To the editor:

We read with great interest the clinical communication by McGowan et al. exploring the prevalence and geographic distribution of eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) among pediatric patients with Medicaid1. The authors observed that when accounting for race, EoE was less prevalent in rural America. This finding is noteworthy, as previous adult studies have shown that EoE prevalence is higher in rural population2. A major reason for these contradictory findings, as the authors point out, could be the focus on pediatric patients or less access to subspecialty care. Based on their findings, we hypothesized that rural health care disparities may exist in pediatric populations.

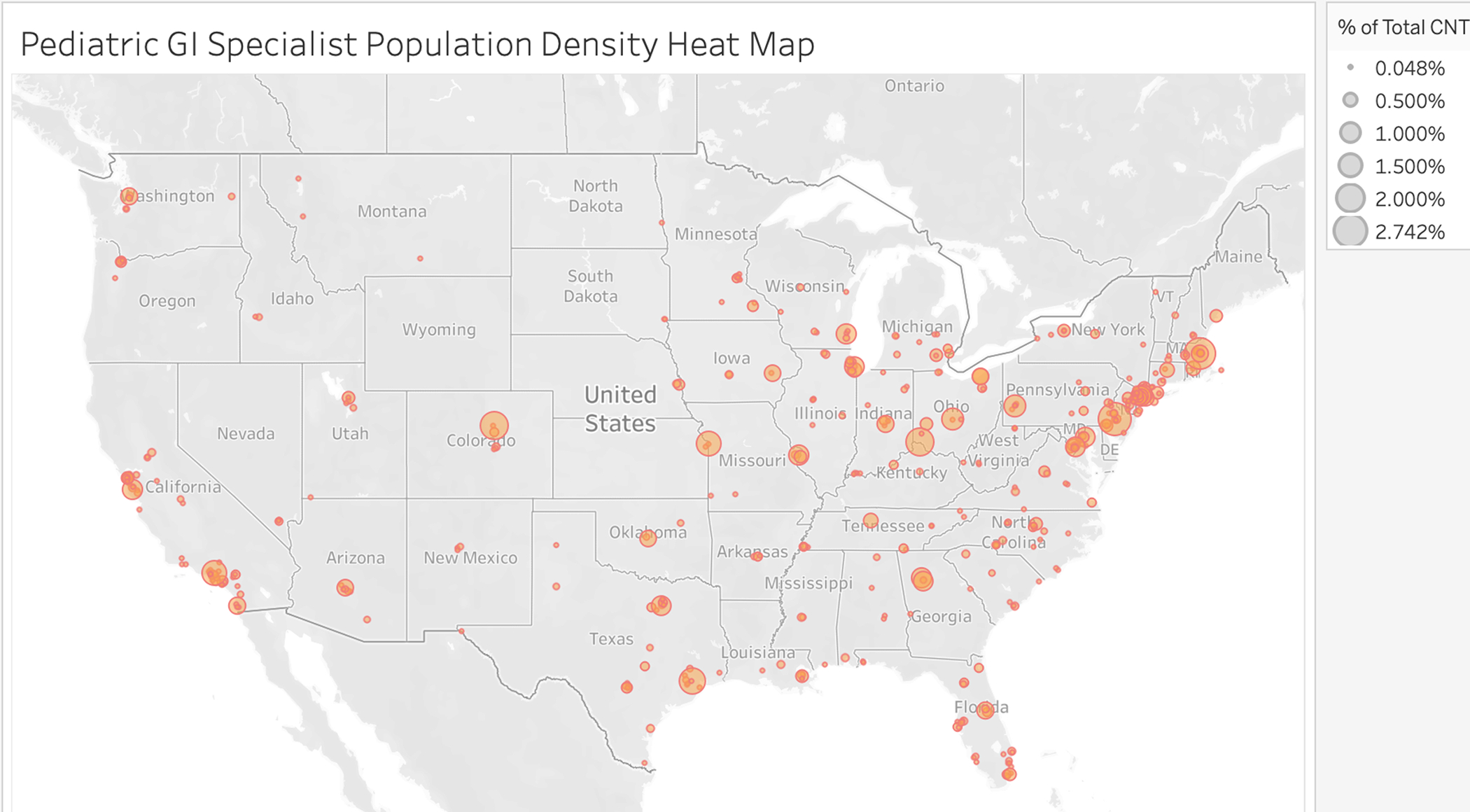

To receive a diagnosis of EoE, pediatric patients must 1) be referred to and be evaluated by a pediatric gastroenterologist and 2) undergo endoscopy with biopsies under anesthesia3. Thus, access to pediatric subspecialty care and a tertiary care center with anesthesia capabilities is a requisite for diagnosis. In an examination of the distribution of pediatric gastroenterologists in the United states obtained from the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (NASPGHAN) we found a dearth of pediatric GI care in rural areas of the county (Figure 1) and that most US pediatric GI practitioners were located in urban communities. We have further corroborated these data evaluating publicly available pediatric board association and population density evaluations (board certification: https://www.abp.org/content/us-map-pediatric-subspecialists-county, population density: https://eoimages.gsfc.nasa.gov/images/imagerecords/7000/7052/us_population_2005_lrg.jpg). Thus diminished prevalence may be a function of underdiagnosis due to decreased provider access.

Figure 1.

Heat map of pediatric gastroenterologists in the United States. Tableau Public software was used to create this heat map by translating zip codes of pediatric gastroenterologists with memberships to NASPGHAN in the United States into longitudinal and latitudinal geospatial coordinates. Small dots represents location and larger circles represent percent of total population in the country.

Although no studies to date have evaluated health care disparities or access to care issues in EoE, Benchimol et al studied this issue in patients with inflammatory bowel disease in rural vs. urban Canada4. They found that patients from rural Canada were less likely to seek care from a gastroenterologist and had increased rates of hospitalization and emergency department visits. Regarding asthma, limited access to care led to increased morbidity and mortality for rural asthmatic patients5. Moreover, over the last 10 years, a disproportionate number of rural hospitals have closed, diminishing access to subspecialty care6. Rather than travel to obtain medical care/testing, many patients have opted to forgo care. Compounding this problem are factors related to poverty within rural communities; families with incomes less than 200% of the federal poverty limit are reported in 47% of rural populations compared with 27% in urban populations5.

Although EoE has rapidly increased in incidence and prevalence over the past 2 decades, it is considered a rare disease. EoE publications are derived from urban tertiary pediatric centers, and thus our understanding of factors contributing to the development of EoE and analysis of its epidemiology are based on the assumption that there is equal care access. Because of the lack of access to pediatric subspecialists in rural communities, we should be cautious in our perceptions that EoE has decreased in prevalence in rural areas. Emphasis on increasing access to subspecialty care will benefit patients and permit better analysis of the epidemiology of pediatric EoE.

Acknowledgements:

The authors would like to thank the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition, and especially Margaret Stallings and Ronald Sokol, for assisting in evaluation of pediatric gastroenterologist locations of practice.

Footnotes

Sincerely,

Cameron Sabet, Department of Pediatrics, Division of Gastroenterology, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, PA

Amy Klion, MD Human Eosinophil Section, Laboratory of Parasitic Diseases, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD.

Dominique Bailey, MD, Division of Gastroenterology, Columbia University Iriving Medical Center, New York, NY

Elizabeth Jensen, PhD, Department of Epidemiology and Prevention, Wake Forest School of Medicine, UNC-CH, Chapel Hill, NC

Mirna Chehade, MD, Mount Sinai Center for Eosinophilic Disorders, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY

Pablo Abonia, MD, Division of Allergy and Immunology, Department of Pediatrics, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, OH

Marc Rothenberg, MD PhD, Division of Allergy, Immunology, Department of Pediatrics, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH

Glenn Furuta, MD Digestive Health Institute, Section of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition, Children’s Hospital Colorado, Gastrointestinal Eosinophilic Disease Program, Mucosal Inflammation Program, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora, CO

Amanda B. Muir, MD MSTR Department of Pediatrics, Division of Gastroenterology, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, PA

References

- 1.McGowan EC, Keller JP, Dellon ES, Peng R, Keet CA. Prevalence and geographic distribution of pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis in the 2012 US Medicaid population. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8(8):2796–2798.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.04.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jensen ET, Hoffman K, Shaheen NJ, Genta RM, Dellon ES. Esophageal eosinophilia is increased in rural areas with low population density: Results from a national pathology database. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109(5). doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dellon ES, Liacouras CA, Molina-Infante J, et al. Updated International Consensus Diagnostic Criteria for Eosinophilic Esophagitis: Proceedings of the AGREE Conference. In: Gastroenterology. Vol 155. W.B. Saunders; 2018:1022–1033.e10. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2018.07.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benchimol EI, Kuenzig ME, Bernstein CN, et al. Rural and urban disparities in the care of canadian patients with inflammatory bowel disease: A population-based study. Clin Epidemiol 2018;10. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S178056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Valet RS, Perry TT, Hartert TV. Rural health disparities in asthma care and outcomes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123(6). doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.12.1131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wishner J, Solleveld P, Rudowitz R, Paradise J, Antonisse L. LookA Look at Rural Hospital Closures and Implications for Access to Care: Three Case Studies; 2016.