Abstract

Oxalic acid is an important separation agent in the technology of lanthanides, actinides, and transition metals. Thanks to the low solubility of the oxalate salts, the metal ions can be easily precipitated into crystalline material, which is a convenient precursor for oxide preparation. However, it is difficult to obtain oxalate monocrystals due to the fast precipitation. We have developed a synthetic route for homogeneous precipitation of oxalates based on the thermal decomposition of oxamic acid. This work primarily concerns lanthanide oxalates; however, since no information was found about oxamic acid, a brief characterization was included. The precipitation method was tested on selected elements (Ce, Pr, Gd, Er, and Yb), for which the kinetics was determined at 100 °C. Several scoping tests at 90 °C or using different starting concentrations were performed on Ce and Gd. The reaction products were studied by means of solid-state analysis with focus on the structure and morphology. Well-developed microcrystals were successfully synthesized with the largest size for gadolinium oxalate.

Introduction

Precipitation reactions can be divided into two categories: heterogeneous and homogeneous. Heterogeneous precipitation is performed by the addition of the precipitating agent directly to the solution of metal ions. This creates a supersaturation in the solution and results in a rapid formation of many crystallization nuclei. Homogeneous precipitation, on the other hand, is performed by slowly generating the precipitating agent by chemical decomposition of a precursor. The supersaturation of the solution in this case is low, and the crystallites grow at much slower rate, resulting in different crystallization conditions than during the heterogeneous precipitation.

One of the most widely used precipitating agents is oxalic acid, which forms insoluble precipitates with most of transition metal ions, lanthanides, and actinides.1,2 Indeed, actinide oxalates have proven useful in lanthanide/actinide separation from their solutions.1,3,4 Oxalates are simply low-cost but high-quality precursors for materials with interesting properties, such as nuclear fuels,5−8 metal–organic frameworks,9,10 oxygen conductors,11 or molecular magnets.12

In the present work, we aimed on the development of a homogeneous precipitation of oxalates to achieve slower kinetics of precipitation and therefore larger crystals than usually obtained. There are only few attempts described in the literature. Rao et al.13 reported synthesis of Pu(C2O4)2·6H2O by decomposition (hydrolysis) of diethyl oxalate in presence of plutonium nitrate at various temperatures (25–77 °C). This technique was later exploited in the works of Pazukhin et al.14 and Tamain et al.,15 both dedicated to actinides. Even if the technique gave well-developed crystals, its main disadvantage is use of concentrated acid solutions and organic solvents (alcohol). We have unsuccessfully tested various basic carboxylic acids or derivates of oxalic acid (e.g., glyoxylic acid), until effective results were obtained using oxamic acid.

Oxamic acid (also known as 2-amino-2-oxoethanoic acid or 2-amino-2-oxoacetic acid) is the simplest known dicarboxylic acid containing an amide group. It is a very polar molecule, mostly available in a form of white fine powder, which is insoluble in organic solvents.16 It melts, while decomposing, at 209 °C.17 Apart from its biochemical activity,17−19 the basic physicochemical properties have not been reported. The structure of crystalline oxamic acid (space group no. 9, Cc) was reported recently showing the importance of the H-bonds.20 Likewise, the coordination chemistry of oxamic acid received limited attention. It is mostly focused on the coordination modes (through carboxylate or amide groups) and spectroscopic data; for examples of transition metal’s complexes, see refs (21)–24; for lanthanide’s complexes, see refs (25)–28.

In the present article, we describe the homogenous precipitation of lanthanide oxalates by oxamic acid decomposition. We have selected lanthanide’s representatives (Ce, Pr, Gd, Er, and Yb) for clarity. Oxalates of the lighter lanthanides are somehow described as the P21/c structure of Ln2(C2O4)3·10H2O, while isomorphism is foreseen toward heavier lanthanides.29 However, the amount and bonding of water molecules may vary.1,29,30

Experimental Part

For the experiment, we used Ce(NO3)3·6H2O (Acros Organics, 99.5%), Pr(NO3)3·6H2O (Sigma-Aldrich, 99.9%), Gd(NO3)3·6H2O (Alfa Aesar, 99.9%), Er(NO3)3·6H2O (Sigma-Aldrich, 99.9%), Yb(NO3)3·6H2O (Sigma-Aldrich, 99.9%), and oxamic acid (Acros Organics, 98%). A series of experiments was performed to investigate the behavior of various lanthanides ions with oxamic acid. In a 50 mL round bottom flask, 25 mL of 0.2 M clear solution (5 mmol) of oxamic acid was heated to 40 °C to increase the dissolution of oxamic acid and was mixed with 10 mL of 0.2 M solution (2 mmol) of Ln(NO3). Ce, Pr, Gd, Er, and Yb were chosen as representants of lighter and heavier lanthanides. When mixing the solutions, no precipitate was formed, and clear solution was obtained. The solution was mixed with a magnetic stirrer at 500 rpm. The solution was heated to 100 °C and kept at this temperature for 2 h. In order to prevent the solvent from evaporating, a glass air condenser was attached to the flask. After the reaction was finished, the obtained precipitate was washed twice with distilled water and centrifugated for 5 min at 5000 rpm. The precipitate was dried overnight in an oven at 40 °C.

Kinetic Studies

We investigated the reaction kinetics of the precipitate formation during the experiment. Every 30 min, 5 mL of solution was transferred into a test tube and centrifugated for 2 min at 5000 rpm. We took 4 mL of this solution and added 1.2 mmol H2C2O4·2H2O for quantitative separation of unreacted lanthanides. The concentration of Ln3+ ions in the solution was calculated from the mass of the precipitate. The kinetic studies were performed for Ce, Pr, and Gd samples.

Optical micrographs were received on Leica DM4000 m equipped with a Leica DFC295 camera. The morphology of the precipitates was observed using scanning electron microscopes JEOL JSM-6510. The samples were coated with a thin Au/Pd conductive layer. Powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) was measured on a PANalytical X’Pert PRO diffractometer (Cu Kα radiation) calibrated on a LaB6 (NIST) standard. The pattern was treated using JANA2006 software. The UV–vis absorption spectra were obtained on a Unicam 340 spectrometer or on a Varian 4000 spectrometer equipped with an integration sphere. Thermogravimetric analysis was performed on a SETYS Evolution thermogravimeter from SETARAM. The sample was heated from room temperature, with a 20 min delay at 40 °C for drying, with a slope of 3 K/min to 800 °C in a 100 μL alumina crucible.

Results and Discussion

Oxamic Acid and Its Affinity to Lanthanides

Because very limited information is known about oxamic acid, we performed a set of basic characterization to facilitate the manipulation and further reactions with it. The solubility at 25 °C was estimated to be 8.50 ± 0.06 g per 100 g of water. We have found that water solutions heated over 40 °C are unstable and slowly lead to decomposition (see Figure S1 in the Supporting Information). The pKA of oxamic acid was determined to be 3.18 (see Figure S2 in the Supporting Information). Heating the oxamic acid in solution causes it to decompose into ammonium oxalate; for the mechanism, see Figure 1. Whole dedicated work can be found in the thesis of Zakharanka.30

Figure 1.

Mechanism of oxamic acid hydrolysis, in principle, known as acid-catalyzed hydrolysis of amides.

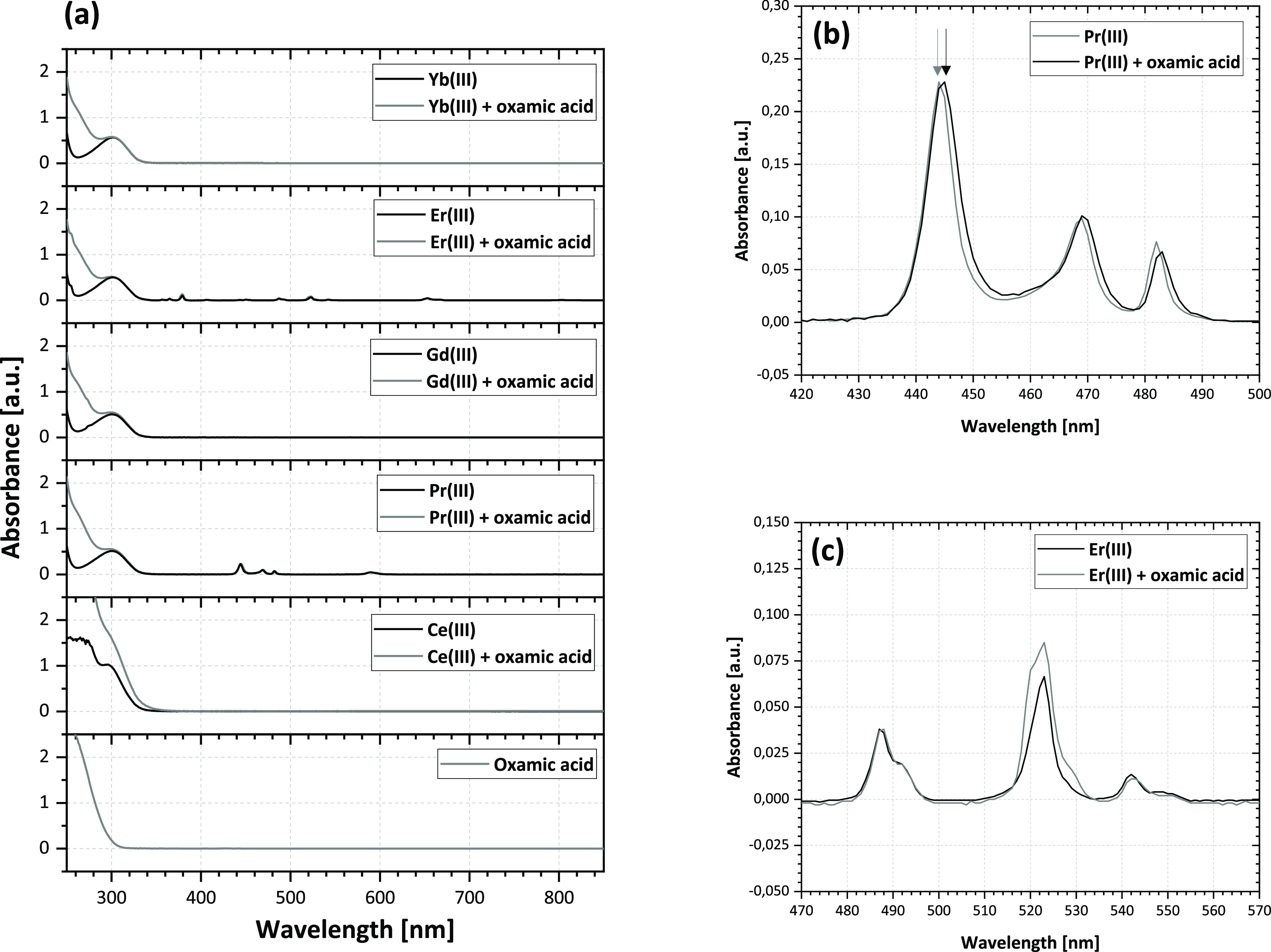

This reaction basically makes oxalic acid free for reaction with lanthanide ions to form an insoluble salt. When mixing the oxamic acid solution and lanthanide salt, no precipitate was formed; moreover, no observable interaction was found using UV/vis spectroscopy. Figure 2 shows the UV/Vis spectra of pure oxamic–lanthanide nitrate solutions and their corresponding mixtures.

Figure 2.

UV/vis spectra of oxamic acid [bottom graph, (a)]. Lanthanide nitrate solutions and their equimolar mixtures (a) and detailed views of Pr(III) and Er(III) spectra in a mixture with oxamic acid (b,c).

Very limited change in the absorption peak positions or intensity was observed during the interaction of oxamic acid and selected lanthanide ions in solution. The spectra of the mixtures are basically a sum of the oxamic acid and lanthanides. A slight shift (∼2 nm) was found between the spectrum of Er(III) solution before and after oxamic acid addition (Figure 2c). A similar shift (∼5 nm) was also found for the uranyl ion and urea (containing the −NH2 group as well);31 however, it was not as strong in our case. Moreover, this shift was not observed in the case of Er(III) (Figure 2c). Therefore, we assume that oxamic acid coordination had limited impact on the electronic structure of the ions; however, a deeper coordination study would be necessary to confirm and describe the behavior.

Kinetics of Oxalate Precipitation

We have performed the homogenous precipitation of oxalate salts on selected lanthanides (Ce, Pr, Gd, Er, and Yb) to have a general impression. The Ln2(C2O4)3·nH2O precipitation kinetics at 100 °C is plotted in Figure 3 as a residual concentration of Ln(III) ions in the solution. The time of complete precipitation at 100 °C is in the range of hours, which is convenient for the laboratory practice. The first-order kinetics fits well the oxalate precipitation. It was found that the heavier the lanthanide, the slower is the precipitation at the same temperature. The kinetic constants (k in min–1) at 100 °C decrease with the atomic number of the lanthanide as follows: k = −0.0002x + 0.0181 (Rsq = 0.784), where x is the atomic number of the lanthanide.

Figure 3.

Kinetics of homogeneous oxalate precipitation expressed by the residual contractions of lanthanide ions in the solution. Tests were performed at 100 °C. The data were fitted by exponential fit c = a·e–kt, where c stands for the concentration in mmol/L, a is a pre-exponential factor, k is the kinetic constant, and t is time. R-square factors and the 95% confidence bands are presented (in red).

The precipitation could be slowed down more by decreasing the temperature. Figure 4 shows the Ce(III) precipitation kinetics (in a similar way as Figure 3) for 90 and 100 °C. The first-order kinetic constants are k(100 °C) = 0.0214 min–1 (Rsq = 0.983) and k(90 °C) = 0.01 min–1 (Rsq = 0.959). Thus, the precipitation is about 2.15 times slower at 90 °C compared to 100 °C.

Figure 4.

Kinetics of oxalate precipitation for Ce(III) at 90 and 100 °C with the exponential fits and 95% confidence bands (in red); c = 0.057e–0.010t for 90 C (Rsq = 0.96) and c = 0.58e–0.021t for 100 C (Rsq = 0.98).

Morphology of the Precipitates

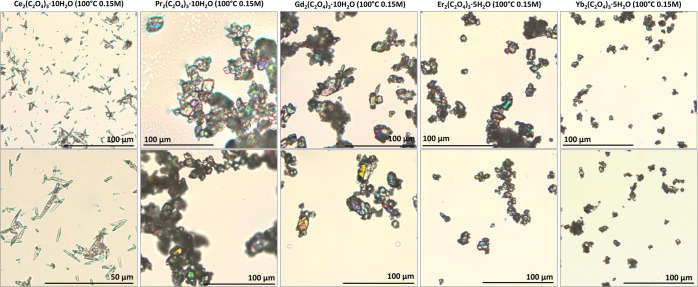

The morphology and composition of the precipitates were studied using various techniques of solid-state analysis. Figure 5 shows the optical microscopy of the precipitates obtained at 100 °C with a starting concentration of Ce(III) 0.15 mol/L. The morphology was dependent on the lanthanide used; Ce(III) formed mostly needles, while other lanthanides formed regular crystals, occasionally prolonged. Interestingly, the size of the crystals was also linked with the lanthanide. Having equal precipitation conditions, we found the largest crystals for gadolinium, while the smallest for the heaviest ytterbium. The cerium(III) oxalate was up to 50 μm long and 20 μm wide. The other lanthanide oxalates having a similar morphology were up 50 μm in diameter for gadolinium, otherwise considerably smaller.

Figure 5.

Optical micrographs of oxalate precipitates obtained at 100 °C and a 0.15 M starting concentration.

Apart from the temperature, other possible modification of the synthetic path was to reduce substantially the concentration. We performed such a study on Ce(III); the initial concentration of Ce(III) was decreased from 0.06 to 0.01 M, maintaining the other conditions equal. A lower concentration of metal led to smaller shape anisotropy of the crystals and better homogeneity of the size (see Figure 6). To see the capabilities of the technique to produce lanthanide–oxalate single crystals, we performed an additional test. As Gd(III) gave the largest crystals, we increased the concentration to 0.5 M and decreased temperature to 90 °C. The size of the crystals is smaller than reported for the diethyl oxalate decomposition method;15 however, it meets the requirement for single crystal X-ray diffraction and requires a considerably simpler synthetic approach Figure 7. A larger parametrical study would be necessary to further asses the shape and size of the crystals depending on various conditions; however, such a study would be beyond the scope of the present work.

Figure 6.

Cerium(III) oxalate crystals obtained at 100 °C. Smaller particles having lower shape anisotropy were obtained from diluted solutions, c(Ce) = 0.01 M (a), while larger crystals were precipitated from more concentrated solution, c(Ce) = 0.06 M (b).

Figure 7.

Optical micrographs of Gd(III) oxalate formed at 90 °C using 0.5 M starting solution.

Composition and Structure of the Oxalates

The structure of the precipitates was examined by X-ray powder diffraction. In the case of lighter lanthanides (Ce, Pr, and Gd), the composition and structure were easily determined (see Figure 8). All three oxalates belong to the typical Ln2(C2O4)3·10H2O composition with the P21/c structure.29 The lattice parameters a, b, and c decreased with the ionic radius of heavier lanthanides (Figure 8d or see Table S1). The amounts of water molecules in the structures were confirmed using thermogravimetric measurements (Figure 9). The situation concerning the heavier oxalates of Er(III) and (Yb) was rather complicated. None of the ICSD32 data record fit exactly our measurements, (see Figures S3 and S4 in the Supporting Information). Indeed, the erbium oxalate was reported as a hexahydrate33 or trihydrate,34 similar as ytterbium being a penta or hexahydrate.35 These uncertainties in the crystalline water content played an important role in precluding the structure determination in our case. Figure 9 shows that the dehydration of cerium oxalate is a one-step process, but from gadolinium oxalate toward heavier lanthanides, the dehydration was a multistep process. Moreover, based on the thermogravimetry measurements, we observed the Er(III) and Yb(III) oxalates as pentahydrates. It seems that the water molecules, which are not participating in the coordination polyhedra, are loosely bound in the lattice for heavier lanthanides (Er and Yb), and therefore, the total number of water molecules per unit might fluctuate easily.

Figure 8.

X-ray powder diffraction of the Ce(III) (a), Pr(III) (b), and Gd(III) (c) oxlate decahydrate having a typical C/2m structure. Imeas stands for measure intensity, Icalc for calculated, and Idiff for the difference curve (Icalc – Imeas). The lattice parameter for all three Ln(III) oxalate decahydrates is given in (d); fitting parameters are as follows: Ce(III) oxalate Rwp = 7.03, GOF = 1.79; Pr(III) oxalate Rwp = 7.26, GOF = 1.81; and Gd(III) oxalate Rwp = 7.46, GOF = 2.11.

Figure 9.

Decomposition of hydrated lanthanide oxalates Ln3(C2O4)3·nH2O by thermogravimetric measurements under air.

This fact also corresponds to the electron microscopy observations, which were performed in vacuum. The cerium oxalate decahydrate remained intact during the SEM observation (see Figure 6), but one can see cracks on the surface of both erbium and ytterbium oxalates (Figures S5 and S6 in the Supporting Information), implying the dehydration of the crystals only under vacuum. Unfortunately, precise structure determination of Er(III) and Yb(III) oxalates would be beyond the scope of the present work. However, we believe that the synthetic route described in this article will help to unravel the question about the structure of oxalates in the future.

Conclusions

In the present work, we focused on the development of homogeneous precipitation of lanthanide oxalates Ln2(C2O4)3·nH2O. Homogeneous precipitation has the advantage of equal distribution of the precipitation agent throughout the reactant mixture and slower precipitation caused by the in situ generation of the precipitation agent. We have developed a laboratory-convenient way of homogeneous precipitation of oxalates by thermal decomposition of oxamic acid. The precipitation was described for selected lanthanides by means of pseudo first-order kinetics. It was found that the precipitation was naturally slower for heavier lanthanides and lower temperatures. Interestingly, the precipitates showed maximum size for Gd2(C2O4)3·10H2O and minimum for heavy lanthanides [Yb2(C2O4)3·7H2O]. Cerium oxalate had a significantly different morphology than the others, and it formed mainly needles instead of compact microcrystals. It was proved that by slowing down the precipitation (from 100 to 90 °C) and increasing the starting concentration, the crystal grew even more (up to ∼80 μm). Our work showed the gaps in the structure determination and behavior of heavy lanthanide oxalates, which is most probably linked with the loosely bound crystalline water.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the Czech Science Foundation (GAČR), under project 20-20936Y “Microstructural and chemical effects during flash sintering of refractory oxides”.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.2c00763.

X-ray powder diffraction of the oxamic acid decomposition product, erbium oxalate, and ytterbium oxalate; titration curve of oxamic acid; and SEM micrographs of erbium and ytterbium oxalates (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Abraham F.; Arab-Chapelet B.; Rivenet M.; Tamain C.; Grandjean S. Actinide Oxalates, Solid State Structures and Applications. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2014, 266–267, 28–68. 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.08.036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rao C. N. R.; Natarajan S.; Vaidhyanathan R. Metal carboxylates with open architectures. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2004, 43, 1466–1496. 10.1002/anie.200300588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinin D. S.; Bushuev N. N. Separate Crystallization of Lanthanide Oxalates and Calcium Oxalates from Nitric Acid Solutions. Russ. J. Inorg. Chem. 2018, 63, 1211–1216. 10.1134/S003602361809022X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ellart M.; Blanchard F.; Rivenet M.; Abraham F. Structural Variations of 2D and 3D Lanthanide Oxalate Frameworks Hydrothermally Synthesized in the Presence of Hydrazinium Ions. Inorg. Chem. 2020, 59, 491–504. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.9b02781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arab-Chapelet B.; Grandjean S.; Nowogrocki G.; Abraham F. Synthesis of new mixed actinides oxalates as precursors of actinides oxide solid solutions. J. Alloys Compd. 2007, 444–445, 387–390. 10.1016/j.jallcom.2007.01.033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tyrpekl V.; Beliš M.; Wangle T.; Vleugels J.; Verwerft M. Alterations of thorium oxalate morphology by changing elementary precipitation conditions. J. Nucl. Mater. 2017, 493, 255–263. 10.1016/j.jnucmat.2017.06.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Modolo G.; Vijgen H.; Serrano-Purroy D.; Christiansen B.; Malmbeck R.; Sorel C.; Baron P. DIAMEX Counter-Current Extraction Process for Recovery of Trivalent Actinides from Simulated High Active Concentrate. Sep. Sci. Technol. 2007, 42, 439–452. 10.1080/01496390601120763. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tyrpekl V.; Vigier J.-F.; Manara D.; Wiss T.; Dieste Blanco O.; Somers J. Low temperature decomposition of U(IV) and Th(IV) oxalates to nanograined oxide powders. J. Nucl. Mater. 2015, 460, 200–208. 10.1016/j.jnucmat.2015.02.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H.-C.; Long J. R.; Yaghi O. M. Introduction to Metal–Organic Frameworks. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 673–674. 10.1021/cr300014x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu W.-H.; Wang Z.-M.; Gao S. Two 3D porous lanthanide-fumarate-oxalate frameworks exhibiting framework dynamics and luminescent change upon reversible de- and rehydration. Inorg. Chem. 2007, 46, 1337–1342. 10.1021/ic061833e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyrpekl V.; Markova P.; Dopita M.; Brázda P.; Vacca M. A. Cerium Oxalate Morphotypes: Synthesis and Conversion into Nanocrystalline Oxide. Inorg. Chem. 2019, 58, 10111–10118. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.9b01250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu G.-F.; Wang Q.-L.; Gamez P.; Ma Y.; Clérac R.; Tang J.; Yan S.-P.; Cheng P.; Liao D.-Z. A promising new route towards single-molecule magnets based on the oxalate ligand. Chem. Commun. 2010, 46, 1506–1508. 10.1039/B920215C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao V. K.; Pius I. C.; Subbarao M.; Chinnusamy A.; Natarajan P. R. Precipitation of plutonium oxalate from homogeneous solutions. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 1986, 100, 129–134. 10.1007/BF02036506. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pazukhin E. M.; Galkin B. Ya.; Krinitsyn A. P.; Pokhitonov Yu. A.; Ryazantsev V. I. Separation of Am(III) and Pu(IV) at their joint oxalate precipitation. Radiochemistry 2003, 45, 159–166. 10.1023/A:1023885310014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tamain C.; Arab-Chapelet B.; Rivenet M.; Grandjean S.; Abraham F. Crystal growth methods dedicated to low solubility actinide oxalates. J. Solid State Chem. 2016, 236, 246–256. 10.1016/j.jssc.2015.07.045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raczyńska E. D.; Hallmann M.; Duczmal K. Quantum-chemical studies of amide-iminol tautomerism for inhibitor of lactate dehydrogenase: Oxamic acid. Comput. Theor. Chem. 2011, 964, 310–317. 10.1016/j.comptc.2011.01.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi G. N. R.; Katon J. E. Vibrational Spectra and Structure of Crystalline Oxamic Acid and Sodium Oxamate. Spectrochim. Acta, Part A 1979, 35, 401–407. 10.1016/0584-8539(79)80152-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berg J. M.; Tzmoczko J. L.; Stryer L.; Gatto G. J.. Biochemistry, 7th ed.; W.H.Freeman: New York, NY, 1975; Vol. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- O’Carra P.; Barry S. Lactate Dehydrogenase: Specific Ligand Approach. Methods Enzymol. 1974, 34, 598–605. 10.1016/S0076-6879(74)34080-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dugarte-Dugarte A. J.; van de Streek J.; dos Santos A. M.; Daemen L. L.; Puretzky A. A.; Díaz de Delgado G.; Delgado J. M. Structure Determination of Oxamic Acid from Laboratory Powder X-Ray Diffraction Data and Energy Minimization by DFT-D. J. Mol. Struct. 2019, 1177, 310–316. 10.1016/j.molstruc.2018.09.089. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schoeters G.; Deleersnijder D.; Desseyn H. O. The complexes of oxamic acid with Ni(II). Spectrochim. Acta, Part A 1983, 39, 71–76. 10.1016/0584-8539(83)80058-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vansant C.; Desseyn H. O.; Perlepes S. P. The Synthesis, Spectroscopic and Thermal Study of Oxamic Acid Compounds of Some Metal(II) Ions. Transition Met. Chem. 1995, 20, 454–459. 10.1007/BF00141516. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kouinis J. K.; Velsistas P. T.; Tsangaris J. M. Complexes of Oxamic Acid with Au(III) and Rh(III). Monatsh. Chem. 1982, 113, 155–161. 10.1007/BF00799014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Michaelides A.; Skoulika S. Gel Growth of Single Crystals of Complexes of Oxamic Acid with Divalent Metals (Pb2+, Ca2+, Cd2+). J. Cryst. Growth 1989, 94, 208–212. 10.1016/0022-0248(89)90620-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Caires F. J.; Lima L. S.; Gomes D. J. C.; Gigante A. C.; Treu-Filho O.; Ionashiro M. Thermal and Spectroscopic Studies of Solid Oxamate of Light Trivalent Lanthanides. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2013, 111, 349–355. 10.1007/s10973-012-2220-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lazaridou V.; Perlepes S. P.; Tsangaris J. M.; Zafiropoulos T. F. Synthesis, Physical Properties and Spectroscopic Studies of Oxamato (−1) Lanthanide(III) Complexes. J. Less-Common Met. 1990, 158, 1–14. 10.1016/0022-5088(90)90425-J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Caires F. J.; Nunes W. D. G.; Gaglieri C.; Nascimento A. L. C. S. d.; Teixeira J. A.; Zangaro G. A. C.; Treu-Filho O.; Ionashiro M. Thermoanalytical, Spectroscopic and DFT Studies of Heavy Trivalent Lanthanides and Yttrium(III) with Oxamate as Ligand. Mater. Res. 2017, 20, 937–944. 10.1590/1980-5373-mr-2016-0633. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Perlepes S. P.; Zafiropoulos T. F.; Kouinis J. K.; Galinos A. G. Lanthanide(III) Complexes of Oxamic Acid. Z. Naturforsch., B: Anorg. Chem., Org. Chem. 1981, 36, 697–703. 10.1515/znb-1981-0609. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ollendorff W.; Weigel F. The Crystal Structure of Some Lanthanide Oxalate Decahydrates, Ln2(C2O4)3·10H2O, with Ln = La, Ce, Pr, and Nd. Inorg. Nucl. Chem. Lett. 1969, 5, 263–269. 10.1016/0020-1650(69)80196-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zakharanka A.Physicochemical properties of oxamic and glyoxylic acids and their affinity to lanthanides. bachelor thesis, Charles University, 2021, https://dspace.cuni.cz/handle/20.500.11956/128205?locale-attribute=en. [Google Scholar]

- Schreinemachers C.; Bollen O.; Leinders G.; Tyrpekl V.; Modolo G.; Verwerft M.; Binnemans K.; Cardinaels T. Hydrolysis of uranyl-, Nd-, Ce-ions and their mixtures by thermal decomposition of urea. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2022, 2022, 1–5. 10.1002/ejic.202100453. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- ICSD . Inorganic Crystal Structure Database. http://www2.fiz-karlsruhe.de/icsd_home.html, January, 2022.

- Steinfink H.; Brunton G. D. The Crystal Structure of Erbium Oxalate Trihydrate. Inorg. Chem. 1970, 9, 2112–2115. 10.1021/ic50091a030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Balboul B. A. A. Thermal decomposition study of erbium oxalate hexahydrate. Thermochim. Acta 2000, 351, 55–60. 10.1016/S0040-6031(00)00353-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Glasner A.; Levy E.; Steinberg M. Thermal decomposition of ytterbium oxalate. J. Inorg. Nucl. Chem. 1964, 26, 1143–1149. 10.1016/0022-1902(64)80191-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.