Abstract

Objectives

There are sex differences in distribution of fat and in the prevalence of overweight and obesity. We therefore sought to explore sex differences in the prevalence of adiposity-metabolic health phenotypes, in anthropometric and cardio-metabolic parameters, and in the relationship between body mass index (BMI) categories and metabolic health.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional study carried out between January 2018 and June 2019, of a nationally representative sample of the Maltese Caucasian population aged 41 ± 5 years. Metabolic health was defined as presence of ≤ 1 parameter of the metabolic syndrome as defined by the National Cholesterol Education Program-Adult Treatment Panel III criteria.

Results

Males exhibited the unhealthy metabolic phenotype more frequently than women (41.3% vs 27.8%). In total, 10.3% of normal weight men and 6.3% of normal weight women were metabolically unhealthy. Males had a higher median BMI, but a lower proportion of males exhibited an abnormally high waist circumference as compared with females. A significant difference in sex distribution was noted for each body composition phenotype.

Conclusion

In a contemporary sample of middle-aged individuals, males were more metabolically unhealthy and more insulin resistant than their female counterparts in spite of exhibiting an abnormal waist circumference less frequently and having similar waist index. This suggests that the currently used cut-offs for normal waist circumference should be revised downwards in men. Since even normal weight men were more often metabolically unhealthy than normal weight women, BMI cut-offs may also need to be lowered in men.

Keywords: Gender, Adiposity, Metabolic health, Metabolic syndrome, Body fat distribution, Body mass index, Body size phenotypes

Résumé

Objectifs

Il existe des différences entre les sexes dans la distribution de la graisse et dans la prévalence du surpoids et de l’obésité. Nous avons donc cherché à explorer les différences entre les sexes dans la prévalence des phénotypes d’adiposité et de santé métabolique, dans les paramètres anthropométriques et cardio-métaboliques et dans la relation entre les catégories d’indice de masse corporelle (IMC) et la santé métabolique.

Méthodes

Nous avons mené une étude transversale entre janvier 2018 et juin 2019, auprès d’un échantillon représentatif au niveau national de la population caucasienne maltaise âgée de 41 ans (± 5 ans). La santé métabolique a été définie comme la présence de ≤ 1 paramètre du syndrome métabolique tel que défini par les critères du National Cholesterol Education Program-Adult Treatment Panel III.

Résultats

Les hommes présentaient le phénotype métabolique malsain plus fréquemment que les femmes (41,3 % c. 27,8 %). 10,3 % des hommes de poids normal et 6,3 % des femmes de poids normal étaient métaboliquement malsains. Les hommes avaient un IMC médian plus élevé, mais une proportion plus faible d’hommes présentaient un tour de taille anormalement élevé par rapport aux femmes. Une différence significative dans la distribution des sexes a été notée pour chaque phénotype de composition corporelle.

Conclusion

Dans un échantillon contemporain d’individus d’âge moyen, les hommes étaient plus malsains sur le plan métabolique et plus résistants à l’insuline que leurs homologues féminins, même s’ils présentaient moins souvent un tour de taille anormal et avaient un indice de taille similaire. Cela suggère que les seuils actuellement utilisés pour un tour de taille normal devraient être revus à la baisse chez les hommes. Puisque même les hommes de poids normal étaient plus souvent métaboliquement malsains que les femmes de poids normal, les seuils de l’IMC devraient peut-être aussi être revus à la baisse chez les hommes.

Mots-clés: Santé métabolique, obésité, syndrome métabolique, obésité métaboliquement saine

Introduction

Increased adiposity is well established as a cardiovascular risk factor (Dyer et al., 2004). This is largely mediated through metabolic derangements, including hyperglycaemia, dyslipidaemia, and insulin resistance/hyperinsulinaemia (Van Gaal et al., 2006). These metabolic derangements increase cardiovascular risk by inducing a sustained subclinical pro-inflammatory state, endothelial dysfunction, and accelerated atherosclerosis. Despite the close association of increased adiposity with metabolic abnormalities, there is considerable variability in the metabolic health status of individuals within each of the body mass index (BMI) categories of normal weight, overweight, or obese. For example, some normal weight patients exhibit metabolic abnormalities while some overweight and obese individuals do not. This has led to the concept of metabolic health, which can be used in addition to the BMI in order to better characterize patients.

Visceral adiposity is known to be more strongly associated with cardiovascular risk than subcutaneous adiposity (Lapidus et al., 1984). Waist circumference is widely regarded as a marker of visceral adiposity and is linked with increased cardiovascular disease (Yusuf et al., 2004). There are significant sex differences in the prevalence of overweight and obesity and in the distribution of fat. We therefore sought to explore sex differences in the prevalence of adiposity-metabolic health phenotypes in a nationally representative sample of middle-aged subjects of Maltese-Caucasian ethnicity. We also sought to investigate sex differences in anthropometric measurements and cardio-metabolic parameters and the relationship between BMI categories and metabolic health.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional study carried out between January 2018 and June 2019, of a nationally representative sample of the Maltese-Caucasian non-institutionalized population aged 41 ± 5 years using convenience sampling similar to that used in the ABCD study (Buscemi et al., 2017). Exclusion criteria included pregnancy, type 1 diabetes, known underlying genetic or endocrine causes of overweight or underweight (apart from controlled thyroid disorders), individuals with a terminal illness or active malignancy, and inability to provide voluntary informed consent.

Level of education was stratified as primary, secondary, or tertiary education according to the highest completed level. Workers in the first four categories of the 1994 Spanish National Classification of Occupations were classified as white-collar workers whereas those falling in the last five categories were grouped as blue-collar workers, as previously described by Sánchez-Chaparro et al. (2008). Smoking status, alcohol consumption, and physical activity were classified as in the National Health and Nutritional Examination Survey (Wildman et al., 2008). Blood pressure was measured according to the European Society of Hypertension Guidelines (Williams et al., 2018).

Anthropometric measurements were recorded with the participants dressed in light clothing and without shoes, using validated equipment which was calibrated in accordance with WHO recommendations. Body weight was measured in kilograms to the nearest 0.1 kg and height to the nearest 0.1 cm using a calibrated stadiometer. Normal weight was defined as a BMI value of < 25 kg/m2; overweight as a BMI of 25.0–29.9 kg/m2; and obesity as a BMI of ≥ 30 kg/m2. All body circumferences were measured to the nearest 0.1 cm with a non-stretchable measuring tape using standard procedure with the subjects standing upright, with shoulders and thighs relaxed, facing the investigator (Ge et al. 2014). Waist index was calculated as the waist circumference (WC) (cm) / 94 for males; and WC (cm) / 80 for females (Magri et al., 2016). The conicity index, the atherogenic index of plasma, the body adiposity index, the lipid accumulation product, and the body roundness index were calculated as previously described (Kahn 2005; Thomas et al., 2013; Parati et al., 2014; Hermans et al., 2012). Blood samples were collected after an overnight (12-h) fast for the determination of fasting plasma glucose (FPG) and other biochemical parameters. Fasting serum insulin was measured using a solid-phase sandwich enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (Diagnostic Automation, USA). The homeostasis model assessment (HOMA) was used to evaluate insulin resistance (IR) (Matthews et al., 1985). A cut-off value of < 2.5 was used to identify the metabolically healthy phenotype. This cut-off value was chosen as it has already been used in other studies (Durward et al., 2012).

Body size phenotypes were generated based on the combined consideration of each participant’s BMI category and metabolic health. Individuals were classified as being metabolically healthy if they exhibited 1 or none of the cardiometabolic abnormalities as per the definitions of National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Adult Treatment Panel III (ATP III) criteria for the metabolic syndrome (2002), as in previous studies (Lin et al., 2020; Elías-López et al., 2021). These parameters include (a) waist circumference > 102 cm in men and > 88 cm in women; (b) systolic/diastolic blood pressure ≥ 130/85 mmHg or on antihypertensive medication; (c) serum triglyceride level ≥ 1.69 mmol/L or on lipid-lowering medication; (d) HDL-C < 1.03 mmol/L in males and < 1.29 mmol/L in females or on treatment aimed to increase HDL-C; (e) fasting glucose ≥ 5.6 mmol/L or on antihyperglycemic agents. Initially for prevalence purposes overweight and obese subjects were analyzed separately, thus generating six different body composition phenotypes: metabolically healthy normal weight (MHNW); metabolically unhealthy normal weight (MUHNW); metabolically healthy overweight (MHOW); metabolically unhealthy overweight (MUHOW); metabolically healthy obese (MHO); metabolically unhealthy obese (MUHO).

Thereafter, the overweight and obese subjects were analyzed together as one entity, thus generating four body composition phenotypes: metabolically healthy normal weight (MHNW); metabolically unhealthy normal weight (MUHNW); metabolically healthy overweight or obese (MHOW/Ob); metabolically unhealthy overweight or obese (MUHOW/Ob).

Statistical analysis

A minimum sample size was calculated using the one proportion formula for cross-sectional studies. The WHO age-standardized prevalence of obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 = 28.9%) was used since at the population level, obesity is a robust predictor of cardiometabolic risk. Considering a power of 90%, precision of 0.05, significance of 0.05, and an expected response rate of 90%, a minimum sample size of n = 352 was obtained (Dhand and Khatkar 2014).

Normality of distribution of continuous data was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk and Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests. Since all continuous variables showed a skewed non-normal distribution, they are presented as medians and interquartile range and non-parametric tests were used for comparisons. To evaluate differences in quantitative variables between groups, Kruskal–Wallis ANOVA was used for comparison between three or more categories, followed by Dunn’s post hoc test for pairwise comparison between subgroups. The independent samples Mann–Whitney U test was used for comparison between two categories. Bonferroni adjustment of p-values for multiple comparisons was applied. The χ2 test was used to compare categorical variables. To identify predictors of HOMA-IR, we applied generalized linear modelling to predict HOMA-IR as the continuous response variable. Simple parameters that can be easily ascertained at the bedside were included as scale-independent variables (age, waist-hip ratio, BMI, and neck circumference). Lifestyle factors—smoking, physical activity, and alcohol consumption—were also combined into the regression model as categorical independent predictors. Generalized linear modelling specifying gamma as the distribution and Log as the link function was applied, in view of the positively skewed distributions of parameters under investigation. Multicollinearity diagnostics revealed no dependency between independent variables, with variance inflation factors < 2.5 and tolerance statistic values > 0.7, thus indicating they could be reliably used as predictors in the model.

All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS version 22. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered significant.

The study was approved by the University of Malta Research Ethics Committee (UREC MD 06/2016) of the Faculty of Medicine and Surgery and by the Information and Data Protection Commissioner. All subjects gave their written informed consent to participate in the study.

Results

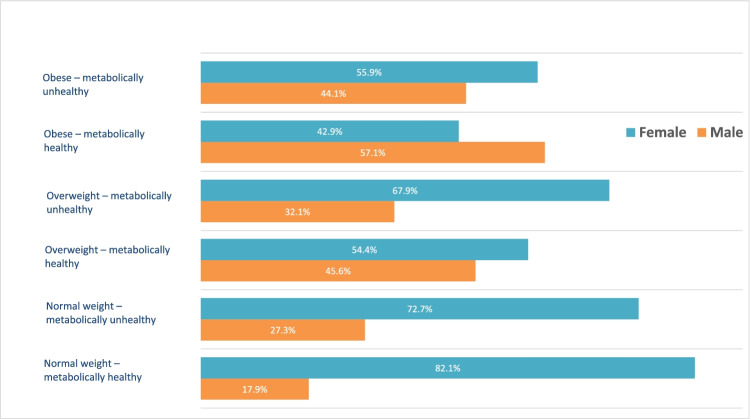

The response rate was around 90% of subjects invited to participate. All females included in this study were premenopausal, as ascertained by the clinical questionnaire. As expected, the prevalence of metabolic abnormalities increased with increasing BMI in both males and females (Fig. 1a). Overall, a higher percentage of males exhibited the unhealthy metabolic phenotypes (41.3% vs 27.8%; p < 0.001) (Fig. 1b). A total of 10.3% of normal weight males and 6.3% of normal weight females exhibited the MUHNW phenotype. While 73.9% of male and 82% of female overweight subjects exhibited the MHOW phenotype, only 25.7% of men and 36.5% of women had the MHO phenotype (Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1.

a Differences in prevalence of the six body composition phenotypes within the male and female populations. The prevalence of the metabolically unhealthy phenotype increased with increasing BMI categories in both sexes. b Proportion of males and females exhibiting the healthy or unhealthy metabolic phenotype. A higher proportion of males carried the unhealthy metabolic phenotype while a higher proportion of females exhibited the healthy metabolic phenotype

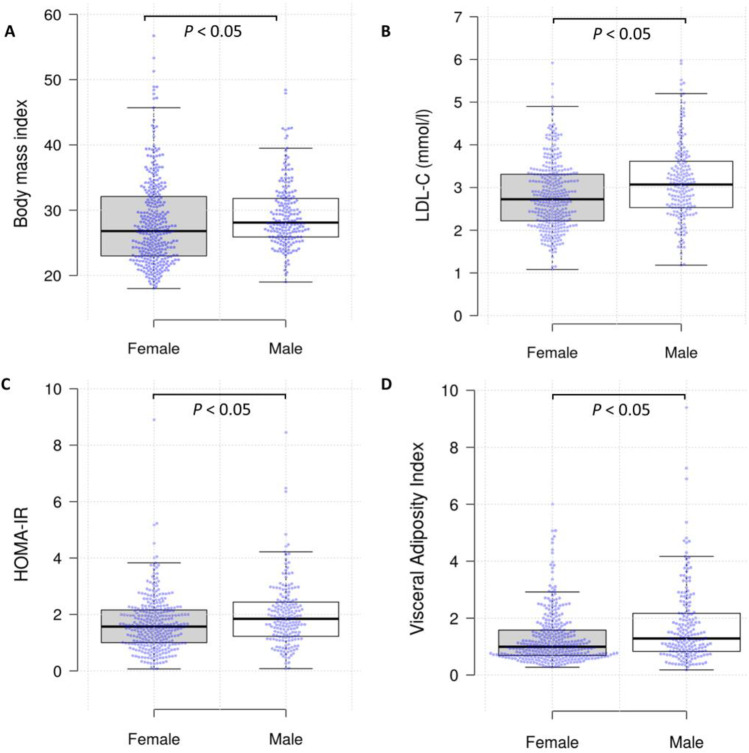

Table 1 and Fig. 2 compare the anthropometric and biochemical and lifestyle parameters between males and females in the entire study population. Overall, male participants had a less favourable metabolic profile, with a higher FPG, HbA1c, HOMA-IR, lipid accumulation product, visceral adiposity index, abdominal volume index, conicity index, body roundedness index, and ‘A’ body shaped index when compared with their female counterparts.

Table 1.

Sex differences in demographic, anthropometric, and biochemical (metabolic) parameters and indices of obesity measurement in the entire study population

| Variable | Male n = 191 (36.7%) |

Female n = 330 (63.3%) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| MHNW, n (%) | 26 (5.0) | 119 (22.8) | < 0.05 |

| MUHNW, n (%) | 3 (0.5) | 8 (1.5) | NS |

| MHOW, n (%) | 67 (12.8) | 81 (15.5) | < 0.05 |

| MUHOW, n (%) | 24 (4.6) | 18 (3.5) | < 0.05 |

| MHO, n (%) | 18 (3.5) | 38(7.3) | NS |

| MUHO, n (%) | 52 (10) | 66 (12.7) | NS |

| Demographic parameters | |||

| Age (IQR) | 42.0 (6.0) | 40.0 (7.0) | 0.024 |

| % Alcohol drinkers | 63.5 | 38.7 | < 0.01 |

| % Smokers | 25.7 | 20.6 | NS |

| % Regular physical activity | 48.7 | 39.4 | 0.024 |

| % White collar occupation | 57.1 | 71.2 | < 0.01 |

| % PMH | 23.0 | 20.9 | NS |

| % Tertiary education | 43.5 | 55.2 | 0.036 |

| Metabolic syndrome components | |||

| % WC ≥ 102 cm (M) or ≥ 88 cm (F) | 31.4 | 39.1 | 0.048 |

| % FPG ≥ 5.6 mmol/L | 33.0 | 15.8 | < 0.01 |

| %HOMA-IR ≥ 2.5 | 22.9 | 15.3 | 0.022 |

| % SBP ≥ 130 mmHg or DBP ≥ 85 mmHg or on anti-hypertensives | 46.6 | 38.5 | 0.043 |

| % TG ≥ 1.7 mmol/L or on statins | 36.1 | 11.2 | < 0.01 |

| % HDL-C ≤ 1.29 mmol/L (F) or ≤ 1.02 mmol/L (M) or on statins | 27.2 (26.4) | 26.4 | NS |

| Anthropometric parameters | |||

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 28.1 (5.2) | 26.8 (9.1) | 0.001 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 96.0 (16.0) | 83.0 (21.0) | < 0.001 |

| Hip circumference (cm) | 101.0 (11.0) | 97.8 (18.0) | 0.008 |

| Neck circumference (cm) | 39.0 (5.0) | 33.0 (4.50) | < 0.001 |

| Mean arm circumference (cm) | 31.0 (4.0) | 28.0 (5.00) | < 0.001 |

| Mean thigh circumference (cm) | 51.0 (8.0) | 53.0 (8.0) | 0.021 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 120.0 (13.0) | 120.0 (10.00) | NS |

| DBP (mmHg) | 80.0 (5.0) | 80.0 (15.00) | 0.029 |

| Biochemical parameters | |||

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | 4.98 (1.32) | 4.76 (1.11) | 0.012 |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 3.07 (1.11) | 2.73 (1.09) | < 0.001 |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 1.26 (0.41) | 1.54 (0.53) | < 0.001 |

| Triglycerides (mmol/L) | 1.25 (0.99) | 0.89 (0.61) | < 0.001 |

| Uric acid (µmol/L) | 329.00 (90.00) | 249.00 (82.0) | < 0.001 |

| Fasting plasma glucose (mmol/l) | 5.33 (0.82) | 5.03 (0.55) | < 0.001 |

| HbA1c (%) | 5.40 (0.50) | 5.20 (0.40) | < 0.001 |

| HOMA-IR | 1.85 (1.21) | 1.57 (1.16) | 0.001 |

| Vitamin D (ng/L) | 18.0 (9.0) | 18.0 (8.0) | NS |

| ALP (U/l) | 65.0 (19.0) | 61.5 (22.0) | 0.001 |

| GGT (U/l) | 28.0 (24.0) | 15.0 (11.0) | < 0.001 |

| ALT (U/l) | 26.0 (17.0) | 15.0 (8.0) | < 0.001 |

| Ferritin (ng/mL) | 153.0 (141.0) | 27.0 (41.0) | < 0.001 |

| TSH (micIU/mL) | 1.45 (0.86) | 1.49 (1.15) | NS |

| fT4 (pmol/L) | 15.20 (2.38) | 14.43 (2.23) | < 0.001 |

| Birth weight (kg) | 3.20 (1.28) | 3.20 (0.86) | 0.966 |

| Lipid accumulation product | 41.14 (46.93) | 21.81 (26.87) | < 0.001 |

| log (TG/HDL-C) | 0.00 (0.42) | -0.25 (0.35) | < 0.001 |

| Platelet-lymphocyte ratio | 117.7 (46.5) | 143.3 (60.8) | < 0.001 |

| Neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio | 1.91 (0.77) | 2.09 (1.03) | 0.001 |

| Indices of obesity measurement | |||

| Visceral adiposity index | 1.28 (1.28) | 0.99 (0.89) | < 0.001 |

| Waist-height ratio | 0.54 (0.09) | 0.52 (0.13) | < 0.001 |

| Waist-thigh ratio | 1.85 (0.31) | 1.58 (0.28) | < 0.001 |

| Body adiposity index | 25.68 (5.03) | 30.65 (9.93) | < 0.001 |

| Conicity index | 1.25 (0.11) | 1.16 (0.16) | < 0.001 |

| Abdominal volume index | 18.44 (6.18) | 14.15 (7.22) | < 0.001 |

| Body roundness index | 4.24 (1.90) | 3.71 (2.56) | < 0.001 |

| ‘A’ body shaped index | 0.14 (0.01) | 0.12 (0.01) | < 0.001 |

| Waist-hip ratio | 0.95 (0.09) | 0.84 (0.10) | < 0.001 |

| Waist index | 1.02 (0.17) | 1.02 (0.26) | NS |

Data are expressed as number and percentage, or median + IQR

MHNW metabolically healthy normal weight, MUHNW metabolically unhealthy normal weight, MHOW metabolically healthy overweight, MUHOW metabolically unhealthy overweight, MHO metabolically healthy obese, MUHO metabolically unhealthy obese

Metabolically healthy — individuals having ≤ 1 NCEP ATPIII criteria (consisting of waist circumference > 102 cm in men and > 88 cm in women; systolic or diastolic blood pressure ≥ 130/85 mmHg or on antihypertensive medication; serum triglyceride level ≥ 1.69 mmol/L or on lipid-lowering medication; HDL-C < 1.03 mmol/L in men and < 1.29 mmol/L in women or on treatment aimed to increase HDL-C; fasting glucose ≥ 5.6 mmol/L or on antihyperglycemic agents

Metabolically unhealthy— individuals having ≥ 2 metabolic abnormalities of the NCEP ATPIII criteria

SBP systolic blood pressure, DBP diastolic blood pressure, HOMA-IR homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance, TG triglycerides, HDL-C high density lipoprotein cholesterol, LDL-C low density lipoprotein cholesterol, PMH past medical history, FPG fasting plasma glucose, HBA1c haemoglobin A1c, ALP alkaline phosphatase, GGT gamma glutamyl transferase, ALT alanine transaminase, TSH thyroxine stimulating hormone, FT4 free thyroxine, NS not significant

Categorical variables are compared using the Chi-square test, and continuous variables are compared using the independent-samples Mann–Whitney U test. A p-value of < 0.05 is considered significant

Fig. 2.

Box and whiskers plot showing distribution of A BMI, B LDL-C, C HOMA-IR, and D VAI stratified by gender. Centre lines show the medians; box limits indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles; whiskers extend 1.5 times the interquartile range from the 25th and 75th percentiles; individual data points are plotted as blue circles. A statistically significant difference in these four parameters across genders was observed (Mann–Whitney U-test)

On the other hand, despite males having a higher median BMI, there was a lower proportion of males than females having an abnormally high WC (14% vs 37.8%; p < 0.01). Males also exhibited higher median arm circumference. Conversely, females had a larger median thigh circumference and lower waist-to-hip, waist-to-height, and waist-to-thigh ratios.

When considering the total population, a higher percentage of males exhibited the unhealthy overweight phenotype (4.6% vs 3.5%), but a higher percentage of females had the unhealthy obese phenotype (12.7% vs 10.0%). Finally, when sex stratification was analyzed for each category of metabolic health, a significant difference in sex distribution was noted for each body composition phenotype (Figure 3).

Fig. 3.

Prevalence of the various body size phenotypes by gender

In the MHNW group, males had a higher BMI, and neck, hip, and arm circumferences, as well as waist-to-hip and waist-to-thigh ratios, but similar waist index and thigh circumference to female subjects. Even though they were categorized as being metabolically healthy, male participants had a less favourable metabolic profile than their female counterparts. They, in fact, had higher FPG, LDL-C, TG, HOMA-IR, lipid accumulation product, abdominal volume index, conicity index, body roundedness index, and ‘A’ body shaped index and a lower HDL (Table 2).

Table 2.

Sex differences in demographic, anthropometric, and biochemical (metabolic) parameters and indices of obesity measurement in the metabolically healthy normal weight (MHNW) group

| Male n = 26 (17.9%) |

Female n = 119 (82.1%) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic parameters | |||

| Age (IQR) | 41.5 (8.0) | 40 (6.0) | NS |

| % Alcohol drinkers | 69.2 | 50.4 | 0.015 |

| % Smokers | 26.9 | 23.5 | NS |

| % Regular physical activity | 42.3 | 52.1 | NS |

| % White collar occupation | 53.0 | 75.6 | 0.045 |

| % PMH | 0 | 16.0 | 0.018 |

| % Tertiary education | 50.0 | 58.8 | NS |

| Metabolic syndrome components | |||

| %WC ≥ 102 cm (M) or ≥ 88 cm (F) | 0 | 2.5 | NS |

| % FPG ≥ 5.6 mmol/L | 7.7 | 4.2 | NS |

| %HOMA-IR ≥ 2.5 | 0 | 4.2 | NS |

| % sysBP ≥ 130 mmHg or diastolic BP ≥ 85 mmHg or on anti-hypertensive Rx | 26.9 | 31.1 | NS |

| % TG ≥ 1.7 mmol/L or on statins | 0 | 0.8 | NS |

| % HDL-C ≤ 1.29 mmol/L (F) or ≤ 1.02 mmol/L (M) or on statins | 3.8 | 10.9 | NS |

| Anthropometric parameters | |||

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 23.7 (2.0) | 22.2 (2.5) | 0.01 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 83 (7.0) | 71.5 (7.5) | < 0.001 |

| Hip circumference (cm) | 94 (6.0) | 89 (7.0) | < 0.001 |

| Neck circumference (cm) | 36 (2.0) | 31 (3.0) | < 0.001 |

| Mean arm circumference (cm) | 28 (1.5) | 25.5 (3.0) | < 0.001 |

| Mean thigh circumference (cm) | 48 (5.0) | 49 (4.0) | NS |

| SBP (mmHg) | 120.0 (10) | 115 (15.0) | NS |

| DBP (mmHg) | 80.0 (0) | 80.0 (10.0) | NS |

| Biochemical parameters | |||

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | 4.96 (0.64) | 4.48 (1.21) | 0.025 |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 2.97 (0.57) | 2.44 (0.99) | 0.002 |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 1.48 (0.36) | 1.72 (0.51) | 0.011 |

| Triglycerides (mmol/L) | 0.89 (0.43) | 0.73 (0.33) | 0.02 |

| Uric acid (µmol/L) | 300 (74) | 230 (83) | < 0.001 |

| Fasting plasma glucose (mmol/L) | 5.03 (0.37) | 4.92 (0.55) | 0.044 |

| HbA1c (%) | 5.2 (0.4) | 5.1 (0.3) | NS |

| HOMA-IR | 1.1 (0.69) | 1.18 (0.91) | NS |

| Vitamin D (ng/L) | 21.5 (11) | 19 (9.0) | NS |

| ALP (U/L) | 64 (13.0)) | 52 (20.0) | 0.003 |

| GGT (U/L) | 21.5 (7.0) | 13 (7.0) | < 0.001 |

| ALT (U/L) | 19 (9.0) | 13 (7.0) | 0.001 |

| Ferritin (ng/mL) | 134 (138) | 25 (30) | < 0.001 |

| TSH (micIU/L) | 1.47 (1.03) | 1.49 (1.22) | NS |

| fT4 (pmol/L) | 15.77 (2.9) | 14.55 (2.11) | 0.005 |

| Birth weight (kg) | 4.0 (0.0) | 3.1 (0.75) | NS |

| Lipid accumulation product | 16.22 (8.53) | 10.4 (8.19) | 0.001 |

| log (TG/HDL-C) | -0.26 (0.27) | -0.37 (0.24) | 0.004 |

| Platelet-lymphocyte ratio | 141.2 (48.0) | 145.4 (55.4) | NS |

| Neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio | 2.02 (0.66) | 2.09 (1.11) | NS |

| Indices of obesity measurement | |||

| Visceral adiposity index | 0.74 (0.54) | 0.74 (0.44) | 0.734 |

| Waist-hip ratio | 0.9 (0.06) | 0.81 (0.08) | < 0.001 |

| Waist index | 0.88 (0.07) | 0.88 (0.1) | 0.345 |

| Waist-height ratio | 0.49 (0.03) | 0.45 (0.05) | < 0.001 |

| Waist-thigh ratio | 1.7 (0.26) | 1.48 (0.19) | < 0.001 |

| Body adiposity index | 22.81 (2.06) | 25.98 (4.06) | < 0.001 |

| Conicity index | 1.21 (0.07) | 1.11 (0.11) | < 0.001 |

| Abdominal volume index | 14.09 (2.34) | 10.82 (2.17) | < 0.001 |

| Body roundness index | 3.09 (0.57) | 2.42 (0.83) | < 0.001 |

| ‘A’ body shaped index | 0.135 (0.014) | 0.117 (0.014) | < 0.001 |

Data are expressed as number and percentage, or median + IQR

MHNW metabolically healthy normal weight, MUHNW metabolically unhealthy normal weight, MHOW metabolically healthy overweight, MUHOW metabolically unhealthy overweight, MHO metabolically healthy obese, MUHO metabolically unhealthy obese

Metabolically healthy—individuals having ≤ 1 NCEP ATPIII criteria (consisting of waist circumference > 102 cm in men and > 88 cm in women; systolic or diastolic blood pressure ≥ 130/85 mmHg or on antihypertensive medication; serum triglyceride level ≥ 1.69 mmol/L or on lipid-lowering medication; HDL-C < 1.03 mmol/L in men and < 1.29 mmol/L in women or on treatment aimed to increase HDL-C; fasting glucose ≥ 5.6 mmol/L or on antihyperglycemic agents

Metabolically unhealthy—individuals having ≥ 2 metabolic abnormalities of the NCEP ATPIII criteria

SBP systolic blood pressure, DBP diastolic blood pressure, HOMA-IR homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance, TG triglycerides, HDL-C high density lipoprotein cholesterol, LDL-C low density lipoprotein cholesterol, PMH past medical history, FPG fasting plasma glucose, HBA1c haemoglobin A1c, ALP alkaline phosphatase, GGT gamma glutamyl transferase, ALT alanine transaminase, TSH thyroxine stimulating hormone, FT4 free thyroxine, NS not significant

Categorical variables are compared using the Chi-square test, and continuous variables are compared using the independent-samples Mann–Whitney U test. A p-value of < 0.05 is considered significant

In the MHOW/Ob group, males had higher neck circumference, arm circumference, and waist-to-hip and waist-to-thigh ratios; however, they had lower thigh circumference and waist index as compared with females. Similar to the MHNW group, males had a worse metabolic profile than their female counterparts, even though they were categorized as being metabolically healthy. They, in fact, had higher FPG, HbA1c, LDL-C, TG, HOMA-IR, lipid accumulation product, abdominal volume index, conicity index, and ‘A’ body shaped index and a lower HDL (Table 3). Tables 3 and 4 compare clinical and biochemical characteristics in males and females in the MHOW/Ob and MUHOW/Ob categories respectively.

Table 3.

Sex differences in demographic, anthropometric, and biochemical (metabolic) parameters and indices of obesity measurement in the metabolically healthy overweight/obese (MHOW/Ob) group

| Male n = 85 (41.7%) | Female n = 119 (58.3%) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic parameters | |||

| Age (IQR) | 41 (6) | 40 (6) | NS |

| % Alcohol drinkers | 70 | 40.3 | < 0.01 |

| % Smokers | 19.8 | 16.0 | NS |

| % Regular physical activity | 57.0 | 37.0 | 0.003 |

| % White collar occupation | 65.1 | 68.9 | NS |

| % PMH | 9.3 | 13.4 | NS |

| % Tertiary education | 53.5 | 53.8 | NS |

| Metabolic syndrome components | |||

| %WC ≥ 102 cm (M) or ≥ 88 cm (F) | 14.0 | 37.8 | < 0.01 |

| % FPG ≥ 5.6 mmol/l | 12.8 | 3.4 | 0.011 |

| %HOMA-IR ≥ 2.5 | 7.1 | 6.2 | NS |

| % SBP ≥ 130 mmHg or DBP ≥ 85 mmHg or on anti-hypertensive Rx | 32.6 | 38.7 | NS |

| % TG ≥ 1.7 mmol/l or on statins | 75.0 | 25.0 | 0.006 |

| % HDL-C ≤ 1.29 mmol/l (F) or ≤ 1.02 mmol/l (M) or on statins | 42.0 | 58.0 | NS |

| Anthropometric parameters | |||

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 27.5 (3.0) | 28.2 (4.9) | NS |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 92 (11.0) | 85.0 (14.0) | < 0.001 |

| Hip circumference (cm) | 99.0 (8.0) | 102.0 (13.5) | NS |

| Neck circumference (cm) | 38.0 (3.0) | 33.0 (3.5) | < 0.001 |

| Mean arm circumference (cm) | 30.5 (4.0) | 29.5 (3.0) | .002 |

| Mean thigh circumference (cm) | 51.0 (6.5) | 55.8 (7.0) | < 0.001 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 120 (10) | 120 (10) | NS |

| DBP (mmHg) | 80 (5) | 80 (10) | NS |

| Biochemical parameters | |||

| Total cholesterol (mmol/l) | 4.91 (1.3) | 4.77 (0.88) | NS |

| LDL-C (mmol/l) | 3.05 (1.01) | 2.71 (0.95) | .016 |

| HDL-C (mmol/l) | 1.32 (0.34) | 1.6 (0.49) | < 0.001 |

| Triglycerides (mmol/l) | 1.09 (0.58) | 0.85 (0.44) | < 0.001 |

| Uric acid | 322 (74) | 246 (72) | < 0.001 |

| Fasting plasma glucose (mmol/l) | 5.16 (0.58) | 5.02 (0.38) | 0.019 |

| HbA1c (%) | 5.3 (0.5) | 5.2 (0.3) | < 0.001 |

| HOMA-IR | 1.63 (0.95) | 1.61 (0.84) | NS |

| Vitamin D (ng/L) | 18 (11) | 18 (8) | NS |

| ALP (U/l) | 65.5 (20.0) | 61 (21) | NS |

| GGT (U/l) | 27 (22) | 14 (9) | < 0.001 |

| ALT (U/l) | 26.0 (15.0) | 14 | < 0.001 |

| Ferritin (ng/ml) | 134.5 (126.0) | 27 | < 0.001 |

| TSH (micIU/l) | 1.48 (0.91) | 1.48 (0.91) | NS |

| fT4 (pmol/L) | 15.23 (2.07) | 14.38 (2.32) | 0.002 |

| Birth weight (kg) | 3.2 (1.1) | 3.1 (1.1) | NS |

| Lipid accumulation product | 30.6 (22.2) | 23.0 (18.7) | 0.002 |

| log (TG/HDL-C) | -0.09 (0.28) | -0.3 (0.24) | < 0.001 |

| Platelet-lymphocyte ratio | 121.8 (44.0) | 147.0 (64.1) | < 0.001 |

| Neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio | 1.91 (0.76) | 1.98 (0.92) | NS |

| Indices of obesity measurement | |||

| Visceral adiposity index | 1.04 (0.73) | 0.90 (0.52) | NS |

| Waist-hip ratio | 0.92 (0.07) | 0.83 (0.1) | < 0.001 |

| Waist index | 1.0 (0.13) | 1.06 (0.16) | < 0.001 |

| Waist-height ratio | 0.52 (0.07) | 0.53 (0.08) | NS |

| Waist-thigh ratio | 1.79 (0.23) | 1.6 (0.31) | < 0.001 |

| Body adiposity index | 25.2 (3.5) | 32.3 (7.21) | < 0.001 |

| Conicity index | 1.22 (0.09) | 1.15 (0.16) | < 0.001 |

| Abdominal volume index | 17.0 (4.1) | 15.0 (4.34) | < 0.001 |

| Body roundness index | 3.84 (1.37) | 3.84 (1.65) | NS |

| ‘A’ body shaped index | 0.134 (0.012) | 0.114 (0.014) | < 0.001 |

Data are expressed as number and percentage, or median + IQR

Metabolically healthy—individuals having ≤ 1 NCEP ATPIII criteria (consisting of waist circumference > 102 cm in men and > 88 cm in women; systolic or diastolic blood pressure ≥ 130/85 mmHg or on antihypertensive medication; serum triglyceride level ≥ 1.69 mmol/L or on lipid-lowering medication; HDL-C < 1.03 mmol/L in men and < 1.29 mmol/L in women or on treatment aimed to increase HDL-C; fasting glucose ≥ 5.6 mmol/L or on antihyperglycemic agents

Metabolically unhealthy—individuals having ≥ 2 metabolic abnormalities of the NCEP ATPIII criteria

M male, F female, SBP systolic blood pressure, DBP diastolic blood pressure, HOMA-IR homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance, TG triglycerides, HDL-C high density lipoprotein cholesterol, LDL-C low density lipoprotein cholesterol, PMH past medical history, FPG fasting plasma glucose, HBA1c haemoglobin A1c, ALP alkaline phosphatase, GGT gamma glutamyl transferase, ALT alanine transaminase, TSH thyroxine stimulating hormone, FT4 free thyroxine, NS not significant

Categorical variables are compared using the Chi-square test, and continuous variables are compared using the independent-samples Mann–Whitney U test. A p-value of < 0.05 is considered significant

Table 4.

Sex differences in demographic, anthropometric, and biochemical (metabolic) parameters and indices of obesity measurement in the metabolically unhealthy overweight/obese (MUHOW/Ob)

| Male n = 76 (47.5%) |

Female n = 84 (52.5%) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic parameters | |||

| Age (IQR) | 42 (5) | 41.5 (7) | NS |

| % Alcohol drinkers | 53.9 | 22.6 | < 0.01 |

| % Smokers | 32.9 | 21.4 | 0.027 |

| % Regular physical activity | 42.1 | 25.0 | 0.017 |

| % White collar occupation | 50.0 | 69.0 | 0.001 |

| % PMH | 44.7 | 35.7 | NS |

| % Tertiary education | 30.3 | 53.6 | 0.012 |

| Metabolic syndrome components | |||

| %WC ≥ 102 cm (M) or ≥ 88 cm (F) | 61.8 | 94.0 | < 0.01 |

| % FPG ≥ 5.6 mmol/L | 63.2 | 46.4 | 0.025 |

| %HOMA-IR ≥ 2.5 | 49.3 | 42.2 | NS |

| % SBP ≥ 130 mmHg or DBP ≥ 85 mmHg or on anti-hypertensive Rx | 69.7 | 46.4 | 0.002 |

| % TG ≥ 1.7 mmol/L or on statins | 71.1 | 33.3 | < 0.01 |

| % HDL-C ≤ 1.29 mmol/L (F) or ≤ 1.02 mmol/L (M) or on statins | 57.9 | 67.9 | NS |

| Anthropometric parameters | |||

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 31.9 (5.5) | 34.2 (8.4) | 0.003 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 106 (14.5) | 100.0 (15.5) | 0.012 |

| Hip circumference (cm) | 106.3 (13.0) | 113.5 (19) | 0.001 |

| Neck circumference (cm) | 41.0 (3.75) | 36.0 (3.5) | < 0.001 |

| Mean arm circumference (cm) | 33.0 (3.0) | 33.0 (5.5) | NS |

| Mean thigh circumference (cm) | 53.5 (5.6) | 58.0 (8.0) | < 0.001 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 120 (14.5) | 124.5 (13) | NS |

| DBP (mmHg) | 85 (10) | 80 (5) | 0.025 |

| Biochemical parameters | |||

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | 5.12 (1.4) | 4.89 (1.1) | NS |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 3.16 (1.23) | 3.13 (1.01) | NS |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 1.06 (0.31) | 1.25 (0.29) | < 0.001 |

| Triglycerides (mmol/L) | 1.91 (1.14) | 1.43 (0.71) | < 0.001 |

| Uric acid | 349 (84) | 273 75) | < 0.001 |

| Fasting blood glucose (mmol/L) | 5.75 (1.07) | 5.52 (0.92) | 0.016 |

| HbA1c (%) | 5.7 (0.7) | 5.4 (0.5) | 0.001 |

| HOMA-IR | 2.47 (1.36) | 2.27 (1.3) | NS |

| Vitamin D (ng/L) | 17 (5.5) | 17.5 (7) | NS |

| ALP (U/L) | 67.5 (22.5) | 70.5 (17) | NS |

| GGT (U/L) | 33.5 (28.5) | 21 (12.5) | < 0.001 |

| ALT (U/L) | 27 (22) | 19 (10) | < 0.001 |

| Ferritin (ng/mL) | 178 (151.5) | 29.5 (60) | < 0.001 |

| TSH (micIU/L) | 1.46 (0.61) | 1.6 (1.42) | NS |

| fT4 (pmol/L) | 14.94 (2.53) | 14.25 (2.45) | NS |

| Birth weight (kg) | 3.0 (0.8) | 3.55 (0.72) | NS |

| Lipid accumulation product | 70.6 (42.62) | 57.74 (48.73) | 0.014 |

| log (TG/HDL-C) | 0.24 (0.37) | 0.07 (0.25) | < 0.001 |

| Platelet-lymphocyte ratio | 110.9 (47.42) | 140.99 (67.19) | < 0.001 |

| Neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio | 1.9 (0.82) | 2.22 (0.91) | < 0.001 |

| Indices of obesity measurement | |||

| Visceral adiposity index | 2.23 (1.96) | 2.07 (1.2) | NS |

| Waist-hip ratio | 0.98 (0.09) | 0.88 (0.08) | < 0.001 |

| Waist index | 1.1 (0.14) | 1.21 (0.2) | < 0.001 |

| Waist-height ratio | 0.6 (0.08) | 0.63 (0.08) | 0.026 |

| Waist-thigh ratio | 1.97 (0.25) | 1.71 (0.22) | < 0.001 |

| Body adiposity index | 27.86 (5.77) | 37.25 (10.38) | < 0.001 |

| Conicity index | 1.28 (0.08) | 1.24 (0.09) | < 0.001 |

| Abdominal volume index | 22.47 (6.01) | 20.4 (6.68) | 0.05 |

| Body roundness index | 5.44 (1.85) | 6.17 (2.0) | 0.025 |

| ‘A’ body shaped index | 0.137 (0.012) | 0.12 (0.012) | < 0.001 |

Data are expressed as number and percentage, or median + IQR

Metabolically healthy—individuals having ≤ 1 NCEP ATPIII criteria (consisting of waist circumference > 102 cm in men and > 88 cm in women; systolic or diastolic blood pressure ≥ 130/85 mmHg or on antihypertensive medication; serum triglyceride level ≥ 1.69 mmol/L or on lipid-lowering medication; HDL-C < 1.03 mmol/L in men and < 1.29 mmol/L in women or on treatment aimed to increase HDL-C; fasting glucose ≥ 5.6 mmol/L or on antihyperglycemic agents

Metabolically unhealthy—individuals having ≥ 2 metabolic abnormalities of the NCEP ATPIII criteria

M male, F female, SBP systolic blood pressure, DBP diastolic blood pressure, HOMA-IR homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance, TG triglycerides, HDL-C high density lipoprotein cholesterol, LDL-C low density lipoprotein cholesterol, PMH past medical history, FPG fasting plasma glucose, HBA1c haemoglobin A1c, ALP alkaline phosphatase, GGT gamma glutamyl transferase, ALT alanine transaminase, TSH thyroxine stimulating hormone, FT4 free thyroxine, NS not significant

Categorical variables are compared using the Chi-square test, and continuous variables are compared using the independent-samples Mann–Whitney U test. A p-value of < 0.05 is considered significant

Meaningful statistical comparison of differences between males (n=3) and females (n=8) classified as MUHNW is limited by the small number of subjects in this category (data not shown).

Clinical predictors of HOMA-IR were evaluated using generalized linear modelling. In males, BMI was the only significant predictor of HOMA-IR (β= 0.082, 95% CI 0.046–0.119, p < 0.01). In females, BMI (β = 0.047, 95% CI 0.032–0.062, p < 0.01) and WHR (β = 1.91, 95% CI 0.362–3.45, p = 0.016) were identified as significant predictors of HOMA-IR. Effect size estimates of BMI and WHR under different models are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Clinical predictors of HOMA-IR. Generalized linear modelling specifying gamma as the distribution and log as the link function was applied to identify significant predictors of HOMA-IR separately in males and females. Simple bedside clinical parameters were included as scale (age, waist:hip ratio, BMI, and neck circumference) or categorical independent variables (smoking, physical activity, alcohol consumption). In males, BMI emerged as the only significant predictor of HOMA-IR, whereas in females, both BMI and WHR exceeded significance thresholds

| Males | Females | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

| β (95% CI), p-value | β1 (95% CI), p-value | β2 (95% CI), p-value | β3 (95% CI), p-value | |

| Age | 0.007 (− 0.032 to 0.046), p = 0.74 | 0.008 (− 2.988 to 0.018), p = 0.06 | ||

| BMI | 0.082 (0.046–0.119), p < 0.01 | 0.047 (0.032–0.061), p < 0.01 | 0.048 (0.033–0.062), p < 0.01 | |

| Neck circumference | − 0.016 (− 0.04 to 0.008), p = 0.202 | − 0.003 (− 0.017 to 0.012), p = 0.702 | ||

| Waist:hip ratio | 0.299 (− 2.33 to 2.99), p = 0.824 | 1.91 (0.362 – 3.459), p = 0.016 | 2.18 (0.547–3.82), p = 0.009 | |

| Physical activity | 0.058 (− 0.245 to 0.362), p = 0.708 | 0.077 (− 0.127 to 0.281), p = 0.458 | ||

| Smoking | − 0.197 (− 0.514 to 0.121), p = 1.47 | 0.013 (− 0.203 to 0.23), p = 0.903 | ||

| Alcohol consumption | − 0.216 (− 0.515 to 0.118), p = 0.206 | − 0.109 (− 0.315 to 0.097), p = 0.299 | ||

β1 total effect of BMI and WHR on HOMA-IR in females, β2 total effect of BMI on HOMA-IR in females, β3 total effect of WHR on HOMA-IR in females

Discussion

In this study, we sought to explore sex differences in the prevalence of adiposity-metabolic health phenotypes in a well-phenotyped Maltese-Caucasian population. Using a nationally representative sample of middle-aged adults, gender differences across different definitions of metabolic health were evaluated and compared. Our results are relevant and new in the context of a regional island population with a high prevalence of cardio-metabolic disease. We used the NCEPATP III parameters to define metabolic health as these criteria are easily reproducible and have been linked with cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality in different studies (Zheng et al., 2016).

The prevalence of the metabolically healthy phenotype was higher in females. Overall, males demonstrated a pro-atherogenic metabolic profile, including higher plasma glucose, triglycerides, total cholesterol, and LDL-C as well as lower HDL-C. The less favourable biochemical profile in males was also observed within the healthy normal weight, healthy overweight/obese, and unhealthy overweight/obese categories. There were too few subjects in the unhealthy normal weight category for meaningful comparison. We found that males were more likely to be metabolically unhealthy, despite higher levels of alcohol consumption and a higher reported physical activity. Physical exercise is well established as being associated with improved metabolic health (Shabkhiz et al., 2020; Al-Rashed et al., 2020; Pettman et al., 2009; Che and Li 2017). Although alcohol consumption is associated with a rise in serum triglycerides, it has nonetheless been linked to improved metabolic health by some (Enríquez Martínez et al., 2019; Muga et al., 2019; Rosoff et al., 2019) but not all authors (Würtz et al., 2016). Furthermore, there was a higher proportion of males who were insulin resistant (HOMA ≥ 2.5) as compared with females.

Our data suggest that contemporary middle-aged males are inherently more metabolically unhealthy than middle-aged females. This may be partly related to the secular decline in serum testosterone in males over the last few decades, which has been reported by various authors (Mazur et al., 2013; Perheentupa et al., 2013). Testosterone is known to improve several metabolic parameters, including blood lipids and insulin sensitivity (Kelly and Jones 2013). The reasons for the secular decline in serum testosterone are unknown. It cannot be solely explained by increasing male obesity (Mazur et al., 2013). Possible additional mechanisms include dietary factors (Fantus et al., 2020) and environmental pollutants (Scinicariello and Buser 2016).

Since even normal weight males were more often metabolically unhealthy than normal weight women, our data also suggest that sex-specific BMI cut-offs may be necessary to better categorize individuals. This merits further investigation. There was a lower proportion of males exhibiting an abnormally high waist circumference when compared to females, despite having a less favourable metabolic profile (in terms of glycaemic, lipid and liver enzyme parameters) and in spite of being metabolically unhealthy more frequently. Our data suggest that the currently used cut-off for waist circumference according to the NCEP ATP III criteria (2002) and adopted by the American Heart Association and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (Grundy et al., 2005) may be too high in males, at least in some populations. It should be noted that the current cut-offs were developed 20 years ago (2001). The decline in serum testosterone levels over the last decades (Mazur et al., 2013; Perheentupa et al., 2013) may have altered the relation between waist circumference and visceral fat. Testosterone has been shown to reduce visceral, but not subcutaneous, adipocyte size (Abdelhamed et al., 2015) in animal models. Furthermore, androgen deprivation therapy in humans has been reported to cause a greater increase in visceral fat area than in subcutaneous fat area (Hamilton et al., 2011). In these patients, there was a significant negative association between total testosterone and visceral, but not subcutaneous, fat area (Hamilton et al., 2011). It is therefore possible that the secular decline in serum testosterone in males over the last decades has resulted in a lower waist circumference being predictive of insulin resistance in males. In our study, the waist index was similar in males and females, but this is a derived index based on current cut-offs. If a lower cut-off were to be used, the median waist index would have been higher in males, which would be consistent with their worse metabolic parameters. Again, this suggests that the current cut-offs may be too high for males. It should be noted that males have more visceral fat for a given waist circumference (Camhi et al., 2011; Kuk et al., 2005). Males also had higher waist-to-hip, waist-to-height, and waist-to-thigh ratios.

On the other hand, women exhibited higher neutrophil–lymphocyte and platelet-lymphocyte ratios, both of which have been associated with increased cardiovascular risk (Horne et al., 2005; Dentali et al. 2018). The divergence of metabolic and haematological risk factors between the two sexes may be related to sex differences in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease. Both the neutrophil–lymphocyte and platelet-lymphocyte ratios are associated with microvascular disease (Fawwad et al. 2018; Okyay et al. 2015), which is thought to be a more important pathogenic mechanism in females (Seidelmann et al., 2016; Wong et al., 2002).

Our data also suggest that anthropometric measurements that best predict insulin resistance may differ according to sex. We found that BMI was the only significant independent predictor of HOMA-IR in males, while both BMI and WHR were significant independent predictors in females. This may be due to males having a higher proportion of visceral and ectopic fat for a given BMI than females (Rossi et al., 2011). On the other hand, females tend to have more subcutaneous fat (Camhi et al., 2011), which has been reported to be associated with increased leptin expression (Montague et al., 1997). Leptin has been shown to improve insulin sensitivity (D’souza et al., 2017; German et al., 2010; Levi et al., 2011). Since waist circumference in females is a stronger marker for abdominal subcutaneous fat than for visceral fat and since subcutaneous fat also contributes to the hip circumference, the waist-hip ratio may be a better marker of visceral adiposity than the uncorrected waist circumference in females.

This study has some limitations. We have no data on pro-inflammatory cytokines, cardiorespiratory fitness, or diet. Furthermore, BMI was used as an index of obesity measurement; and thus, it could have misclassified individuals with short stature or decreased muscle mass. However, we studied a middle-aged population in whom sarcopenia is uncommon. We used standard definitions to characterize the metabolically healthy from unhealthy phenotypes and to define insulin resistance. The cross-sectional design also limits direct evaluation of the interaction between body composition phenotypes and sex in the consequent development of cardiometabolic disease.

A major strength of this study is that we studied a well-characterized and an adequately sized representative sample of middle-aged adult subjects. Other age groups should be studied separately since relationships between anthropometric parameters and metabolic health are likely to vary across different age groups because of age-related changes in muscle mass and function and in fat distribution. Standard methods for data collection and for the definition of metabolic health were used as already validated in previous studies. Biochemical parameters were centrally analyzed using appropriate quality controls.

Conclusion

We found that in a contemporary sample of middle-aged individuals, males were more metabolically unhealthy and more insulin resistant than females, despite exhibiting an abnormal waist circumference less frequently and having a similar waist index. This suggests that the currently used cut-offs for normal waist circumference should be revised downwards in males. Since even normal weight males were more likely to be metabolically unhealthy than normal weight females, BMI cut-offs may likewise need to be lowered in males. On the other hand, neutrophil–lymphocyte and platelet-lymphocyte ratios were both higher in females compared to males, which is consistent with established sex differences in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease. These relationships are likely to be strongly dependent on both age and ethnicity; hence, future studies should investigate different age and ethnic groups to better define the role of these parameters in the causal trajectory to cardiometabolic disease. The cross-sectional nature of the study limits the evaluation of the interaction between cardiometabolic alterations and the development of cardiovascular disease, which should be evaluated prospectively. Furthermore, our results require replication and validation in other contemporary populations.

Contributions to knowledge

What does this study add to existing knowledge?

Visceral adiposity is known to be more strongly associated with cardiovascular risk than subcutaneous adiposity.

There are sex differences in distribution of fat and in the prevalence of overweight and obesity.

In a contemporary sample of middle-aged individuals, a significantly higher percentage of males exhibited the unhealthy metabolic phenotype and males were more insulin resistant. On the other hand, females exhibited higher neutrophil–lymphocyte and platelet-lymphocyte ratios, both of which have been associated with increased cardiovascular risk.

Despite males having a higher median BMI, there was a lower proportion of males having an abnormally high waist circumference than females.

What are the key implications for public health interventions, practice or policy?

These data suggest that the currently used cut-offs for normal waist circumference should be revised downwards in males.

Since even normal weight males were more often metabolically unhealthy than normal weight women, BMI cut-offs may also need to be lowered in males.

The sex divergence between metabolic and haematological risk factors is consistent with sex differences in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease, which suggests that they may need to be treated differently.

Author contributions

All the authors were involved in the conception and the design of the study and in writing the manuscript. RA was additionally responsible for data collection.

Availability of data and material

Data available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Code availability

N/A.

Declarations

Ethics approval

This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical and data protection approvals were granted from the University of Malta Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine and Surgery and the Information and Data Protection Commissioner respectively. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Consent for publication

All the authors consent to publication of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Abdelhamed A, Hisasue S, Shirai M, et al. (2015) Testosterone replacement alters the cell size in visceral fat but not in subcutaneous fat in hypogonadal aged male rats as a late-onset hypogonadism animal model. Research and Reports in Urology. 2015;7:35–40. doi: 10.2147/RRU.S72253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Rashed, F., Alghaith, A., Azim, R., AlMekhled, D., Thomas, R., Sindhu, S., Ahmad, R. (2020). Increasing the duration of light physical activity ameliorates insulin resistance syndrome in metabolically healthy obese adults. Cells, 9(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Buscemi S, Chiarello P, Buscemi C, Corleo D, Massenti MF, Barile AM, Rosafio G, Maniaci V, Settipani V, Cosentino L, Giordano C. Characterization of metabolically healthy obese people and metabolically unhealthy normal-weight people in a general population cohort of the ABCD study. Journal of Diabetes Research. 2017;2017:9294038. doi: 10.1155/2017/9294038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camhi SM, Bray GA, Bouchard C, et al. The relationship of waist circumference and BMI to visceral, subcutaneous, and total body fat: Sex and race differences. Obesity (silver Spring) 2011;19(2):402–408. doi: 10.1038/oby.2010.248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Che L, Li D. The effects of exercise on cardiovascular biomarkers: New insights, recent data, and applications. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. 2017;999:43–53. doi: 10.1007/978-981-10-4307-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dentali F, Nigro O, Squizzato A, et al. Impact of neutrophils to lymphocytes ratio on major clinical outcomes in patients with acute coronary syndromes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature. International Journal of Cardiology. 2018;266:31–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2018.02.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhand, N. K., & Khatkar, M. S. (2014). http://statulator.com/SampleSize/ss1P.html (accessed 1 Sep 2019)

- D’souza, A. M., Neumann, U. H., Glavas, M. M., Kieffer, T. J. (2017). The glucoregulatory actions of leptin. Molecular Metabolism 6(9):1052–1065. Published 2017 May 4. 10.1016/j.molmet.2017.04.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Durward CM, Hartman TJ, Nickols-Richardson SM. All-cause mortality risk of metabolically healthy obese individuals in NHANES III. Journal of obesity. 2012;2012:460321. doi: 10.1155/2012/460321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyer AR, Stamler J, Garside DB, Greenland P. Long-term consequences of body mass index for cardiovascular mortality: The Chicago Heart Association Detection Project in Industry study. Annals of Epidemiology. 2004;14:101–108. doi: 10.1016/S1047-2797(03)00121-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elías-López D, Vargas-Vázquez A, Mehta R, Cruz Bautista I, Del Razo Olvera F, Gómez-Velasco D, Almeda Valdes P, Aguilar-Salinas CA. Metabolic Syndrome Study Group. Natural course of metabolically healthy phenotype and risk of developing Cardiometabolic diseases: A three years follow-up study. BMC Endocrine Disorders. 2021;21(1):85. doi: 10.1186/s12902-021-00754-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enríquez Martínez OG, Luft VC, Faria CP, Molina MDCB. Alcohol consumption and lipid profile in participants of the Longitudinal Study of Adult Health (ELSA-BRASIL) Nutricion Hospitalaria. 2019;36(3):665–673. doi: 10.20960/nh.2260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fantus RJ, Halpern JA, Chang C, et al. The association between popular diets and serum testosterone among men in the United States. Journal of Urology. 2020;203(2):398–404. doi: 10.1097/JU.0000000000000482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fawwad, A., Butt, A. M., Siddiqui, I. A., Khalid, M., Sabir, R., Basit, A. (2018). Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and microvascular complications in subjects with type 2 diabetes: Pakistan’s perspective. Turkish Journal of Medical Sciences 48(1):157–161. Published 2018 Feb 23. 10.3906/sag-1706-141. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ge W, Parvez F, Wu F, Islam T, Ahmed A, Shaheen I, Sarwar G, Demmer RT, Desvarieux M, Ahsan H, Chen Y. Association between anthropometric measures of obesity and subclinical atherosclerosis in Bangladesh. Atherosclerosis. 2014;232(1):234–241. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2013.11.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- German JP, Wisse BE, Thaler JP, et al. Leptin deficiency causes insulin resistance induced by uncontrolled diabetes. Diabetes. 2010;59(7):1626–1634. doi: 10.2337/db09-1918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundy, S. M., Cleeman, J. I., Daniels, S. R., Donato, K. A., Eckel, R. H., Franklin, B. A., Gordon, D. J., Krauss, R. M., Savage, P. J., Smith, S. C. Jr, Spertus, J. A., Costa, F. (2005). American Heart Association; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: an American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Scientific Statement. Circulation. Oct 25;112(17):2735–52. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.169404. Erratum in: Circulation. 2005 Oct 25;112(17):e297. Erratum in: Circulation. 2005 Oct 25;112(17):e298. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hamilton EJ, Gianatti E, Strauss BJ, et al. Increase in visceral and subcutaneous abdominal fat in men with prostate cancer treated with androgen deprivation therapy. Clinical Endocrinology - Oxford. 2011;74(3):377–383. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2010.03942.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermans MP, Ahn SA, Rousseau MF. The atherogenic dyslipidemia ratio [log(TG)/HDL-C] is associated with residual vascular risk, beta-cell function loss and microangiopathy in type 2 diabetes females. Lipids in Health and Disease. 2012;11:132. doi: 10.1186/1476-511X-11-132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horne BD, Anderson JL, John JM, et al. Which white blood cell subtypes predict increased cardiovascular risk? Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2005;45(10):1638–1643. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.02.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn HS. The “lipid accumulation product” performs better than the body mass index for recognizing cardiovascular risk: A population-based comparison. BMC Cardiovascular Disorders. 2005 doi: 10.1186/1471-2261-5-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly DM, Jones TH. Testosterone: A metabolic hormone in health and disease. The Journal of Endocrinology. 2013;217(3):R25–R45. doi: 10.1530/JOE-12-0455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuk JL, Lee S, Heymsfield SB, Ross R. Waist circumference and abdominal adipose tissue distribution: Influence of age and sex. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2005;81(6):1330–1334. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/81.6.1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapidus L, Bengtsson C, Larsson B, Pennert K, Rybo E, Sjöström L. Distribution of adipose tissue and risk of cardiovascular disease and death: A 12 year follow up of participants in the population study of women in Gothenburg. Sweden. Br Med J (clin Res Ed) 1984;289(6454):1257–1261. doi: 10.1136/bmj.289.6454.1257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levi J, Gray SL, Speck M, Huynh FK, Babich SL, Gibson WT, Kieffer TJ. Acute disruption of leptin signaling in vivo leads to increased insulin levels and insulin resistance. Endocrinology. 2011;152(9):3385–3395. doi: 10.1210/en.2011-0185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin L, Zhang J, Jiang L, Du R, Hu C, Lu J, Wang T, Li M, Zhao Z, Xu Y, Xu M, Bi Y, Ning G, Wang W, Chen Y. Transition of metabolic phenotypes and risk of subclinical atherosclerosis according to BMI: A prospective study. Diabetologia. 2020;63:1312–1323. doi: 10.1007/s00125-020-05116-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magri CJ, Fava S, Galea J. Prediction of insulin resistance in type 2 diabetes mellitus using routinely available clinical parameters. Diabetes and Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research and Reviews. 2016;10(2 Suppl 1):S96–S101. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2016.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews DR, Hosker JP, Rudenski AS, Naylor BA, Treacher DF, Turner RC. Homeostasis model assessment: Insulin resistance and beta-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia. 1985;28:412–419. doi: 10.1007/BF00280883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazur, A., Westerman, R., Mueller, U. (2013). Is rising obesity causing a secular (age-independent) decline in testosterone among American men?. PLoS One. 8(10):e76178. Published 2013 Oct 16. 10.1371/journal.pone.0076178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Montague CT, Prins JB, Sanders L, Digby JE, O'Rahilly S. Depot- and sex-specific differences in human leptin mRNA expression: Implications for the control of regional fat distribution. Diabetes. 1997;46(3):342–347. doi: 10.2337/diab.46.3.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muga MA, Owili PO, Hsu CY, Chao JC. Association of lifestyle factors with blood lipids and inflammation in adults aged 40 years and above: A population-based cross-sectional study in Taiwan. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1346. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-7686-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP). (2002). Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation, 106(25):3143–421. [PubMed]

- Okyay K, Yilmaz M, Yildirir A, et al. Relationship between neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and impaired myocardial perfusion in cardiac syndrome X. European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences. 2015;19(10):1881–1887. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parati G, Stergiou G, O'Brien E, et al. European Society of Hypertension practice guidelines for ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. Journal of Hypertension. 2014;32:1359–1366. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000000221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perheentupa, A., Mäkinen, J., Laatikainen, T., et al. (2013). A cohort effect on serum testosterone levels in Finnish men. European Journal of Endocrinology, 168(2):227–233. Published 2013 Jan 17. 10.1530/EJE-12-0288 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Pettman TL, Buckley JD, Misan GM, Coates AM, Howe PR. Health benefits of a 4-month group-based diet and lifestyle modification program for individuals with metabolic syndrome. Obesity Research & Clinical Practice. 2009;3:221–235. doi: 10.1016/j.orcp.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosoff DB, Charlet K, Jung J, Lee J, Muench C, Luo A, Longley M, Mauro KL, Lohoff FW. Association of high-intensity binge drinking with lipid and liver function enzyme levels. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(6):e195844. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.5844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi AP, Fantin F, Zamboni GA, et al. Predictors of ectopic fat accumulation in liver and pancreas in obese men and women. Obesity (silver Spring) 2011;19(9):1747–1754. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Chaparro MA, Calvo-Bonacho E, González-Quintela A, Fernández-Labandera C, Cabrera M, Sáinz JC, Fernández-Meseguer A, Banegas JR, Ruilope LM, Valdivielso P, Román-García J. Ibermutuamur Cardiovascular Risk Assessment (ICARIA) Study Group. Occupation-related differences in the prevalence of metabolic syndrome. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(9):1884–5. doi: 10.2337/dc08-0431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scinicariello F, Buser MC. Serum testosterone concentrations and urinary bisphenol a, benzophenone-3, triclosan, and paraben levels in male and female children and adolescents: NHANES 2011–2012. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2016;124(12):1898–1904. doi: 10.1289/EHP150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidelmann SB, Claggett B, Bravo PE, et al. Retinal vessel calibers in predicting long-term cardiovascular outcomes: The atherosclerosis risk in Communities study. Circulation. 2016;134(18):1328–1338. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.023425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shabkhiz, F., Khalafi, M., Rosenkranz, S., Karimi, P., Moghadami, K. (2020). Resistance training attenuates circulating FGF-21 and myostatin and improves insulin resistance in elderly men with and without type 2 diabetes mellitus: A randomised controlled clinical trial [published online ahead of print, 2020 May 26]. European Journal of Sport Science. 1‐10. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Thomas DM, Bredlau C, Bosy-Westphal A, et al. Relationships between body roundness with body fat and visceral adipose tissue emerging from a new geometrical model. Obesity (silver Spring) 2013;21:2264–2271. doi: 10.1002/oby.20408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Gaal LF, Mertens IL, De Block CE. Mechanisms linking obesity with cardiovascular disease. Nature. 2006;444(7121):875–880. doi: 10.1038/nature05487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wildman RP, Muntner P, Reynolds K, McGinn AP, Rajpathak S, Wylie-Rosett J, Sowers MR. The obese without cardiometabolic risk factor clustering and the normal weight with cardiometabolic risk factor clustering: Prevalence and correlates of 2 phenotypes among the US population (NHANES 1999–2004) Archives of Internal Medicine. 2008;168(15):1617–1624. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.15.1617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, Agabiti Rosei E, Azizi M, Burnier M, et al. 2018 ESC/ESH guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. European Heart Journal. 2018;39(33):3021–3104. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy339.Erratum.In:EurHeartJ.2019Feb1;40(5):475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong TY, Klein R, Sharrett AR, et al. Retinal arteriolar narrowing and risk of coronary heart disease in men and women. The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. JAMA. 2002;287(9):1153–1159. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.9.1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Würtz P, Cook S, Wang Q, Tiainen M, Tynkkynen T, Kangas AJ, et al. Metabolic profiling of alcohol consumption in 9778 young adults. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2016;45:1493–1506. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyw175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ounpuu S, Dans T, Avezum A, Lanas F, et al. Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): Case-control study. Lancet. 2004;364(9438):937–952. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17018-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng R, Zhou D, Zhu Y. The long-term prognosis of cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality for metabolically healthy obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2016;70(10):1024–1031. doi: 10.1136/jech-2015-206948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data available from the authors upon reasonable request.

N/A.