Abstract

In this contribution, we report chemoenzymatic bromodecarboxylation (Hunsdiecker-type) of α,ß-unsaturated carboxylic acids. The extraordinarily robust chloroperoxidase from Curvularia inaequalis (CiVCPO) generated hypobromite from H2O2 and bromide, which then spontaneously reacted with a broad range of unsaturated carboxylic acids and yielded the corresponding vinyl bromide products. Selectivity issues arising from the (here undesired) addition of water to the intermediate bromonium ion could be solved by reaction medium engineering. The vinyl bromides so obtained could be used as starting materials for a range of cross-coupling and pericyclic reactions.

Keywords: biocatalysis, Hunsdiecker reaction, decarboxylation, vinyl bromides, unsaturated carboxylic acids, vanadium chloroperoxidase

Introduction

Vinyl halides are versatile intermediates in organic chemistry, especially as starting materials in carbon–carbon cross-coupling reactions.1−3 Halodecarboxylation of α,β-unsaturated carboxylic acids represents a convenient synthetic access to a broad range of vinyl halides.4 In addition to the classical Hunsdiecker reaction5 starting from silver carboxylates and its later modifications such as the Cristol–Firth modification (utilizing HgO as a catalyst)6 and the Kochi reaction (utilizing stoichiometric amounts of Pb(OAc)4),7 some metal-free alternatives have been developed. The Barton reaction, for example, utilizes organic hypohalites as stoichiometric reagents,8 while the Suarez reaction is based on hypervalent iodosobenzene diacetates.9 More recently, N-halo succinimide (NXS)4,10 reagents have become dominant as a source for electrophilic halide species to initiate the halodecarboxylation reaction.

From an environmental and practical point of view, stoichiometric halide sources such as NXS10 or other N-halides11 may be questionable due to the formation of large amounts of succinimide waste products lowering the atom efficiency of the transformation and complicating product isolation and purification. Therefore, alternative methods for the in situ generation of electrophilic halides have been investigated comprising chemical12,13 or electrochemical halide oxidation14 methods. Particularly, vanadate15−18 and molybdate19 complexes have been investigated as mimetics for haloperoxidase enzymes. Their poor catalytic activity, however, necessitates high catalyst loadings of up to 10–50 mol %.

Already in 1985, Izumi and co-workers have pioneered an enzymatic approach for the oxidative generation of hypohalites with H2O2 and chloroperoxidase from Caldariomyces fumago (CfCPO) as a biocatalyst.20 Unfortunately, these pioneering contributions have not resulted in great interest from the research community, which can largely be ascribed to the difficulties using CfCPO as a catalyst.21,22 In addition to the issues in recombinant production of this catalyst, predominantly, it’s poor robustness against the stoichiometric oxidant (H2O2) represents a major practical hurdle.

With this in mind, we set out to evaluate whether the vanadium-dependent chloroperoxidase from Curvularia inaequalis (CiVCPO) may be a more suitable (bio)catalyst to promote H2O2-driven bromodecarboxylation reactions (Scheme 1). CiVCPO23−26 excels as a robust and active enzyme tolerating high concentrations of H2O2 and organic solvents. Overall, a chemoenzymatic reaction scheme was envisioned wherein CiVCPO catalyzes the H2O2-driven oxidation of bromide to hypobromite with the latter spontaneously (nonenzymatically) reacting with α,ß-unsaturated carboxylic acids yielding the corresponding vinyl bromide and CO2.

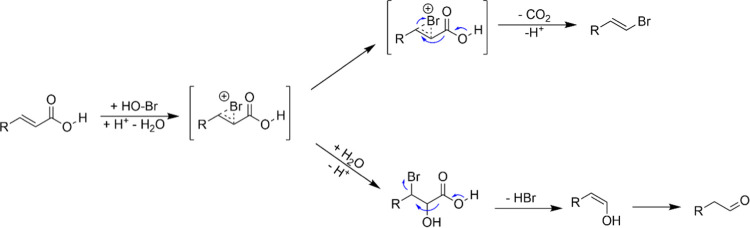

Scheme 1. Envisioned Biocatalytic Hunsdiecker-Type Reaction.

The overall reaction comprises a biocatalytic step in which the reactive halide species (hypohalite) is formed in situ from halides and H2O2 catalyzed by the V-dependent chloroperoxidase from C. inaequalis (CiVCPO). In the second step, the hypobromite spontaneously (nonenzyme-mediated) reacts with the starting material inducing the bromodecarboxylation reaction.

Results and Discussion

The biocatalyst (CiVCPO) was produced via heterologous expression in recombinant Escherichia coli following previously established procedures.25 Using p-coumaric acid (1a, 30 mM) as a model substrate, the desired product 4-(2-bromovinyl) phenol (1b) was readily obtained under the reaction conditions chosen initially ([CiVCPO] = 400 nM, [KBr] = 50 mM, [H2O2] = 30 mM, Figure 1). An initial reaction rate of 6.97 mM h–1 was observed (corresponding to a catalytic turnover frequency of the biocatalyst of 4.8 s–1). After approx. 6 h, a final yield of 82% (gas chromatography, GC yield) was obtained corresponding to 61,600 turnover number (TON) for CiVCPO. The reaction could be scaled up to 50 mL, resulting in 58% isolated yield (173 mg, Figures S1–S3). All relevant negative controls (i.e., performing the reaction in the absence of either CiVCPO or H2O2 or using thermally inactivated CiVCPO) failed to form any bromination products. Also substituting CiVCPO with a 25-fold excess of NaVO3 (under otherwise identical reaction conditions) did not give any decarboxylated product (Table S1).

Figure 1.

Time course of the chemoenzymatic decarboxylation of p-coumaric acid (●) (1a) to 4-(2-bromovinyl) phenol (▲) (1b). Conditions: [1a] = 30 mM, citrate buffer (100 mM, pH 5.0), [CiVCPO] = 400 nM, [KBr] = 50 mM, [H2O2] = 30 mM, 5% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), 30 °C, 1 mL. The data shown are the results from duplicate experiments.

Next, we investigated some key parameters (enzyme concentration, pH, H2O2 and KBr concentration) influencing oxidative decarboxylation in more detail (Table 1). The reaction rate correlated with the enzyme concentration (Table 1, entries 1–3). Increasing the concentration of H2O2 had a slightly negative effect on the product formation (Table 1, entries 3, 7–9). On one hand, the H2O2 concentration applied was significantly higher than the reported KM(H2O2) value for CiVCPO of ≪0.1 mM, which is why the catalytic activity of CiVCPO can be considered as being independent of the H2O2 concentration applied in these experiments. On the other hand, the rate of the hypobromite-initiated dismutation of H2O227 increases at increasing H2O2 concentrations and thereby decreases the in situ concentration of hypobromite and H2O2. In line with the reported pH optimum25 of CiVCPO, the highest catalytic rates were observed between pH 5 and 6 (Table 1, entries 3–6). An increase in the KBr concentration could lead to an increase in the reaction rate and product concentration (Table 1, entries 8 and 10), which we attribute to an increase in the in situ hypobromite concentration and the resulting acceleration of the chemical reaction step.

Table 1. Optimization of the Reaction Conditionsa.

| entry | c(CiVCPO) (nM) | pH | c(H2O2) (mM) | concn (mM) | initial rateb (mM h–1) | TONc | selectivityd (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 100 | 5 | 30 | 10.3 ± 1.1 | 3.80 | 10,2700 | 99 |

| 2 | 200 | 5 | 30 | 14.6 ± 1.6 | 5.68 | 73,200 | 99 |

| 3 | 400 | 5 | 30 | 24.6 ± 1.2 | 6.97 | 61,600 | 97 |

| 4 | 400 | 4 | 30 | 10.9 ± 1.9 | 2.95 | 27,100 | 96 |

| 5 | 400 | 6 | 30 | 19.6 ± 1.0 | 6.49 | 48,880 | 96 |

| 6 | 400 | 7 | 30 | 12.3 ± 0.1 | 4.03 | 30,600 | 94 |

| 7 | 400 | 5 | 50 | 23.5 ± 5.7 | 6.36 | 58,700 | 98 |

| 8 | 400 | 5 | 100 | 19.4 ± 0.4 | 3.14 | 48,000 | 98 |

| 9 | 400 | 5 | 200 | 21.6 ± 3.5 | 5.76 | 54,000 | 98 |

| 10 | 400 | 5 | 100e | 26.0 ± 0.7 | 7.95 | 65,000 | 97 |

Reaction conditions: [p-coumaric acid] = 30 mM, citrate buffer (100 mM, pH 4–5) or NaPi buffer (100 mM, pH 6−7), [CiVCPO] = 100–400 nM, [KBr] = 50–100 mM, [H2O2] = 30–200 mM, 30 °C, 5% DMSO, 6 h, 1 mL.

The initial rate is based on concentration of 1b at 3 h.

TON = Turnover number ([1b]/[CiVCPO]).

The selectivity was determined by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS). Selectivity = [1b]/([1b] + [1c]) × 100%.

[KBr] = 100 mM. A duplicate experiment was performed.

The highest formal CiVCPO activity observed in these experiments (i.e., initial rate divided by the biocatalyst concentration) was 10.5 s–1 (Table 1, entry 1), which is in line with CiVCPO activities previously observed (under comparable reaction conditions) ranging from 8.7 s–1 (in the case of Achmatowicz-type reactions)28 and 75 s–1 (as observed in the oxidative decarboxylation of glutamic acid).23 Bearing the chemoenzymatic character of these reactions in mind, the apparent differences in the formal CiVCPO activity most likely originate from different reactivities of the chemical starting materials with OBr–, suggesting the chemical step of the reaction sequence being overall rate-limiting.

It should be noted that in all experiments, some formation of p-hydroxyphenylacetaldehyde (1c, Figure S4, ranging between 0.04 and 0.81 mM corresponding to 0.3–6.2%) was observed. Presumably, nucleophilic attack of water to the intermediate bromonium ion leading to the aldehyde product was observed (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2. Proposed Nucleophilic Attack of Water to the Intermediate Bromonium Ion Competing with Its Decarboxylation.

As a phenolic staring material, some ring halogenation was expected to occur.29 Interestingly, only upon prolonged reaction times, traces of the ring-brominated vinyl bromide product were observed in the case of decarboxylation of 1a (Figure S4). Apparently, the conjugated C=C double bond reacted more readily than the aromatic ring system.

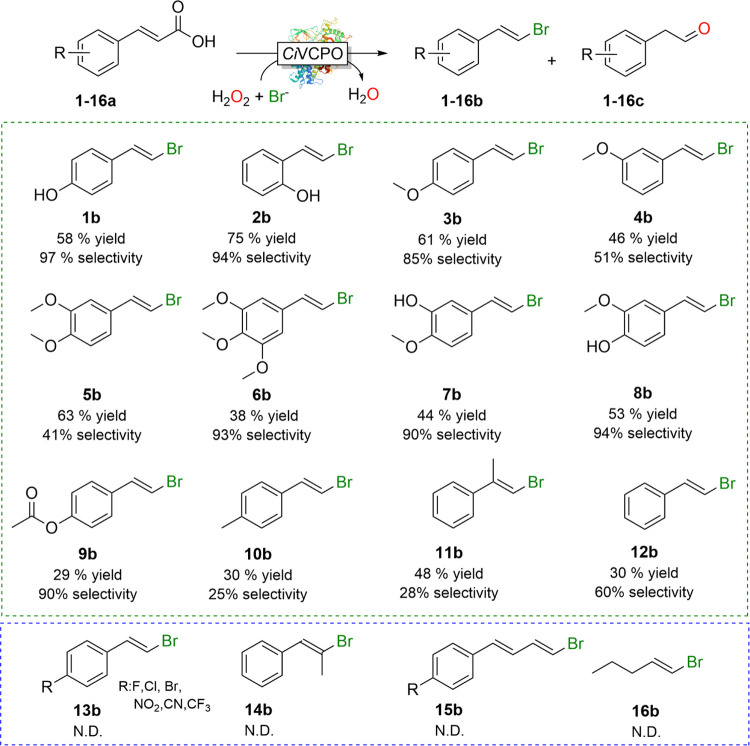

Next, we evaluated the substrate scope of the chemoenzymatic Hunsdiecker reaction in a 1.5 mmol scale by screening some commercially available substrates (Figure 2). Both substituted and nonsubstituted α,ß-unsaturated carboxylic acids could be transformed into the corresponding vinyl bromide products with good isolated yield (Figures S5–S37 and Table S2). Especially electron-donating substituted styrene derivates turned out to be good starting materials. Aromatic rings containing electron-withdrawing substituents such as halides, CN, CF3, or NO2 were not converted and the staring material was recovered. Also, for aliphatic α,ß-unsaturated carboxylic acids, no conversion was detectable under the experimental conditions applied here, which is in line with a previous report using CfCPO.20

Figure 2.

Substrate scope of preparative-scale chemoenzymatic decarboxylative bromination reaction. Conditions: [substrates] = 30 mM, citrate buffer (100 mM, pH 5), [CiVCPO]= 400 nM, [KBr] = 50 mM, [H2O2] = 30 mM, 30 °C, 10 h, 50 mL scale. 5–20% DMSO to improve the substrate solubility. Isolated yield was calculated after the purification. The selectivity was determined by GC–MS using 5% DMSO in the reaction. Yield means isolated yield. Selectivity = ([1–12b])/([1–12b] + [1–12c]) × 100%. ND = not detected.

We found no obvious correlation between the substitution pattern of the aromatic substituent with the selectivity (halide vs aldehyde product).

As shown in Figure 2, the vinyl bromide selectivity was rather poor in some cases. Based on the mechanistic proposal (Scheme 2), we hypothesized that the water activity may play a decisive influence on the vinyl bromide/aldehyde selectivity. To test this, we performed a range of experiments increasing the cosolvent concentration (DMSO) from 5% (v/v) to 50% (v/v) (Figure 3). Indeed, this approach proved successful increasing of the selectivity for 10b and 11b from roughly 25 to 95% (see also Figures S38 and S39 for 10a and Figures S40 and S41 for 11b). Also, other cosolvents such as methanol, isopropanol, or acetone had similar effects. We therefore concluded that medium engineering represents an excellent handle to control the selectivity of the oxidative decarboxylation.

Figure 3.

Dependence of the selectivity on the solvent content. Conditions: [substrates] = 30 mM, citrate buffer (100 mM, pH 5), [CiVCPO]= 400 mM, [KBr] = 50 mM, [H2O2] = 30 mM, 30 °C, 6 h, 5 and 50% DMSO. A duplicate experiment was performed.

Finally, we explored the synthetic potential of the vinyl bromides obtained from the chemoenzymatic Hunsdieker reaction. For this, we submitted the products 3b and 12b to a photocatalytic [2 + 2] cycloaddition reaction with styrene,30 the Suzuki–Miyaura cross-coupling reaction with phenyl boronic acid,31 and a Pd-catalyzed Ullmann homocoupling reaction32 (Figure 4). In all cases, acceptable isolated yields of the desired products were obtained (for details, see the Supporting Information, Figures S43–S52).

Figure 4.

Expansion of chemoenzymatic Hunsdiecker-type reactions. Reaction conditions: (a) substrate = 0.22 mmol, styrene = 2.2 mmol, [TXT, (9-(2-methylphenyl)-1,3,6,8-tetramethoxythioxanthylium trifluoromethanesulfonate)] = 3 mol %, CH3CN, room-temperature (RT), air, green light-emitting diode (LED), 24 h; (b) [substrate] = 0.1–0.3 mmol, [phenyl boric acid] = 0.12–0.36 mol, [Pd(OAc)2] = 3 mol %, [orotic acid] = 6 mol %, [Cs2CO3] = 0.5 mmol, acetone, 100°C, N2, 16 h; and (c) [substrate] = 1 mmol, [Pd(OAc)2] = 0.02 mmol, Agarose = 0.05 g, [NaOH] = 1.5 mmol, H2O, 90°C, 12 h.

Conclusions

Overall, we have shown that vanadium chloroperoxidase from C. inaequalis is a robust catalyst for the oxidative decarboxylation of a broad scope of α,β-unsaturated carboxylic acids, establishing a chemoenzymatic Hunsdiecker reaction.

The selectivity of the reaction can be controlled by medium engineering, giving access to either the aldehyde or the vinyl bromide product.

The high activity and selectivity of the reaction and the mild and clean reaction conditions make the reaction attractive for the synthesis of valuable α,β-unsaturated halides from readily available starting materials.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 32171253 and 21776063), the European Union (Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No. 886567), and the Tianjin Synthetic Biotechnology Innovation Capacity Improvement Project (No. TSBICIP-CXRC-032). We thank Dr. Yonghong Yao and Dr. Yi Cai from TIB for their great assistance with GC–MS and NMR analysis.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acscatal.2c00485.

Experimental details, enzyme preparation, 1H and 13C NMR, GC–MS, and control experiments (PDF)

Author Contributions

H.L. and S.H.H.Y. have contributed equally. All the authors jointly wrote the article. All the authors have given their approval to the final version of the article.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Biffis A.; Centomo P.; Del Zotto A.; Zecca M. Pd Metal Catalysts for Cross-Couplings and Related Reactions in the 21st Century: A Critical Review. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 2249–2295. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki N.; Hofstra J. L.; Poremba K. E.; Reisman S. E. Nickel-Catalyzed Enantioselective Cross-Coupling of N-Hydroxyphthalimide Esters with Vinyl Bromides. Org. Lett. 2017, 19, 2150–2153. 10.1021/acs.orglett.7b00793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes S.; Huigens Iii R. W.; Su Z.; Simon M. L.; Melander C. Synthesis and biological activity of 2-aminoimidazole triazoles accessed by Suzuki–Miyaura cross-coupling. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2011, 9, 3041–3049. 10.1039/c0ob00925c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varenikov A.; Shapiro E.; Gandelman M. Decarboxylative Halogenation of Organic Compounds. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 412–484. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.0c00813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunsdiecker H.; Hunsdiecker C. Über den Abbau der Salze aliphatischer Säuren durch Brom. Ber. Dtsch. Chem. Ges. 1942, 75, 291–297. 10.1002/cber.19420750309. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cristol S. J.; Firth W. C. A Convenient synthesis of Alkyl Halides from Carboxylic acids. J. Org. Chem. 1961, 26, 280. 10.1021/jo01060a628. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kochi J. K. A New Method for Halodecarboxylation of Acids Using Lead(IV) Acetate. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1965, 87, 2500–2502. 10.1021/ja01089a041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barton D. H. R.; Faro H. P.; Serebryakov E. P.; Woolsey N. F. 445. Photochemical transformations. Part XVII. Improved methods for the decarboxylation of acids. J. Chem. Soc. 1965, 2438–2444. 10.1039/jr9650002438. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Concepcion J. I.; Francisco C. G.; Freire R.; Hernandez R.; Salazar J. A.; Suarez E. Iodosobenzene diacetate, an efficient reagent for the oxidative decarboxylation of carboxylic acids. J. Org. Chem. 1986, 51, 402–404. 10.1021/jo00353a026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury S.; Roy S. The First Example of a Catalytic Hunsdiecker Reaction: Synthesis of β-Halostyrenes. J. Org. Chem. 1997, 62, 199–200. 10.1021/jo951991f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazarika D.; Phukan P. TsNBr2 promoted decarboxylative bromination of α,β-unsaturated carboxylic acids. Tetrahedron Lett. 2018, 59, 4593–4596. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2018.11.041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Telvekar V. N.; Takale B. S. A novel method for bromodecarboxylation of α,β-unsaturated carboxylic acids using catalytic sodium nitrite. Tetrahedron Lett. 2011, 52, 2394–2396. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2011.02.101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hatvate N. T.; Takale B. S.; Ghodse S. M.; Telvekar V. N. Transition metal free large-scale synthesis of aromatic vinyl chlorides from aromatic vinyl carboxylic acids using bleach. Tetrahedron Lett. 2018, 59, 3892–3894. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2018.09.034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X.; Sun M.; Zhao Y.; Wang C.; Ma W.; Wong M. S.; Elimelech M. In Situ Electrochemical Generation of Reactive Chlorine Species for Efficient Ultrafiltration Membrane Self-Cleaning. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 6997–7007. 10.1021/acs.est.0c01590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bortolini O.; Carraro M.; Conte V.; Moro S. Vanadium-bromoperoxidase-mimicking systems: Direct evidence of a hypobromite-like vanadium intermediate. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2003, 2003, 42–46. 10.1002/ejic.200390004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Conte V.; Floris B.; Galloni P.; Silvagni A. Sustainable vanadium(V)-catalyzed oxybromination of styrene: Two-phase system versus ionic liquids. Pure Appl. Chem. 2005, 77, 1575–1581. 10.1351/pac200577091575. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Conte V.; Floris B. Vanadium catalyzed oxidation with hydrogen peroxide. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2010, 363, 1935–1946. 10.1016/j.ica.2009.06.056. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Galloni P.; Mancini M.; Floris B.; Conte V. Sustainable V-catalyzed Two-phase Procedure for Toluene Bromination with H2O2/KBr. Dalton Trans. 2013, 42, 11963–11970. 10.1039/c3dt50907a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha J.; Layek S.; Mandal G. C.; Bhattacharjee M. A Hunsdiecker reaction: synthesis of β-bromostyrenes from the reaction of α,β-unsaturated aromatic carboxylic acids with KBr and H2O2 catalysed by Na2MoO4·2H2O in aqueous medium. Chem. Commun. 2001, 1916–1917. 10.1039/b104540g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada H.; Itoh N.; Izumi Y. Chloroperoxidase-catalyzed Halogenation of trans-Cinnamic acid and its derivatives. J. Biol. Chem. 1985, 260, 1962–1969. 10.1016/S0021-9258(17)38971-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobisch M.; Holtmann D.; de Santos P. G.; Alcalde M.; Hollmann F.; Kara S. Recent developments in the use of peroxygenases—Exploring their high potential in selective oxyfunctionalisations. Biotechnol. Adv. 2021, 51, 107615 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2020.107615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Rantwijk F.; Sheldon R. A. Selective oxygen transfer catalysed by heme peroxidases: synthetic and mechanistic aspects. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2000, 11, 554–564. 10.1016/S0958-1669(00)00143-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X. M.; But A.; Wever R.; Hollmann F. Towards Preparative Chemoenzymatic Oxidative Decarboxylation of Glutamic Acid. ChemCatChem 2020, 12, 2180–2183. 10.1002/cctc.201902194. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- But A.; Le Nôtre J.; Scott E. L.; Wever R.; Sanders J. P. M. Selective Oxidative Decarboxylation of Amino Acids to Produce Industrially Relevant Nitriles by Vanadium Chloroperoxidase. ChemSusChem 2012, 5, 1199–1202. 10.1002/cssc.201200098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasan Z.; Renirie R.; Kerkman R.; Ruijssenaars H. J.; Hartog A. F.; Wever R. Laboratory-evolved vanadium chloroperoxidase exhibits 100-fold higher halogenating activity at alkaline pH—Catalytic effects from first and second coordination sphere mutations. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 9738–9744. 10.1074/jbc.M512166200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Schijndel J. W. P. M.; Vollenbroek E. G. M.; Wever R. The chloroperoxidase from the fungus Curvularia inaequalis—a novel vanadium enzyme. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Protein Struct. Mol. Enzymol. 1993, 1161, 249–256. 10.1016/0167-4838(93)90221-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renirie R.; Pierlot C.; Aubry J.-M.; Hartog A. F.; Schoemaker H. E.; Alsters P. L.; Wever R. Vanadium Chloroperoxidase as a Catalyst for Hydrogen Peroxide Disproportionation to Singlet Oxygen in Mildly Acidic Aqueous Environment. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2003, 345, 849–858. 10.1002/adsc.200303008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Fueyo E.; Younes S. H. H.; Rootselaar S.; Aben R. W. M.; Renirie R.; Wever R.; Holtmann D.; Rutjes F. P. J. T.; Hollmann F. A biocatalytic Aza-Achmatowicz reaction. ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 5904–5907. 10.1021/acscatal.6b01636. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Fueyo E.; van Wingerden M.; Renirie R.; Wever R.; Ni Y.; Holtmann D.; Hollmann F. Chemoenzymatic halogenation of phenols by using the haloperoxidase from Curvularia inaequalis. ChemCatChem 2015, 7, 4035–4038. 10.1002/cctc.201500862. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka K.; Iwama Y.; Kishimoto M.; Ohtsuka N.; Hoshino Y.; Honda K. Redox Potential Controlled Selective Oxidation of Styrenes for Regio- and Stereoselective Crossed Intermolecular [2 + 2] Cycloaddition via Organophotoredox Catalysis. Org. Lett. 2020, 22, 5207–5211. 10.1021/acs.orglett.0c01852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H.-P.; Dai Y.-Z.; Zhou X.; Yu H. Efficient Pyrimidone-Promoted Palladium-Catalyzed Suzuki–Miyaura Cross-Coupling Reaction. Synlett 2012, 23, 1221–1224. 10.1055/s-0031-1290885. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Firouzabadi H.; Iranpoor N.; Kazemi F. Carbon–carbon bond formation via homocoupling reaction of substrates with a broad diversity in water using Pd(OAc)2 and agarose hydrogel as a bioorganic ligand, support and reductant. J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem. 2011, 348, 94–99. 10.1016/j.molcata.2011.08.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.