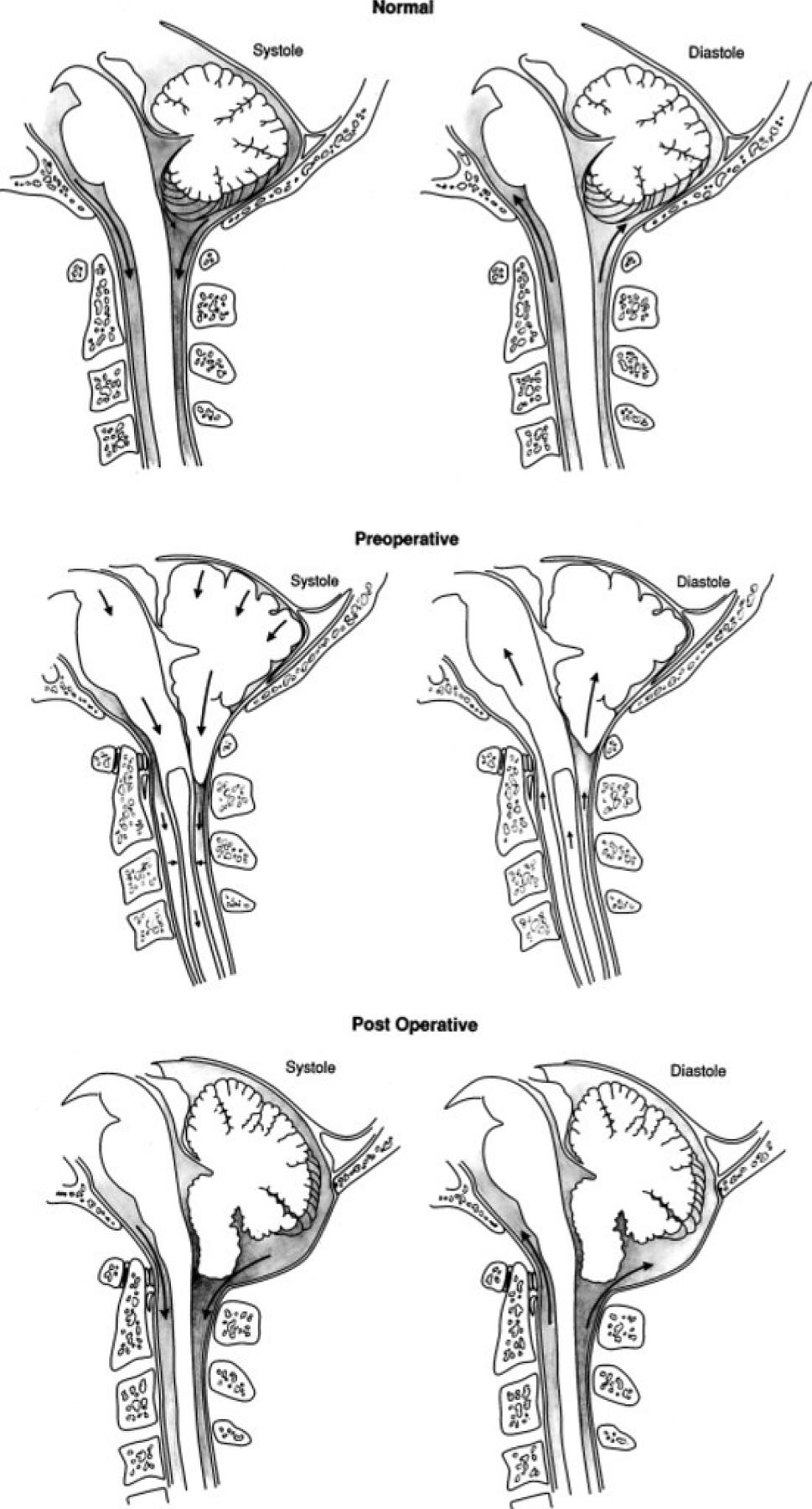

Figure 1.

Illustrations showing normal anatomy and flow of CSF in the subarachnoid space at the foramen magnum during the cardiac cycle in a normal healthy volunteer (upper); obstructed flow of CSF in the subarachnoid space at the foramen magnum resulting in the cerebellar tonsils’ acting as a piston on the cervical subarachnoid space, creating cervical subarachnoid pressure waves that compress the spinal cord from without and propagating syrinx fluid movement (center); and relief of the obstruction of the subarachnoid space at the foramen magnum, eliminating the mechanism of progression of syringomyelia (lower).

(Adapted from Heiss JD, Patronas N, DeVroom HL, et al. Elucidating the pathophysiology of syringomyelia. J Neurosurg. 1999;91(4):553-562. doi:10.3171/jns.1999.91.4.0553; with permission)