Abstract

Background

Evidence for vaccine effectiveness (VE) against influenza-associated pneumonia has varied by season, location, and strain. We estimate VE against hospitalization for radiographically identified influenza-associated pneumonia during 2015–2016 to 2017–2018 seasons in the US Hospitalized Adult Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness Network (HAIVEN).

Methods

Among adults aged ≥18 years admitted to 10 US hospitals for acute respiratory illness (ARI), clinician-investigators used keywords from reports of chest imaging performed during 3 days around hospital admission to assign a diagnosis of “definite/probable pneumonia.” We used a test-negative design to estimate VE against hospitalization for radiographically identified laboratory-confirmed influenza-associated pneumonia, comparing reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction–confirmed influenza cases with test-negative subjects. Influenza vaccination status was documented in immunization records or self-reported, including date and location. Multivariable logistic regression models were used to adjust for age, site, season, calendar-time, and other factors.

Results

Of 4843 adults hospitalized with ARI included in the primary analysis, 266 (5.5%) had “definite/probable pneumonia” and confirmed influenza. Adjusted VE against hospitalization for any radiographically confirmed influenza-associated pneumonia was 38% (95% confidence interval [CI], 17–53%); by type/subtype, it was 74% (95% CI, 52–87%) influenza A (H1N1)pdm09, 25% (95% CI, −15% to 50%) A (H3N2), and 23% (95% CI, −32% to 54%) influenza B. Adjusted VE against intensive care for any influenza was 57% (95% CI, 19–77%).

Conclusions

Influenza vaccination was modestly effective among adults in preventing hospitalizations and the need for intensive care associated with influenza pneumonia. VE was significantly higher against A (H1N1)pdm09 and was low against A (H3N2) and B.

Keywords: test-negative, case-control study, pneumonia, hospitalization, influenza vaccine effectiveness

Vaccine effectiveness against adult acute respiratory illness hospitalization for radiographically identified laboratory confirmed influenza-associated pneumonia estimated using a test-negative design was 38% (95% confidence interval: 17-53%) during 2015-2016 to 2017-2018 in the US Hospitalized Adult Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness Network (HAIVEN).

Influenza-associated pneumonia is associated with severe complications similar to other causes of community-acquired pneumonia [1–4]. Even though some studies have shown influenza vaccine is effective against laboratory-confirmed pneumonia [5, 6], other studies indicate there is considerable heterogeneity in vaccine effectiveness (VE) [7–9]. In a large Italian retrospective cohort study based on health-related administrative data, during the 2016–2017 influenza season influenza vaccination did not result in lower emergency department visits, hospitalizations, or deaths due to influenza and pneumonia [7]. Nonsignificant effects related to VE across different regions and seasons led us to examine the VE against influenza-associated pneumonia [8, 9]. Using a different methodology (ratio-of-ratio analysis), a UK cohort study of electronic health records calculated an influenza VE of 7% (95% confidence interval [CI], 3–12%) against all community-acquired lower respiratory tract infections [10]. A recent review on the effects of influenza vaccine concluded that further studies are necessary to study the VE against laboratory-confirmed pneumonia due to increased vaccination rates and use of influenza antiviral medications [11]. Bramley et al [12] have shown the utility of keywords from impressions of chest radiograph reports to have moderate to almost perfect reliability to identify pneumonia among patients hospitalized with laboratory-confirmed influenza.

Our hypothesis was that establishing a pneumonia diagnosis by clinician-conducted review of chest imaging reports would improve the estimation of VE against laboratory-confirmed influenza-associated pneumonia. Using a test-negative design, our primary objective was to estimate the effectiveness of influenza vaccine against acute respiratory illness (ARI) hospitalizations for radiographically identified, laboratory-confirmed influenza-associated pneumonia among adults during the 2015–2016, 2016–2017, and 2017–2018 seasons in the US Hospitalized Adult Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness Network (HAIVEN). Secondary objectives included exploration of VE against severe clinical outcomes such as need for intensive care unit (ICU) admission, mechanical ventilation, and inpatient mortality in patients with influenza-associated pneumonia.

METHODS

The 4 US HAIVEN sites in Michigan, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, and Texas enrolled hospitalized adults (aged ≥18 years) with ARI who were screened for respiratory/systemic clinical syndromes/symptoms and/or exacerbation of chronic high-risk medical conditions and reported a new or worsening cough or sputum production. Details of the HAIVEN research enrollment interview and respiratory mucosal laboratory specimen collection procedures have been described previously [13]. Influenza vaccination status was determined by documented immunization records from the site electronic medical records, state immunization registries, and medical release of information from the subject’s primary care provider’s office or other vaccine providers such as retail pharmacies, or subject’s self-report, if a plausible date and location of vaccination were also provided. Eligible participants had a clinical and/or research respiratory laboratory specimen collected within 10 days of illness onset and 3 days of hospital admission. Influenza infection was confirmed by reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), including A subtyping and B lineage typing. Electronic health records were extracted to detect chronic high-risk medical conditions associated with complications of influenza such as asthma, heart disease, or diabetes and hospitalizations during the prior year and to detect clinical severity outcomes during the enrollment admission, such as admission to an ICU, need for mechanical ventilation, and death during the hospitalization.

Radiographically Identified Pneumonia Status

The Texas site clinical investigators (Drs Ghamande, White, Lat, Kirill Lipatov, Douglas Bretzing, and Gaglani) reviewed all available computed tomography (CT) and radiography (X-ray) reports of chest or abdomen (for lung bases) performed during 3 days around hospital admission for each site: from 1 day prior to date of admission up to 2 days after admission. A vast majority of chest imaging was performed on the day of or day after admission for all 4 sites. Imaging reports from Michigan, Tennessee, and Texas sites were available for review for 3 seasons from 2015–2016 to 2017–2018, and from the latter 2 seasons for the Pennsylvania site. Reports were available from 3 of 8 enrolling hospitals for 2015–2016, 4 of 9 hospitals for 2016–2017, and 7 of 10 hospitals for 2017–2018. Of 9433 subjects enrolled in HAIVEN at all 4 sites during the 3 seasons, this study included 7069 (74.9%) patients who were enrolled at a hospital where imaging reports were available per site and season (Supplementary Table 1). Of the 7069 patients, chest imaging reports were available and a pneumonia status was assigned for 6802 (96.2%) subjects. We excluded patients from each season who were enrolled in HAIVEN at a hospital where reports were not available (Supplementary Table 1). The Texas site clinical investigators used keywords from all available reports of chest imaging to assign a diagnosis of pneumonia. We first reviewed chest CT reports to adjudicate the final pneumonia status as “definite,” “probable,” or “definitely not” or a preliminary “possible” pneumonia status. If CT reports were unavailable or the preliminary assignment based on a CT report was for a “possible” pneumonia, then a chest X-ray report was used to assign the final pneumonia status (Supplementary Figure 1) [12, 14]. For the primary analysis, we estimated VE against “definite or probable pneumonia” (which will be referred to as pneumonia) associated with RT-PCR–confirmed influenza. Influenza cases with “possible pneumonia” were added in the sensitivity analysis to “definite/probable pneumonia” cases included in the primary analysis.

Statistical Analyses

We used a test-negative design to estimate VE against an ARI hospitalization for laboratory-confirmed influenza-associated pneumonia. Subjects hospitalized with ARI with radiographically identified “definite or probable” pneumonia who were RT-PCR positive for influenza within 10 days since illness onset were the “ARI hospitalized influenza-associated pneumonia cases.” Because subject enrollment in the HAIVEN study was based on an ARI case definition, we did not limit the test-negative control subjects with ARI by pneumonia status (ie, test-negative controls were ARI-hospitalized subjects who were negative for influenza by RT-PCR and included regardless of pneumonia status). We compared participant characteristics between the RT-PCR–confirmed influenza-associated “definite/probable pneumonia” cases with test-negative control subjects with ARI, and between those who were vaccinated versus unvaccinated. We used multivariable logistic regression models to compare influenza vaccination rates between influenza-positive pneumonia cases and test-negative subjects with ARI. We included potential confounding variables a priori: age in years, site, season, and tertiles of illness-onset calendar time (per site and season). Additionally, variables with a P value of less than .2 or odds ratio (OR) of greater than 1.2 or less than 0.8 for both univariate comparisons were considered for multivariate logistic regression. The fully adjusted model included a priori variables plus race/ethnicity, immunosuppression, presence of any high-risk condition, self-reported home oxygen use, and number of hospitalizations in the prior year. The VE was calculated as (1 − the adjusted OR) × 100%. After sequentially removing the variables that changed the VE by 2% or less, and tie-breaking with the lowest Akaike information criterion, the adjusted model included the a priori variables, home oxygen use, and number of hospitalizations in the prior year [15].

We estimated VE for all adults and for any influenza as well as predominant influenza A subtype and/or B lineage during each season using Firth’s adjustment because of small sample sizes in subgroup analyses [16]. We estimated the VE for age groups of 18–64 years and 65 years and older, including for the predominant influenza subtypes. For sensitivity analysis, we included the influenza cases with “possible pneumonia.” We also estimated VE against severe clinical outcomes of influenza-associated pneumonia such as need for ICU admission, and mechanical ventilation as well as inpatient death. We interpreted differences in VE estimates for subgroup analyses (ie, overall VE against influenza-associated pneumonia and that for the subsets of influenza types or A subtypes or subjects needing ICU admission), considering P values less than .05 as statistically significant based on simulations for interpreting interaction between 2 dichotomous variables when the effect size is expected to be moderate to high [17, 18].

RESULTS

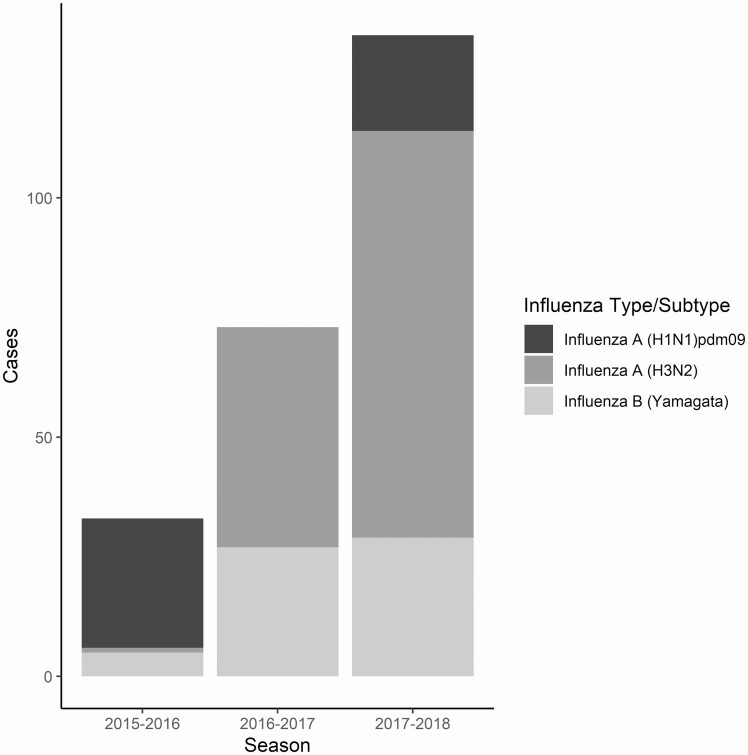

Of 7069 subjects enrolled in this study, we included 4843 (68.5%) in the primary analysis (777 in 2015–2016, 1934 in 2016–2017, and 2132 in 2017–2018) (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). Figure 1 shows that the 2017–2018 season had the most influenza cases and 2015–2016 the least among the 3 seasons. Influenza A (H1N1)pdm09 was predominant during 2015–2016 and circulated in 2017–2018, A (H3N2) was predominant in 2016–2017 and 2017–2018, and influenza B/Yamagata circulated during all 3 seasons.

Figure 1.

Influenza-associated pneumonia cases by predominant A subtype and B lineage (N = 251 of a total of 266 cases) in US HAIVEN during 2015–2016 to 2017–2018 seasons. Influenza cases were radiographically identified “definite/probable pneumonia” confirmed for influenza by clinical/research single-plex or multiplex RT-PCR. Abbreviations: RT-PCR, reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction; US HAIVEN, US Hospitalized Adult Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness Network.

Of 4843 inpatients with ARI in the primary analysis, 266 (5.5%) were RT-PCR–confirmed influenza “cases” who had radiographically identified “definite/probable pneumonia” (referred to as pneumonia) and 4577 were test-negative subjects with ARI regardless of pneumonia status (Table 1). Chest CT reports were available in 93 (34.5%) of 266 influenza-positive pneumonia cases and 1188 (26.1%) of 4559 test-negative subjects with ARI (P = .001). Influenza pneumonia cases were more likely to be aged 75 years or older (77 [28.9%]) than hospitalized ARI test-negative controls (983 [21.5%]) (Table 1). Enrollment was greatest during the season of 2017–2018. There were no differences in prior season vaccination status between pneumonia cases (113 [42.5%]) and influenza-negative subjects with ARI (2053 [44.9%]) (OR, 0.9; P = .45). Over half of the subjects were enrolled within 3 days of illness onset, and a majority had 3 or more high-risk medical conditions, including 229 (86.1%) influenza-positive pneumonia cases versus 3973 (86.8%) test-negative subjects with ARI. High-risk medical condition categories, including immunosuppression, were similar among cases and influenza-negative subjects with ARI, but self-reported hospitalizations in the prior year and home oxygen use were less common in influenza-associated pneumonia cases. Higher proportions of subjects were vaccinated against influenza if vaccinated during the prior season (OR, 9.3; P < .001) and in the presence of any high-risk medical condition (OR, 3.0; P < .001) (Table 1). Chest CT reports were available in 931 (25.4%) of 3667 vaccinated and 350 (30.2%) of 1158 unvaccinated subjects (P = .001).

Table 1.

Comparisons of Subject Characteristics in Adults Hospitalized With Acute Respiratory Illness Including Influenza-Associated Pneumonia Cases and Test-Negative Controls: US HAIVEN 2015–2016 to 2017–2018

| Influenza-Positive ARI Pneumonia Cases (n = 266) | Test-Negative Control ARI Subjectsa (n = 4577) | Odds Ratio (P)b |

Influenza-Vaccinated (n = 3679) | Not Vaccinated (n = 1164) | Odds Ratio (P) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age in yearsc | 1.1 (P = .01) | 1.3 (P < .001) | ||||

| 18–49 | 52 (19.5) | 1083 (23.6) | 727 (19.8) | 408 (35.1) | ||

| 50–64 | 75 (28.2) | 1467 (32.1) | 1110 (30.2) | 432 (37.2) | ||

| 65–74 | 62 (23.3) | 1044 (22.8) | 894 (24.3) | 212 (18.2) | ||

| ≥75 | 77 (28.9) | 983 (21.5) | 948 (25.8) | 112 (9.6) | ||

| Sex | 0.9 (P = .21) | 1.0 (P = .73) | ||||

| Male (reference) | 127 (47.7) | 2007 (43.9) | 1616 (43.9) | 518 (44.5) | ||

| Female | 139 (52.2) | 2570 (56.2) | 2063 (56.1) | 646 (54.5) | ||

| Race/ethnicity | P = .12 | P < .001 | ||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 199 (74.8) | 3372 (73.7) | 0.8 (P = .49) | 2800 (76.1) | 771 (66.2) | 1.2 (P < .001) |

| Black, non-Hispanic(reference) | 7 (2.6) | 96 (2.1) | 78 (2.1) | 25 (2.2) | ||

| Other, non-Hispanic | 37 (13.9) | 831(18.2) | 0.6 (P = .03) | 594 (16.2) | 274 (23.5) | 0.7 (P = .01) |

| Hispanic, any race | 23 (8.7) | 278 (6.1) | 1.1 (P = .17) | 207 (5.6) | 94 (8.1) | 0.7 (P = .05) |

| Season | P = .006 | P < .001 | ||||

| 2015–2016 | 33 (12.4) | 744 (16.3) | 0.6 (P = .16) | 588 (16.0) | 189 (16.2) | 1.2 (P = .68) |

| 2016–2017 | 85 (32.0) | 1849(40.4) | 0.6 (P = .12) | 1537 (41.8) | 397 (34.1) | 1.5 (P < .001) |

| 2017–2018 (reference) | 148 (55.6) | 1984 (43.4) | 1554 (42.2) | 578 (49.7) | ||

| Site | P = .02 | P < .001 | ||||

| Michigan | 60 (22.6) | 769 (16.8) | 1.2 (P = .01) | 693 (18.8) | 136 (11.7) | 1.8 (P < .001) |

| Pennsylvania | 61 (22.9) | 1330 (29.1) | 0.8 (P = .04) | 1073 (29.2) | 318 (27.3) | 1.2 (P = .73) |

| Tennessee | 46 (17.3) | 939 (20.5) | 0.8 (P = .19) | 697 (18.9) | 288 (24.7) | 0.8 (P < .001) |

| Texas (reference) | 99 (37.2) | 1539 (33.6) | 1216 (33.1) | 422 (36.3) | ||

| Influenza vaccinated during previous season | 113 (42.5) | 2053 (44.9) | 0.9 (P = .45) | 2030 (55.2) | 136 (11.7) | 9.3 (P < .001) |

| Days from illness onset to enrollment | P = .76 | P = .08 | ||||

| 0–3 (reference) | 135 (50.8) | 2354 (51.4) | 1924 (52.3) | 565 (48.5) | ||

| 4–6 | 76 (28.6) | 1220 (26.7) | 1.1 (P = .46) | 966 (26.3) | 330 (28.4) | 0.9 (P = .32) |

| 7–10 | 55 (20.7) | 1003 (21.9) | 1.0 (P = .60) | 789 (21.5) | 269 (23.1) | 0.9 (P = .36) |

| Presence of any high-risk medical conditiond | 257 (97.4) | 4477 (98.4) | 0.6 (P = .2) | 3628 (98.9) | 1106 (96.6) | 3.0 (P < .001) |

| Number of high-risk medical condition(s) | P = .33 | P < .001 | ||||

| None (reference) | 9 (3.4) | 98 (2.1) | 50 (1.4) | 57 (4.9) | ||

| 1–2 | 28 (10.5) | 506 (11.1) | 0.6 (P = .28) | 323 (8.8) | 211 (18.1) | 1.7 (P = .22) |

| ≥3 | 229 (86.1) | 3973 (86.8) | 0.6 (P = .24) | 3306 (89.9) | 896 (77.0) | 4.2 (P < .001) |

| High-risk medical condition categories | ||||||

| Diabetes, obesity and other metabolic or endocrine | 212 (79.7) | 3537 (77.3) | 1.2 (P = .38) | 2957 (80.4) | 792 (68.0) | 1.9 (P < .001) |

| Asthma/COPD/other lung conditions | 191 (71.8) | 3409 (74.5) | 0.9 (P = .32) | 2804 (76.2) | 796 (68.4) | 1.5 (P < .001) |

| Neurological or musculoskeletal or cerebrovascular | 114 (42.9) | 1915 (41.8) | 1.0 (P = 0.74) | 1619 (44.0) | 410 (35.2) | 1.4(P < 0.001) |

| Renal disease | 132 (49.6) | 2121 (46.3) | 1.1 (P = .30) | 1829 (49.7) | 424 (36.4) | 1.7 (P < .001) |

| Blood disorders | 43 (16.2) | 722 (15.8) | 1.0 (P = .82) | 586 (15.9) | 179 (15.4) | 1.0 (P = .67) |

| Immunosuppression | 87 (32.7) | 1724 (37.7) | 0.8 (P = .11) | 1437 (39.1) | 374 (32.1) | 1.4 (P < .001) |

| Malignancy | 82 (30.8) | 1423 (31.1) | 1.0 (P = .95) | 1186 (32.2) | 319 (27.4) | 1.3 (P = .002) |

| Liver disease | 39 (14.7) | 684 (14.9) | 1.0 (P = .94) | 543 (14.8) | 180 (15.5) | 0.9 (P = .55) |

| Long-term medications | 111 (41.7) | 1919 (41.9) | 1.0 (P = .96) | 1641 (44.6) | 389 (33.4) | 1.6 (P < .001) |

| Number of self-reported hospitalizations prior yeare | P < .001 | P < .001 | ||||

| None (reference) | 128 (49.6) | 1546 (34.3) | 1188 (32.9) | 486 (42.1) | ||

| 1–3 | 107 (41.8) | 1904 (42.3) | 0.7 (P = .07) | 1561 (43.2) | 450 (38.9) | 1.4 (P = .11) |

| ≥4 | 23 (8.9) | 1057 (23.5) | 0.3 (P < .001) | 861 (23.9) | 219 (19.0) | 1.6 (P < .001) |

| Self-reported home oxygen usef | 39 (14.7) | 1075 (23.5) | 0.6 (P = .001) | 932 (25.4) | 182 (15.7) | 1.8 (P < .001) |

| Influenza vaccination statusg | 0.6 (P < .001) | |||||

| Unvaccinated (reference) | 87 (32.7) | 1077 (23.5) | ||||

| Vaccinated | 179 (67.3) | 3500 (76.5) | ||||

| Influenza infection | ||||||

| Influenza A | 186 (69.9) | 123 (68.7) | 63 (72.4) | |||

| Influenza A (H3N2) | 132 (49.6) | 97 (54.2) | 35 (40.2) | |||

| Influenza A (H1N1)pdm09 | 47 (17.7) | 20 (11.2) | 27 (31.0) | |||

| Influenza A unsubtypeable | 7 (2.6) | 6 (3.4) | 1 (1.2) | |||

| Influenza B | 78 (29.3) | 56 (31.3) | 22 (25.3) | |||

| Influenza B (Yamagata) | 61 (22.9) | 42 (23.5) | 19 (21.8) | |||

| Influenza B (Victoria) | 2 (0.8) | 2 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | |||

| Influenza B undelineated | 15 (5.6) | 12 (6.7) | 3 (3.5) | |||

| Coinfection, influenza A and Bh | 2 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.3) |

Influenza cases were radiographically identified “definite/probable pneumonia” confirmed for influenza by clinical/research single-plex or multiplex RT-PCR.

Abbreviations: ARI, acute respiratory illness; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; RT-PCR, reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction; US HAIVEN, US Hospitalized Adult Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness Network.

aTest-negative ARI control subjects regardless of radiographically identified pneumonia status.

bOdds ratios were calculated using univariate logistic regression models; P values were calculated using chi-square or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous variables.

cAge in the model is continuous and the odds ratio is based on a 10-unit change.

dAny high-risk medical condition (28 missing).

eNumber of self-reported hospitalizations prior year (78 missing).

fSelf-reported home oxygen use (9 missing).

gDocumented influenza vaccination or self-reported with plausible date and location.

hThe coinfections were Flu A(H1N1)pdm09/Flu B (Yamagata) and Flu A(H3N2)/Flu A(H1N1)pdm09.

Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness Against Radiographically Identified RT-PCR–Confirmed Pneumonia

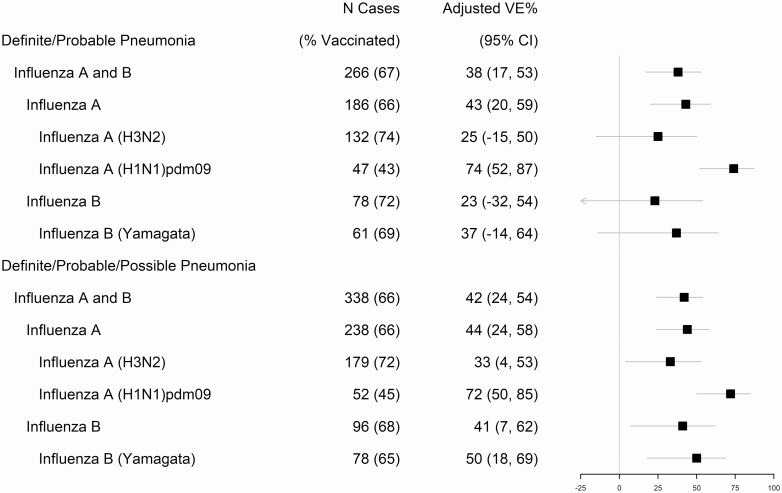

The adjusted VE against adult ARI hospitalization for RT-PCR–confirmed influenza-associated pneumonia from 2015–2016 through 2017–2018 was 38% (95% CI, 17–53%) (Figure 2). The frequency of documented or self-reported vaccination with a plausible date and location was less common in influenza-associated pneumonia cases than in test-negative subjects with ARI (179 [67.3%] vs 3500 [76.5%], respectively; OR, 0.6; P < .001) (Table 1). Influenza A infection was predominant in pneumonia cases (186 [69.9%]) and the most common subtype was A (H3N2), which was detected in 132 (49.6%) cases (Table 1). Vaccine effectiveness among adults of all ages against influenza A–associated pneumonia was 43% (95% CI, 20–59%) (P < .001 for interaction term with overall VE). Effectiveness was higher for influenza A (H1N1)pdm09 at 74% (95% CI, 52–87%) (P < .0001 for interaction term with overall VE), as compared with A (H3N2) (25% [95% CI, −15% to 50%]) (P = .17 for interaction term with overall VE), and influenza B–associated pneumonia (23% [95% CI, −32% to 54%]) (P = .31 for interaction term with overall VE) (Figure 2 and Supplementary Table 3). The fully adjusted VE point estimates were 5% or less different as compared with those for adjusted analyses (Supplementary Table 3).

Figure 2.

Adjusted vaccine effectiveness against hospitalizations for acute respiratory illness with influenza-associated pneumonia in adults aged ≥18 years: US HAIVEN, 2015–2016 to 2017–2018. Influenza cases were radiographically identified “definite/probable pneumonia” confirmed for influenza by clinical/research single-plex or multiplex RT-PCR. Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; RT-PCR, reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction; US HAIVEN, US Hospitalized Adult Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness Network; VE, vaccine effectiveness.

We performed sensitivity analysis by including influenza cases with “possible pneumonia” in addition to “definite/probable pneumonia” (Figure 2 and Supplementary Table 3). The VE point estimates were overall similar (eg, 42% in the sensitivity vs 38% in the primary analysis for any influenza-associated pneumonia) but were relatively higher and significant against influenza A (H3N2) at 33% (95% CI, 4–53%), any influenza B at 41% (95% CI, 7–62%), and 50% (95% CI, 18–69%) for B/Yamagata-associated pneumonia.

Vaccine Effectiveness Against Clinical Outcomes of Laboratory-Confirmed Influenza-Associated Pneumonia

Influenza-associated pneumonia cases required more invasive or noninvasive mechanical ventilation than test-negative subjects with ARI (61 [22.9%] vs. 731 [16.0%], respectively; P = .003) (Supplementary Table 4). Mortality during hospitalization was higher in patients with influenza-associated pneumonia at 14 (5.3%) compared with test-negative subjects with ARI at 94 (2.1%) (P = .001) (Supplementary Table 4). In the adjusted model, VE against ICU admission for all adults against any influenza-associated pneumonia was 57% (95% CI, 19–77%) (P = .69 for interaction term with overall VE). Adjusted VE against mechanical ventilation (invasive or noninvasive) was 36% (95% CI, −24% to 66%) and nonsignificant (Table 2). The sample size of cases was insufficient to determine VE against inpatient death (n = 14).

Table 2.

Vaccine Effectiveness Against Clinical Outcomes of Influenza-Associated Pneumonia: US HAIVEN 2015–2016 to 2017–2018

| ARI/Pneumonia/Influenza and Vaccination Status |

Vaccine Effectivenessa | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Influenza-Positive ARI Pneumonia Cases, No. Vaccinated/Total (%) | Test-Negative Control ARI Subjectsb No. Vaccinated/Total (%) |

Unadjusted VE% (95% CI) |

Adjusted VE% (95% CI) |

Fully Adjusted VE% (95% CI) |

|

| ICU admission for any influenza-associated pneumonia | |||||

| All ages | 26/50 (52.0) | 478/671 (71.2) | 56 (22–75) | 57 (19–77) | 57 (18–77) |

| Mechanical ventilation (invasivec or noninvasive) for any influenza-associated pneumonia | |||||

| All ages | 42/61 (68.9) | 577/731 (78.9) | 42 (−5 to 66) | 36 (−24 to 66) | 38 (−20 to 67) |

| Inpatient death for any influenza-associated pneumonia | |||||

| All ages | 6/14 (42.9) | 66/94 (70.2) | 67 (8–90) | NR | NR |

Influenza cases were radiographically identified “definite/probable pneumonia” confirmed for influenza by clinical/research single-plex or multiplex RT-PCR.

Abbreviations: ARI, acute respiratory illness; CI, confidence interval; ICU, intensive care unit; NR, not reported; RT-PCR, reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction; US HAIVEN, US Hospitalized Adult Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness Network; VE, vaccine effectiveness.

aFully adjusted model includes a priori variables (age in years, site, season, and tertiles of illness-onset calendar time), race/ethnicity, immunosuppression, any high-risk condition, self-reported home oxygen use, and number of hospitalizations in the prior year. The adjusted model includes a priori variables, self-reported home oxygen use, and number of hospitalizations in the prior year.

bTest-negative ARI subjects, regardless of radiographically identified pneumonia status.

cThe 2015–2016 season was excluded because of the inability to identify invasive mechanical ventilation.

Discussion

In this US HAIVEN study across 3 seasons from 2015–2018, we analyzed subjects hospitalized for ARI and found a VE of 38% (95% CI, 17–53%) against radiographically identified RT-PCR–confirmed influenza-associated pneumonia. Our analysis of 266 influenza-associated pneumonia cases represents a relatively large sample of patients with radiographically identified and RT-PCR–confirmed influenza-associated pneumonia in comparison with prior publications by Grijalva et al [5] with 162 cases and Chow et al [19] with 79 cases. Robust case definitions were used for prospectively enrolling test-negative adults with ARI including influenza-positive cases with radiographically identified pneumonia along with vaccination verification processes, which increases the confidence in our results. Also, we assessed chest CT scan reports first before chest X-ray reports for radiographic findings of pneumonia. Additionally, we found VE against the need for ICU admission for influenza-associated pneumonia. This finding strengthens the rationale for annual influenza vaccination to prevent complications.

The VE against influenza-associated pneumonia of 38% (95% CI, 17–53%) in our study is similar to the overall VE of 31% (95% CI, 26–37%) among outpatients and 36% (95% CI, 27–44%) among inpatients from 2015–2018 in the combined outpatient and inpatient influenza network settings in the United States [20]. Overall, our finding of a VE against hospitalization for influenza-associated pneumonia similar to medically attended outpatient influenza along with a robust VE against ICU admission for influenza-associated pneumonia indicates that the vaccine is not only preventing upper respiratory illness but also lower respiratory disease to a similar extent. This lends additional support to efforts for improving the annual influenza immunization program in the United States. The VE against influenza-associated pneumonia during 2015–2018 is lower than the overall VE against influenza-associated ARI hospitalizations reported for the 2015–2016 season of 47% (95% CI, 27–62%) in the inpatient HAIVEN network [13]. Of note is the substantially lower VE against influenza A (H3N2), which is generally associated with more severe disease in older adults [3], and the low VE against influenza B–associated hospitalized pneumonia as compared with A(H1N1)pdm09. When we included patients with “possible pneumonia” in addition to “definite/probable pneumonia,” VE against influenza A (H3N2), B, and B/Yamagata improved modestly. The preponderance of A (H3N2)–associated pneumonia was in the 2017–2018 season in our study. Vaccine effectiveness against A (H3N2) has shown to be consistently lower than A (H1N1)pdm09 due to several postulated reasons, including antigenic evolution of the virus, increasing glycosylation at antigenic site B, and host immune responses [21, 22].

The assessment of VE against pneumonia is fraught with considerable heterogeneity in methodology, shifts in circulating influenza A subtypes and B lineages, and sample size in the medical literature. Design and outcomes in our study are most comparable to 3 other VE studies [5, 6, 19]. Grijalva et al [5] reported a VE of 56.7% in children and adults during the 2009–2012 influenza seasons with 162 influenza-associated pneumonia cases, of whom only 17% had received influenza vaccination. Elderly patients were underrepresented in the Grijalva et al study. Similar to our study, the VE against A (H3N2)–associated pneumonia was low at 27% (95% CI, −46% to 64%). In a Japanese study that used the test-negative design spanning 2012 to 2014 involving 42 patients with laboratory-confirmed influenza-associated pneumonia, the VE against any influenza pneumonia hospital admission was 60.2% (95% CI, 22.8–79.4%) [6]. This study included only adults aged 65 years or older, suggesting that older patients benefited more from the vaccine. A recent study from Louisville, Kentucky, reported a VE more similar to our findings of 35% (95% CI, 4–56%) against influenza-associated lower respiratory tract illness [19]. Influenza-associated, radiographically identified pneumonia was present in 79 patients, and the VE was 51% (95% CI, 13–72%). Some studies have reported low or absent VE against influenza-associated pneumonia [7–10]. Other studies have looked at risk reduction in severe outcomes and pneumonia among patients hospitalized with laboratory-confirmed influenza without directly comparing vaccine protection using a test-negative control group [8, 21, 23].

Influenza pneumonia can be associated with significant morbidity and mortality [1–3]. It may be useful to see whether vaccination attenuates some disease manifestations, such as pneumonia, and reduces complications of infection in addition to hospital admission. We found a significant VE of 57% against ICU admission for influenza-associated pneumonia but did not have sufficient power to detect a significant VE against mechanical ventilation or inpatient death. Studies have shown mixed results for influenza VE against clinical outcomes of hospitalization. Studies of VE against influenza pneumonia with analyses of severity of illness measures include one from New Zealand (reduced ICU admission and ICU length of stay), 2 Spanish studies (both with reduced ICU admission/mortality), a French study (reduced ICU admission only) and 1 from the FluSurv-NET study (reduced ICU admission, mortality, and length of stay) [8, 23–26]. On the other hand, a prior FluSurv-NET study as well as a large Italian cohort study failed to show effectiveness against inpatient outcomes [7, 21].

The limitations of our study include an observational test-negative design, but we adjusted for potential confounders to minimize bias in estimating the VE against influenza-associated pneumonia. However, residual confounding is always possible [27]. We were unable to obtain radiographic imaging reports from all HAIVEN-enrolling hospitals during each season, but 75% of all enrolled patients during the 3 seasons were enrolled at a hospital where reports were available. We did include a sensitivity analysis adding in influenza cases with radiology reports of “possible pneumonia” to those with “definite/probable pneumonia” around 3 days of hospital admission. We did not analyze bacterial cultures to diagnose secondary bacterial pneumonias complicating the hospital stay and outcomes, but the primary purpose of our analysis was to estimate VE against ARI hospitalizations for radiographically identified, laboratory-confirmed influenza-associated pneumonia.

In conclusion, our large US HAIVEN study from 2015–2018 confirmed 38% VE against adult ARI hospitalization for influenza-associated pneumonia overall, with variable effectiveness by virus subtype and lineage. Vaccine effectiveness was higher against influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 compared with A (H3N2) and B. Additionally, we showed the vaccine protected against ICU admission from influenza-associated pneumonia. While vaccination provided modest protection against influenza-associated pneumonia, substantially more severe disease could have been prevented during 2015–2018. Strategic improvements in vaccine design to increase the durability and breadth of immune responses could strengthen the attenuating effects of influenza vaccines and lead to sizeable public health gains towards preventing the burden of severe ARI.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Clinical Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Acknowledgments. The authors acknowledge the following individuals—Baylor Scott and White, Texas: Meredith Tanner, Victor Escobedo, Kelsey Bounds, Lydia Clipper, Anne Robertson, Teresa O’Quinn, Wencong Chen, Kirill Lipatov, Douglas Bretzing, Tresa McNeal, Kevin Chang, Justin Paradeza, Arundhati Rao, Manohar Mutnal, Kimberly Walker, Marcus Volz, Martha Zayed, Laurel Kilpatrick, Natalie Settele, Jennifer Thomas, Jaime Walkowiak, Madhava Beeram; Vanderbilt University Medical Center: Natasha Halasa, Stephanie Longmire, Erin Zipperer, Rendie McHenry, G. Seibert Tregoning, Kristen Davidson, Cathy Shell, Reiner Venegas, Iona Simion, Hollie Horton, Jan Orga, Ian Hodge, Jennifer Patrick, Emily Sedillo; University of Michigan and Henry Ford Health System: Joshua G. Petrie, Lois E. Lamerato, Adam Lauring, Ryan E. Malosh, E. J. McSpadden, Hannah Segaloff, Caroline Cheng, Rachel Truscon, Emileigh Johnson, Amy Callear, Anne Kaniclides, Richard Evans, Maura Nicholson, Nishat Islam, Michelle Groesbeck, Andrew Miller, Evelina Kutyma, Chasity Moore, Kaitlyn Digna, Elizabeth Alleman, Sarah Bauer, Marlisa Granderson, Kimberly Berke, Mackenzie Smith, Amanda Cyrus, Heather Lipkovich, Alana Johnson, Jayla Jackson; University of Pittsburgh and University of Pittsburgh Medical Center: Sean Saul, Michael Susick, John V. Williams, Kailey Hughes, Heather Eng, Theresa Sax, Julie Paronish, Balasubramani Goundappa, Mary Patricia Nowalk, Charles Rinaldo Jr, Arlene Bullota, Lori Steiffel, Diana Pakstis, Monika Johnson; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Samantha M. Olson.

Disclaimer. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, or the National Institutes of Health.

Financial support. This work was supported by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention under Cooperative Agreement IP15–002, including U01IP000979 at the Tennessee site, U01IP000974 at the Michigan site, U01IP000972 at the Texas site, and U01IP000969 at the Pennsylvania site. This study was also funded in part at the Pennsylvania site by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) program, grant number UL1 TR001857. At Vanderbilt, this project was also supported by CTSA award number UL1 TR002243 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. M. G., H. W., S. G., and T. L. report funding from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC HAIVEN study).

Potential conflicts of interest. R. K. Z. reports grants from Sanofi Pasteur (expired but within 3 years), outside the submitted work. D. B. M. reports personal fees from Seqirus for speaking; grants and personal fees from Pfizer for education research, speaking, and advisory role; personal fees from Sanofi Pasteur for advisory role; personal fees from GlaxoSmithKline for advisory role; personal fees from Moderna for advisory role; personal fees from Dynavax for advisory role; and personal fees from Bavarian Nordic for advisory role, all outside the submitted work. J. M. F. reports nonfinancial travel support from the Institute for Influenza Epidemiology (funded in part by Sanofi Pasteur), outside the submitted work. M. G. reports grants from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US Flu VE Network), outside the submitted work. A. S. M. reports personal fees from Sanofi and Seqirus for ad hoc consultancy, outside the submitted work. E. T. M. reports personal fees from Pfizer and grants from Merck, outside the submitted work. All other authors report no potential conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. Reed C, Chaves SS, Perez A, et al. . Complications among adults hospitalized with influenza: a comparison of seasonal influenza and the 2009 H1N1 pandemic. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 59:166–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Minchole E, Figueredo AL, Omeñaca M, et al. . Seasonal influenza A H1N1pdm09 virus and severe outcomes: a reason for broader vaccination in non-elderly, at-risk people. PLoS One 2016; 11:e0165711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Shah NS, Greenberg JA, McNulty MC, et al. . Severe influenza in 33 US hospitals, 2013-2014: complications and risk factors for death in 507 patients. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2015; 36:1251–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Abelleira R, Ruano-Ravina A, Lama A, et al. . Influenza A H1N1 community-acquired pneumonia: characteristics and risk factors-a case-control study. Can Respir J 2019; 2019:4301039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Grijalva CG, Zhu Y, Williams DJ, et al. . Association between hospitalization with community-acquired laboratory-confirmed influenza pneumonia and prior receipt of influenza vaccination. JAMA 2015; 314:1488–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Suzuki M, Katsurada N, Le MN, et al. . Effectiveness of inactivated influenza vaccine against laboratory-confirmed influenza pneumonia among adults aged ≥65 years in Japan. Vaccine 2018; 36:2960–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Valent F, Gallo T. Influenza vaccine effectiveness in an Italian elderly population during the 2016–2017 season. Ann Ist Super Sanita 2018; 54:67–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Arriola C, Garg S, Anderson EJ, et al. . Influenza vaccination modifies disease severity among community-dwelling adults hospitalized with influenza. Clin Infect Dis 2017; 65:1289–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chandler T, Furmanek SP, English CL, et al. . Effectiveness of the influenza vaccine in preventing hospitalizations of patients with influenza community-acquired pneumonia. Univ Louisville J Respir Infect 2018; 2:6. [Google Scholar]

- 10. McDonald HI, Thomas SL, Millett ERC, Quint J, Nitsch D. Do influenza and pneumococcal vaccines prevent community-acquired respiratory infections among older people with diabetes and does this vary by chronic kidney disease? A cohort study using electronic health records. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care 2017; 5:e000332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Heo JY, Song JY, Noh JY, et al. . Effects of influenza immunization on pneumonia in the elderly. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2018; 14:744–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bramley AM, Chaves SS, Dawood FS, et al. . Utility of keywords from chest radiograph reports for pneumonia surveillance among hospitalized patients with influenza: the CDC Influenza Hospitalization Surveillance Network, 2008–2009. Public Health Rep 2016; 131:483–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ferdinands JM, Gaglani M, Martin ET, et al. . Prevention of influenza hospitalization among adults in the United States, 2015–2016: results from the US Hospitalized Adult Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness Network (HAIVEN). J Infect Dis 2019; 220:1265–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kloth C, Forler S, Gatidis S, et al. . Comparison of chest-CT findings of influenza virus-associated pneumonia in immunocompetent vs. immunocompromised patients. Eur J Radiol 2015; 84:1177–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sarkar SK, Midi H, Rana S. Model selection in logistic regression and performance of its predictive ability. Aust J Basic Appl Sci 2010; 4:5813–22. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wang X. Firth logistic regression for rare variant association tests. Front Genet 2014; 5:187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Durand CP. Does raising type 1 error rate improve power to detect interactions in linear regression models? a simulation study. PLoS One 2013; 8:e71079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Marshall SW. Power for tests of interaction: effect of raising the type I error rate. Epidemiol Perspect Innov 2007; 4:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chow EJ, Rolfes MA, Carrico RL, et al. . Vaccine effectiveness against influenza-associated lower respiratory tract infections in hospitalized adults, Louisville, Kentucky, 2010–2013. Open Forum Infect Dis 2020; 7:ofaa262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tenforde MW, Chung J, Smith ER, et al. . Influenza vaccine effectiveness in inpatient and outpatient settings in the United States, 2015–2018. Clin Infect Dis 2021; 73:386–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Arriola CS, Anderson EJ, Baumbach J, et al. . Does influenza vaccination modify influenza severity? Data on older adults hospitalized with influenza during the 2012−2013 season in the United States. J Infect Dis 2015; 212:1200–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Belongia EA, McLean HQ. Influenza vaccine effectiveness: defining the H3N2 problem. Clin Infect Dis 2019; 69:1817–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Casado I, Domínguez A, Toledo D, et al. ; Project Pi12/2079 Working Group. Effect of influenza vaccination on the prognosis of hospitalized influenza patients. Expert Rev Vaccines 2016; 15:425–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Thompson MG, Pierse N, Huang QS, et al. . Influenza vaccine effectiveness in preventing influenza-associated intensive care admissions and attenuating severe disease among adults in New Zealand 2012–2015. Vaccine 2018; 36:5916–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Godoy P, Romero A, Soldevila N, et al. . The working group on surveillance of severe influenza hospitalized cases in Catalonia. Influenza vaccine effectiveness in reducing severe outcomes over six influenza seasons, a case-case analysis, Spain, 2010/11 to 2015/16. Euro Surveill 2018; 23(43):1700732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Loubet P, Samih-Lenzi N, Galtier F, et al. ; FLUVAC Study Group. Factors associated with poor outcomes among adults hospitalized for influenza in France: a three-year prospective multicenter study. J Clin Virol 2016; 79:68–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Foppa IM, Ferdinands JM, Chaves SS, et al. . The case test-negative design for studies of the effectiveness of influenza vaccine in inpatient settings. Int J Epidemiol 2016; 45:2052–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.