Abstract

Acute liver failure (ALF), characterized by the quick occurrence of disorder in liver, is a serious liver injury with extremely high mortality. Therefore, we investigated whether diallyl trisulfide (DATS), a natural product from garlic, protected against ALF in mice and studied underlying mechanisms. In the present study, lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (10 μg·kg−1)/D-galactosamine (D-gal) (500 mg·kg−1) was intraperitoneally injected to ICR mice to induce ALF. The mice were orally administered 20-, 40-, or 80-mg·kg−1 DATS) 1 h before LPS/D-gal exposure. Serum biochemical analyses and pathological study found that DATS pretreatment effectively prevented the ALF in LPS/D-gal-treated mice. Mechanistically, pretreatment of DATS inhibited the increase of the numbers of CD11b+ Kupffer cells and other macrophages in the liver, the release of tumor necrosis factor-α into the blood, and Caspase-1 activation induced by LPS/D-gal treatment in mice. Furthermore, DATS inhibited the activation of Caspase-3, downregulation of Bcl-2/Bax ratio, and increase of TUNEL positive staining. Altogether, our findings suggest that DATS exhibits hepatoprotective effects against ALF elicited by LPS/D-gal challenge, which probably associated with anti-inflammation and anti-apoptosis.

Keywords: diallyl trisulfide, acute liver failure, lipopolysaccharide, D-galactosamine, apoptosis, inflammation

1. Introduction

Acute liver failure (ALF) is considered being a complex fatal liver injury with many clinical manifestations.1,2 ALF is characterized by the rapid occurrence of dysfunction in liver. The most effective treatment to ALF is liver transplantation. However, ALF still has high mortality and poor prognosis because of lack donor livers and immunosuppressive therapy.3,4 Therefore, it is very essential to prevent or inhibit the development of ALF by seeking efficient intervention factors, especially natural chemicals.

Garlic has shown multi-pharmacological efficiency, containing anti-inflammation, antioxidant, tumor inhibition, etc.5,6 Chemical analyses have revealed that the effective components in garlic include more than 30 organic sulfur compounds (OSCs).7 Diallyl trisulfide (DATS), a natural product from garlic, has also exhibited diverse functions containing anti-inflammation, anti-oxidation, and tumor inhibition effects.8,9 Previous researches have demonstrated that diallyl sulfide (DAS), one of the OSCs in garlic, could prevent the ALF elicited by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) combined with D-galactosamine (D-gal) treatment.10 However, whether DATS could protect against ALF remains unclear. LPS can activate Kupffer cells (KCs) and macrophages to release cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-1β (IL-1β), interleukin-6 (IL-6), etc., which then lead to hepatic necrosis.11 D-gal is hepatotoxic itself and the metabolites in liver can cause hepatocyte necrosis through suppressing mRNA translation.12 Furthermore, D-gal can significantly improve the specificity of LPS by the combination with it.13 Therefore, the mice challenged by LPS plus D-gal were well-established ALF model, which can imitate the pathological features of ALF patients.14

Currently, whether DATS showed the hepatoprotective effect against the challenge by LPS plus D-gal cotreatment were explored by the detection of serum and pathology. In order to explore possible mechanisms, the activation of KCs/macrophages and Caspase-1, the expressions of key proteins in apoptosis and morphology of apoptosis were detected.

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Animal treatment

Eight weeks old male ICR mice were provided by Pengyue Laboratory Animal Co., Ltd (Jinan, China). All mice were maintained at controlled environmental conditions (temperature 20–24 °C, humidity 50–60%) with a 12-h light/12-h dark cycle and had a free access to commercial food and drinking water. After 1 week of acclimation, all mice were randomized into 6 groups: control group, DATS group, LPS/D-gal group, low, medium, and high dose DATS plus LPS/D-gal groups (n = 15). The doses of DATS were chosen according to our pretest and previous reports.15–17 The mice were orally administered with DATS (20, 40, 80 mg·kg−1; Micxy Reagent) or vehicle (corn oil) in three DATS plus LPS/D-gal groups and LPS/D-gal group 1 h before intraperitoneal injection with LPS (10 μg·kg−1, Merck KGaA) and D-gal (500 mg·kg−1, Aladdin). The mice in control group or DATS alone group received an equivalent volume of corn oil or 80-mg·kg−1 DATS combined with 0.9% saline, respectively. The doses of DATS and LPS/D-gal were based on the previous reports.10,18 After LPS/D-gal challenge for 8 h, the mice samples were collected under anesthesia. The implement of all experiments was based on the US National Institutes of Health Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care Committee of Shandong University School of Public Health (No.20171229).

2.2 Serum biochemical analyses

After 8 h of LPS and D-gal cotreatment, the blood samples from abdominal aorta were obtained and the serum was obtained by centrifuging blood at 1000 g for 15 min. The enzyme (ALT, AST, LDH) levels and Tbil content in serum were measured using Biochemical Analyzer (Beckman AU480) according to manufactures’ protocol (Medical System Biotechnology, Ningbo, China).

2.3 Histopathological examination

The liver samples were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for at least 24 h. Then, the liver was cut into 4-μm sections after dehydration in gradient ethanol and embedding in paraffin (Thermo, HM325 Rotary Microtome). After deparaffinization and rehydration, the sections of liver were stained by using hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining to observe the histology changes by Olympus AX70 microscope. Pathological sections of liver tissue were selected randomly and scored separately in each group (n = 6). The grades of the liver tissues were scored, according to the type and degree of liver injury (central vein and sinusoidal congestion, hepatocyte necrosis), as the following criterions: Grade 0: scarcely or no pathological change, Grade 1: slight congestion or presence of degenerated hepatocytes, Grade 2: moderate congestion or degeneration, Grade 3: obvious congestion or presence of necrosis hepatocytes, and Grade 4: severe hyperemia or necrosis.19

2.4 Immunohistochemistry assay of CD11b in liver

After deparaffinization, rehydration, antigen retrieval, and blocking, the liver sections were incubated with anti-CD11b monoclonal antibody (Abcam, ab133357, 1:4,000 dilution) overnight at 4 °C. The slides were then incubated with secondary antibody (SV0002-rabbit IgG) for 30 min at 37 °C. Then, the color was developed with diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (DAB) staining kit for 90 s. At last, the sections were further stained using hematoxylin and were viewed under an Olympus AX70 microscope. The Image J software was used to measure the cell numbers of CD11b positive staining in the liver.

2.5 Quantification of serum TNF-α level

The detection of serum TNF-α level was performed according to the protocols of ELISA kit (R&D Systems, DY410–05). First, 100-mL serum or standard was added into each well of TNF-α antibody-coated 96-well plate overnight. After washing away unbound substances, 100-μL detection antibody was added for 2 h. After washing, streptavidin-HRP working dilution (100 μL) was added in the dark for 20 min. Then, the substrate solution (100 μL) was added for 30 min, then adding 50-μL stop solution. The absorbance was read within 15 min by using Tecan M200 microplate reader.

2.6 TUNEL staining

To examine the apoptotic rate of the hepatocytes, TUNEL staining was performed by an in situ Cell Death Detection Kit (Roche Applied Science, #11684817910). After the slices of liver were deparaffinized and dehydrated, the sections were immersed into protease K solution. Then, the sections were incubated with 50-μL TUNEL reaction mixture (5-μL enzyme solution and 45-μL labeling solution) at 37 °C for 1 h. Subsequently, the POD transforming agent was added to the sections for 30 min at 37 °C; 100-μL DAB substrate was added to the sections for 10 min. After counterstaining with hematoxylin, the sections were viewed and the representative staining images were captured by an Olympus AX70 microscope. The proportion of TUNEL-positive cells in the liver cells was evaluated by NIH Image J software.

2.7 RNA extraction and qRT-PCR

The total RNA was isolated from the liver using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen) and its concentration was analyzed by the NanoDrop 2000c (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA); 1-μg total RNA of each sample was used to synthesize cDNA by commercial kit (Roche). The sequences of the primers for hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyl transferase (HPRT), Caspase-1, and IL-1β were the same to our previous study.18 qRT-PCR reaction was conducted with SYBR Green mix (Roche) by Roche LightCycler 480. The reaction program was as follows: pre-incubation at 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 3-step amplification of 95 °C for 10 s, 60 °C for 10 s, and 72 °C for 10 s (40 cycles).

The expression levels of selected genes were calculated after normalization to HPRT gene using the ΔΔCt method.

2.8 Tissue preparation and western blot

The liver of mice was homogenized in cold lysis buffer. After centrifugation (12,000 g, 10 min, 4 °C), the supernatants were separated and the concentration of proteins was examined by commercial BCA™ Protein assay Kits (Pierce Biotechnology, Inc.). Western blot analyses were performed as we previously reported.20 In brief, the equal protein samples were separated with 12.5% SDS-PAGE and were transferred onto PVDF membranes. After blocking in 1.5% Bovine serum albumin (BSA), the PVDF membranes were probed with the primary antibodies against cleaved Caspase-1 (Cell Signaling Technology [CST], #89332, 1:2,000), IL-1β (p17) (CST, #63124, 1:1,000), Bcl-2 (CST, #3498, 1:1,000), Bax (CST, #14796, 1:1,000), cleaved Caspase-3 (CST, #9664, 1:1,000), and β-actin (Merck KGaA, A5441, 1:3,000) overnight at 4 °C. Then, the PVDF membranes were incubated with secondary antibody for 1 h. Immunoreactive bands of proteins were visualized by exposing the membranes to an ECL detection reagent (Bedford, MA, USA) and then exposing to X-ray films. The bands on films were scanned by an Agfa DuoScan T1200 scanner. Finally, the images were analyzed by Image J software and β-actin was used as an internal standard to normalize all results.

2.9 Statistical analysis

All data were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 26.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL) and GraphPad Prism version 8 (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA). The differences between each group were determined by using one-way ANOVA, followed by LSD-t test. Two side P < 0.05 was considered to have statistical significance.

3. Results

3.1 DATS effectively protected against ALF induced by LPS/D-gal challenge

In order to evaluate the protective effects of DATS on LPS/D-gal-induced ALF, the liver injury markers in serum were firstly analyzed. As seen in Fig. 1, significant increase of ALT, AST, LDH activities, and Tbil content in serum was observed in LPS/D-gal treatment mice. However, DATS cotreatment dramatically inhibited the increase of the above values. Compared with the mice in LPS/D-gal treatment group, the serum ALT level of mice in DATS plus LPS/D-gal groups decreased by 82.3%, 89.5%, and 78.5% (P < 0.05), respectively, the activity of AST reduced by 63.8%, 78.5%, and 67.9% (P < 0.05), respectively, the LDH level reduced by 46.6%, 57.0%, and 44.0% (P < 0.05), respectively, while the Tbil level reduced by 47.1%, 48.5%, and 41.0% (P < 0.05), respectively. Only DATS treatment did not lead to significant differences in these parameters in mice.

Fig. 1.

DATS protected against LPS/D-gal-induced increasement of serum biochemical biomarkers. *P < 0.05, compared with the control group mice; #P < 0.05, compared with the LPS/D-gal group mice.

Then, the ratio of liver weight to body weight was examined. LPS/D-gal challenge significantly increased the ratio of liver weight to body weight. Interestingly, LPS/D-gal induced the increase of relative liver weight which were markedly attenuated by DATS pretreatment in LPS/D-gal-treated mice (Table 1).

Table 1.

Body weight, liver weight, and the ratio of liver weight to body weight of mice (mean ± SD).

| Group | Body weight (g) | Liver weight (g) | the ratio of liver weight to body weight |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 28.10 ± 0.48 | 1.59 ± 0.10 | 0.0541 ± 0.0049 |

| DATS | 28.30 ± 0.36 | 1.61 ± 0.11 | 0.0549 ± 0.0049 |

| LPS/D-gal | 28.30 ± 1.49 | 2.03 ± 0.41* | 0.0721 ± 0.0151* |

| Low | 28.85 ± 0.98 | 1.74 ± .12*,# | 0.0581 ± 0.0036*,# |

| Medium | 28.26 ± 0.78 | 1.67 ± 0.09*,# | 0.0592 ± 0.0033*,# |

| High | 28.29 ± 0.89 | 1.59 ± 0.10# | 0.0564 ± 0.0033# |

* P < 0.05, compared with the control group mice.

# P < 0.05, compared with the LPS/D-gal group mice.

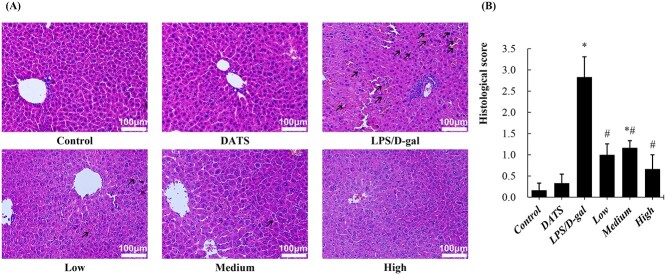

H&E staining of liver tissue revealed that LPS/D-gal treatment induced obvious pathological changes, i.e. cell degeneration or necrosis, central vein, and sinusoidal congestion. Notably, DATS pretreatment significantly alleviated the pathological changes induced by LPS/D-gal challenge. Furthermore, these pathological changes were almost completely reversed by 80-mg·kg−1 DATS treatment (Fig. 2a). Pathological grading results verified the same conclusion. The histological grade in the LPS/D-gal group increased rapidly compared with the control group and decreased in three groups pretreatment with different doses of DATS (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2.

DATS attenuated LPS/D-gal induced hepatic pathological changes. a) Representative photographs of hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining liver sections (200×) from mice of each group are shown, and the representative pathological changes are indicated with black arrows. b) The pathological scores of liver sections from mice of each group. *P < 0.05, compared with the control group mice; #P < 0.05, compared with the LPS/D-gal group mice.

3.2 DATS significantly alleviated the inflammation induced by LPS/D-gal challenge

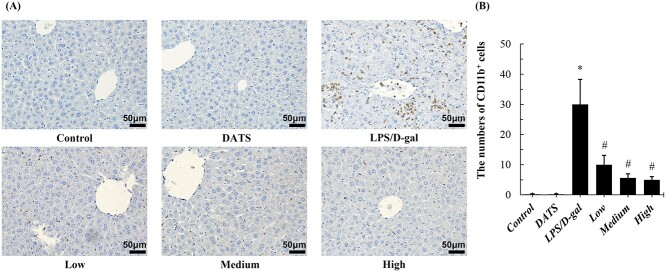

KCs and other liver-infiltrating macrophages play important roles during acute and chronic inflammation. CD11b has been shown to mediate macrophage adhesion, migration, chemotaxis, and accumulation during inflammation.21 In immunohistochemistry staining, the numbers of CD11b+ cells in liver tissue increased remarkably after LPS/D-gal challenge compared with the control group. Interestingly, DATS remarkably decreased the numbers of CD11b+ cells in LPS/D-gal treated mice. The positive staining cells numbers of CD11b were significantly lower than that of LPS/D-gal group (P < 0.05). Compared with mice in the LPS/D-gal group, the CD11b+ cells in livers of mice in DATS intervention groups decreased by 66.7%, 81.3%, and 83.3% (P < 0.05), respectively (Fig. 3). DATS alone did not lead to significant differences in this parameter in mice.

Fig. 3.

DATS pretreatment protected against ALF induced by LPS/D-gal by suppressing the activation of CD11b + cells. a) Representative photographs of CD11b staining (400×) from mice of each group. b) The numbers of CD11b+ cells were calculated by Image J software. *P < 0.05, compared with the control group mice; #P < 0.05, compared with the LPS/D-gal group mice.

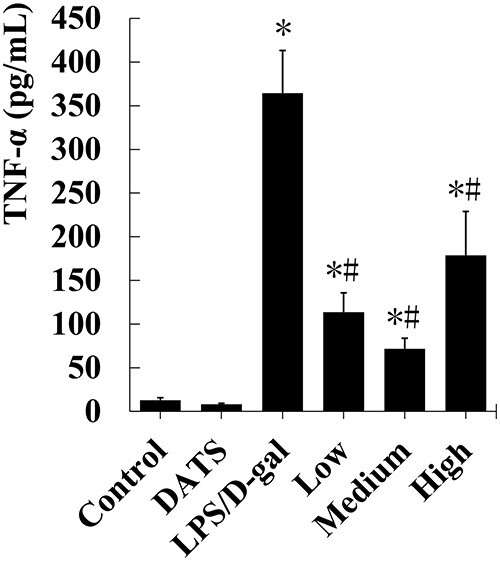

Next, we detected the levels of TNF-α, an important inflammatory factor released from KCs/macrophages. There was no significant difference between the DATS group and the control group (P > 0.05). The level of TNF-α in liver tissues was significantly increased after LPS/D-gal challenge. Compared with LPS/D-gal treated mice, the serum TNF-α level of mice in DATS plus LPS/D-gal groups decreased by 68.8%, 80.4%, and 51.0% (P < 0.05), respectively (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

DATS protected against ALF induced by LPS/D-gal by inhibiting the release of TNF-α to serum. The serum TNF-α levels were determined by ELISA kit. *P < 0.05, compared with the control group mice; #P < 0.05, compared with the LPS/D-gal group mice.

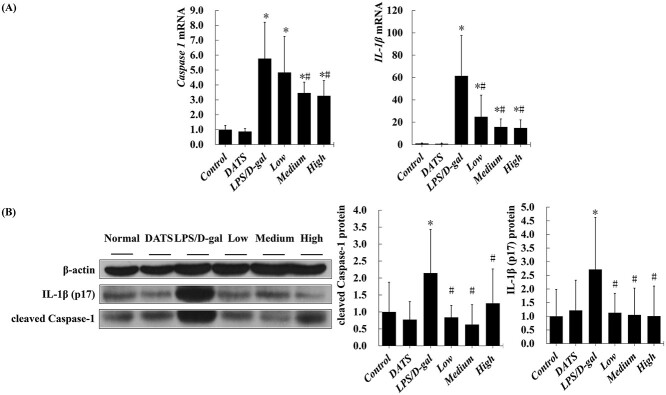

To investigate the mechanisms underlying the inflammation in LPS/D-gal induced ALF, the expressions of Caspase-1 and IL-1β were measured by western blot and qRT-PCR. The mRNA levels of hepatic Caspase-1 and IL-1β in LPS/D-gal challenge mice were significantly higher than those in the mice of control group (P < 0.05). DATS treatment inhibited high expressions of Caspase-1 and IL-1β (P < 0.05) (Fig. 5a). No significant difference of hepatic Caspase-1 and IL-1β mRNA levels was observed between DATS alone and control group. Similarly, a marked increase of the expression of IL-1β and Caspase-1, examined with western blot assay, was found in the mice of LPS/D-gal treated group when compared with the mice in control group. Interestingly, pretreatment of DATS effectively inhibited LPS/D-gal-induced the increase of Caspase-1 and IL-1β protein expression in mice liver (Fig. 5b).

Fig. 5.

DATS pretreatment suppressed the high expression of Caspase-1 and IL-1β induced by LPS/D-gal challenge. a) The mRNA levels of hepatic Caspase-1 and IL-1β; b) the protein levels of hepatic cleaved Caspase-1 and IL-1β (p17). *P < 0.05, compared with the control group mice; #P < 0.05, compared with the LPS/D-gal group mice.

3.3 DATS pretreatment effectively inhibited the apoptosis of hepatocytes induced by LPS/D-gal

Hepatocyte apoptosis has been demonstrated a critical step during the progression of ALF. As shown in Fig. 6, there was no obvious TUNEL-positive hepatocyte being found in any visual fields in the control and DATS groups. However, the numbers of TUNEL-positive hepatocytes were significantly higher after LPS/D-gal challenge, while DATS treatment markedly decreased the numbers of apoptotic hepatocytes elicited by LPS plus D-gal challenge in mice. Compared with the mice in the LPS/D-gal group, the proportion of TUNEL-positive cells in livers of mice in low, medium, and high dose of DATS plus LPS/D-gal groups decreased by 80.7%, 91.7%, and 69.3% (P < 0.05), respectively.

Fig. 6.

DATS pretreatment inhibited hepatocyte apoptosis induced by LPS/D-gal challenge. a) Representative photographs of TUNEL staining (200×) from mice of each group; b) the analysis of the fraction of TUNEL positive staining cells. *P < 0.05, compared with the control group mice; #P < 0.05, compared with the LPS/D-gal group mice.

To further investigate the underlying mechanisms of apoptosis induced by LPS/D-gal challenge, we detected the protein expression levels of cleaved Caspase-3, Bax, and Bcl-2 (all proved as apoptosis-related protein) in the liver tissue. LPS/D-gal challenge induced the increase of the protein levels of cleaved Caspase-3 and Bax compared with those in the control group (P < 0.05). Although Bcl-2, an antiapoptotic protein, had higher expression level in the mice of LPS/D-gal group, the ratio of Bcl-2/Bax was markedly lower, when compared with the parameters in the mice of control group. Coincidently, DATS pretreatment markedly suppressed the increase of cleaved Caspase-3 and Bax and the decrease of the ratio of Bcl-2/Bax in LPS/D-gal-treated mice (P < 0.05) (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

DATS pretreatment significantly inhibited the increase of cleaved Caspase-3 and Bax and the decrease of the ratio of Bcl-2/Bax induced by LPS/D-gal challenge. a) Representative western blot bands of the expression of cleaved Caspase-3, Bax, Bcl-2 in the mice liver; b) quantification of the protein levels of cleaved Caspase-3, Bax, Bcl-2, and the ratio of Bcl-2/Bax. *P < 0.05, compared with the control group mice; #P < 0.05, compared with the LPS/D-gal group mice.

4. Discussion

The present results clearly elucidated that DATS pretreatment significantly alleviated ALF induced by LPS/D-gal by anti-inflammation and anti-apoptosis. The activity of ALT in serum is the gold standard for evaluating hepatic injury, while the serum activities of AST and LDH are also used to show the degree of liver damage.22 Moreover, the elevation of serum Tbil content can show the loss of liver function.23 The biomembranes of these hepatocytes were damaged by endogenous or exogenous poisons in liver, which lead to the enzymes in the liver releasing into the blood. In our study, pretreatment of DATS down-regulated the levels of ALT, AST, and Tbil in serum, decreased liver weight/body weight ratio, and ameliorated the changes of liver histopathology in LPS/D-gal treated mice. All these results demonstrated the prominently protective ability of DATS on ALF induced by LPS/D-gal challenge in mice.

The inner mechanisms of how DATS regulates LPS/D-gal-induced ALF require further studies. KCs are a specialized population of macrophages that reside in the liver. When the liver is damaged, bone marrow-derived macrophages migrate into the liver.24 F4/80, stably expressed in mouse macrophages, can be used as a specific marker for macrophages.25 F4/80+ macrophages can be divided into two subgroups, namely CD68+F4/80+ cells with reactive oxygen species production capacity and CD11b+F4/80+ cells with cytokine-producing ability.24,26 In our study, DATS treatment did not significantly improve the oxidative stress induced by LPS/D-gal challenge (data not shown). Therefore, we examined the expression level of CD11b by immunohistochemistry staining. Immunostaining results of CD11b showed that there were amounts of scattered CD11b positive staining cells in the liver of LPS/D-gal-treated mice. It is interesting to note that DATS treatment can markedly decrease the number of CD11b positive KCs/macrophages. However, we could not differentiate the roles of DATS on liver resident KCs and recruited monocyte-derived macrophages, as CD11b is not a specific marker for liver macrophages but is expressed by various myeloid cells including liver-infiltrating neutrophils and monocytes. F4/80 is the most widely used marker of macrophages including KCs and infiltrated macrophages,27 while T-cell membrane protein 4 (Tim4) is more specific KCs markers.28,29 Therefore, the combination examination of F4/80 and Tim4 by double IHC staining or flow cytometry will help to identify whether DATS could affect the resident KCs and/or recruited macrophages.

LPS can directly stimulate macrophages to trigger liver inflammation, in which pro-inflammatory cytokines plays an important role30. TNF-α, as one of the most essential cytokines, will take part in regulation of inflammation and apoptosis.31 The activation of Caspase-1 will induce the expression of cytokines IL-1β, an important inflammation cytokine, into their active forms and initiate cascade reaction of inflammation.32,33 Our findings showed that LPS/D-gal treatment upregulated the level of serum TNF-α, the mRNA and protein expressions of IL-1β and Caspase-1. Interestingly, DATS pretreatment significantly inhibited the high expression of TNF-α, Caspase-1, and IL-1β in LPS/D-gal-treated mice. Taken together, DATS pretreatment effectively ameliorated the inflammation induced by LPS/D-gal by suppressing the activation of KCs/macrophages possibly.

TNF-α can combine with its receptors to induce apoptosis as previous reported.34 Hence, apoptosis may be alleviated by suppressing the increase of serum TNF-α. Although previous studies showed that the immune system participates in LPS/D-gal induced ALF, apoptosis also plays a key role in the development of this disease.35–37 Apoptosis is an orderly process of autonomous cell death under the control of strict and complex signal networks with induction of internal and external inducing factors.38 In our study, we found that LPS/D-gal challenge induced the hepatocytes to apoptosis by TUNEL staining. Apoptosis is mainly regulated by two pathways: exogenous pathway regulated by death receptors and endogenous pathway regulated by mitochondria.39 The balance between pro-apoptotic proteins such as Bax and anti-apoptotic proteins such as Bcl-2 in the Bcl-2 protein family is essential for regulating mitochondrial pathway-mediated apoptosis.40,41 Caspase-3 is required in the final stage of apoptosis execution, and cleaved Caspase-3 is its activated form.39,42,43 LPS/D-gal treatment significantly down-regulated the ratio of Bcl-2/Bax and upregulated the expression of cleaved Caspase-3, although the expression of pro-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 increased. Therefore, the apoptosis of hepatocytes increased in LPS/D-gal-treated mice. Pretreatment of DATS made the apoptosis-executing protein Caspase-3 expression almost return to normal levels. These results indicated that DATS can mitigate LPS/D-gal-elicited apoptosis of liver cells by downregulating the expression of Caspase-3 and upregulating the relative expression of Bcl-2 to Bax in the liver.

Altogether, our study provided strong evidence that the effects of anti-inflammation and anti-apoptosis by DATS significantly protected against ALF induced by LPS/D-gal challenge in mice. Our findings suggest that DATS might be considered as a potential drug candidate for future clinical studies.

Authors’ contributions

ZY: performed the research; YD: analyzed the data; TZ and XZ, gave critical comments; CZ: designed the study; ZY and CZ: wrote the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Key Technology Research and Development Program of Shandong (Grant no. 2017GSF18181).

Conflicts of interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Ziqiang Yu, Department of Toxicology and Nutrition, School of Public Health, Cheeloo College of Medicine, Shandong University, 44 Wenhua West Road, Jinan 250012, Shandong, China.

Yun Ding, Department of Physical and Chemical Inspection, School of Public Health, Cheeloo College of Medicine, Shandong University, 44 Wenhua West Road, Jinan 250012, Shandong, China.

Tao Zeng, Department of Toxicology and Nutrition, School of Public Health, Cheeloo College of Medicine, Shandong University, 44 Wenhua West Road, Jinan 250012, Shandong, China.

Xiulan Zhao, Department of Toxicology and Nutrition, School of Public Health, Cheeloo College of Medicine, Shandong University, 44 Wenhua West Road, Jinan 250012, Shandong, China.

Cuili Zhang, Department of Toxicology and Nutrition, School of Public Health, Cheeloo College of Medicine, Shandong University, 44 Wenhua West Road, Jinan 250012, Shandong, China.

References

- 1. Bernal W, Wendon J. Acute liver failure. N Engl J Med. 2013:369(26):2525–2534. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1208937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Squires JE, McKiernan P, Squires RH. Acute liver failure: an update. Clin Liver Dis. 2018:22(4):773–805. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2018.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Asrani SK, Devarbhavi H, Eaton J, Kamath PS. Burden of liver diseases in the world. J Hepatol. 2019:70(1):151–171. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bernal W, Lee WM, Wendon J, Larsen FS, Williams R. Acute liver failure: a curable disease by 2024? J Hepatol. 2015:62(1 Suppl):S112–S120. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rana SV, Pal R, Vaiphei K, Sharma SK, Ola RP. Garlic in health and disease. Nutr Res Rev. 2011:24(1):60–71. doi: 10.1017/s0954422410000338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zhang CL, Zeng T, Zhao XL, Yu LH, Zhu ZP, Xie KQ. Protective effects of garlic oil on hepatocarcinoma induced by N-nitrosodiethylamine in rats. Int J Biol Sci. 2012:8(3):363–374. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.3796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zeng T, Zhang CL, Zhao XL, Xie KQ. The roles of garlic on the lipid parameters: a systematic review of the literature. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2013:53(3):215–230. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2010.523148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Powolny AA, Singh SV. Multitargeted prevention and therapy of cancer by diallyl trisulfide and related Allium vegetable-derived organosulfur compounds. Cancer Lett. 2008:269(2):305–314. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.05.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yun HM, Ban JO, Park KR, Lee CK, Jeong HS, Han SB, Hong JT. Potential therapeutic effects of functionally active compounds isolated from garlic. Pharmacol Therapeut. 2014:142(2):183–195. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2013.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Li M, Wang S, Li XJ, Jiang LL, Wang XJ, Kou RR, Wang Q, Xu L, Zhao N, Xie KQ. Diallyl sulfide protects against lipopolysaccharide/D-galactosamine-induced acute liver injury by inhibiting oxidative stress, inflammation and apoptosis in mice. Food Chem Toxicol. 2018:120:500–509. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2018.07.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tanaka KA, Kurihara S, Shibakusa T, Chiba Y, Mikami T. Cystine improves survival rates in a LPS-induced sepsis mouse model. Clin Nutr. 2015:34(6):1159–1165. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2014.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Czekaj P, Król M, Limanówka Ł, Michalik M, Lorek K, Gramignoli R. Assessment of animal experimental models of toxic liver injury in the context of their potential application as preclinical models for cell therapy. Eur J Pharmacol. 2019:861:172597. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2019.172597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wang JB, Wang HT, Li LP, Yan YC, Wang W, Liu JY, Zhao YT, Gao WS, Zhang MX. Development of a rat model of D-galactosamine/lipopolysaccharide induced hepatorenal syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2015:21(34):9927–9935. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i34.9927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ansari MA, Raish M, Bin Jardan YA, Ahmad A, Shahid M, Ahmad SF, Haq N, Khan MS, Bakheet SA. Sinapic acid ameliorates D-galactosamine/lipopolysaccharide-induced fulminant hepatitis in rats: role of nuclear factor erythroid-related factor 2/heme oxygenase-1 pathways. World J Gastroenterol. 2021:27(7):592–608. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v27.i7.592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chen LY, Chen Q, Cheng YF, Jin HH, Kong DS, Zhang F, Wu L, Shao JJ, Zheng SZ. Diallyl trisulfide attenuates ethanol-induced hepatic steatosis by inhibiting oxidative stress and apoptosis. Biomed Pharmacother. 2016:79:35–43. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2016.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yang YL, Jiang LL, Wang S, Zeng T, Xie KQ. Diallyl trisulfide protects the liver against hepatotoxicity induced by isoniazid and rifampin in mice by reducing oxidative stress and activating Kupffer cells. Toxicol Res (Camb). 2016:5(3):954–962. doi: 10.1039/c5tx00440c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zeng T, Zhang CL, Zhu ZP, Yu LH, Zhao XL, Xie KQ. Diallyl trisulfide (DATS) effectively attenuated oxidative stress-mediated liver injury and hepatic mitochondrial dysfunction in acute ethanol-exposed mice. Toxicology. 2008:252(1-3):86–91. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2008.07.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ding Y, Yu ZQ, Zhang CL. Diallyl trisulfide protects against concanavalin A-induced acute liver injury in mice by inhibiting inflammation, oxidative stress and apoptosis. Life Sci. 2021:278:119631. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2021.119631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mao JX, Yi M, Wang R, Huang YS, Chen M. Protective effects of costunolide against D-galactosamine and lipopolysaccharide-induced acute liver injury in mice. Front Pharmacol. 2018:9:1469. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.01469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zhang CL, Zeng T, Zhao XL, Xie KQ. Garlic oil suppressed nitrosodiethylamine-induced hepatocarcinoma in rats by inhibiting PI3K-AKT-NF-κB pathway. Int J Biol Sci. 2015:11(6):643–651. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.10785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Schmid MC, Khan SQ, Kaneda MM, Pathria P, Shepard R, Louis TL, Anand S, Woo G, Leem C, Faridi MH, et al. Integrin CD11b activation drives anti-tumor innate immunity. Nat Commun. 2018:9(1):5396. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07387-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Amacher DE. A toxicologist's guide to biomarkers of hepatic response. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2002:21(5):253–262. doi: 10.1191/0960327102ht247oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ozer J, Ratner M, Shaw M, Bailey W, Schomaker S. The current state of serum biomarkers of hepatotoxicity. Toxicology. 2008:245(3):194–205. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2007.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kinoshita M, Uchida T, Sato A, Nakashima M, Nakashima H, Shono S, Habu Y, Miyazaki H, Hiroi S, Seki S. Characterization of two F4/80-positive Kupffer cell subsets by their function and phenotype in mice. J Hepatol. 2010:53(5):903–910. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gordon S, Hamann J, Lin HH, Stacey M. F4/80 and the related adhesion-GPCRs. Eur J Immunol. 2011:41(9):2472–2476. doi: 10.1002/eji.201141715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sato A, Nakashima H, Nakashima M, Ikarashi M, Nishiyama K, Kinoshita M, Seki S. Involvement of the TNF and FasL produced by CD11b Kupffer cells/macrophages in CCl4-induced acute hepatic injury. PLoS One. 2014:9(3):e92515. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zhang XN, Zhao N, Guo FF, Wang YR, Liu SX, Zeng T. Diallyl disulfide suppresses the lipopolysaccharide-driven inflammatory response of macrophages by activating the Nrf2 pathway. Food Chem Toxicol. 2022:159:112760. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2021.112760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chow A, Schad S, Green MD, Hellmann MD, Allaj V, Ceglia N, Zago G, Shah NS, Sharma SK, Mattar M, et al. Tim-4+ cavity-resident macrophages impair anti-tumor CD8+ T cell immunity. Cancer Cell. 2021:39(7):973–988.e979. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2021.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zhang CY, Liu S, Yang M. Functions of two distinct Kupffer cells in the liver. Exp Ther Med. 2021:2(6):511–515. doi: 10.37349/emed.2021.00067. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Triantafyllou E, Woollard KJ, McPhail MJW, Antoniades CG, Possamai LA. The role of monocytes and macrophages in acute and acute-on-chronic liver failure. Front Immunol. 2018:9:2948. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zelová H, Hošek J. TNF-α signalling and inflammation: interactions between old acquaintances. Inflamm Res. 2013:62(7):641–651. doi: 10.1007/s00011-013-0633-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sun Q, Scott MJ. Caspase-1 as a multifunctional inflammatory mediator: noncytokine maturation roles. J Leukoc Biol. 2016:100(5):961–967. doi: 10.1189/jlb.3MR0516-224R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Szabo G, Petrasek J. Inflammasome activation and function in liver disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015:12(7):387–400. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2015.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Van Herreweghe F, Festjens N, Declercq W, Vandenabeele P. Tumor necrosis factor-mediated cell death: to break or to burst, that’s the question. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2010:67(10):1567–1579. doi: 10.1007/s00018-010-0283-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Deng YL, Chen C, Yu HG, Diao H, Shi CC, Wang YG, Li GM, Shi M. Oridonin ameliorates lipopolysaccharide/D-galactosamine-induced acute liver injury in mice via inhibition of apoptosis. Am J Transl Res. 2017:9(9):4271–4279. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Li L, Yin HY, Zhao Y, Zhang XF, Duan CL, Liu J, Huang CX, Liu SH, Yang SY, Li XJ. Protective role of puerarin on LPS/D-gal induced acute liver injury via restoring autophagy. Am J Transl Res. 2018:10(3):957–965. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Yang YQ, Shao RY, Jiang R, Zhu M, Tang L, Li LJ, Li Z. β-Hydroxybutyrate exacerbates lipopolysaccharide/d-galactosamine-induced inflammatory response and hepatocyte apoptosis in mice. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 2019:33(9):e22372. doi: 10.1002/jbt.22372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wang KW. Molecular mechanisms of hepatic apoptosis regulated by nuclear factors. Cell Signal. 2015:27(4):729–738. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2014.11.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wong RS. Apoptosis in cancer: from pathogenesis to treatment. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2011:30(1):87. doi: 10.1186/1756-9966-30-87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Degterev A, Yuan J. Expansion and evolution of cell death programmes. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008:9(5):378–390. doi: 10.1038/nrm2393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Dietrich JB. Apoptosis and anti-apoptosis genes in the Bcl-2 family. Arch Physiol Biochem. 1997:105(2):125–135. doi: 10.1076/apab.105.2.125.12927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Elmore S. Apoptosis: a review of programmed cell death. Toxicol Pathol. 2007:35(4):495–516. doi: 10.1080/01926230701320337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Jia YN, Lu HP, Peng YL, Zhang BS, Gong XB, Su J, Zhou Y, Pan MH, Xu L. Oxyresveratrol prevents lipopolysaccharide/d-galactosamine-induced acute liver injury in mice. Int Immunopharmacol. 2018:56:105–112. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2018.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]