Abstract

Background:

To allay uneasiness among clinicians and institutional review board members about pediatric palliative care research and to yield new knowledge relevant to study methods, documenting burdens and benefits of this research on children and their families is essential.

Design:

In a grounded theory study with three data points (T1, T2, and T3), we evaluated benefits and burdens of family caregiver participation at T3. English-speaking caregivers participating in palliative or end-of-life decisions for their child with incurable cancer or their seriously ill child in the intensive care unit participated. Thirty-seven caregivers (n = 22 from oncology; n = 15 from intensive care) of 33 children completed T3 interviews; most were mothers (n = 25, 67.6%), African American (n = 18, 48.6%), and married (n = 28, 75.7%).

Measurement:

Benefits and burdens were assessed by three open-ended questions asked by an interviewer during a scheduled telephone contact. Responses were analyzed using descriptive semantic content analysis techniques and themes were extracted.

Results:

All 37 T3 participants completed the 3 questions, resulting in no missing data. The most frequently reported themes were of positive personal impact: “Hoping to help others,” “Speaking about what is hard is important,” and “Being in the study was sometimes hard but not bad.”

Conclusions:

No caregiver described the study as burdensome. Some acknowledged that answering the questions could evoke sad memories, but highlighted benefits for self and others. Attrition somewhat tempers the emphasis on benefits. Documenting perceived benefits and burdens in a standardized manner may accurately convey impact of study participation and yield new knowledge.

Keywords: benefits and burdens, end-of-life research, palliative care research, pediatrics

Background

Pediatric palliative care depends in part on research to continue advancing care effectiveness for seriously ill children and their families.1 Needed are studies that address high priority areas in clinical care with a focus on not harming or burdening the ill child or family, and conducted in a scientifically sound manner. Studies with these characteristics are likely to yield clinically useful findings. Palliative care research studies involving ill children and family caregivers (caregivers) are cautiously reviewed for presumed burden by institutional review board members, ethics committees, fellow researchers, and some clinicians,2–4 resulting in certain studies not being approved, implemented, or completed. Such presumed burden and resulting constraints placed on pediatric palliative care research could slow advancements in this field.5 Not pursuing important research questions because of constraints could be a disservice to seriously ill children and their families. A method to sensitively assess burdens and benefits of child and family participation in pediatric palliative care studies could yield information to address concerns of reviewers, regulatory bodies, and clinicians, and new information that could guide future research.

At present, there is no established methodology to solicit from participants their possible or actual benefit or burden from participating in pediatric palliative care research although such a methodology could become a best practice standard in this field.6–8 Participation impact, when measured, appears to yield information beyond other findings in the same study, indicating that the added assessment effort can produce new and useful results. Our purpose here is to report descriptive outcomes from assessing study participation impact (burdens and benefits) from caregivers of seriously ill children after their participation in a pediatric palliative care study.

Background to the Primary Study

In the study about “being a good parent to my seriously ill child” (good parent) and caregivers (family member serving as primary caregiver) were asked to identify perceived benefits and burdens of study participation shortly after completing the study during a formal follow-up. We had previously established caregivers' definitions of being a good parent to a seriously ill child9,10 and their willingness to speak to this definition shortly after their involvement in treatment decision making on behalf of their very ill child11,12 or after their referral to a pediatric palliative care service.13,14

The primary goal of the “good parent” study, using a constructivist grounded theory methodology, was to identify internal and external factors that influence caregivers' ability to achieve their definition of being a “good parent” to their ill child. The secondary goal was to construct an integrated formal grounded theory as the basis for a future intervention to support caregiver and family well-being to diminish risks of adverse health outcomes that can be experienced by bereaved families.15,16

The primary study involved in-person consenting and had three data points (T1, T2, and T3). T1 included a face-to-face interview and measures of caregiver and family well-being and occurred within seven days of caregiver involvement in an end-of-life or treatment decision. T2 included the same interview and measures as used at T1 and was generally four to eight months after T1. T2 interviews were face to face or by telephone to allow caregivers needed flexibility. T3 was a telephone interview to assess caregivers' perceived burden and benefit of study participation and occurred one to several days after T2. The T3 telephone interviews involved only the interviewer and the caregiver. Field notes were completed after the interview.

Study Methodology

Sample

Eligible participants were English-speaking caregivers 18 years of age and older who were involved in an end-of-life decision for their child with incurable cancer or a palliative treatment decision (e.g., tracheostomy placement or resuscitation preferences) for their ill child in the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU). Exclusion criteria were caregivers considering an end-of-life decision following a child's suicide attempt or caregivers of a child who had experienced a nonaccidental trauma.

Settings

The pediatric oncology clinic and inpatient unit and the PICU at each of the two academic medical centers were the study sites. Both institutional review boards approved the study according to federal guidelines (Children's National Hospital, Pro00005750, University of Maryland, Baltimore, HP-00077824). Six study team members trained to initiate the consent process.

Design

Caregivers were reminded by the interviewer at the conclusion of T2 about the T3 contact, their agreement to receive that contact, and their preferred contact number were confirmed. The interviewer next verbally shared the three questions to be asked at T3 to allow time for the participants to reflect on the questions and purpose of the T3 contact. No caregiver at T2 declined the T3 contact. Contacting the participant to schedule the T3 interview occurred within 72 hours after T2 by telephone, text messaging, or e-mail by a female nurse study team member (C.R.) with 15 years' experience as an oncology nurse and who has certification in palliative care and study-specific training for interviewing. She was not familiar with the caregivers and/or involved in other aspects of the study. The T3 study team member was aware of which group the participant was in and whether their child had died but did not know the interview content from T1 and T2. A maximum of four attempts were made to contact caregivers for the T3 interview. Most participants (70%) were scheduled before the third attempt. The fourth attempt included a message of appreciation for the caregiver's study participation and a statement indicating that this was the final contact from the study team.

Method

The three open-ended interview items posed at T3 were previously assessed for their acceptability to caregivers who participated in a pediatric palliative care study (Insert 1).11,17 T3 was conducted for all but two interviews by the study team member assigned solely to this role. T3 interviews ranged from 10 to 30 minutes. All 37 T3 participants responded to all 3 interview questions resulting in no missing data.

Analysis

Demographic and clinical variables were analyzed using descriptive statistics (Table 1). Interview data were analyzed using descriptive content analysis.18 The unit of analysis was the phrase and the unit of response was all statements made to each specific interview question within and across interviews. Three team members jointly created the study coding dictionary from study data and using a consensus coding approach coded all T3 interviews, refining the coding dictionary concurrently. The same team members jointly examined the first-level codes for conceptual overlap and for any pattern of frequent co-occurrence. As a result, 28 first-level codes were merged into 5 themes for interview question 1, 2 themes for question 2, and 2 themes for question 3. Each code was used to induce the conceptual definition for each theme. Frequencies of the theme per caregiver group and for the total sample were calculated and confirmed independently by five other study team members. No software program was used to manage the data. The Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) were used to guide reporting the qualitative results that follow.

Table 1.

Major Themes by Interview Question, Their Definitions and Frequencies (n = 37)

| Theme | Definition | Number of caregivers reporting the theme, n (%) |

Total number of times the theme was reported, n (%) |

Exemplar quote | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PICU, n (%) | Oncology, n (%) | PICU, n (%) | Oncology, n (%) | |||

| Question 1: “What was good about participating in the Study?” | ||||||

| Hoping to help others | Caregivers shared their experiences and reflections from a desire to benefit caregivers of similarly ill children and a few from wanting to additionally help health care professionals to work more effectively with caregivers | 22 (59.5) | 28/99 (28.3) | “Something that's for the greater good … data to use for the next family going through the process” “Hoping that what I went through may be able to help others.” |

||

| 10 (45.4) | 12 (54.5) | 12 (42.8) | 16 (57.2) | |||

| Speaking about what is hard is important | Benefits of involvement in the study reported by caregivers included helping them to clarify their feelings related to the illness experience as well as enabling them to see that they and their experiences matter to others and that they, as caregivers, had taken good actions | 17 (45.9) | 33/99 (33.3) | “It was important to me that I mattered in this experience—and that my child mattered. It was important to have a voice” “It's good to speak the truth—very difficult, but good to talk about what was so hard.” |

||

| 10 (58.8) | 7 (41.2) | 12 (36.4) | 21 (63.6) | |||

| Reflecting on being a good parent altered my thinking and my behavior | Being in the study allowed an opportunity to think back on actions and decisions made to that point and to make a conscious choice to redirect actions | 15 (40.5) | 28/99 (28.38) | “Opening an opportunity for self-reflection. I found it helpful thinking personally and objective” “I think hearing an open question that allowed me to make a definition of being a good parent and that got me thinking about being a good parent to her.” |

||

| 3 (20.) | 12 (80.) | 6 (21.4) | 22 (78.6) | |||

| Confronting the harsh reality | Being in the study helped the caregiver to realize the graveness of the ill child's clinical situation and the caregiver's inability to change it, thus releasing the caregiver from such efforts and to focus instead on the child's quality of life | 5 (13.5) | 7/99 (7.1) | “Participating was acknowledging what everyone else was already accepting” “I can't do anything about her condition, but I can love her.” |

||

| 2 (40.) | 3 (60.) | 2 (28.6) | 5 (71.4) | |||

| Understanding my perspectives and those of significant others | Study participation helped to make clear/known the views and different emotions each caregiver and partner was experiencing following the child's death | 2 (5.4) | 3/99 (3.0) | “We heal differently” “The study alters your perspective and the way you live and how you look at things.” |

||

| 0 (0) | 2 (100) | 0 (0) | 3 (100) | |||

| Question 2: “What was bad or uncomfortable about participating in the study?” | ||||||

| Being in the study was sometimes hard but not bad | Caregivers described participation as important, not harmful or difficult, but for a few, uncomfortable as memories could be evoked. | 28 (75.7) | 35/40 (87.5) | “The follow-up interview shoots you right back there. We saw how much things had changed for us for the better, but it was still hard to talk about” “It was a little painful—the first round of questions because our son was very bad at that time—but not bad or difficult.” |

||

| 17 (60.7) | 11 (39.3) | 20 (57.1) | 15 (42.9) | |||

| Disliking aspects of study design | Caregivers indicated that timing of the first interview was challenging for some, and for a few, one questionnaire was challenging. | 4 (10.8) | 5/40 (12.5) | “I did not like multiple choice questions…many were similar, so it was hard to prioritize.” “Prioritizing those answers was hard, especially since it all changed depending on the situation and your state of mind.” |

||

| 1 (25.) | 3 (75.) | 1 (20.) | 4 (80.) | |||

| Question 3: “Anything else you want the Study Team to know?” | ||||||

| Wanting the health care team to recommend the family seek psychosocial support | Caregivers recommend that the treating team inform parents going through a child's illness of the importance of taking care of self and family relationships—in part through self-reflection, and knowing where to find an expert to speak with about emotional needs | 20 (54.1) | 29 (74.4) | “When you go through this process bookend to bookend, you are laid bare to the universe—personally and in your relationships. It alters your perspective and the way you live and how you look at things” “I think that the Study Team should learn that it's good for someone to always be there with the parent going through the difficult process with their child |

||

| 7 (35) | 13 (65) | 10 (34.5) | 19 (65.5) | |||

| Liking study design and methods | Caregivers found participation to be timely, thoughtfully approached, and beneficial | 9 (24.3) | 10/39 (25.6) | “The timing is spot on that you catch parents in the throes of making tough decisions and then later down the road” “In the time between the first and second interviews my child passed away. The follow-up was important to me and made me feel like I mattered.” |

||

| 7 (77.8) | 2 (22.2) | 7 (70.) | 3 (30.) | |||

PICU, pediatric intensive care unit.

Insert 1.

Interview Questions to Assess Benefit and Burden of Study Participation as Posed at T3

| Please share with me what was good about participating in this study. |

| Please share with me what was bad about participating in this study. (Planned subsequent prompt to be ‘what may have made you uncomfortable?’ if participant asked about the meaning of the interview question.) |

| Please share with me what else you would like the study team to learn from your experiences. |

Results

Sample

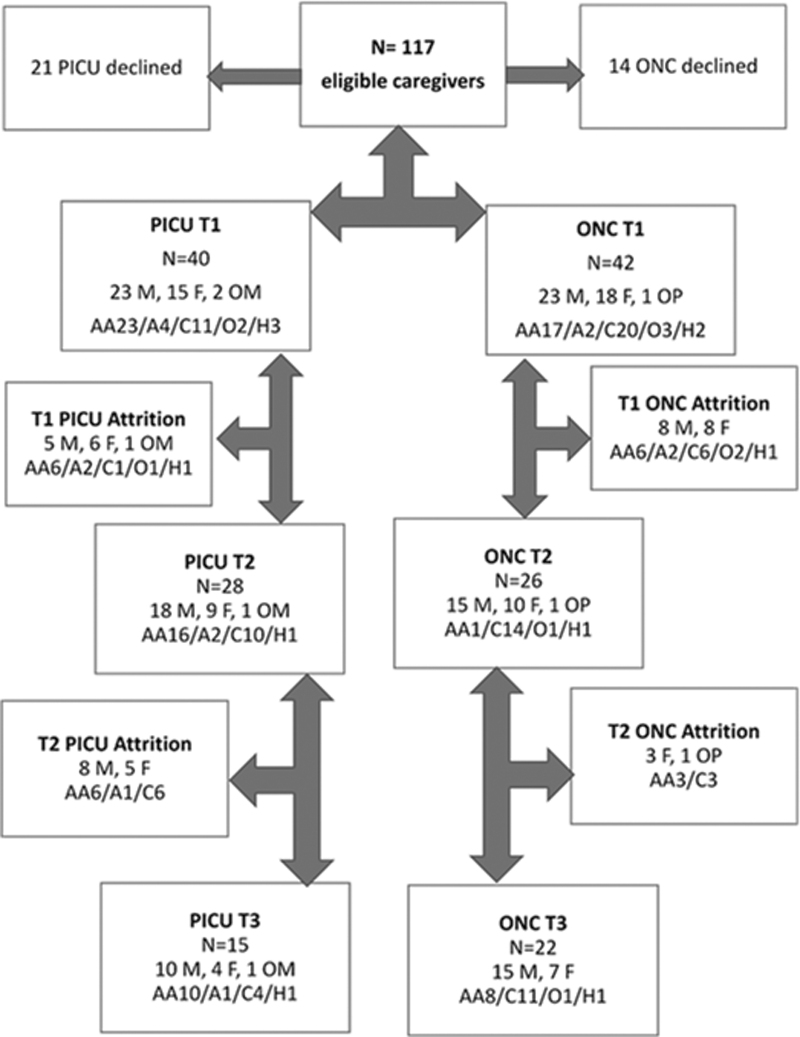

Thirty-seven caregivers, including 5 couples (3 in oncology, 2 in the PICU), of 16 male and 16 female children completed T3; 25 (67.6%) were mothers, 11 (29.7%) were fathers, and 1 (2.7%) was a grandmother. Eighteen caregivers (48.6%) were African American, 17 (45.9%) were Caucasian, 1 (2.9%) was Asian, and 1 (2.9%) identified as other. Most (n = 28, 75.8%) were married (Fig. 1). Of the 15 PICU caregivers, the majority were African American (n = 10, 66.7%); of the 22 oncology caregivers, half were Caucasian (n = 11, 50%) (Fig. 1). The diagnostic categories represented by the children of the participating caregivers in the PICU were rare congenital disorders (i.e., Aicardi syndrome, Pierre Robin syndrome, juvenile Huntington's disease, and Zellweger syndrome) (n = 8), prematurity and organ complications (n = 3), congenital heart disease (n = 2), and other (n = 2). At the time of T3, all but one child with incurable cancer had died four to five months previously and all but three children from the PICU sample were living with ongoing caregiving needs managed by their family. The average time between the T1 and T3 interviews for the oncology sample was 5.2 months and for the PICU caregiver sample was 7.8 months.

FIG. 1.

Screening, enrollment, and attrition from the primary study to T3. A, Asian; AA, African American; C, Caucasian; F, Father; H, Hispanic; M, Mother; O, other; OM/OP, other maternal/other paternal.

Themes

Interview question 1: Please share with me what was good about participating in this study

The most frequently reported theme to question 1 and reported at similar rates by caregivers from both groups was “Hoping to help others.” Despite experiencing the death of their child or the decline in their child's health status, these 22 caregivers were clear that they wanted to help other caregivers feel supported in their treatment decision making for their ill child (Oncology Mother 106: “The good thing is that I hope this will help other caregivers so what they go through will be easier for them”; PICU Father 11: “Just that I hope whatever we said will be useful to other families going through similar circumstances. I don't think I actually gained much from the study, but if it will help others via the research that is good and this is enough for me.”). Several caregivers also communicated a desire to offer guidance for professionals who interact with such caregivers (PICU Mother 002: “Sometimes doctors and nurses don't really know how the person receiving the information was feeling, like how they were in that moment. All parents are not the same. This was my main motivation for consenting to do the study.”; Oncology Mother 127: “…help doctors how to handle patients and families in desperate situations, to be conscious of how to reach out to them and help.”) (Table 1).

The second frequently reported theme by caregivers (n = 17, 46%) was “Speaking about what is hard is important.” These 17 family caregivers emphasized 33 times (reported nearly 2 times more frequently by the oncology caregivers) that there is personal benefit in speaking about “being a good parent” during difficult and sad times. The personal benefits involved clarifying feelings (Oncology Father 100: “It's good to speak the truth—very difficult but good to talk about what was so hard.” Oncology Mother 102: “I think I was able to clear my mind—get my thoughts out.”), reflecting on past actions and experiencing a surprising awareness of having made reasonable decisions and taken positive actions for this ill child and other family members (Table 1).

The third frequently reported theme by caregivers (n = 15, 40.5%) was “Reflecting on being a good parent altered my thinking.” These caregivers, referring to this theme 28 times, indicated that this question allowed them an opportunity to recall their efforts and to see which ones were based on their needs versus their child's needs (PICU Mother 010: “the questions that they asked made me think about things in a different way, especially about making family decisions that I hadn't given much thought to…”), enabling self-redirection to consider subsequent decisions in light of their ill child's needs (Mother Oncology 104; “it allowed me to reflect on what I was doing and adjust my behavior to move forward.”; Oncology Father 105: “It allowed me to take a step back and process my thoughts and emotions—how did I want to tackle what was going on. It helped to put things into perspective to try to take a simple approach …that would work for all of us.”) This theme was reported proportionately by more caregivers in the oncology group (Table 1).

The remaining two themes, “Confronting the harsh reality” and “Understanding my perspectives and those of significant others,” represent fewer caregivers (n = 5, 13.5% and n = 2, 5.4%, respectively). The first theme represented caregivers' views that speaking about the sadness of their child's illness situation and their inability to improve it helped them to say aloud what others likely already knew to be true, allowing them to focus more time and effort on “being a good parent” to their ill child for the remaining time (PICU Father 54: “I think it helped me realize, in many ways, about being a good parent in a situation in which you may feel you're not because you have no control.”; Oncology Father 100: “I couldn't do what I wanted—make my son better. He was in hospice 6 weeks so I couldn't stop to deal with feelings of guilt and shame, so it helped to see the good I was doing for the other kids. Speaking helped.”). The final theme was reported by caregivers who described the benefit to them of being interviewed in the presence of their significant other, at their request. In these instances, parents were able to listen to their significant other's responses to the interview questions, which subsequently helped them to understand how their significant other experienced grief over time (PICU Mother 53: “By answering the questions in the survey, we are sharing our feelings and thoughts. We had no one else to share these with.” Oncology Mother 102: “It was good to hear what my husband was thinking—we are grieving very differently, and this helped.”) (Table 1).

Interview question 2: Please share with me what was bad about participating in this study

The dominant theme to this question was “Being in the study was sometimes hard but not bad,” offered by 28 (75.7%) caregivers at a higher frequency (35 times) than all other themes. Twenty of the 28 (89.3%) stated simply “nothing was bad” about being in the study. Several caregivers spoke to sad memories being evoked by their interviews but indicated that they had anticipated this and did not find participation to be harmful or difficult [PICU Mother 020: “It was difficult, me having to speak, grieve and inhale my difficult reality. I was bound and committed to it, but, as a human being, there are numbing-coping mechanisms so heavy and taxing to talk about my situation, it makes you tired. You feel better after…”; PICU Father 011: “it was a little painful, the first round of questions because our son was very bad at that time—but not bad or difficult. (It was) the circumstances of our child's situation which caused us to be approached was a little painful.”; PICU Mother 002: “Nothing was uncomfortable. I relived some things I experienced with my son but that was ok.”] None recommended not participating. The second theme to this question represented only four caregivers (10.8%) who indicated dislike for one quantitative questionnaire in the primary study (Table 1).

Interview question 3: Please share with me what else you would like the study team to learn from your experiences

Two themes were identified in response to question 3, “Wanting the health care team to recommend the family seek psychosocial support” (n = 20, 54.1%) and “Liking study design and methods” (n = 9, 24.3%). The dominant theme focused on the caregivers' likely need for professional psychosocial support while experiencing their child's illness and was predominately reported by caregivers in the oncology group. This need was linked to the desire to have health care professionals emphasize to caregivers the importance of finding ongoing support for themselves (PICU Father 50: “I think the team should learn that it's good for someone to always be there with the parent going through the difficult process with their child.”; Oncology Father 116: “I think the team should encourage parents to take care of themselves because they are at risk.”) The second theme represented the spontaneous participant reports relating their positive regard for the study methods, including the timing of the interviews and the nature of the interview questions (PICU Mother 53: “Everything was perfect; good questions and perfectly said.”; PICU Father 21: “You guys hit it on the nail, from beginning to end. The questions were complete and detailed and covered everything.”) (Table 1).

Discussion

We used three interview questions to assess impact on caregivers of participating in a pediatric palliative care study in oncology and intensive care units at two academic centers. We found that all participants responded seemingly with ease to all three T3 questions resulting in no missing data. In the few previous studies that have assessed impact of caregiver study participation, methods have varied widely: mailed surveys with closed and/or open-ended questions,19–22 two to three telephone interview questions,23,24 a Facebook questionnaire,25 in-person administered questionnaires,4 and face-to-face structured or in-depth interviews.26,27 Timing of benefit and burden assessments of research participation varied (hours to 4 weeks to unknown), as did study sample size (8–178 caregivers). Like our methods, three prior studies reported participants' favorable response to limited telephone interview questions .11,19,23 Collectively, the outcomes of these diverse methods support the acceptability for up to 80% of eligible caregivers of participating in pediatric palliative research and evaluating their study experience.

In our study, the most frequently reported caregiver outcomes were benefits of study participation for themselves (i.e., reflecting favorably on positive actions taken for the ill child or other family members, being more likely to see the reality of their child's situation, and noting how their thinking and actions were altered as a result of study participation). Multiple caregivers described these benefits as not likely to have occurred without the study questions at T1 and T2 having been posed to them. Words used to describe the experience of study participation imply that in some instances, the experience was therapeutic. The study design, including the impact assessment at T3, may have provided caregivers the rare opportunity to reflect on themselves and their actions in contrast to their singular focus on their ill child. Benefits of study participation have been similarly reported by bereaved parents in other studies that used diverse methods and timing to document their reports.4,9,14,19–23

Other caregivers' reported benefits were the opportunity to contribute to the well-being of current and future caregivers of seriously ill children, indicating altruistic motivation. Examples included leaving their personal stories behind through data to help others understand and deal with similar experiences. To a lesser extent, some participants also wanted to provide guidance for clinicians interacting with caregivers of seriously ill children (i.e., urging caregivers to be more mindful of seeking psychosocial support for themselves). Altruistic motivation for research participation is documented across vulnerable populations, such as people living with HIV28 or advanced cancer29; survivors of injury30 or sexual assault31; family caregivers of seriously ill individuals1,31; and parents and children.32,33 Our findings indicate that parents of seriously ill children are motivated at least in part to participate in pediatric palliative care research to improve their lives and those of others through science. The likelihood of study participants having multiple motivations for enrolling and remaining in clinical pediatric palliative care research has been previously reported.34

Caregivers spoke to the burdens or negative aspects of study participation. Some acknowledged that the questions in the parent study could evoke sad or uncomfortable memories associated with their ill child but added that these same memories were present during many life moments, apart from the study. The risk of study burden indicates the importance of a study team being formally prepared for sensitive moments likely to occur during caregiver interviews. Four caregivers indicated timing of the initial interview was challenging as they were still absorbing the deteriorating health status of their ill child and others described dislike of a study questionnaire used at T1 and T2. Such impact feedback gives direction to more flexible design enrollment and removal of selected measures for future studies.

Although benefits were primarily reported, this finding needs to be considered in the context of the parent study refusal rate (29.9% overall; 40% in oncology, 60% in PICU) and attrition. The refusal rate may convey that some caregivers, particularly those in the PICU, were not ready for or not interested in a palliative care study. Of importance, this refusal rate also conveys that caregivers amid dealing with a seriously ill, hospitalized child are able to exercise their rights to decline study participation. Refusal rates from a previously completed good parent study involving caregivers of children with incurable cancer and a similar T1 to T3 design (21.5%)11 and a PICU study with a single data point without follow-up (19%)12 were lower than this study.

For the PICU sample, 70% of the T1 sample completed the T2 interview but only 37.5% completed the T3 interview. For the oncology sample, 61.9% completed the T2 interview and 52.4% completed the T3 interview. Attrition between T2 and T3 is challenging to explain as caregivers at T2 were reminded of the T3 contact, confirmed their preferred contact information, and were contacted within three days after T2. Four oncology families (15.4%) and 12 PICU families (42.9%) could not be reached (1 PICU family cancelled the scheduled T3 interview because of an emergency). Caring for a seriously ill child at home could contribute to the higher attrition in the PICU caregiver group. Attrition between data points and our not being able to explain the attrition supports embedding the impact assessment of benefits and burdens into each study data point rather than an impact data point that only occurs at the conclusion of a study. Previously reported caregiver and adult patient attrition rates in palliative care studies have ranged from 0% to 96%35–38 and the rate from a previous good parent study was 25.8%.11 These rates indicate the need to carefully tailor timing of measuring impact to match differences in clinical contexts. Planning study resources to include more than one team member assigned to assessing impact may also be of benefit. Caregiver attrition in pediatric palliative research has not been the focus of a systematic review or other evidence synthesis. The report on attrition by the MORECare guideline group concluded that palliative care trials have higher rates of attrition than studies with nonpalliative care participants and that reasons for attrition are typically not documented or reported.36,39

Although our sample is small at T3, our study findings including our attrition rates in both groups suggest that assessing the impact of participation in pediatric palliative care research may be most informative if carried out during a study, such as after each data point rather than only after the final data point. Using a low demand, standard assessment method such as these three interview questions applied systematically would allow outcomes from diverse studies, samples, and designs to be compared. Differences and similarities in the outcomes would be related to the study itself and not to the impact assessment method if highly similar impact methods were used across studies. Certain settings may be more hesitant than others to support pediatric palliative care; in such instances, having a low demand impact assessment embedded in a study may help ease such concerns. Our theme findings may be useful to address presumed burden by review boards or individuals and may be used during consenting processes to better inform eligible participants about benefits and burdens experienced by other participants in pediatric palliative care studies.

Conclusion

The three-question interview format used here to assess benefits and burdens of caregiver participation in a pediatric palliative care study was completed without any missing responses. Benefits of study participation were most frequently reported by the study participants and importantly, the most frequently reported theme was that no burdens secondary to study participation were experienced. Having a standard approach to measure caregiver benefits and burdens of participating in pediatric palliative care studies is merited and would yield important information for clinicians, researchers, reviewers, and future participants.

Funding Information

NIH NINR R01NR015831 (Pamela S. Hinds, PI). How Parent Constructs Affect Parent and Family Well-Being after a Child's Death.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Supplementary Material

T3 JPM Hinds COREQ_Checklist

References

- 1. Weaver, MS, Mooney-Doyle K, Kelly KP, et al. : The benefits and burdens of pediatric palliative care and end-of-life research: A systematic review. J Palliat Med 2019;22:915–926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dixon-Woods M, Young B, Ross E: Researching chronic childhood illness: The example of childhood cancer. Chronic Illn 2006;2:165–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rapoport A: Addressing ethical concerns regarding pediatric palliative care research. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2009;163:688–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wiener L, Battles H, Zadeh S, Pao M: Is participating in psychological research a benefit, burden, or both for medically ill youth and their caregivers? IRB 2015;37:1–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Feudtner C, Rosenberg AR, Boss RD, et al. : Challenges and priorities for pediatric palliative care research in the U.S. and similar practice settings: Report from a pediatric palliative care research network workshop. J Pain Manage 2019;58:909–917.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Currier JM, Hermes S, Phipps S: Children's response to serious illness: Perceptions of benefit and burden in a pediatric cancer population. J Pediatr Psychol 2009;34:1129–1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Emanuel EJ, Fairclough DL, Wolfe P, Emanuel LL: Talking with terminally ill patients and their caregivers about death, dying, and bereavement: Is it stressful? Is it helpful? Arch Intern Med 2004;164:1999–2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Weaver MS, Bell CJ, Diver JL, et al. : Surprised by benefit in pediatric palliative care research. Cancer Nurs 2018;41:86–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hinds PS, Oakes LL, Hicks J, et al. : “Trying to be a good parent” as defined by interviews with parents who made end-of-life decisions for their children. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:5979–5985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Maurer SH, Hinds PS, Spunt SL, et al. : Decision making by parents of children with incurable cancer who opt for enrollment on a Phase I trial compared with choosing a do not resuscitate/terminal care option. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:3292–3298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hinds PS, Oakes LL, Hicks J, et al. : Parent-clinician communication intervention during end-of-life decision making for children with incurable cancer. J Palliat Med 2012;15:916–922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. October TW, Fisher KR, Feudtner C, Hinds PS: The parent perspective: “Being a good parent” when making critical decisions in the PICU. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2014;15:291–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hill DL, Miller V, Walter JK, et al. : Regoaling: A conceptual model of how parents of children with serious illness change medical care goals. BMC Palliat Care 2014;13:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Feudtner C, Walter JK, Faerber JA, et al. : Good Parent beliefs of parents of seriously ill children. JAMA Pediatr 2015;169: 39–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cote-Arsenault D, Denney-Loelsch EM, McCoy TP, Kavanaugh L: African American and Latino bereaved parent health outcomes after receiving perinatal palliative care: A comparative mixed methods case study. Appl Nurs Res 2019;50:151200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. October T, Dryden-Palmer K, Copnell B, Meert KL: Caring for parents after the death of a child. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2018;19:S61–S68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Baker JN, Windham JA, Hinds PS, et al. : Bereaved parents' intentions and suggestions about research autopsies in children with lethal brain tumors. J Pediatr 2013;163:581–586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Krippendorff K: Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology, 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Donovan LA, Wakefield CE, Russell V, et al. : Brief report: Bereaved parents informing research design: The place of a pilot study. Death Stud 2019;43:62–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kreicbergs U, Valdimarsdottir U, Steineck G, Henter JI: A population-based nationwide study of parents' perceptions of a questionnaire on their child's death due to cancer. Lancet 2000;364:787–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Scott DA, Valery PC, Boyle FM, Bain CJ: Does research into sensitive areas do harm? Experiences of research participation after a child's diagnosis with Ewing's sarcoma. Med J Aust 2002;177:507–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dyregrov K: Bereaved parents' experience of research participation. Soc Sci Med 2004;58:391–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Butler AE, Hall H, Copnell B: Bereaved parents' experiences of research participation. BMC Palliat Care 2018;17:122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hopper A, Crane S: Evaluation of the burdens and benefits of participation in research by parents of children with life-limiting illnesses. Nurs Res 2019;27:8–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tager J, Battles H, Bedoya SZ, et al. : Participation in online research examining end-of-life experiences: Is it beneficial, burdensome, or both for parents bereaved by childhood cancer? J Pediatr Oncol Nurs 2019;36:170–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hynson JL, Aroni R, Bauld C, Sawyer SM: Research with bereaved parents: A question of how not why. Palliat Med 2006;20:805–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Allen KA, Kelley TF: The risks and benefits of conducting sensitive research to understand parental experiences of caring for infants with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. J Neurosci Nurs 2016;48:151–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Perry KE, Dube K, Concha-Garcia S, et al. : “my death will not be in vain: Testimonials from last gift rapid research autopsy study participants living with HIV at the end of life. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2020;36:1071–1082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ulrich CM, Knafl KA, Ratcliffe SJ, et al. : Developing a model of the benefits and burdens of research participation in cancer clinical trials. AJOB Prim Res 2012;3:10–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Irani E, Richmond TS: Reasons for and reservations about research participation in acutely injured adults. J Nurs Scholarsh 2015;47:161–169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Campbell R, Adams AE: Why do rape survivors volunteer for face-to-face interviews? A meta-study of victims' reasons for and concerns about research participation. J Interpers Violence 2008;24:395–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wendler D, Glantz L: A standard for assessing the risks of pediatric research: Pro and con. J Pediatr 2007;150:579–582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wendler D, Abdoler E, Wiener L, Grady C: Views of adolescents and parents on pediatric research without the potential for clinical benefit. Pediatrics 2012;130:692–699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jansen LA: The ethics of ALTRUISM in clinical research. Hastings Cent Rep 2009;39:26–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Aoun S, Slatyer S, Deas K, Nekolaichuk C: Family caregiver participation in palliative care research: Challenging the myth. J Pain Symptom Manage 2017;53:851–861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Higginson IJ, Evans CJ, Grande G, et al. : Evaluating complex interventions in End of Life Care: The MORECare statement on good practice generated by a synthesis of transparent expert consultations and systematic reviews. BMC Med 2013;11:111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hui D, Glitza I, Chisholm G, et al. : Attrition rates, reasons and predictive factors in supportive and palliative oncology clinical trials. Cancer 2013;119:1098–1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hudson P: The experience of research participation for family caregivers of palliative Care cancer patients. Int J Palliat Nurs 2003;9:120–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Oriani A, Dunleavy L, Sharples P, et al. : Are the MORECare guidelines on reporting of attrition in palliative care research populations appropriate? A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Palliat Care 2020;19:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]