(

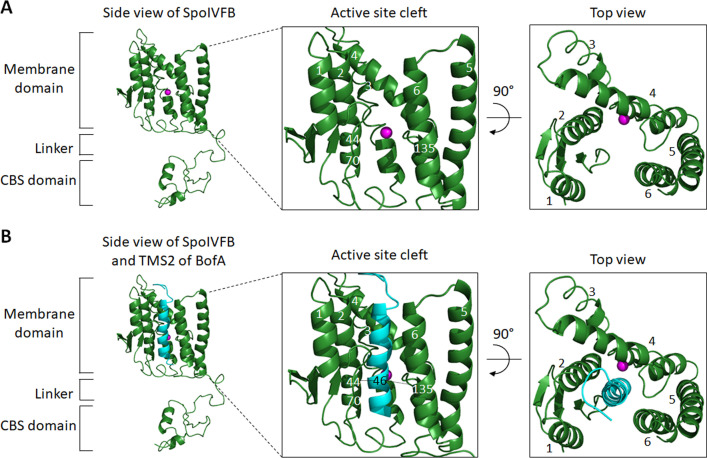

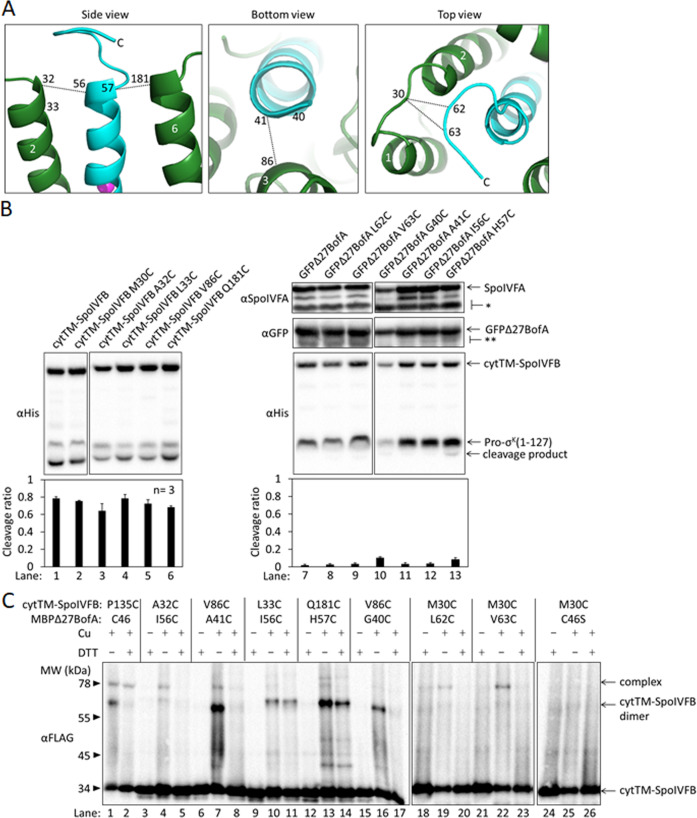

A) Enlarged view of the model of SpoIVFB and BofA TMS2 shown in

Figure 4—figure supplement 1B, which is based in part on disulfide cross-linked complexes shown in (

C). At

Left, the side view of SpoIVFB TMS2 and TMS6 (green) is shown with the zinc ion (magenta) involved in catalysis and BofA TMS2 (cyan). This view depicts experimentally observed cross-links (dashed lines) between BofA I56C and SpoIVFB A32C, and between BofA H57C and SpoIVFB Q181C. In the bottom view (

Center), BofA TMS2 is shown with SpoIVFB TMS3. The dashed line indicates a cross-link between BofA A41C and SpoIVFB V86C that was observed. At

Right, the top view of the model is shown. The dashed lines indicate observed cross-links between SpoIVFB residue M30C (located in the loop connecting TMS1 and TMS2) and BofA L62C and V63C (in a loop near the C-terminal end of TMS2). (

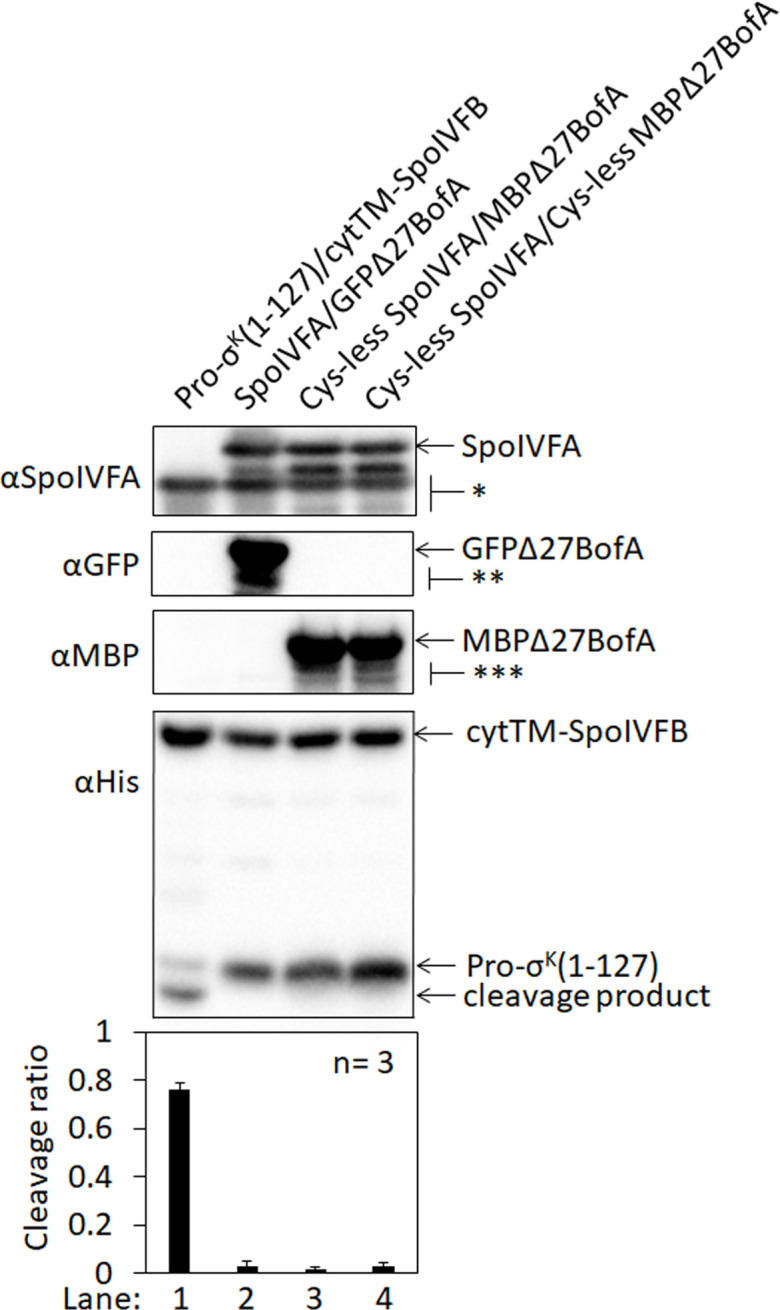

B) Cleavage assays examining the effects of Cys substitutions for residues of interest in cytTM-SpoIVFB or GFPΔ27BofA. BofA TMS2 was modeled in the SpoIVFB active site cleft based on our initial cross-linking results (

Figure 4). The initial model predicted proximity between residues at or near the ends of BofA TMS2 and residues of SpoIVFB, thus identifying residues of interest for cross-linking experiments. First, we examined the effects of Cys substitutions for the residues of interest using cleavage assays. pET Duet plasmids were used to produce Pro-σ

K(1–127) in combination with cytTM-SpoIVFB from pYZ2 as a control (lane 1) or with the indicated Cys-substituted cytTM-SpoIVFB from pSO141 or pSO256-pSO259 in

E. coli (

Left). pET Quartet plasmids were used to produce Pro-σ

K(1–127), cytTM-SpoIVFB, and SpoIVFA in combination with GFPΔ27BofA from pSO40 as a control (lane 7) or with the indicated Cys-substituted GFPΔ27BofA from pSO142, pSO143, or pSO260-pSO263 in

Escherichia coli (

Right). Samples collected after 2 hr of IPTG induction were subjected to immunoblot analysis, and the graph shows quantification of the cleavage ratio, as explained in the

Figure 1B legend. Since cytTM-SpoIVFB with Cys substitutions for residues of interest cleaved Pro-σ

K(1–127) (lanes 2–6), we included the inactivating E44Q substitution in the single-Cys cytTM-SpoIVFB variants created for cross-linking. GFPΔ27BofA with Cys substitutions for residues of interest inhibited Pro-σ

K(1–127) cleavage by cytTM-SpoIVFB, although the G40C and H57C substitutions caused partial loss of inhibition, and the G40C substitution resulted in less accumulation of all four proteins (lanes 8–13). Ala substitutions at these positions had similar effects (

Figure 2, lanes 2 and 15). (

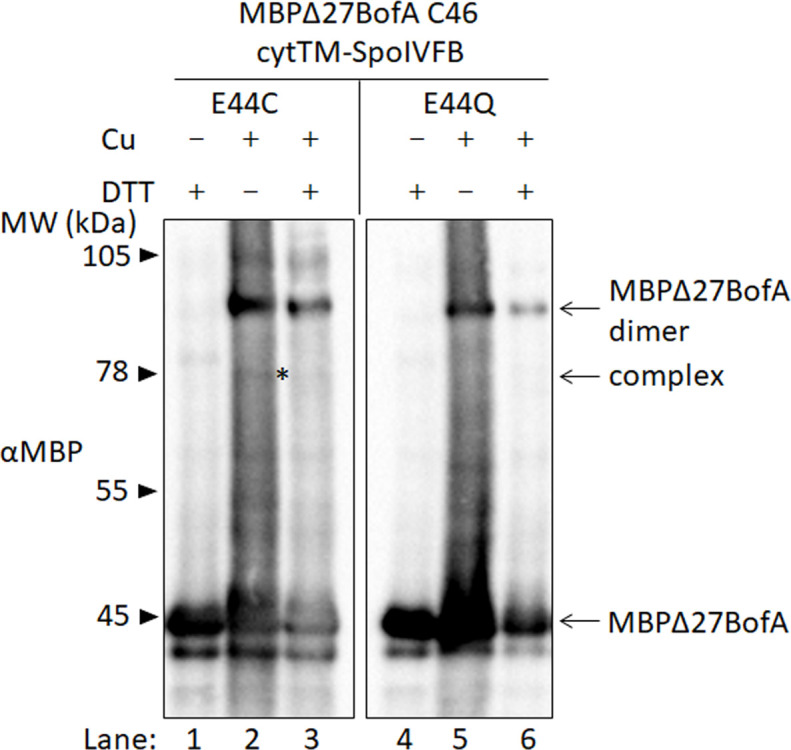

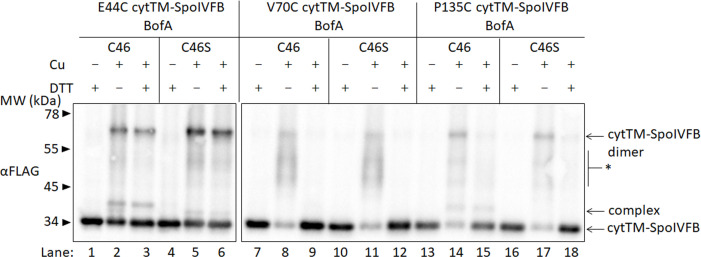

C) Disulfide cross-linking of single-Cys cytTM-SpoIVFB variants to single-Cys MBPΔ27BofA variants. pET Quartet plasmids (pSO93 as a positive control in lanes 1 and 2, pSO147, pSO148, and pSO186–pSO190) were used to produce single-Cys cytTM-SpoIVFB E44Q variants in combination with single-Cys MBPΔ27BofA variants or Cys-less MBPΔ27BofA from pSO144 as a negative control, and Cys-less variants of SpoIVFA and Pro-σ

K(1–127) in

E. coli. Samples collected after 2 hr of IPTG induction were treated and subjected to immunoblot analysis as explained in the

Figure 4A legend. A representative result from two biological replicates is shown. In agreement with the model shown in (

A), I56C and H57C MBPΔ27BofA variants formed a cross-linked complex with A32C and Q181C cytTM-SpoIVFB variants, respectively (lanes 4 and 13). The I56C MBPΔ27BofA variant formed very little complex with the L33C cytTM-SpoIVFB variant (lane 10), suggesting that a preferred orientation of BofA TMS2 places I56C farther from L33C than from A32C in TMS2 of SpoIVFB. Similarly, comparison of complex formation by G40C and A41C MBPΔ27BofA variants with the V86C cytTM-SpoIVFB variant (lanes 7 and 16) suggested that a preferred orientation of BofA TMS2 places G40C farther than A41C from V86C near the C-terminal end of SpoIVFB TMS3. Likewise, L62C and V63C MBPΔ27BofA variants formed a cross-linked complex with the M30C cytTM-SpoIVFB variant (lanes 19 and 22), suggesting a loop near the C-terminal end of BofA TMS2 is in proximity to a loop between SpoIVFB TMS1 and TMS2.