Abstract

Purpose:

Radiation-induced lung injury is a major dose-limiting toxicity for thoracic radiotherapy patients. In experimental models, treatment with angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors mitigates radiation pneumonitis; however, the mechanism of action is not well understood. Here, we evaluate the direct role of ACE inhibition on lung immune cells.

Methods and Materials:

ACE expression and activity were determined in the lung immune cell compartment of irradiated adult rats following either high dose fractionated radiation therapy (RT) to the right lung (5 fractions × 9 Gy) or a single dose of 13.5 Gy partial body irradiation (PBI). Mitigation of radiation-induced pneumonitis with the ACE-inhibitor lisinopril was evaluated in the 13.5 Gy rat PBI model. During pneumonitis, we characterized inflammation and immune cell content in the lungs and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF). In vitro mechanistic studies were performed using primary human monocytes and the human monocytic THP-1 cell line.

Results:

In both the PBI and fractionated RT models, radiation increased ACE activity in lung immune cells. Treatment with lisinopril improved survival during radiation pneumonitis (p=0.0004). Lisinopril abrogated radiation-induced increases in BALF MCP-1 (CCL2) and MIP-1α cytokine levels (p < 0.0001). Treatment with lisinopril reduced both ACE expression (p=0.006) and frequency of CD45+CD11b+ lung myeloid cells (p=0.004). In vitro, radiation injury acutely increased ACE activity (p=0.045) and reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation (p=0.004) in human monocytes, whereas treatment with lisinopril blocked radiation-induced increases in both ACE and ROS. Interestingly, radiation-induced ROS generation was blocked by pharmacological inhibition of either NADPH oxidase 2 (NOX2) (p=0.012) or the type 1 angiotensin receptor (AGTR1) (p=0.013).

Conclusions:

These data demonstrate radiation-induced ACE activation within the immune compartment promotes the pathogenesis of radiation pneumonitis, while ACE inhibition suppresses activation of pro-inflammatory immune cell subsets. Mechanistically, our in vitro data demonstrate radiation directly activates the ACE/AGTR1 pathway in immune cells and promotes generation of ROS via Nox2.

Keywords: Radiation Pneumonitis, Radiation-Induced Lung Injury, Angiotensin Converting Enzyme, ACE inhibitors, NAD(P)H oxidase 2

Introduction

Radiation-induced lung injury (RILI) is a concern for both cancer patients undergoing thoracic radiotherapy and victims of accidental radiation exposure. For cancer patients, RILI is a dose-limiting factor in radiotherapy for thoracic cancers and occurs in roughly 5–25% of lung cancer patients despite constrained treatment doses (1). Historically, in victims of accidental radiation exposure or nuclear warfare, more than 50% of victims experience pulmonary toxicity (2). RILI manifests first as pneumonitis characterized by high oxidative stress, vascular damage, and inflammation (3). Both pulmonary pneumonitis and fibrosis impair lung function, reduce patient quality of life, and can cause death due to respiratory failure (4). For these reasons, it is critical to understand the mechanisms which promote the pathogenesis of RILI to enable the development of targeted therapeutics.

Over the past two decades, angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors have been demonstrated to be effective mitigators of radiation injury to multiple organ systems including: acute hematopoietic injury (5), pneumonitis (2,6,7), cardiac fibrosis (8), optic neuropathy (9,10), and nephropathy (11,12). Clinically, the incidental use of ACE inhibitors has also been associated with a decrease in radiation-induced pneumonitis in lung cancer patients (13). Although genetic and pharmacologic inhibition of ACE is known to improve late injury to multiple organ systems (2,6,8,12), the mechanisms of these actions are unclear. ACE inhibitor treatment has well-established function as a vasodilator and a suppressor of reactive oxygen species production in the vasculature; however, ACE activity falls in the lung perfusate during radiation pneumonitis due to pulmonary vasculature regression (14). These data would suggest ACE inhibitors may have a non-vascular cellular target in the mitigation of radiation pneumonitis. While ACE activity within the hematopoietic system is known to regulate hematopoietic differentiation and immune cell function (15–19), the role of ACE signaling in the immune compartment following radiation injury is largely unknown.

Here, we demonstrate for this first time that high dose irradiation to the lung increases ACE activity and downstream activation of the type 1 angiotensin receptor (AGTR1) within the lung immune cell compartment. Furthermore, we show pharmacologic inhibition with the ACE inhibitor lisinopril significantly improves survival during radiation pneumonitis in part by reducing ACE activation in immune cell subsets. Mechanistically, we observed ACE pathway activation in irradiated immune cells promotes ROS generation via activation of the type 1 angiotensin receptor (AGTR1) and downstream activation of NOX2. Additionally, secretion of monocyte chemotactic protein 1 (MCP-1/CCL2) is elevated by activation of the ACE signaling pathway and promotes immune cell adhesion to vascular endothelial cells.

Methods and Materials

Animals

All studies described were performed in accordance with an approved Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee protocol. WAG/RijCmcr rats were bred and maintained in a barrier facility at our institution. Two weeks prior to irradiation, rats were switched to a moderate antioxidant diet (Teklad Global 2018 diet) which is more representative of antioxidant levels in a human diet (20).

Fractionated Radiation Therapy (RT) Model

Fractionated radiation confined to a single lung was performed using the CT-guided SmART irradiator (Precision X-Ray, Madison, CT). Rats (n=4) were anesthetized by 3% isoflurane/room temperature air inhalation for the duration of each treatment. Pilot V1.8 Imaging Software (University Health Network, Toronto, Canada) was used to create two-dimensional projections over 360° to provide CT scans in transverse, sagittal, and frontal views. A circular 15 mm treatment field was centered on the right lung. Five fractions of 9 Gy were given once daily, with 2 equally weighted opposed parallel beams (225 kVp, 20 mA, 0.32 mm Cu filter (0.89 HVL), 4.26 Gy/min, beam angles 30 and 210 degrees). Control rats (n=4) received sham irradiation. Monte-Carlo-based treatment planning (MAASTRO Radiotherapy Clinic) was used to contour the heart, right, and left lungs.

Partial Body Irradiation (PBI) Model

Adult female WAG/RijCmcr rats (11–12 weeks old) were exposed to 13.5 Gy partial body irradiation (PBI) with bone marrow shielding to one hind-limb (X-RAD 320 Precision, 320 kVp; 173 cGy/min) as previously described (20,21). The PBI dose for female rats in this strain were based on the established LD50/120 radiation doses for male and female lung toxicity in this strain (20). All rats received supportive care post radiation consisting of antibiotics (enrofloxin ~10 mg/kg/day) in the drinking water from days 2–14, subcutaneous saline (40 ml/kg) days 2–10, and powdered diet days 35–70 (20). Lisinopril treatment (24 mg/m2/day or approximately 4 mg/kg/day) was administered in the drinking water starting at day 2 and continued until study endpoint. Survival Analysis: Morbidity due to radiation pneumonitis was characterized in a total of 30 animals (17 control and 13 lisinopril treated) through day 120 post-irradiation. Two independent cohorts of 12 female rats (6 control and 6 lisinopril treated) were established for scheduled euthanasia at day 70 for assessment of immune cell fractions and ACE activity as described below. As a complementary analysis, a single cohort of 8 adult male WAG/RijCmcr rats (4 control and 4 lisinopril treated) was analyzed at day 70 following the LD50/120, 13 Gy PBI.

Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) collection

Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) collection was performed as previously described (22,23). Briefly, rats were euthanized by isoflurane inhalation. Following confirmation of no reflex response, the thoracic cavity and neck were surgically opened, to expose the trachea. Bronchial fluid was collected using 4 mL of 1xPBS by an 18-gauge catheter tube from both the left and right lungs. Lavage was performed 3 times in all groups and collected in a 15 ml conical tube. The total collected BALF was centrifuged at 300 g for 5 min at 4°C to separate the cellular components from the fluid. The BALF supernatant was then 10X concentrated (cat#UFC8010, Amicon® Ultra-4 Centrifugal Filter Unit) and the total protein concentration was measured by BCA assay. BALF cytokine levels were then quantified using Rat Cytokine 27-Plex panel (RD27, Eve Technologies).

Lung tissue dissociation

The four lobes of the right lung were collected, washed in 1XPBS, and weighed. The lobes were then dissociated to a single cell suspension with Multi Tissue Dissociation Kit 2 (130-110-203, Miltenyi) according to the manufacturer’s protocol using the gentle MACS Dissociator (Miltenyi). The cell suspension was filtered through a 70 μm strainer, pelleted by centrifugation, and cleared of red blood cells with ACK Red Blood Cell Lysis buffer (BP10-548E, Lonza). Live cells were enumerated using trypan blue exclusion counting on a Countess Automated Cell Counter Hemocytometer C10227 (Invitrogen). Lung cells were then used as described below for Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) analysis. Additionally, ten million lung cells per animal were used for CD45+ enrichment using the CD45 MicroBeads kit (cat# 130-109-682, Miltenyi) per manufacturer’s instructions.

Flow cytometry analysis

Cell surface FACS analysis was performed using one million cells from either lung or BALF samples as follows. 7-AAD (420404, Bio Legend) was used to exclude dead cells. Single color tubes were used to set up a compensation matrix and a Fluorescence Minus One (FMO) control was included to ensure specific staining. The antibody staining was done at 4°C for 30 min in staining buffer (1XPBS with 2% FBS). The following anti-rat antibodies were used: APC CD45 (17-0461-82, Miltenyi), PE/CY7 CD11b (201818, Bio Legend), FITC-MHC II (205405, Bio Legend). Cell surface ACE analysis was performed using rabbit anti–rat ACE (MA5–32741, Thermo Fisher) primary antibody and goat anti-rabbit IgG-Pacific Blue (P-10994, Thermo Fisher) secondary. Sample data were acquired on a MACSQuant 10 Analyzer Flow Cytometer (Miltenyi) and analyzed using FlowJo software version 10.0 (BD Life Sciences). To verify gating and purity, all populations were routinely backgated.

Lung Immunofluorescence staining

The single left lung lobe from each animal was carefully dissected and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) overnight at 4°C, rinsed in PBS, and suspended in 30% sucrose for 24 hours. Excess sucrose was blotted off tissues prior to embedding in OCT compound on dry ice. Tissues were cryo-sectioned at four microns. Prior to staining, slides were brought to room temperature for 15 minutes, washed in PBS, and incubated for 1 hour in 2% serum in PBS to reduce non-specific binding. Sections were then incubated in anti–rat CD68 Ab (1:400; PA5-81594-Thermo Fisher) overnight at 4°C in a humid chamber. The following day, tissues were washed in PBS (3×10 min) to remove any excess antibody and incubated in Alexa-647 (1:500; A-21447- Thermo Fisher) in dark at room temperature for 1 hour. Lung sections were washed in PBS (3×10 min) and cover slipped using DAPI containing antifade mounting media (8961, Cell Signaling). Slides were viewed and photographed on EVOS M5000 Microscope (Invitrogen). Five (20×) fields from each experimental group were randomly selected and quantified by independent operators blinded to the treatment groups.

Human Monocytes

Human peripheral blood CD14+ monocytes were purchased from STEMCELL Technologies (70035.1). The human THP-1 monocyte cell line was purchased from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). Cells were maintained in RPMI-1640 medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Sigma-Aldrich), 1 μg/mL puromycin, and 0.05 mM 2-Mercaptoethanol.

Inhibitor Assays

Inhibitor treatment assays were performed on serum-starved primary monocytes or THP-1 cells. ACE ligand Angiotensin I (#1563/1, R&D) was added at a concentration of 1μM both alone and in combination with the following inhibitors: 1μM of ACE inhibitor lisinopril (21CEC PX Pharm Ltd., Sussex, UK), 10μM of the NADPH oxidase 2 (NOX2) inhibitor GSK2795039 (#SML2770G, Sigma Aldrich), and 20μM of type 1 angiotensin receptor (AGTR1) inhibitor Irbesartan (#I2286, Sigma Aldrich). Based on an established protocol in the THP-1 cell line (24), cells were exposed to 5 Gy irradiation at 2 hours following inhibitor treatment. At 24 hours post-irradiation, THP-1 or CD14+ peripheral blood cells were assessed as described below for ACE activation, MCP-1 ELISA, intracellular ROS generation, or endothelial cell adhesion.

ACE activity assay

For ACE activity within CD45+ lung cells, samples from 2–3 rat lungs within the same treatment group were pooled to obtain sufficient cell numbers. Two million cells were lysed in 0.2mL lysis buffer supplied within the kit and protein concentration was determined using the BCA method. Activity assays were performed using equivalent amounts of protein in black flat bottom 96-well plates. Tissue-specific ACE activity was performed using commercially available fluorometric ACE activity kits purchased from either Abcam (ab239703) or Sigma-Aldrich (CS0002) based on manufacturer availability. For fractionated RT samples, the Sigma kit was used, and data are represented as units of activity per microgram of protein where one unit (U) is the amount of enzyme that catalyzes the reaction of 1 nmol of substrate per minute under standard conditions. Day 70 samples from the rat PBI study were analyzed using the Abcam kit (ab239703) and data are represented as pmol/min/mg.

RT-PCR analysis

RNA isolation was performed using RNeasy Micro Kit (cat#74004, Qiagen). RNA was quantified using a Nanodrop 2000 Spectrophotometer (model- Model: 840–274200, Thermo Fisher Scientific). The synthesis of cDNA was done using the High-Capacity RNA-to-cDNA™ Kit (cat# 4387406, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Transcript expression was analyzed in triplicate using TaqMan Gene Expression Assay primer probes (cat#4331182, Thermo Fisher Scientific). The human primer probes used were ACE (Hs00174179_m1), CCL2 (Hs00234140_m1) and the reference GAPDH (Hs02786624_g1). Expression of target genes was normalized to GAPDH. The relative expression of the gene was calculated with respect to control (0 Gy) and presented as fold change (2^-(ΔCt subject)-(mean ΔCt control)), statistics done on ΔCt values.

MCP-1 ELISA

Concentrations of the human cytokine CCL2/MCP1 (chemokine ligand 2/monocyte chemoattractant protein 1) in the conditioned media from THP-1 cells were measured using Human CCL2/MCP-1 Quantikine ELISA Kit (#DCP00, R&D Systems).

Estimates of relative intracellular ROS

ROS levels following irradiation and inhibitor treatment in THP-1 cells were quantified using the CellROX green Reagent (#C10492, Thermo Fisher Scientific) per manufacturer instructions.Stained samples were analyzed on MACSQuant 10 Analyzer Flow Cytometer (Miltenyi) using the B1 (FITC) channel.

Endothelial cell adhesion assay

Monocyte adhesion to human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) was performed as previously described (25). Briefly, HUVECs were grown to confluence in 96 well flat bottom plates in EBM basal medium and were then supplemented with 50 nM TNFα for 12 hours. The HUVECs were rinsed twice with PBS and then incubated for 30 minutes with 10,000 monocytes treated as previously described in complete media. Monocytes were labeled with Calcein-AM dye (BD 564061) for fluorescent visualization and quantification. The media was aspirated, and the wells were gently washed 3 times to remove non-adherent cells. Fluorescence was measured on a Clario Star plate reader at 495/515 nm.

Statistical Analysis:

Statistical analysis was performed using the GraphPad Prism version 9 (GraphPad Software, Inc.). Data are represented as mean +/− standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical analysis of multiple groups and time points was conducted using a 2-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test. A 1-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison was used to analyze multiple groups at a single time point. P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. P values for comparison of survival curves were determined using Log rank test.

Results

Targeted Radiation Therapy (RT) Effects on the Lung Immune Compartment

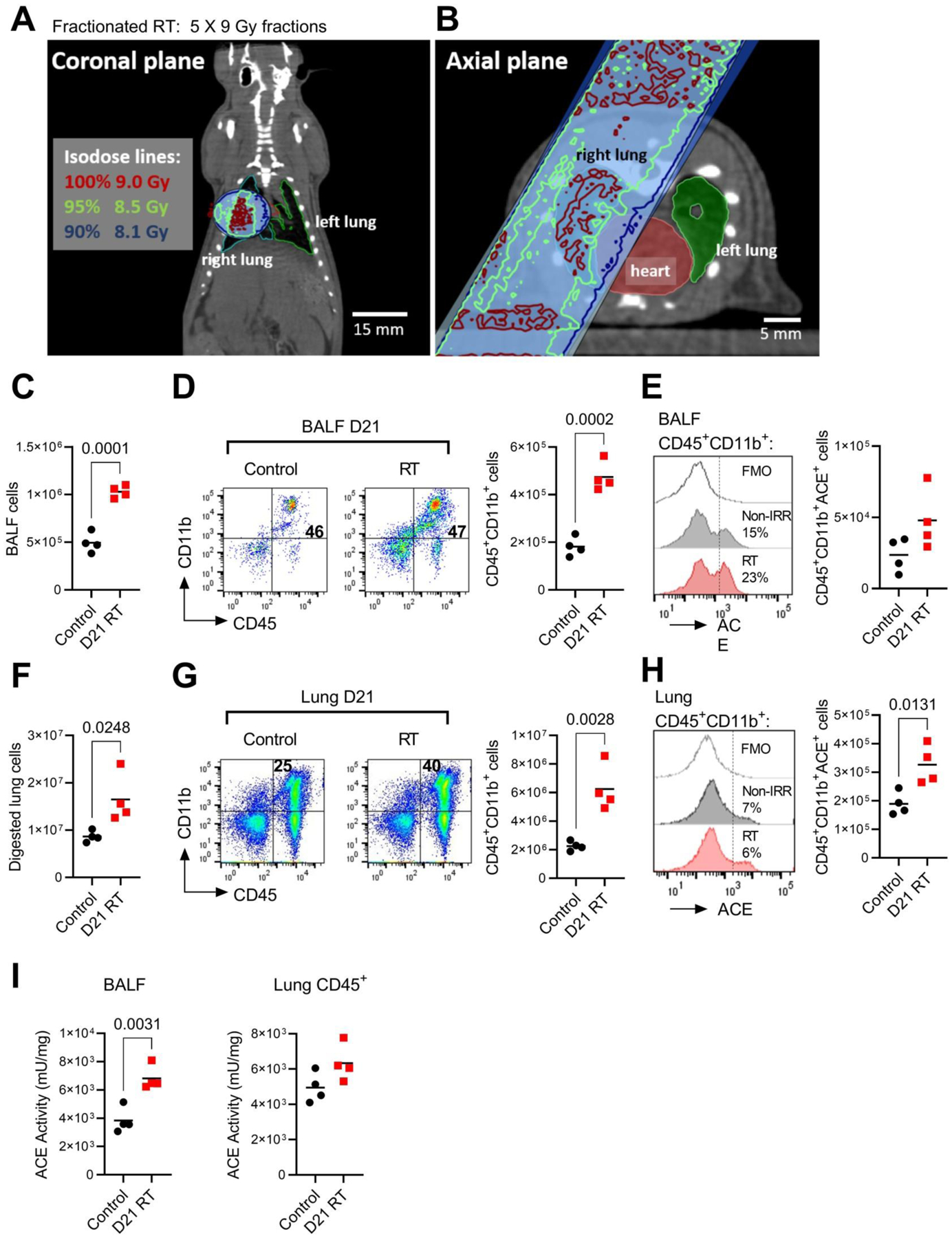

To determine the effect of localized lung radiation injury on ACE activity within the lung immune cell compartment, we evaluated lung and BALF CD45+ cells at day 21 following the initiation of fractionated RT (5 × 9 Gy) to the right lung (Fig 1A, B). This dosing schedule was designed to deliver a high total dose isolated to the right lung (45 Gy) and was based on a prior thoracic fractionated RT rat model (26). Representative coronal (Fig 1A) and axial (Fig 1B) CT images with superimposed isodose curves are shown in Figure 1. The mean dose/fraction to the heart and left lung were 2.1 and 0.2 Gy, respectively.

Fig 1. Fractionated lung RT increases ACE activity in the lung immune compartment.

(A) Representative coronal plane and (B) axial plane CT images of the radiation treatment field centered within the right lung with isodose lines. A total of four animals received 5 daily doses of 9 Gy to the treatment field in the right lung. Four control animals received sham irradiation. (C) Total cells present in the BALF at day 21 post-initiation of RT in control and RT-treated rats. (D) Left, representative FACS immunophenotype of CD45+ CD11b+ expressing BALF cells. Right, total BALF CD45+ CD11b+ cells. (E) Left, representative histogram of ACE cell surface expression by FACS within the CD45+ CD11b+ population. Right, total ACE-expressing BALF CD45+ CD11b+ cells. (F) Total viable right lung cells following enzymatic digestion in control and RT-treated rats. (G) Left, representative FACS plot of CD45+ CD11b+ expressing lung cells. Right, total lung CD45+ CD11b+ cells. (H) Left, representative histogram of ACE within the CD45+ CD11b+ lung population. Right, total lung ACE+CD45+ CD11b+ cells. (I) ACE enzymatic activity in BALF cells and CD45+ lung cells.

Rats exposed to fractionated right lung RT had increased numbers of cells present in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) compared to non-irradiated control rats (Fig 1C). Although the fraction of cells expressing FACS myeloid cell markers CD45+CD11b+ (Fig 1D, left) was similar between groups, the total number of CD45+CD11b+ myeloid cells was increased by RT treatment (Fig 1D, right). Since ACE is a membrane-bound enzyme, we also evaluated ACE cell surface expression by FACS analysis and observed a non-significant trend towards increased percentage and number of ACE-expressing myeloid cells 21 days following RT (Fig 1E).

We performed identical FACS analysis on digested lung cells from the right lung of both RT and non-irradiated control animals. RT elevated total lung cellularity (Fig 1F), the fraction of CD45+CD11b+ myeloid cells present in the lung (Fig 1G, left), and the total number of lung CD45+CD11b+ myeloid cells (Fig 1G, right). While ACE cell surface expression within the myeloid cell fraction was not different between groups (Fig 1H, left), the total number of lung ACE-expressing myeloid cells (Fig 1H, right) was significantly increased by RT treatment. Importantly, enzymatic ACE activity within both the BALF and lung CD45+ immune compartment was increased in RT-treated rats versus sham-irradiated controls (Fig 1I). Together, these data suggest RT increases the accumulation of myeloid cells with high ACE activity within the lung.

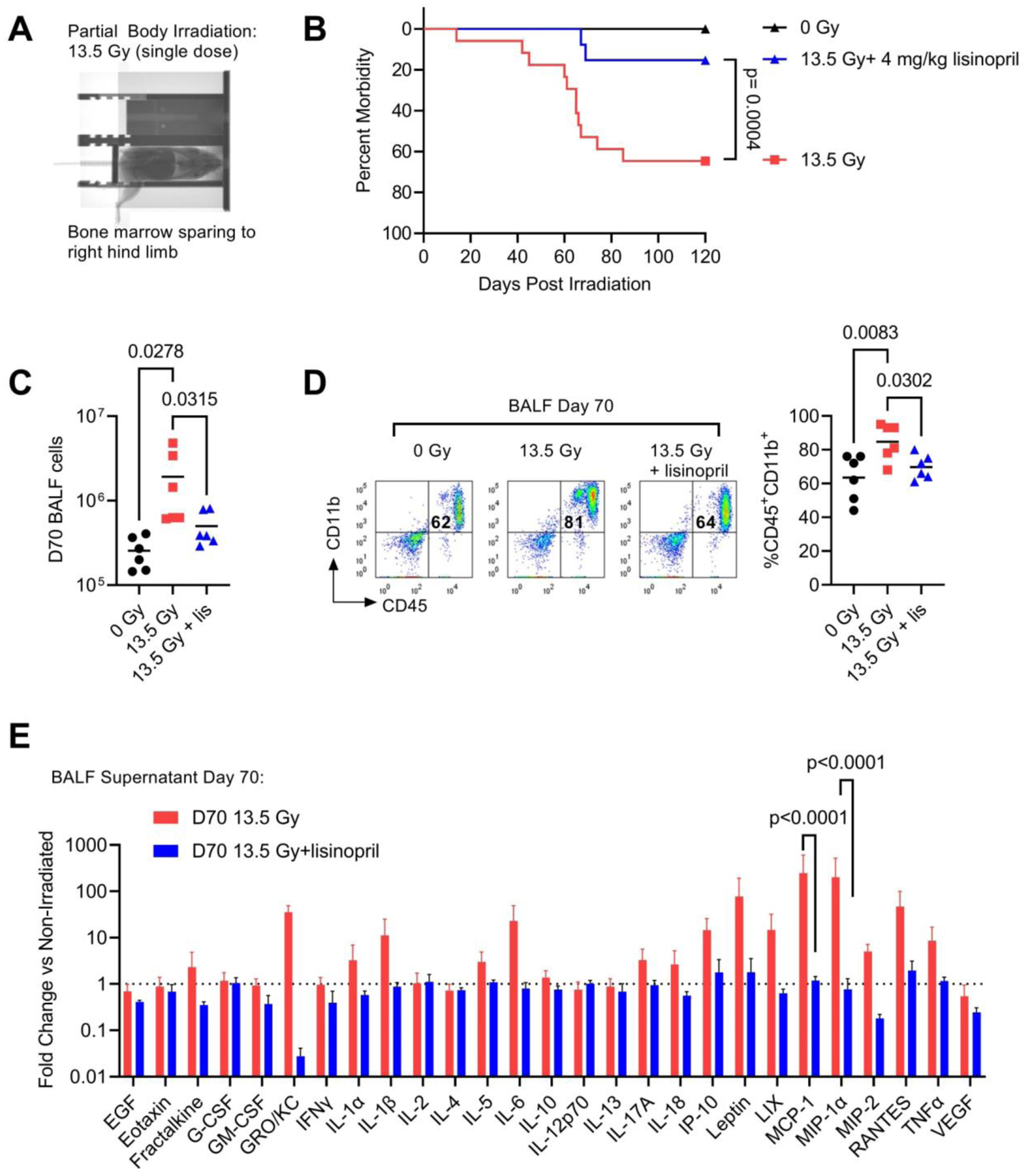

Lisinopril Improves Survival During Radiation-Induced Pneumonitis

We then used an established rat model of radiation pneumonitis to evaluate long-term effects of radiation on ACE activity in the immune compartment and the potential role of ACE-inhibitor lisinopril on immune cell function. Here, we employed a rat model of partial body irradiation (PBI) which has previously been shown to accurately reproduce multi-organ radiation injury to the bone marrow, gastrointestinal (GI) tract, lungs, heart, and kidney (12). In this model, shielding of the bone marrow in one leg (Fig 2A) and an early supportive care (SC) regimen of antibiotics and subcutaneous saline administration supports the survival of >90% of rats through early bone marrow and GI toxicities. At days 50–120 post-injury, rats typically develop complications of pneumonitis as characterized by rapid respiration, weight loss and pleural effusion. In this model, we have evaluated the effect of daily ACE inhibitor treatment on survival during pneumonitis. We observed significant lung morbidity exhibited by rapid respiration and pleural effusion in the irradiated control group during days 50–120 post-irradiation. Median survival in irradiated non-treated animals was 67 days with only 35% of animals (6/17) surviving through day 120 (Fig 2B). Administration of lisinopril in the drinking water (days 2 to study endpoint) significantly improved survival through day 120 with 85% of lisinopril animals (11/13) surviving (Fig 2B). For analysis of the immune cell compartment near the median survival time for untreated animals during pneumonitis, we performed terminal assessments at day 70 post-13.5 Gy PBI.

Fig 2. ACE inhibition improves survival during radiation pneumonitis and suppresses pro-inflammatory immune cells.

(A) Representative X-ray image of rat partial body irradiation model with shielding to one hind limb. (B) Survival through 120 days in adult female WAG/RijCmcr rats irradiated with 13.5 Gy PBI with or without lisinopril treatment. Survival in control 13.5 Gy animals was 35% (6/17) and 85% (11/13) in lisinopril treated rats (4 mg/kg). (C) Total cells present within the BALF at day 70- post irradiation (n=6 rats per treatment group). (D) Left, representative FACS profile showing the percentage of CD45+CD11b+ myeloid cells in the 0 Gy, 13.5 Gy and 13.5 Gy + lisinopril treatment groups at 70-days post irradiation. Right, quantification of the percent CD45+CD11b+ cells. (E) Multiplex cytokine analysis of the 10X concentrated BALF supernatant at 70-days post irradiation. Data are shown as fold change relative to the mean non-irradiated level for each cytokine (n=6 rats for each group). For all graphs, error bars indicate SEM.

Lisinopril Mitigates Accumulation of Pro-inflammatory Immune Cells in the Bronchoalveolar Lavage Fluid

Similar to the RT model, we observed 13.5 Gy PBI increased the accumulation of cells in the BALF at day 70 following radiation (Fig 2C). Daily treatment with lisinopril significantly reduced the total number of BALF cells (Fig 2C). FACS analysis of the BALF cell fraction at day 70 demonstrated an increase in the proportion of BALF cells expressing myeloid cell markers CD45+CD11b+ (Fig 2D) in irradiated rats. Lisinopril suppressed the radiation-induced increase in CD45+CD11b+ cells present in the BALF (Fig 2D). We then characterized the profile of a panel of 27 rat cytokines present in the BALF at day 70 post-injury (Fig 2E). Here, we have normalized the protein level of each cytokine to the non-irradiated protein level, so the data are represented as a fold-change versus non-irradiated control (Fig 2E, dotted line). Radiation markedly (~100-fold) increased the levels of inflammatory cytokines MCP-1 (CCL2) and MIP-1α (CCL3); however, treatment with lisinopril reduced cytokines levels to baseline (Fig 2E).

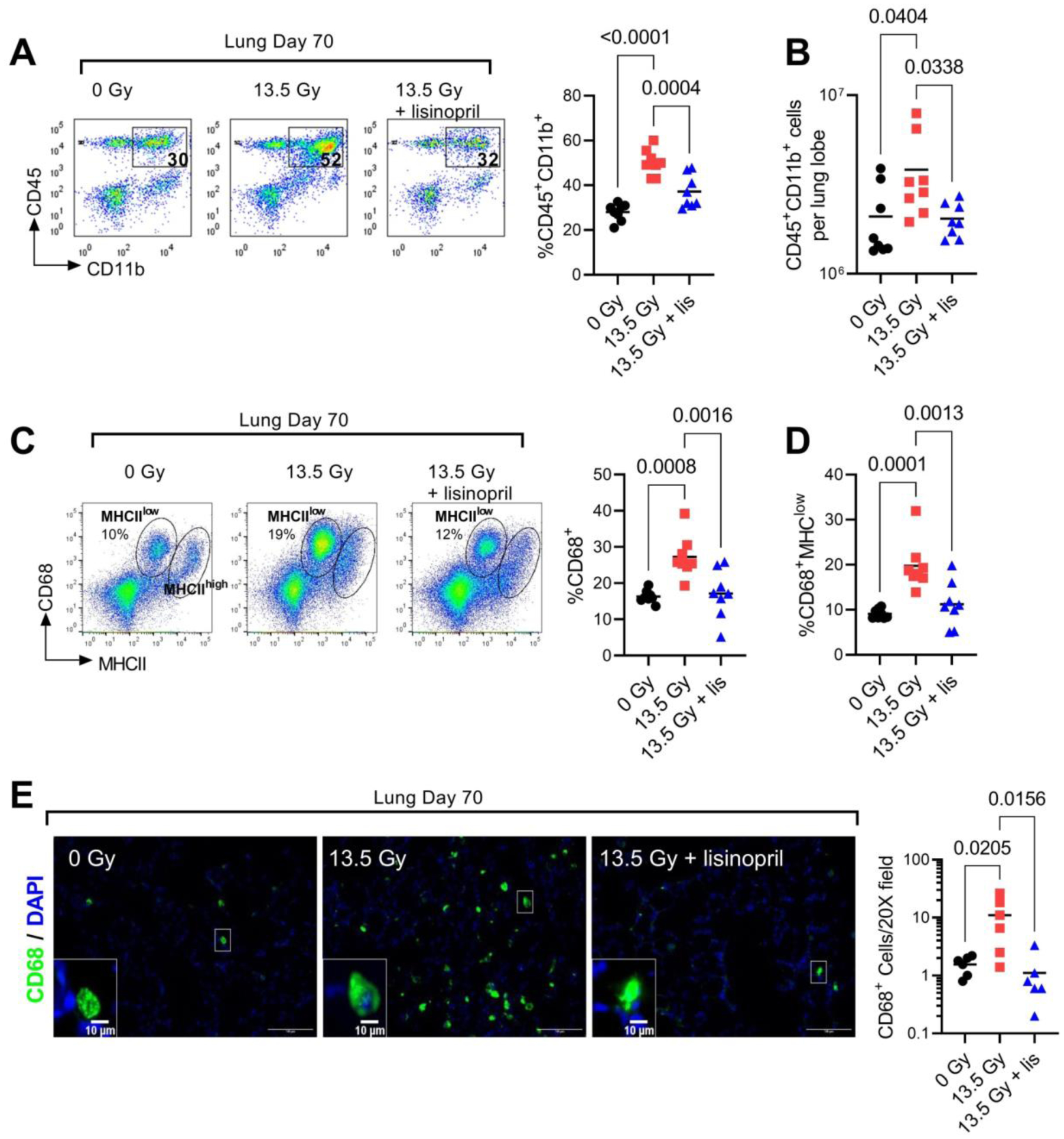

Lisinopril Reduces Accumulation of Pro-inflammatory Immune Cells in the Lung

We next assessed the accumulation of immune cell subsets in the lung during pneumonitis. At day 70 following injury, there was no difference in the total number of dissociated lung cells between groups. However, in the irradiated group, approximately 50% of the dissociated lung cells analyzed express myeloid markers CD45+CD11b+ compared to only 27% in the non-irradiated group and 37% in irradiated animals treated with lisinopril (Fig 3A). In a complementary cohort of male rats irradiated with 13 Gy PBI (Fig S1), lisinopril treatment similarly reduced the radiation-induced accumulation of CD45+CD11b+ cells in the lung. Thus, lisinopril treatment significantly reduced the total number of CD45+CD11b+ myeloid cells present in the lung (Fig 3B).

Fig 3. Lisinopril blocks radiation-induced infiltration of myeloid cell subsets at day 70 after PBI.

(A) Left, representative FACS profile showing the percentage of CD45+ CD11b+ lung myeloid cells in 0 Gy, 13.5 Gy and 13.5 Gy + lisinopril groups. Right, quantification of percent CD45+ CD11b+ cells (n=8 rats per group). (B) Total CD45+ CD11b+ myeloid cells in a single lung lobe. (C) Left, representative FACS profile of CD68 and MHCII expression within the CD45+ CD11b+ lung population. Right, quantification of the percent CD68+ cells determined from the sum of the highlighted regions. (D) Quantification of CD68+MHCIlow cell population. (E) Left, representative 20X IF fields of CD68 (green) and DAPI (blue) stained lung sections. Inset box at lower left is a digital magnification of the indicated region to illustrate the morphology of the CD68+ cells. Right, mean number of CD68+ cells per field. Each data point represents the mean of five fields from one lung (n=6 rat lungs per group).

We performed additional immunophenotyping to determine expression of monocyte/macrophage markers CD68 and major histocompatibility complex class II (MHCII) within the CD45+CD11b+ population. Radiation significantly increased the total percentage of CD68+ cells (Fig 3C). Within the CD68+ cell population, two distinct subsets of MHCII expressing cells were observed (Fig 3C). The subset of CD68+ cells with lower MHCII expression (MHCIIlow) was significantly increased by radiation and the increase was suppressed with lisinopril treatment (Fig 3D). The subset of CD68+ cells with higher MHCII expression (MHCIIhigh) were not affected by either radiation or lisinopril. Based on prior reports (27) we surmise the MHCIIhigh cells may represent a population of myeloid dendritic cells. To discriminate these cell types based on morphology, we then evaluated the CD68+ population by immunofluorescent imaging (Fig 3E). We observed an increase in the total number of CD68+ cells in the irradiated treated group (Fig 3E). Lisinopril blocked the radiation-induced increase in CD68+ cells. Morphologically, the CD68+ cells appear rounded rather than stellate which is consistent with a macrophage phenotype.

Lung Immune ACE Expression and Activity are Elevated During Pneumonitis

ACE activity in whole lung lysates was elevated in animals treated with 13.5 Gy PBI at day 70 versus non-irradiated controls (Fig 4A). Lisinopril treatment in vivo significantly reduced radiation-induced ACE enzymatic activity (Fig 4A). To determine if lisinopril treatment specifically reduces ACE activity within immune cell subsets, we assessed radiation-induced changes in ACE expression and activity within isolated lung CD45+ cells. We first evaluated ACE cell surface expression by FACS analysis and observed a significant increase in ACE cell surface expression on CD45+CD11b+ immune cells which was abrogated in irradiated rats treated with lisinopril (Fig 4B). We next determined ACE enzymatic activity in column purified CD45+ lung cells and observed in vivo lisinopril treatment reduced ACE activity within this immune cell population (Fig 4C).

Fig 4. Lisinopril blocks radiation-induced ACE activation in lung immune cells at day 70 post-PBI.

(A) Whole lung ACE activity represented as mU/mg of lung tissue (n=7–8 per group). (B) Left, representative FACS histogram of ACE expression on cells gated from the CD45+ CD11b+ lung cell population. Fluorescence Minus One (FMO) control was used to set the gates. Right, quantification of percent ACE+ within the CD45+ CD11b+ lung cell population (n=7 per group). (C) Lung CD45+ ACE activity. Each data point represents independent biological replicates of pooled CD45+ cells from 2–3 rats.

Radiation-Induced ACE Activation in THP-1 cells Increases MCP-1 Secretion and Monocyte Adhesion

To determine if radiation directly regulates ACE activity and downstream signaling in immune cells, we performed the following in vitro analyses in the human monocytic THP-1 cell line. Exposure of THP-1 cultures to 5 Gy increased both ACE enzymatic activity nearly 10-fold (Fig 5A) and more than doubles ACE mRNA expression (Fig 5B). The addition of lisinopril to the culture medium as expected significantly suppressed radiation-induced ACE activity (Fig 5A). To validate the radiation-induced increase in MCP-1 (CCL2) protein observed in vivo, we examined radiation induced changes in MCP-1 secretion and expression in the THP-1 cell line. In THP-1 cells, exposure to 5 Gy increased both the transcription (Fig 5B) and protein secretion (Fig 5C) of MCP-1/CCL2. Lisinopril reduced both mRNA expression (Fig 5B) and MCP-1secretion (Fig 5C) in THP-1 cells. Since MCP-1 promotes monocyte adherence to the vascular endothelium, we then assessed the effects of radiation and lisinopril treatment on THP-1 cell adhesion to human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs). Here, lisinopril treatment abrogated the radiation-induced increase in THP-1 cell adherence (Fig 5D).

Fig 5. Radiation-induced ACE activation directly promotes MCP-1 expression and monocyte adherence.

(A) ACE enzymatic activity in THP-1 cultures at 24 hours following treatment with 0 Gy, 5 Gy, or 5 Gy + 1μM of lisinopril (n=3 independent cultures per treatment group). (B) mRNA expression of ACE and MCP-1/CCL2 in THP-1 cultures at 24 hours following treatment with 0 Gy, 5 Gy, or 5 Gy + 1μM of lisinopril (n=3–7 independent cultures per treatment group). Data are represented as fold change relative to the 0 Gy group. (C) Secreted MCP-1/CCL2 cytokine levels measured by ELISA in THP-1 culture medium at 24 hours following treatment with 0 Gy, 5 Gy, or 5 Gy + 1μM of lisinopril (n=3 independent cultures per treatment group). (D) Number of THP-1 monocytes adhered to HUVEC monolayer at 24 hours following treatment with 0 Gy, 5 Gy, or 5 Gy + 1μM of lisinopril (n=6 independent cultures per treatment group).

ACE Promotes ROS Generation via Downstream Activation of AT1R and Nox2

In vitro radiation exposure induces an increase in THP-1 ROS generation, which is reduced to non-irradiated levels by lisinopril treatment (Fig 6A). Canonically, ACE catalyzes the cleavage of angiotensin I (AngI) to angiotensin II (AngII). In vascular cells, it is well-established that Ang II/Agtr1 signaling increases ROS generation via activation of the membrane bound NAD(P)H oxidase (28). Monocytes and macrophages specifically express the NOX2 isoform of NAD(P)H oxidase. To determine if downstream activation of AGTR1 and NOX2 are necessary for ACE-mediated ROS generation, we added pharmacological inhibitors of AGTR1 (Irbesartan) and NOX2 (GSK2795039) to the irradiated THP-1 cell line. Inhibition of either AGTR1 or NOX2 blocked radiation-induced ROS generation in a similar manner as lisinopril treatment (Fig 6B). We then validated this finding using cultures of primary human peripheral blood CD14+ monocytes. Consistent with the cell line study, radiation promoted ROS generation in primary monocytes (Fig 6C). ROS generation was abrogated by pharmacological blockade of ACE, NOX2 or AGTR1 (Fig 6C).

Fig 6. Radiation-induced ACE activation promotes ROS generation via NOX2.

(A) Left, representative FACS histogram of CellRox+ THP-1 cells at 24 hours following treatment with 0 Gy, 5 Gy, or 5 Gy + 1μM of lisinopril. Right, mean percentage of CellRox+ cells (n=4–6 independent cultures per treatment group). (B) CellRox+ THP-1 cells at 24 hours following treatment with 0 Gy, 5 Gy, or 5 Gy + GSK2795039 (NOX2 inhibitor) or 5 Gy + 20μM of Irbesartan (AGTR1 inhibitor), (n=3 independent cultures per treatment group). (C) CellRox+ primary human monocytes cells at 24 hours following treatment with 0 Gy, 5 Gy, 5 Gy + lisinopril, 5 Gy + GSK2795039 (NOX2 inhibitor), or 5 Gy + 20μM of Irbesartan (AGTR1 inhibitor), (n=3 independent cultures per treatment group).

Discussion

ACE inhibitor treatment has well-established function as a vasodilator and a suppressor of reactive oxygen species production in vascular pharmacology (29). While these angio-protective effects are likely to promote multi-organ recovery following radiation injury, here we demonstrate ACE inhibitor treatment also directly regulates the function of irradiated immune cells. In both lung injury models tested, we observed an increase in CD45+CD11b+ myeloid cells present in the lung. The rise in this cell population likely represents the infiltration of inflammatory monocytes and macrophages as upregulation of pan-myeloid cell marker CD11b in lung neutrophils and macrophage populations has been correlated with increased inflammatory state (30,31). In our PBI model of radiation pneumonitis, we observed an increase in myeloid cell surface expression of ACE at day 70. Importantly, ACE inhibition with lisinopril represses myeloid cell accumulation in the lung and the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines MCP-1 (CCL2) and MIP1α (CCL3). These results are consistent with prior publications demonstrating ACE inhibitor captopril reduces activated macrophage recruitment to the lung in irradiated rats (32) and mice (4).

The observation that ACE inhibition suppresses inflammatory cell accumulation in the lung in the PBI model is an important clinical finding as dysfunction of the immune microenvironment is known to play a key role in exacerbating lung injury. Lung-infiltrating immune cells promote both acute pneumonitis via release of inflammatory cytokines IL-3, IL-6, IL-7, TNF-α (33) and chronic irreversible fibrosis via secretion of pro-fibrotic cytokine TGF-β (34). In mice, irradiation of the whole thorax results in a remodeling of the lung immune microenvironment characterized by an acute loss in resident alveolar macrophages and a shift towards a pro-inflammatory phenotype in repopulating macrophages (35). A recent transcriptomic study on nonhuman primates reveals that whole-thorax irradiation induces genes promoting macrophage polarization and activation of TGF-β in the progression of RILI (36). Moreover, tissue-specific deletion of chemokine receptor and pro-inflammatory monocyte marker CCR2 reduces pulmonary fibrosis in irradiated mice (37), demonstrating infiltrating monocytes play a key role in the progression of RILI.

While our data are the first to define a role for immune cell ACE in the pathogenesis of RILI, a growing body of evidence supports a regulatory role for ACE in primitive human hematopoiesis (38–41), myeloproliferative disorders(42,43), and peripheral blood monocyte function(44). In mouse models, loss of ACE blocks normal myelopoiesis and prevents macrophage differentiation (16). Importantly, enforced expression of ACE in mouse macrophages enhances immune function in experimental models of bacterial infection (18) and atherosclerosis (17). In circulating human monocyte populations, ACE activity and expression are elevated in classical CD14+CD16− monocytes (44). Additionally, ACE activity increases as human monocytes differentiate to macrophages (45,46). In lung cancer patient samples, ACE is strongly expressed in lung-infiltrating macrophages (47).

Our in vivo data suggest ACE-expressing lung-infiltrating myeloid cells promote RILI pathogenesis as we observe an increase in lung CD45+CD11b+ myeloid cells that is abrogated by treatment with lisinopril. To understand how ACE-activation within monocyte populations promotes RILI, we performed in vitro analysis of irradiated human monocytes. Here, consistent with our in vivo data, we observed radiation injury directly promotes monocyte expression of adhesion molecule MCP-1 (CCL2) and adherence to endothelial monolayers. Treatment with lisinopril suppressed both in vivo and in vitro MCP-1 production and in vitro monocyte adhesion. Therefore, lisinopril may be suppressing the pathogenesis of radiation pneumonitis in part by reducing the recruitment and retention of monocytes in the lung.

Lisinopril may also be mediating a pro-survival benefit during RILI through the suppression of radiation-induced ROS species. Pharmacologic reduction of ROS with the SOD mimetic EUK-207 has previously been shown to mitigate pneumonitis and pulmonary fibrosis following whole thorax irradiation in rats (48). Here, we observed in vitro irradiation of monocytes directly elevates both ACE activity and generation of ROS, while inhibition of ACE with lisinopril suppresses ACE activity and ROS production. Blockade of the type 1 Ang II receptor AGTR1 also inhibits radiation-induced ROS generation suggesting radiation-induced ACE activation promotes canonical AngII/AGTR1 signaling. ACE mediated activation of AGTR1 is known to regulate radiation-induced renal injury, as pharmacologic inhibition of either ACE or AGTR1 mitigates renal nephropathy in irradiated rat models (49). Additionally, we show blockade of NOX2 similarly inhibits radiation-induced ROS generation. Together with our in vivo data, these data suggest ACE-mediated NOX2 activation and subsequent ROS generation plays a key role in the progression of radiation pneumonitis. This finding is supported by the observation that Nox2 mRNA levels are elevated in rat lungs following thoracic irradiation (50). Additionally, Nox2-expressing myeloid cells are known to play a key role in mediating the pathogenesis of heart failure (51) and hypertension (52) in murine models. These findings imply the observed benefit of lisinopril in mitigation of radiation induced cardiotoxicity (8) and nephropathy (11) may be in part due to suppression of ACE-mediated ROS generation in immune cell populations; however, this would require experimental validation.

Another important consideration in the pathogenesis of RILI is concurrent radiation injury to the heart as the manifestation of radiation pneumonitis in patient populations is highly correlated with dose to the heart (53,54). In the current study, the heart was exposed to doses of either 13.5 Gy (PBI model) or 5 fractions of 2.1 Gy (RT model). As prior experimental models demonstrate co-irradiation of the heart and lung exacerbates radiation-induced loss of respiratory function (55–58), it will be necessary to determine if injury to the heart may modulate the ACE-mediated mechanisms described here. Indeed, it is likely that radiation exposure to the heart at these doses may be contributing to release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and ROS (59).

This study supports the further development of lisinopril for use as an emergency countermeasure for victims of accidental radiation exposure and importantly identifies the target cell and mechanism of action in the mitigation of RILI. Additionally, our fractionated RT model suggests lisinopril may have broader use for the treatment of radiation pneumonitis in cancer patients undergoing thoracic RT. Indeed, a retrospective analysis of lung cancer patients receiving RT demonstrated the incidental use of ACE inhibitors was associated with reduced pulmonary toxicity (13). Two prior clinical trials (60,61) were initiated to evaluate the safety and efficacy of ACE inhibitors for mitigation of pulmonary toxicity in lung cancer patients. Although both trials failed to accrue enough patients to evaluate efficacy, the use of either lisinopril (61) or captopril (60) had favorable safety profiles. An important consideration for the future use of ACE inhibitors for mitigation of off-target lung toxicity is the potential effect on the tumor microenvironment as modulation of the local renin-angiotensin system has been shown to have both pro- and anti- tumor effects (62).

Conclusion

This study is the first to demonstrate ACE activity within the lung immune cell compartment plays a role in the pathogenesis of RILI. In rats exposed to high-dose PBI, ACE inhibitors directly suppress radiation-induced immune cell ACE activation and subsequent pro-inflammatory response. Complementary in vitro studies suggest radiation-induced ACE activation promotes RILI via AGTR1/NOX2 signaling and subsequent ROS generation.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Fig 1. Lisinopril blocks radiation-induced infiltration of myeloid cell subsets at day 70 post-13 Gy in adult male rats. Percentage of CD45+ CD11b+ lung-infiltrating myeloid cells in 0 Gy, 13 Gy and 13 Gy + lisinopril groups (n = 4 male rats per treatment group).

Funding Statement

This work was supported by funding from NIH/NIAID U01AI133594, U01AI138331, the MCW Department of Radiation Oncology, and the MCW Cancer Center.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest: None.

Data Availability Statement for this Work

Research data are stored in an institutional repository and will be shared upon request to the corresponding author.

References

- 1.Hanania AN, Mainwaring W, Ghebre YT, et al. Radiation-induced lung injury: Assessment and management. Chest 2019;156:150–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Medhora M, Gao F, Jacobs ER, et al. Radiation damage to the lung: Mitigation by angiotensin-converting enzyme (ace) inhibitors. Respirology 2012;17:66–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beach TA, Groves AM, Williams JP, et al. Modeling radiation-induced lung injury: Lessons learned from whole thorax irradiation. Int J Radiat Biol 2020;96:129–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Williams JP, Johnston CJ, Finkelstein JN. Treatment for radiation-induced pulmonary late effects: Spoiled for choice or looking in the wrong direction? Curr Drug Targets 2010;11:1386–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCart EA, Lee YH, Jha J, et al. Delayed captopril administration mitigates hematopoietic injury in a murine model of total body irradiation. Sci Rep 2019;9:2198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mungunsukh O, George J, McCart EA, et al. Captopril reduces lung inflammation and accelerated senescence in response to thoracic radiation in mice. J Radiat Res 2021;62:236–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Medhora M, Gao F, Gasperetti T, et al. Delayed effects of acute radiation exposure (deare) in juvenile and old rats: Mitigation by lisinopril. Health Phys 2019;116:529–545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van der Veen SJ, Ghobadi G, de Boer RA, et al. Ace inhibition attenuates radiation-induced cardiopulmonary damage. Radiother Oncol 2015;114:96–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ryu S, Kolozsvary A, Jenrow KA, et al. Mitigation of radiation-induced optic neuropathy in rats by ace inhibitor ramipril: Importance of ramipril dose and treatment time. J Neurooncol 2007;82:119–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim JH, Brown SL, Kolozsvary A, et al. Modification of radiation injury by ramipril, inhibitor of angiotensin-converting enzyme, on optic neuropathy in the rat. Radiat Res 2004;161:137–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moulder JE, Fish BL, Cohen EP. Treatment of radiation nephropathy with ace inhibitors and aii type-1 and type-2 receptor antagonists. Curr Pharm Des 2007;13:1317–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fish BL, Gao F, Narayanan J, et al. Combined hydration and antibiotics with lisinopril to mitigate acute and delayed high-dose radiation injuries to multiple organs. Health Phys 2016;111:410–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kharofa J, Cohen EP, Tomic R, et al. Decreased risk of radiation pneumonitis with incidental concurrent use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and thoracic radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2012;84:238–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ghosh SN, Wu Q, Mader M, et al. Vascular injury after whole thoracic x-ray irradiation in the rat. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2009;74:192–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cao DY, Saito S, Veiras LC, et al. Role of angiotensin-converting enzyme in myeloid cell immune responses. Cell Mol Biol Lett 2020;25:31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin C, Datta V, Okwan-Duodu D, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme is required for normal myelopoiesis. FASEB J 2011;25:1145–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Okwan-Duodu D, Weiss D, Peng Z, et al. Overexpression of myeloid angiotensin-converting enzyme (ace) reduces atherosclerosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2019;520:573–579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Okwan-Duodu D, Datta V, Shen XZ, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme overexpression in mouse myelomonocytic cells augments resistance to listeria and methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus. J Biol Chem 2010;285:39051–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kohlstedt K, Trouvain C, Namgaladze D, et al. Adipocyte-derived lipids increase angiotensin-converting enzyme (ace) expression and modulate macrophage phenotype. Basic Res Cardiol 2011;106:205–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gasperetti T, Miller T, Gao F, et al. Polypharmacy to mitigate acute and delayed radiation syndromes. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2021;12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fish BL, Gao F, Narayanan J, et al. Combined hydration and antibiotics with lisinopril to mitigate acute and delayed high-dose radiation injuries to multiple organs. Health Phys 2016;111:410–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Song J-A, Yang H-S, Lee J, et al. Standardization of bronchoalveolar lavage method based on suction frequency number and lavage fraction number using rats. Toxicol Res 2010;26:203–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Szabo S, Ghosh SN, Fish BL, et al. Cellular inflammatory infiltrate in pneumonitis induced by a single moderate dose of thoracic x radiation in rats. Radiation research 2010;173:545–556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yoshino H, Kashiwakura I. Involvement of reactive oxygen species in ionizing radiation-induced upregulation of cell surface toll-like receptor 2 and 4 expression in human monocytic cells. J Radiat Res 2017;58:626–635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilhelmsen K, Farrar K, Hellman J. Quantitative in vitro assay to measure neutrophil adhesion to activated primary human microvascular endothelial cells under static conditions. J Vis Exp 2013:e50677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schlaak RA, Frei A, Schottstaedt AM, et al. Mapping genetic modifiers of radiation-induced cardiotoxicity to rat chromosome 3. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2019;316:H1267–H1280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zaynagetdinov R, Sherrill TP, Kendall PL, et al. Identification of myeloid cell subsets in murine lungs using flow cytometry. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2013;49:180–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nguyen Dinh Cat A, Montezano AC, Burger D, et al. Angiotensin ii, nadph oxidase, and redox signaling in the vasculature. Antioxid Redox Signal 2013;19:1110–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schramm A, Matusik P, Osmenda G, et al. Targeting nadph oxidases in vascular pharmacology. Vascul Pharmacol 2012;56:216–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stockfelt M, Christenson K, Andersson A, et al. Increased cd11b and decreased cd62l in blood and airway neutrophils from long-term smokers with and without copd. J Innate Immun 2020;12:480–489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Duan M, Steinfort DP, Smallwood D, et al. Cd11b immunophenotyping identifies inflammatory profiles in the mouse and human lungs. Mucosal Immunol 2016;9:550–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mahmood J, Jelveh S, Zaidi A, et al. Targeting the renin-angiotensin system combined with an antioxidant is highly effective in mitigating radiation-induced lung damage. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2014;89:722–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Giuranno L, Ient J, De Ruysscher D, et al. Radiation-induced lung injury (rili). Front Oncol 2019;9:877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jin H, Yoo Y, Kim Y, et al. Radiation-induced lung fibrosis: Preclinical animal models and therapeutic strategies. Cancers (Basel) 2020;12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Groves AM, Johnston CJ, Misra RS, et al. Whole-lung irradiation results in pulmonary macrophage alterations that are subpopulation and strain specific. Radiat Res 2015;184:639–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thakur P, DeBo R, Dugan GO, et al. Clinicopathologic and transcriptomic analysis of radiation-induced lung injury in nonhuman primates. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2021;111:249–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Groves AM, Johnston CJ, Williams JP, et al. Role of infiltrating monocytes in the development of radiation-induced pulmonary fibrosis. Radiat Res 2018;189:300–311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goker H, Haznedaroglu IC, Beyazit Y, et al. Local umbilical cord blood renin-angiotensin system. Ann Hematol 2005;84:277–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jokubaitis VJ, Sinka L, Driessen R, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme (cd143) marks hematopoietic stem cells in human embryonic, fetal, and adult hematopoietic tissues. Blood 2008;111:4055–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sinka L, Biasch K, Khazaal I, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme (cd143) specifies emerging lymphohematopoietic progenitors in the human embryo. Blood 2012;119:3712–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zambidis ET, Park TS, Yu W, et al. Expression of angiotensin-converting enzyme (cd143) identifies and regulates primitive hemangioblasts derived from human pluripotent stem cells. Blood 2008;112:3601–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aksu S, Beyazit Y, Haznedaroglu IC, et al. Over-expression of angiotensin-converting enzyme (cd 143) on leukemic blasts as a clue for the activated local bone marrow ras in aml. Leuk Lymphoma 2006;47:891–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Marusic-Vrsalovic M, Dominis M, Jaksic B, et al. Angiotensin i-converting enzyme is expressed by erythropoietic cells of normal and myeloproliferative bone marrow. Br J Haematol 2003;123:539–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rutkowska-Zapala M, Suski M, Szatanek R, et al. Human monocyte subsets exhibit divergent angiotensin i-converting activity. Clin Exp Immunol 2015;181:126–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Danilov SM, Sadovnikova E, Scharenborg N, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme (cd143) is abundantly expressed by dendritic cells and discriminates human monocyte-derived dendritic cells from acute myeloid leukemia-derived dendritic cells. Exp Hematol 2003;31:1301–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Friedland J, Setton C, Silverstein E. Induction of angiotensin converting enzyme in human monocytes in culture. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1978;83:843–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Danilov SM, Metzger R, Klieser E, et al. Tissue ace phenotyping in lung cancer. PLoS One 2019;14:e0226553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gao F, Fish BL, Szabo A, et al. Short-term treatment with a sod/catalase mimetic, euk-207, mitigates pneumonitis and fibrosis after single-dose total-body or whole-thoracic irradiation. Radiat Res 2012;178:468–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Moulder JE, Cohen EP, Fish BL. Captopril and losartan for mitigation of renal injury caused by single-dose total-body irradiation. Radiat Res 2011;175:29–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Najafi M, Shirazi A, Motevaseli E, et al. Evaluating the expression of nox2 and nox4 signaling pathways in rats’ lung tissues following local chest irradiation; modulatory effect of melatonin. Int J Mol Cell Med 2018;7:220–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Molitor M, Rudi WS, Garlapati V, et al. Nox2+ myeloid cells drive vascular inflammation and endothelial dysfunction in heart failure after myocardial infarction via angiotensin ii receptor type 1. Cardiovasc Res 2021;117:162–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Abais-Battad JM, Lund H, Dasinger JH, et al. Nox2-derived reactive oxygen species in immune cells exacerbates salt-sensitive hypertension. Free Radic Biol Med 2020;146:333–339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yorke ED, Jackson A, Kuo LC, et al. Heart dosimetry is correlated with risk of radiation pneumonitis after lung-sparing hemithoracic pleural intensity modulated radiation therapy for malignant pleural mesothelioma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2017;99:61–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Huang EX, Hope AJ, Lindsay PE, et al. Heart irradiation as a risk factor for radiation pneumonitis. Acta Oncol 2011;50:51–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.van Luijk P, Faber H, Meertens H, et al. The impact of heart irradiation on dose-volume effects in the rat lung. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2007;69:552–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.van Luijk P, Novakova-Jiresova A, Faber H, et al. Radiation damage to the heart enhances early radiation-induced lung function loss. Cancer Res 2005;65:6509–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ghobadi G, van der Veen S, Bartelds B, et al. Physiological interaction of heart and lung in thoracic irradiation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2012;84:e639–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schlaak RA, SenthilKumar G, Boerma M, et al. Advances in preclinical research models of radiation-induced cardiac toxicity. Cancers (Basel) 2020;12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sarkozy M, Varga Z, Gaspar R, et al. Pathomechanisms and therapeutic opportunities in radiation-induced heart disease: From bench to bedside. Clin Res Cardiol 2021;110:507–531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Small W Jr., James JL, Moore TD, et al. Utility of the ace inhibitor captopril in mitigating radiation-associated pulmonary toxicity in lung cancer: Results from nrg oncology rtog 0123. Am J Clin Oncol 2018;41:396–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sio TT, Atherton PJ, Pederson LD, et al. Daily lisinopril vs placebo for prevention of chemoradiation-induced pulmonary distress in patients with lung cancer (alliance mc1221): A pilot double-blind randomized trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2019;103:686–696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Catarata MJ, Ribeiro R, Oliveira MJ, et al. Renin-angiotensin system in lung tumor and microenvironment interactions. Cancers (Basel) 2020;12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Fig 1. Lisinopril blocks radiation-induced infiltration of myeloid cell subsets at day 70 post-13 Gy in adult male rats. Percentage of CD45+ CD11b+ lung-infiltrating myeloid cells in 0 Gy, 13 Gy and 13 Gy + lisinopril groups (n = 4 male rats per treatment group).

Data Availability Statement

Research data are stored in an institutional repository and will be shared upon request to the corresponding author.