems (pp. 179–202). John Wiley & Sons.

- Monga S, Rosenbloom BN, Tanha A, Owens M, Young A. Comparison of child–parent and parent-only cognitive-behavioral therapy programs for anxious children aged 5 to 7 years: Short-and long-term outcomes. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2015;54(2):138–146. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2014.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oar, E. L., Farrell, L. J., & Ollendick, T. H. (2019). Specific phobia. In S. N. Compton, M. A. Villabø, & H. Kristensen (Eds.) Pediatric Anxiety Disorders (pp. 127-150). San Diego, CA: Academic Press

- Ollendick TH, Öst LG, Farrell LJ. Innovations in the psychosocial treatment of youth with anxiety disorders: Implications for a stepped care approach. Evidence-based Mental Health. 2018;21(3):112–115. doi: 10.1136/eb-2018-102892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ollendick TH, Öst LG, Reuterskiöld L, Costa N, Cederlund R, Sirbu C, Jarrett MA. One-session treatment of specific phobias in youth: a randomized clinical trial in the United States and Sweden. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77(3):504. doi: 10.1037/a0015158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ollendick TH, Raishevich N, Davis III I. I. I. TE, Sirbu C, Öst LG. Specific phobia in youth: Phenomenology and psychological characteristics. Behavior Therapy. 2010;41(1):133–141. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2009.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Öst LG. One-session treatment for specific phobias. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1989;27(1):1–7. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(89)90113-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Öst LG, Svensson L, Hellström K, Lindwall R. One-session treatment of specific phobias in youths: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69(5):814. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.69.5.814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapee RM, Abbott MJ, Lyneham HJ. Bibliotherapy for children with anxiety disorders using written materials for parents: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74(3):436. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.3.436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruocco S, Gordon J, McLean LA. Effectiveness of a school-based early intervention CBT group programme for children with anxiety aged 5–7 years. Advances in School Mental Health Promotion. 2016;9(1):29–49. doi: 10.1080/1754730X.2015.1110495. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan SM, Strege MV, Oar EL, Ollendick TH. One session treatment for specific phobias in children: Comorbid anxiety disorders and treatment outcome. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 2017;54:128–134. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2016.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santacruz I, Méndez FJ, Sánchez-Meca J. Play therapy applied by parents for children with darkness phobia: Comparison of two programmes. Child & Family Behavior Therapy. 2006;28(1):19–35. doi: 10.1300/J019v28n01_02. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman, W. K., & Albano, A. M. (1996). Anxiety disorders interview schedule for DSM-IV: Child version. Oxford University Press.

- Silverman WK, Saavedra LM, Pina AA. Test-retest reliability of anxiety symptoms and diagnoses with the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV: child and parent versions. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;40(8):937–944. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200108000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters AM, Ford LA, Wharton TA, Cobham VE. Cognitive-behavioural therapy for young children with anxiety disorders: Comparison of a child + parent condition versus a parent only condition. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2009;47(8):654–662. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams, K. T. (2007). Expressive vocabulary test(2nded.). Minneapolis, MN: Pearson Assessments.