Serious chronic illness and mental health comorbidity

Patients with serious chronic illness, such as cancer, experience high rates of mental health comorbidity that is under-diagnosed, under-treated, and under-studied (Cheung et al., 2019). The standard of serious illness care includes specialty care e.g., oncologic care) and longitudinally integrated palliative care; the benefits of palliative care for patients with serious illnesses are well described and include improved quality of life, decreased symptom burden, increased goal-concordant care, and caregiver support (Ferrell et al., 2017).

The high rates of mental health comorbidity in patients with serious chronic illness are reflected in the inclusion of mental health metrics in palliative care quality frameworks, such as the National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care (NCP) (Ferrell et al., 2018). Mental health comorbidity within this population negatively impacts outcomes, including access to specialty care, symptom management, place of death, mental health service utilization, and advance care planning (Antunes et al., 2020; Marte et al., 2021). Data from oncology suggest that patients with mental illness benefit from highly coordinated integration of mental health and oncologic services, with a recent study showing that these integrative models positively impacted cancer care for 83.3% of patients (Irwin et al., 2019). In spite of this, the integration of mental healthcare into palliative care remains in its infancy (Cheung et al., 2019).

Multiple factors contribute to the lack of mental health integration into palliative care. Despite the burden of mental health comorbidity in palliative care, palliative care clinicians often lack the time, training, or systematic support to provide mental health services (Patterson et al., 2014). Few palliative care teams have dedicated mental health clinicians; palliative care social workers are frequently assigned as designated mental health clinicians on palliative care teams but often have compound roles with competing tasks (Middleton et al., 2020). The lack of integrated mental health clinicians on palliative care teams is particularly noteworthy given the diagnostic challenges of detecting and managing psychopathology in the setting of serious medical illness (Ng et al., 2015). As a result, screening and treatment of mental health conditions among those with serious illness remains suboptimal.

The collaborative care model: a framework for mental health integration

The collaborative care model (CCM), which was first developed to address the lack of mental health services for depression and other common mental health conditions in primary care, constitutes an effective approach for integrating mental health into medical care (Thota et al., 2012). The CCM is a framework for care integration oriented around five guidelines: patient-centered care, population-based care, measurement-based care, evidence-based care, and accountable care with continuous quality improvement. It centers around a multidisciplinary care team, such as primary care physicians, consulting mental health clinicians, and case managers who facilitate coordination of care. The model has demonstrated improved health outcomes and patient satisfaction (Woltmann et al., 2012).

The CCM has been applied across a range of clinical environments to ameliorate clinical siloing; however, it has not been utilized to integrate mental health in the palliative care setting (Cheung et al., 2019). While the CCM has not been utilized for palliative care–mental health integration, collaborative care can be adapted to palliative care. Existing frameworks utilizing collaborative care principles to integrate oncology and palliative care have demonstrated success in improving rates of advance care planning (48% vs. 63%, P = 0.021) and appropriate utilization of hospice services (19% vs. 31%, P = 0.034) (Hanson et al., 2021). However, such models have not addressed mental health integration. The development of adapted collaborative care models between oncology and palliative care in the absence of mental health integration risks codifying models of serious illness care that fail to address the mental health needs of patients (Bankston and Glazer, 2013). However, such models also suggest a possible path forward to integrating mental health and palliative care.

Implementing a collaborative palliative care model into clinical practice

Patients with serious chronic illness and their providers would benefit from collaborative care aimed at integrating mental health and palliative care. This type of integration could be accomplished by expanding upon existing CCM components. We provide preliminary recommendations for palliative care–mental health integration using collaborative care principles and existing literature of integrated care implementation (Vanderlip et al., 2016).

-

1

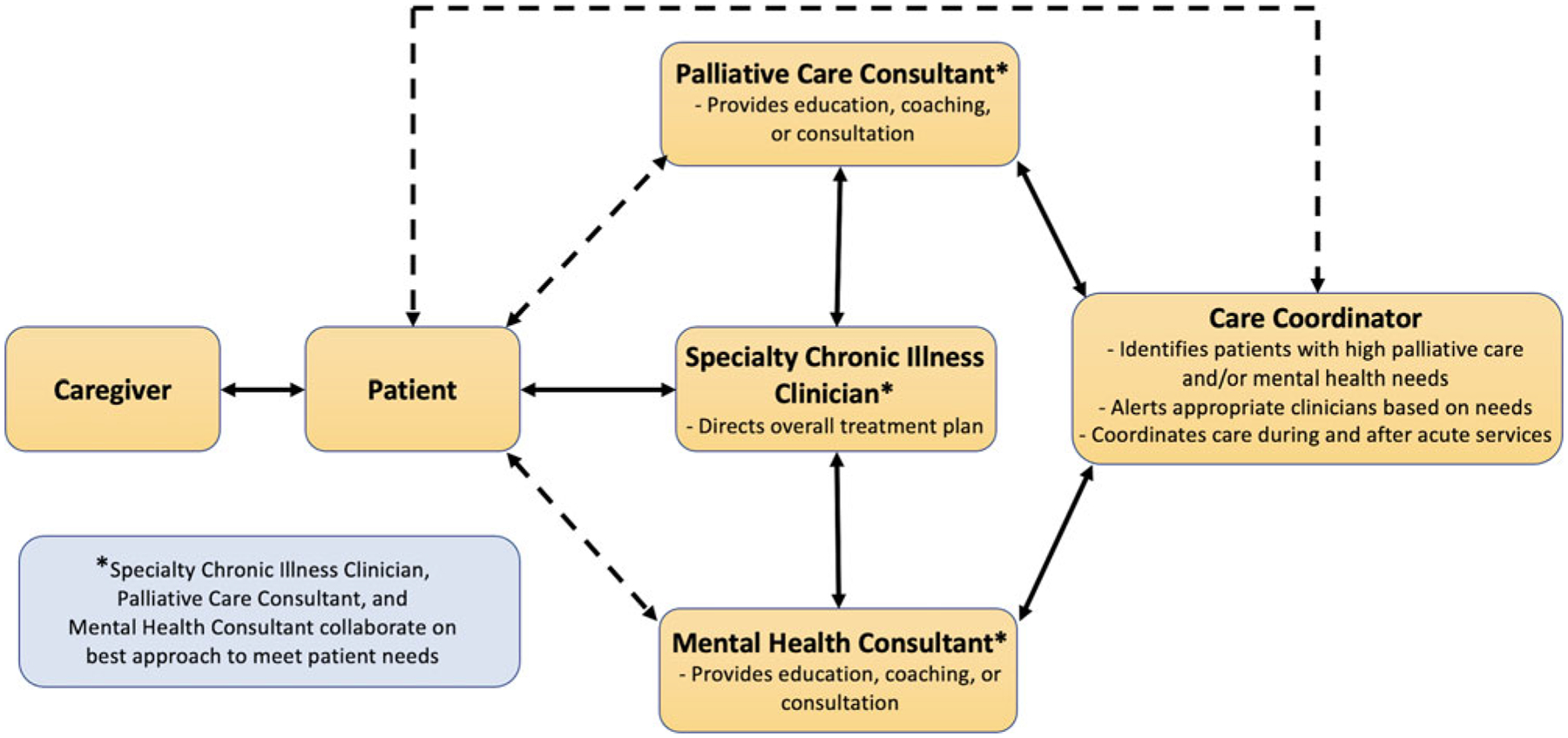

Team structure: It includes the patient, their caregiver, a specialty chronic illness clinician (e.g., an oncologist), a palliative care consultant, a mental health consultant (e.g., a psychiatrist), and a care coordinator who facilitates collaboration between specialties (Figure 1).

Fig. 1.

Collaborative team structure and processes of specialty chronic illness care, palliative care, and mental healthcare integration, adapted from Hanson et al. (2021).

The CCM emphasizes interdisciplinary teaching and indirect consultative processes. By integrating a mental health consultant directly into the collaborative palliative care framework, other team members can receive education, coaching, and care management assistance for patients with mental health issues. With a more comprehensive care team, the care coordinator can then connect each patient to the appropriate specialty care clinicians based on their serious illness or mental health needs. Through this multidisciplinary approach, patients and care team members can practice improved shared decision-making, create cohesive longitudinal care plans, develop contingency plans for crisis management, implement treatments that come from specialist recommendations, and more successfully navigate difficult advance care planning conversations.

-

2

Workforce development: To ensure population-focused care, develop training for palliative and specialty chronic illness care clinicians targeted at mental health communication techniques, strategies to navigate complex advance care planning conversations, standardized evaluations, management of common psychiatric comorbidities, and augmentation of care based on positive mental health screening.

CCM-based models have emphasized the need for palliative care communication skills education for medical oncologists and other specialty serious illness clinicians through intensive training sessions led by palliative care specialists. As the palliative care patient population has demonstrated higher rates of mental health comorbidity, this approach can be expanded to improve the mental health skill set of both palliative and specialty serious illness clinicians by including mental health training initiatives. Such mental health–serious illness workforce development has been described on the conceptual level to promote the development of skills and competencies that align with the core clinical functions required to deliver integrated care (Shalev et al., 2020).

-

3

Operationalized screening and population health: To identify evidence- and measurement-based patient mental healthcare needs, utilize standardized, systematic mental health screening measures to stratify and track patients receiving palliative care.

Many palliative and specialty serious illness care specialists have encouraged the use of systematic approaches in assessing patient and caregiver needs through the use of standardized clinical tools, such as the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale (Hui and Bruera, 2017). Although helpful in addressing somatic aspects of a patient’s life-limiting illness or acute condition, these measures may not effectively screen for mental health needs (Bagha et al., 2013). As early identification and management of depression, anxiety, and other mental health comorbidities can lead to improved outcomes (Wang et al., 2005), CCM-based palliative care models should include mental health screening measures, such as the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) and the General Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7), upon evaluation and throughout the treatment course. Such screening empowers care coordinators to appropriately link patients to services and clinicians to provide further assessment and management.

-

4

Evidence-based mental health treatment: To ensure evidence- and measurement-based mental healthcare delivery, utilize preventative and solution-focused mental health interventions that are adapted to the needs of patients with serious chronic illness.

After identifying the mental health needs of each patient, providers can then deliver stepped, measurement-based mental healthcare, including psychopharmacological and psychosocial interventions. Through the previously mentioned workforce development and training, palliative and specialty chronic illness care providers can provide first-line psychopharmacologic interventions for mental health issues, including depression, anxiety, and agitation. Second-line and more complex psychopharmacologic interventions can be further utilized through collaboration with the mental health consultant, ensuring that specialist recommendations and evidence-based treatments are guiding patient care plans.

-

5

Accountability and quality improvement: To ensure accountability and quality improvement in a collaborative palliative care model, assess the effectiveness of the adapted model by measuring outcomes that include components of mental health integration.

While such measures have not yet been formally introduced in palliative care, systems of measurement for the integration of mental healthcare have been disseminated (Miller et al., 2011). Furthermore, existing models of assessing mental health integration align well with palliative care quality metrics like the NCP. Quality metrics in mental health integration can be tailored to palliative care settings under interdisciplinary expert guidance; they should include access to mental health treatment for palliative care patients, continuity of mental health treatment for patients with progressive disease, and involvement of mental health clinicians in advance care planning and other psychosocially complex aspects of palliative care.

Conclusion

Models of palliative care–specialist serious illness care integration have allowed a greater number of people to enjoy the benefits of palliative care. Mental health integration is the next frontier in providing holistic care to individuals living with serious illnesses. Models of mental health–medical integration, such as the CCM, are attractive means by which to achieve mental health integration because they have been used effectively to improve mental health service delivery in primary care and other medical settings; they have also been adapted to palliative care integration with oncology and other medical fields. The tripartite integration of specialty medical care, palliative care, and mental health is low-hanging fruit for the alleviation of suffering and improvement of quality of life. Thus, the authors call on research funders and healthcare institutions to support these efforts, as the building blocks are there; all we must do is start stacking.

Acknowledgment.

R.J.W., D.S., and M.C.R. conceived of the presented idea, developed the theory, and wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed and contributed equally to the final manuscript. As the corresponding author, R.J.W. had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Funding.

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest. There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Antunes B, Rodrigues PP, Higginson IJ, et al. (2020) Determining the prevalence of palliative needs and exploring screening accuracy of depression and anxiety items of the integrated palliative care outcome scale: A multi-centre study. BMC Palliative Care 19(1), 69. doi: 10.1186/s12904-020-00571-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagha SM, Macedo A, Jacks LM, et al. (2013) The utility of the edmonton symptom assessment system in screening for anxiety and depression. European Journal of Cancer Care 22(1), 60–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2012.01369.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bankston K and Glazer G (2013) Legislative: Interprofessional collaboration: What’s taking so long? The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing 19(1). doi: 10.3912/OJIN.Vol18No01LegCol01 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung S, Spaeth-Rublee B, Shalev D, et al. (2019) A model to improve behavioral health integration into serious illness care. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 58(3), 503–514.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2019.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrell BR, Temel JS, Temin S, et al. (2017) Integration of palliative care into standard oncology care: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. Journal of Clinical Oncology 35(1), 96–112. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.70.1474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrell BR, Twaddle ML, Melnick A, et al. (2018) National consensus project clinical practice guidelines for quality palliative care guidelines, 4th edition. Journal of Palliative Medicine 21(12), 1684–1689. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2018.0431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson LC, Wessell KL, Hanspal J, et al. (2021) Pre-post evaluation of collaborative oncology palliative care for patients with stage IV cancer. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2021.02.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hui D and Bruera E (2017) The edmonton symptom assessment system 25 years later: Past, present, and future developments. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 53(3), 630–643. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2016.10.370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irwin KE, Park ER, Fields LE, et al. (2019) Bridge: Person-centered collaborative care for patients with serious mental illness and cancer. The Oncologist 24(7), 901–910. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2018-0488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marte C, George L, Rutherford S, et al. (2021) Unmet mental health needs in patients with advanced B-cell lymphomas. Palliative & Supportive Care 1–6. doi: 10.1017/S1478951521001164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middleton AA, Head BA and Remke SS (2020) Role of the hospice and palliative care social worker #390. Journal of Palliative Medicine 23(4), 573–574. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2019.0698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller BF, Kessler R and Peek CJ (2011). A National Agenda for Research in Collaborative Care: Papers from the Collaborative Care Research Network Research Development Conference: A Framework for Collaborative Care Metrics. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. AHRQ Publication No. 11–0067. Available at: https://archive.ahrq.gov/research/findings/final-reports/collaborativecare/collabcare.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Ng F, Crawford GB and Chur-Hansen A (2015) Depression means different things: A qualitative study of psychiatrists’ conceptualization of depression in the palliative care setting. Palliative & Supportive Care 13(5), 1223–1230. doi: 10.1017/S1478951514001187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson KR, Croom AR, Teverovsky EG, et al. (2014) Current state of psychiatric involvement on palliative care consult services: Results of a national survey. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 47(6), 1019–1027. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.06.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shalev D, Docherty M, Spaeth-Rublee B, et al. (2020) Bridging the behavioral health gap in serious illness care: Challenges and strategies for workforce development. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 28(4), 448–462. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2019.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thota AB, Sipe TA, Byard GJ, et al. (2012) Collaborative care to improve the management of depressive disorders: A community guide systematic review and meta-analysis. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 42(5), 525–538. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.01.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderlip ER, Rundell J, Avery M, et al. (2016). Dissemination of Integrated Care within Adult Primary Care Settings: The Collaborative Care Model. SAMHSA-HRSA. Available at: https://ncibh.org/resources/dissemination-of-integrated-care-within-adult-primary-care-settings-the-collaborative-care-model. [Google Scholar]

- Wang PS, Berglund P, Olfson M, et al. (2005) Failure and delay in initial treatment contact after first onset of mental disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Archives of General Psychiatry 62(6), 603613. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woltmann E, Grogan-Kaylor A, Perron B, et al. (2012) Comparative effectiveness of collaborative chronic care models for mental health conditions across primary, specialty, and behavioral health care settings: Systematic review and meta-analysis. The American Journal of Psychiatry 169(8), 790–804. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.11111616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]