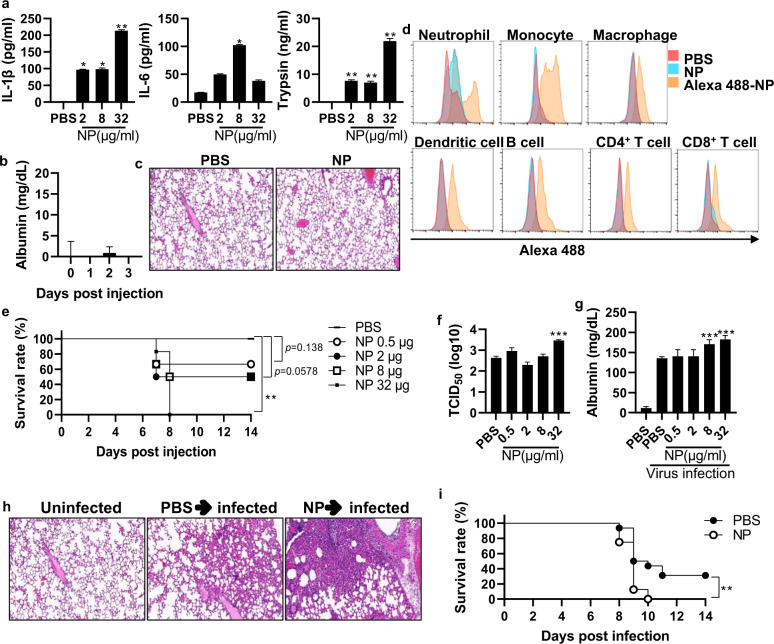

Fig. 5. NP contributes to an increased viral titer and influenza pathogenicity in vivo.

a Mice (n = 5) were treated intranasally with rNP (2–32 μg/mouse). After 6 h, the levels of IL-1β, IL-6, and trypsin in the BALF were measured by ELISA. b Mice (n = 5) were treated intranasally with rNP (32 μg/mouse), and albumin was measured in the BALF daily for three days. c Mice were treated intranasally with rNP (32 μg/mouse), and the histology of lung tissue was assessed after hematoxylin-eosin (H&E) staining. d Isolated total lung cells were incubated with Alexa 488-labeled rNP (100 μg/ml) for 15 min, and NP-bound cells were evaluated by flow cytometry. e Mice (n = 6) were treated intranasally with NP (2–32 μg/ml) and subsequently infected with the PR8 virus (32 PFU) on Day 3. The survival rate was monitored for two weeks. f–h At five days post-infection, the viral load and the level of albumin in the BALF were determined. Histological analysis of lung tissue was performed after H&E staining. i Mice (n = 16) were treated intranasally with NP (2–32 μg/ml) three days prior to PR8 viral infection (32 PFU). Upon infection, the survival rate was monitored for two weeks. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05