To the Editor,

Point-of-Care Ultrasonography (POCUS) is a non-invasive bedside diagnostic tool, which can be used as an adjunct to physical examination in the quest to objectively assess a patient’s intravascular fluid status [1]. There has been a rapid uptake of POCUS in multiple specialties in the recent past, including nephrology and critical care medicine [2, 3]. Assessment of inferior vena cava (IVC) diameter and inspiratory collapse allows estimation of right atrial pressure (RAP) and is widely used by novice users due to relative ease of image acquisition. However, there are many pitfalls to solely using IVC measurements for making clinical decisions. For instance, collapsibility of the vessel is often affected by patient’s respiratory effort, site of measurement, and sonographic plane of evaluation. Moreover, in patients with chronically elevated RAP such as those with pulmonary hypertension and tricuspid regurgitation, IVC can be dilated at baseline with reduced collapsibility. Through this case, we intend to demonstrate the utility of portal vein Doppler as an add-on parameter to IVC ultrasound in patients with tricuspid regurgitation.

A 42-year-old man with a history of ESKD on maintenance hemodialysis, chronic pulmonary hypertension, and severe tricuspid regurgitation presented to the emergency department with shortness of breath and worsening pedal edema after missing dialysis. He was found to have hyperkalemia (serum potassium 6.9 mmol/L), metabolic acidosis (serum bicarbonate 15 mmol/L), and hyperphosphatemia (serum phosphorus 9 mg/dL). The patient underwent urgent hemodialysis to address metabolic abnormalities and hypervolemia. Next day, we sought to determine whether he would benefit from an additional session of ultrafiltration prior to discharge. While the patient was asymptomatic with significant improvement in pedal edema, POCUS demonstrated a plethoric IVC with a maximal diameter of ~ 2.9 cm. Although an enlarged IVC generally suggests intravascular volume overload, this was less reliable in our patient as he had tricuspid regurgitation and IVC could be chronically enlarged. To investigate this further, Doppler ultrasonography of the portal vein was performed, which revealed significantly increased pulsatility suggestive of venous congestion and hypervolemia. Interestingly, blood pressure at the time of evaluation was 136/84 mmHg. This is notable, because we tend to assume that hypervolemia in dialysis patients is always associated with high blood pressure. Based on the POCUS findings, patient underwent another session of hemodialysis with an ultrafiltration of 4200 ml. Repeat POCUS performed immediately after dialysis revealed persistently enlarged IVC but normalization of the portal vein Doppler waveform (Figs. 1 and 2).

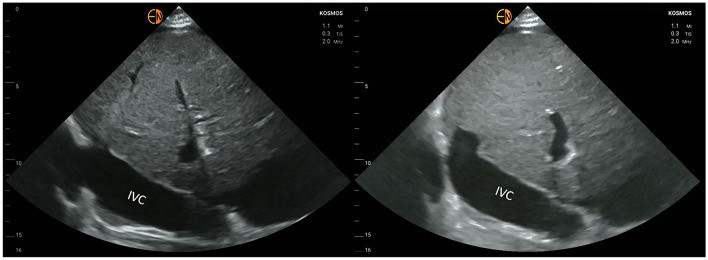

Fig. 1.

Longitudinal view of the inferior vena cava (IVC) before (A) and after (B) ultrafiltration. There is no significant change in the diameter

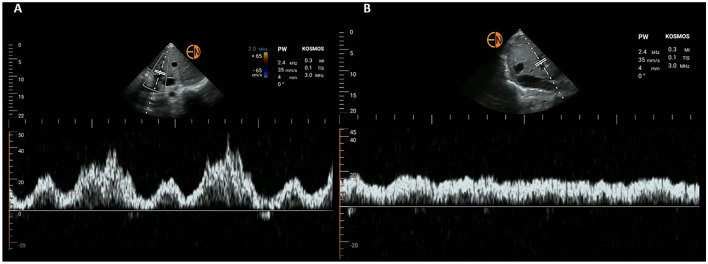

Fig. 2.

Portal vein Doppler before (A) and after (B) ultrafiltration. Note the transition from pulsatile to near-continuous pattern. Variations in amplitude (in panel A) are likely due to atrial flutter

Our case portrays the importance of portal vein Doppler, especially in physiologically challenging patients. The normal portal waveform is relatively continuous, with gentle undulation, primarily influenced by atrial contraction. Increases in RAP are transmitted to the portal circulation leading to a ‘pulsatile’ flow pattern (more than 30% is considered abnormal) as seen in our case. Unlike hepatic vein, which is a direct tributary of IVC, portal vein is separated by hepatic sinusoids that prevent linear transmission of RAP [4]. Therefore, even when IVC is chronically dilated and hepatic vein Doppler is abnormal in patients with tricuspid regurgitation, portal vein Doppler can still be used to gauge volume status. Figure 3 illustrates the changes in portal waveform with increasing RAP. In addition to quantifying venous congestion, dynamic nature of this parameter allows us to monitor the response to decongestive therapy in real time. For example, in a recent case series, Argaiz et al. have demonstrated that improvement in portal vein pulsatility coincides with resolution of acute kidney injury in patients with acute decompensated heart failure [5]. In another interesting study involving a cohort of cardiac surgery patients, portal vein pulsatility was associated with an increased risk of acute kidney injury (odds ratio 4.31) [6]. Notably, the relationship between portal vein Doppler pattern and systemic venous congestion has been long recognized [7, 8], though it gained widespread attention only in the recent past. Future studies are needed in ESKD patients to evaluate the impact of venous Doppler-guided ultrafiltration on practical outcomes such as heart failure-related hospitalizations and blood pressure control.

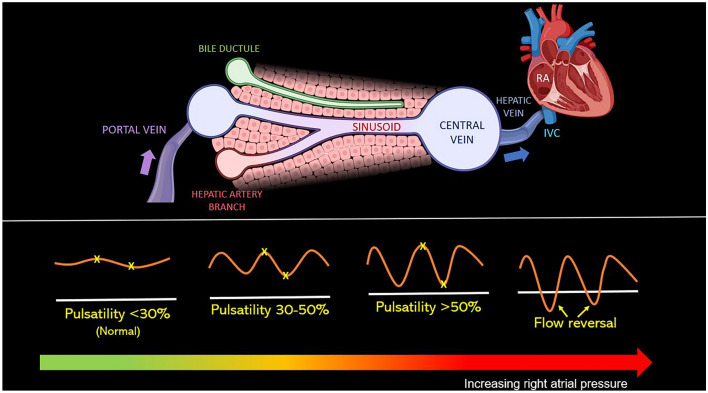

Fig. 3.

(Top panel) Illustration demonstrating how the portal vein is anatomically separated from the central venous system by hepatic sinusoids. Made using Biorender®. (Lower panel) illustration demonstrating how the portal vein Doppler waveform changes with increasing right atrial pressure. Pulsatility is the percent change in velocity of the highest and lowest points in the same cardiac cycle. IVC inferior vena cava, RA right atrium

Author contributions

Both the authors have made substantial contribution to the preparation of this manuscript.

Funding

No specific financial support was obtained for preparation of this article.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

Human and animal rights (with IRB approval number)

This article does not contain clinical trial/research with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

Consent obtained from the patient for publication of de-identified images and case.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Koratala A, Kazory A. Point of care ultrasonography for objective assessment of heart failure: integration of cardiac, vascular, and extravascular determinants of volume status. Cardiorenal Med. 2021;11:5–17. doi: 10.1159/000510732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koratala A, Olaoye OA, Bhasin-Chhabra B, Kazory A. A blueprint for an integrated point-of-care ultrasound curriculum for nephrology trainees. Kidney360. 2021 doi: 10.34067/KID.0005082021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guevarra K, Greenstein Y. Ultrasonography in the critical care unit. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2020;22(11):145. doi: 10.1007/s11886-020-01393-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lautt WW, Greenway CV. Conceptual review of the hepatic vascular bed. Hepatology. 1987;7(5):952–963. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840070527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Argaiz ER, Rola P, Gamba G. dynamic changes in portal vein flow during decongestion in patients with heart failure and cardio-renal syndrome: a POCUS case series. Cardiorenal Med. 2021;11(1):59–66. doi: 10.1159/000511714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beaubien-Souligny W, Eljaiek R, Fortier A, Lamarche Y, et al. The association between pulsatile portal flow and acute kidney injury after cardiac surgery: a retrospective cohort study. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2018;32(4):1780–1787. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2017.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duerinckx AJ, Grant EG, Perrella RR, Szeto A, et al. The pulsatile portal vein in cases of congestive heart failure: correlation of duplex Doppler findings with right atrial pressures. Radiology. 1990;176(3):655–658. doi: 10.1148/radiology.176.3.2202011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Catalano D, Caruso G, DiFazzio S, Carpinteri G, et al. Portal vein pulsatility ratio and heart failure. J Clin Ultrasound. 1998;26(1):27–31. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0096(199801)26:1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]