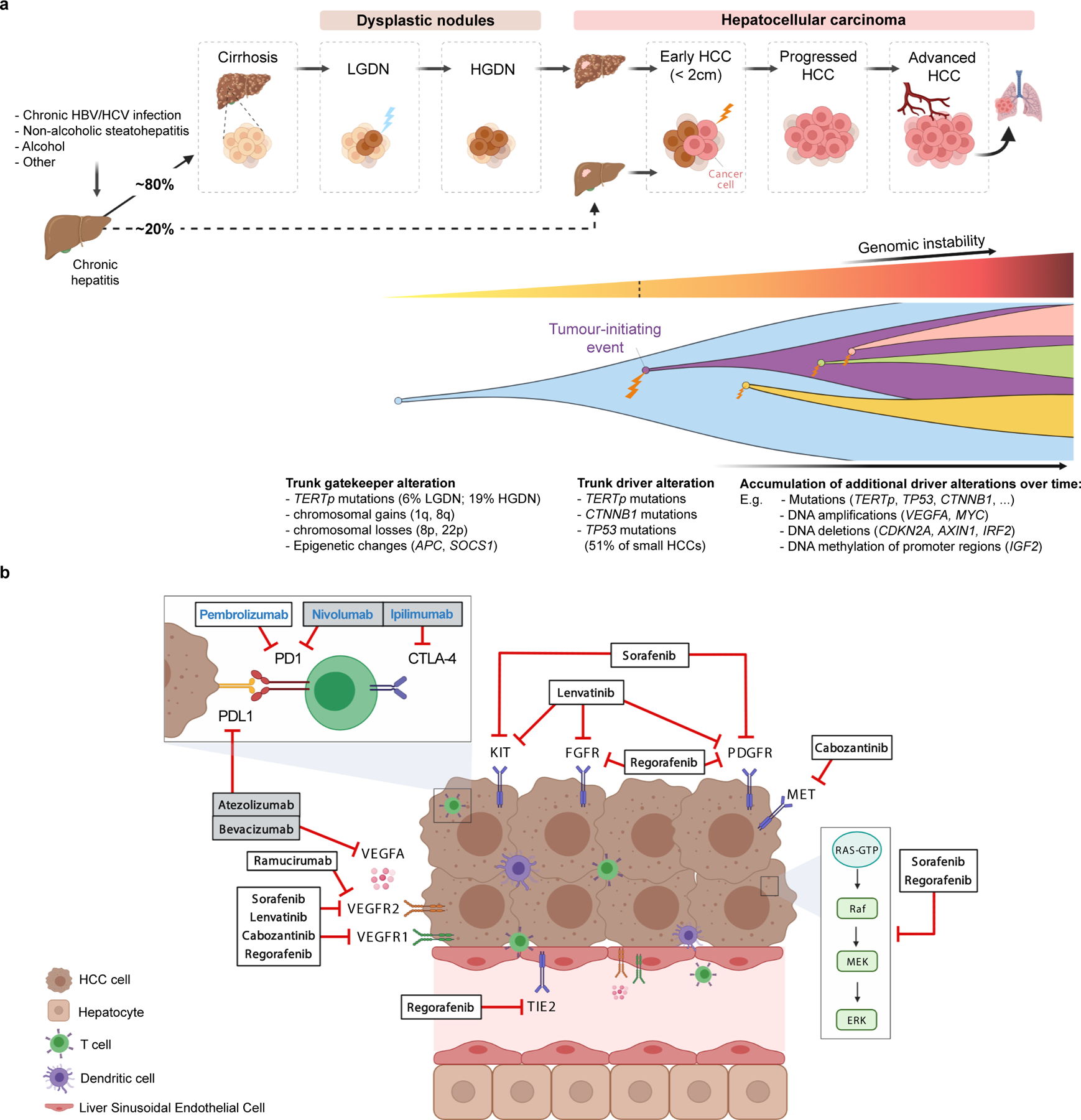

Figure 1.

A) Molecular pathogenesis of HCC: step-by-step process, genomic hits and clonal evolution. Both genetic and epigenetic mechanisms (TERT promoter mutations, chromosomal aberrations and methylation events) are thought to function as gatekeepers for malignant transformation of dysplastic nodules. Hepatocarcinogenesis requires a tumour-initiation event such as mutations in TERT, TP53 and CTNNB1, which are already present in 51% of small HCC tumors. Further acquired genetic alterations and changes to the tumour microenvironment enable these tumors to progress to advanced stages under the constant pressure of evolutional selection, leading to vast intratumoral heterogeneity. HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HGDN, high-grade dysplastic nodules; LGDN, low-grade dysplastic nodules; TERTp, TERT promoter.

B) Molecular depiction of systemic therapies in HCC. Tumor cells, liver sinusoidal endothelial cells and lymphocytes are represented in relation to tyrosine kinase inhibitors, immunotherapies and monoclonal antibodies approved in HCC based on phase III data. Therapy names in bold black indicate positive results based on phase III trials, either with a superiority design (atezolizumab plus bevacizumab, sorafenib, regorafenib, cabozantinib and ramucirumab) or with a non-inferiority design (lenvatinib). Therapy names in bold blue designate other FDA-approved drugs based on non-randomized phase II trials (pembrolizumab and nivolumab plus ipilimumab). Grey boxes indicate combination therapies.