Abstract

This study theoretically determines the effect of substituents on the stability of the triple-bonded L–E13 N–L (E13 = B, Al, Ga, In, and Tl) compound using the M06-2X/Def2-TZVP, B3PW91/Def2-TZVP, and B3LYP/LANL2DZ+dp levels of theory. Five small substituents (F, OH, H, CH3 and SiH3) and four large substituents (SiMe(SitBu3)2, SiiPrDis2, Tbt ( C6H2-2,4,6-{CH(SiMe3)2}3) and Ar* ( C6H3-2,6-(C6H2-2,4,6-i-Pr3)2)) are used. Unlike other triply bonded L–E13 P–L, L–E13 As–L, L–E13 Sb–L and L–E13 Bi–L molecules that have been studied, the theoretical findings for this study show that both small (but electropositive) ligands and bulky substituents can effectively stabilize the central E13 N triple bond. Nevertheless, these theoretical observations using the natural bond orbital and the natural resonance theory show that the central E13 N triple bond in these acetylene analogues must be weak, since these E13 N compounds with various ligands do not have a real triple bond.

This study theoretically determines the effect of substituents on the stability of the triple-bonded L–E13

N–L (E13 = B, Al, Ga, In, and Tl) compound using the M06-2X/Def2-TZVP, B3PW91/Def2-TZVP, and B3LYP/LANL2DZ+dp levels of theory.

1. Introduction

Molecules that feature multiple bonds have been the subject of many studies because of their economic and academic importance.1–49 Recently, molecules containing a L–E13 E15–L (E13 = B, Al, Ga, In, and Tl; E15 = P, As, Sb, and Bi) triple bond, which are isoelectronic to the alkyne analogues R–E14 E14–R (E14 = C, Si, Ge, Sn and Pb), have been the subject of theoretical study.52–65 This study focuses on the other acetylene analogues; i.e., the triply bonded L–E13 N–L compounds that contain group 13 (E13) and nitrogen atoms. As far as the authors are aware, only very few triply bonded compounds that contain a nitrogen element (i.e., L–B N–L,66–69 L–Ga N–L,70,71 and L–In N–L70) have been successfully synthesized and isolated. No other triple bond molecules containing aluminum (L–Al N–L) and thallium (L–Tl N–L) have been both experimentally and theoretically reported.

Although the authors have already published 14 papers concerning group 13 group 15 triple bond molecules,52–65 the present computational evidence demonstrates that the results about the stability of the triply bonded RE13 NR compounds are quite different from our previous theoretical examinations. For instance, the theoretical conclusions based on our previous papers show that only the bulky ligands can stabilize the triply bonded L–E13 E15–L (E15 = P, As, Sb, and Bi) molecules.52–65 Nevertheless, in this work, the authors' computations in this work reveal that both small (but electropositive) ligands and bulky substituents can effectively stabilize the triply bonded L–E13 N–L compounds. In other words, the present theoretical evidences emphasize that both small (but electropositive) substituents and sterically bulky groups can successfully protect the central triple bond, which, in turn, can increase the bond order of this triple bond. Because of the difficulties in experimentally synthesizing these rare triply bonded molecules, this study theoretically determines the effect of substituents on the formation of L–E13 N–L featuring a triple bond. The geometrical structures and associated properties of stable L–E13 N–L molecules are theoretically predicted. Accordingly, the present work can conduct the experimental chemists how to design and synthesize the triply bonded RE13 NR compounds using the effective way.

2. General considerations

In order to determine the valence electronic structures of L–E13 N–L, similarly to our previous studies,50–64 the L–E13 N–L species is divided into two fragments: L–E13 and L–N. These are shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. The valence-bond bonding mechanisms [A] and [B] for the triply bonded L–E13 N–L molecule: ΔE1 = E(triplet state for R–N) − E(singlet state for R–N) and ΔE2 = E(triplet state for R–E13) − E(singlet state for R–E13).

As seen in Fig. 1, there are two mechanisms for the formation of the L–E13 N–L triple bond species at the singlet ground state. The choice of mechanism [A] or mechanism [B] respectively depends on the promotion energy of L–N and L–E13 moieties. For mechanism [A], a singlet L–E13 and a singlet L–N combine to yield a singlet L–E13 N–L molecule, which is named a singlet–singlet bonding ([L–E13]1 + [L–N]1 → [L–E13 N–L]1). For mechanism [B], a triplet L–E13 and a triplet L–N couple to yield a singlet L–E13 N–L compound, which is called a triplet–triplet bonding ([L–E13]3 + [L–N]3 → [L–E13 N–L]1).

The chemical bonding nature of mechanism [A] in Fig. 1 contains three types of chemical bonds: a valence lone pair orbital of E13 → a valence p orbital of N, a valence p orbital of E13 ← a valence lone pair orbital of N, and a valence p orbital of E13 ← a valence p orbital of N. In other words, the E13

N triple bond features one E13 → N σ donation bond and two E13 ← N π donation bonds. Therefore, the central E13

N triple bond in mechanism [A] can be regarded as L–E13 N–L.

N–L.

For mechanism [B], the chemical bonding character of the E13

N triple bond in Fig. 1 involves three types of chemical bonds: a valence lone pair orbital of E13 — a valence p orbital of N, a valence p orbital of E13 — a valence p orbital of N, and a valence p orbital of E13 ← a valence lone pair orbital of N. The E13

N triple bond features one traditional E13–N σ bond, one traditional E13–N π bond and one E13 ← N π donation bond. Therefore, the principal E13

N triple bond in mechanism [B] can be described as L–E13 N–L. The two non-degenerate π bonding orbitals (π⊥ and π‖) for H–B

N–H are schematically represented in Fig. 2.

N–L. The two non-degenerate π bonding orbitals (π⊥ and π‖) for H–B

N–H are schematically represented in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. The natural B N π bonding orbitals (π⊥ and π‖ for (a) and (b), respectively) for H–B N–H, based on Fig. 1.

It is noteworthy that, as demonstrated in Fig. 1, the vital bonding in the triply bonded L–E13 N–L species contributes greatly to the lone pair of the N–L moiety, whose electron pair is donated to the empty p–π orbital of the L–E13 component. In particular, the lone pair orbital of the N–L unit includes the s valence orbital of nitrogen. The atomic size of E13 is also apparently different from that of nitrogen, especially for the E13 elements with a higher atomic number. Therefore, the overlap in the orbital populations between E13 and nitrogen is expected to be small. That is to say, from the overlap population viewpoint, this theoretical analysis anticipates that the triple bond between E13 and N must be weak. This prediction is verified in the following discussion.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Small ligands on substituted L–E13 N–L

The effect of small ligands L (=F, OH, H, CH3 and SiH3) on the stability of the triply bonded L–B N–L molecules is determined. For comparison, three computational methods (M06-2X/Def2-TZVP, B3PW91/Def2-TZVP, and B3LYP/LANL2DZ+dp), based on density functional theory (DFT), are used to determine the relative stability of the doubly bonded L2B N: and :B NL2 and the triply bonded L–B N–L. The calculated potential energy surfaces are schematically shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. The relative Gibbs free energy for L–B N–L (L = F, OH, H, CH3, and SiH3) calculated at the M06-2X/Def2-TZVP, B3PW91/Def2-TZVP, and B3LYP/LANL2DZ+dp levels of theory. For details see the text and Table 1.

Interestingly, unlike the other L–E13 E15–L molecular systems that have been previously studied,50–64 the theoretical data for this study using three DFT methods suggest that when ligands are small and electropositive, the triply bonded L–B N–L molecule could be experimentally produced and detected, since these triple bonded species are more thermodynamically stable than their corresponding doubly bonded L2B N: and :B NR2 isomers. Actually, these triply bonded L–B N–L species, which is isoelectronic to the alkynes L–C C–L and which contain small and electropositive substituents were experimentally isolated and structurally characterized about three decades ago.65–68

Several important geometrical parameters and the associated physical properties of L–B N–L (Table 1), L–Al N–L (Table S1†), L–Ga N–L (Table S2†), L–In N–L (Table S3†) and L–Tl N–L (Table S4†) are listed in ESI.†

The important geometrical parameters, the Wiberg bond index (WBI), the natural charge densities (QB and QN), the HOMO–LUMO energy gaps, the singlet–triplet energy splitting (ΔEB and ΔEN), and the binding energies (BE) for L–B N–L using the B3PW91/Def2-TZVP, M06-2X/Def2-TZVP (in round bracket), and B3LYP/LANL2DZ+dp (in square bracket) levels of theory.

| L | F | OH | H | CH3 | SiH3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B N (Å) | 1.275 | 1.276 | 1.246 | 1.249 | 1.262 |

| (1.245) | (1.254) | (1.233) | (1.239) | (1.252) | |

| [1.220] | [1.238] | [1.231] | [1.236] | [1.248] | |

| ∠L–B–N (°) | 165.4 | 169.1 | 180.0 | 180.0 | 180.0 |

| (169.1) | (170.7) | (180.0) | (180.0) | (180.0) | |

| [180.0] | [174.1] | [179.9] | [179.9] | [178.6] | |

| ∠B–N–L (°) | 137.3 | 137.0 | 180.0 | 180.0 | 180.0 |

| (151.4) | (146.5) | (180.0) | (180.0) | (179.9) | |

| [160.0] | [158.2] | [179.9] | [179.9] | [178.9] | |

| ∠L–B–N–L (°) | 180.0 | 163.5 | 163.0 | 180.0 | 169.1 |

| (179.9) | (161.9) | (169.3) | (178.7) | (176.9) | |

| [180.0] | [159.7] | [178.8] | [178.4] | [172.1] | |

| Q B a | 0.2569 | 0.0441 | 0.1196 | −0.1350 | −0.2670 |

| (0.1543) | (−0.0515) | (−0.1194) | (−0.2172) | (−0.1986) | |

| [0.1335] | [−0.0465] | [−0.0817] | [−0.2570] | [−0.2213] | |

| Q N b | 0.1573 | 0.1411 | −0.2376 | −0.1295 | −0.0263 |

| (0.2340) | (0.1185) | (−0.2197) | (−0.1512) | (−0.0584) | |

| [0.2253] | [0.1226] | [−0.2575] | [−0.1150] | [−0.0537] | |

| ΔEST for L–Bc (kcal mol−1) | 73.97 | 64.90 | 25.39 | 36.79 | 22.28 |

| (73.60) | (62.12) | (27.65) | (32.69) | (21.77) | |

| [81.01] | [68.97] | [28.74] | [38.47] | [22.33] | |

| ΔEST for L–Nd (kcal mol−1) | −46.00 | −21.39 | −50.89 | 46.76 | 44.87 |

| (−48.48) | (−21.68) | (−55.08) | (48.23) | (46.86) | |

| [−45.47] | [−19.91] | [−49.44] | [50.99] | [48.02] | |

| HOMO–LUMO (kcal mol−1) | 147.8 | 128.3 | 197.6 | 162.2 | 165.6 |

| (173.2) | (145.9) | (206.1) | (182.3) | (165.4) | |

| [242.5] | [203.2] | [265.7] | [228.3] | [224.4] | |

| BEe (kcal mol−1) | 149.7 | 168.2 | 200.1 | 188.8 | 206.2 |

| (147.5) | (166.1) | (202.4) | (190.3) | (208.4) | |

| [157.4] | [171.4] | [210.5] | [199.4] | [217.4] | |

| WBIf | 1.880 | 1.843 | 2.114 | 1.962 | 1.908 |

| (1.951) | (1.911) | (2.149) | (2.000) | (1.963) | |

| [1.988] | [1.938] | [2.128] | [2.000] | [1.960] |

The natural charge density on B.

The natural charge density on N.

ΔEST = E(triplet state for L–B) − E(singlet state for L–B).

ΔEST = E(triplet state for L–N) − E(singlet state for L–N).

BE = E(singlet state for L–B) + E(singlet state for L–B) – E(singlet state for L–B N–L).

The Wiberg bond index (WBI) for the B N bond: see ref. 71 and 72.

As shown in Table 1, these computations predict that the B N triple bond distance (Å) lies in the range, 1.246–1.276 (B3PW91/Def2-TZVP), 1.233–1.254 (M06-2X/Def2-TZVP) and 1.220–1.248 (B3LYP/LANL2DZ+dp). The reported experimental values for the B N triple bond length are 1.240 Å (ref. 65 and 66) and 1.258 Å,67,68 which agree well with the theoretical data for this study.

In the case of the ΔEST (=E(triplet state) − E(singlet state)) for the L–B fragment (Table 1), its excited energy from the singlet ground state to the triplet excited state is theoretically estimated to be at least 22 kcal mol−1. However, for the L–N moiety, the modulus advancement energy between the ground state and the first excited state is calculated to be at least 20 kcal mol−1. On the basis of the theoretical analysis in Section 2, this theoretical data shows that mechanism [A] is feasible for the interpretation of the generation of the triply bonded L–B

N–L species that feature small ligands. Therefore, the bonding disposition of L–B

N–L with small substituents must be viewed as L–B N–L, so one B → N σ donation bond and two B ← N π donation bonds constitute the B

N triple bond. All the values for the Wiberg bond index (WBI)71,72 in Table 1 show that B

N bonds that are supported by small groups have values of less than 2.1, but the WBI for the C

C bond in ethyne is 2.99. These L–B

N–L species that feature small substituents have a bond order of much less than 2.00 for the central B–N bond, as shown in Table 1. One explanation for this is that, as shown in Fig. 1, the lone pair orbitals of both the L–B and L–N components contain the valence s characters. This significantly decreases the bonding strength between boron and nitrogen. It is also possible that the covalent radii of boron and nitrogen, at 82 pm and 70 pm,73 result in a small overlapping population between B and N, which could result in small WBI values.

N–L, so one B → N σ donation bond and two B ← N π donation bonds constitute the B

N triple bond. All the values for the Wiberg bond index (WBI)71,72 in Table 1 show that B

N bonds that are supported by small groups have values of less than 2.1, but the WBI for the C

C bond in ethyne is 2.99. These L–B

N–L species that feature small substituents have a bond order of much less than 2.00 for the central B–N bond, as shown in Table 1. One explanation for this is that, as shown in Fig. 1, the lone pair orbitals of both the L–B and L–N components contain the valence s characters. This significantly decreases the bonding strength between boron and nitrogen. It is also possible that the covalent radii of boron and nitrogen, at 82 pm and 70 pm,73 result in a small overlapping population between B and N, which could result in small WBI values.

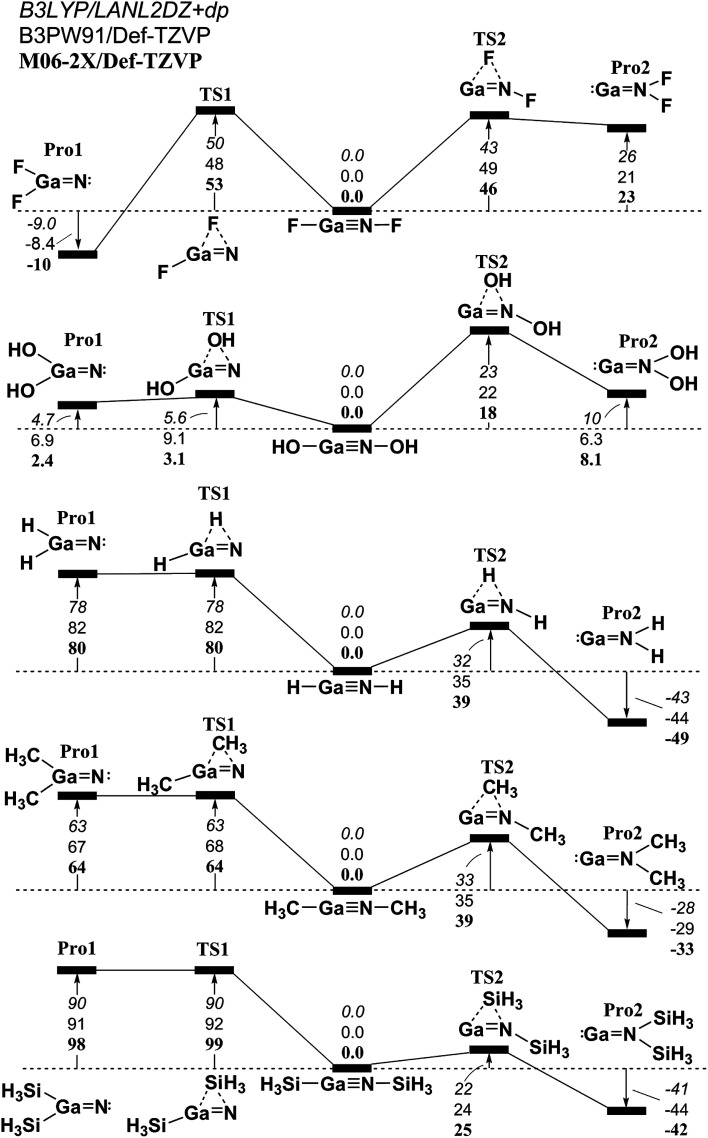

Similar to the 1,2-migration reactions for L–B N–L, the potential energy surfaces for the other triply bonded L–Al N–L, L–Ga N–L, L–In N–L and L–Tl N–L compounds are schematically represented in Fig. 4–7, respectively. Being close to the L–B N–L (Fig. 3) compound, the computational results for the 1,2-ligand-shift reactions show that either a proton or the ligands containing the carbon atom (such as CH3) stabilize the triply bonded L–E13 N–L (E13 = Al, Ga, In and Tl) species relative to their corresponding double-bond isomers. This theoretical finding is quite different from those for the other L–E13 E15–L systems that have been previously studied,52–64 in which regardless of whether the small ligands are electronegative or electropositive, the triple-bond L–E13 E15–L (except for E15 = N) compounds are not thermodynamically stable in the 1,2-migration reactions. To the authors' best knowledge, both monomeric imides Ar′–M N–Ar′′ (M = Ga or In; Ar′ or Ar′′ = terphenyl ligands) that were reported by Power and co-workers have been successfully synthesized and structurally characterized.69,70 The computed geometrical parameters and some physical properties of the L–E13 N–L (E13 = Al, Ga, In and Tl) molecules featuring small groups are listed in Tables S1, S2, S3, and S4,† respectively. Several important conclusions can be drawn from Tables S1–S4.†

Fig. 4. The relative Gibbs free energy for L–Al N–L (L = F, OH, H, CH3, and SiH3) calculated at the M06-2X/Def2-TZVP, B3PW91/Def2-TZVP, and B3LYP/LANL2DZ+dp levels of theory. For details see the text and Table S1.†.

Fig. 5. The relative Gibbs free energy for L–Ga N–L (L = F, OH, H, CH3, and SiH3) calculated at the M06-2X/Def2-TZVP, B3PW91/Def2-TZVP, and B3LYP/LANL2DZ+dp levels of theory. For details see the text and Table S2.†.

Fig. 6. The relative Gibbs free energy for L–In N–L (L = F, OH, H, CH3, and SiH3) calculated at the M06-2X/Def2-TZVP, B3PW91/Def2-TZVP, and B3LYP/LANL2DZ+dp levels of theory. For details see the text and Table S3.†.

Fig. 7. The relative Gibbs free energy for L–Tl N–L (L = F, OH, H, CH3, and SiH3) calculated at the M06-2X/Def2-TZVP, B3PW91/Def2-TZVP, and B3LYP/LANL2DZ+dp levels of theory. For details see the text and Table S4.†.

(1) It is noteworthy that according to the available experimental detections, the lengths of the Ga N (1.701 Å)69,70 and In N (1.928 Å)69 triple bonds are consistent with the computational results (1.662–1.804 Å and 1.828–2.073 Å) in Tables S2 and S3,† respectively. This theoretical evidence strongly suggests that the computational methods that are used in this study provide reliable information for further theoretical observations.

(2) The results using DFT that are shown in Table S1† (L–Al N–L) and Table S4† (L–Tl N–L) predict that the central Al N and Tl N bond distances are in the range, 1.608–1.753 Å and 1.849–2.300 Å, respectively. The calculated WBI for the central Al–N, Ga–N, In–N, and Tl–N bonds are all estimated to be less than 1.50. This theoretical evidence strongly suggests that all of these central triple bonds in L–E13 N–L molecules that feature small substituents must be quite weak, possibly because of the hybridized lone pair orbitals for both L–E13 and L–N fragments and the different atomic radius for E13 and N elements, both of which do not produce good overlap populations between nitrogen and the group 13 elements.

(3) The DFT data in Tables S1–S4† shows that the singlet–triplet energy splitting (ΔEST) for the L–E13 fragment is much higher than that for the L–N moiety. Therefore, the electron for the latter jumps from the triplet ground state to the singlet excited state more easily than the electron from the singlet ground state for the former. As a result, it is better to use mechanism [A] to describe the bonding characteristic of the L–E13

N–L molecule bearing the small substituents. For mechanism [A] in Fig. 1, the bonding constitution for the E13

N triple bond in L–E13

N–L that feature small ligands must be L–E13 N–L.

N–L.

3.2. Large ligands on substituted L′–E13 N–L′

The possibility of bulky substituents (L′) stabilizing the central E13 N triple bond is determined. Similarly to previous studies,52–64 as shown in Scheme 1, SiMe(SitBu3)2, SiiPrDis2, Tbt and Ar* are used for this study. London dispersion forces, which are the non-valent interactions between large groups, can greatly affect the structure and stability of sterically congested molecules.74 Therefore, the dispersion-corrected M06-2X/Def2-TZVP method75 is used to gain more information about producing stable, triple-bonded L′–E13 N–L′ species. The key geometrical parameters and the associated physical properties of L′–B N–L′ are listed in Table 2. This information for other triply bonded molecules that feature bulky ligands, i.e., L′–Al N–L′ (Table S5†), L′–Ga N–L′ (Table S6†), L′–In N–L′ (Table S7†), and L′–Tl N–L′ (Table S8†), is collected in ESI.†

Scheme 1.

The bond lengths (Å), bond angles (°), singlet–triplet energy splitting  natural charge densities

natural charge densities  binding energies (BE), the Wiberg bond index (WBI), HOMO–LUMO energy gaps, and some reaction enthalpies for L′–B

N–L′ at the M06-2X/Def2-TZVP level of theory.

binding energies (BE), the Wiberg bond index (WBI), HOMO–LUMO energy gaps, and some reaction enthalpies for L′–B

N–L′ at the M06-2X/Def2-TZVP level of theory.

| L′ | SiMe(SitBu3)2 | SiiPrDis2 | Tbt | Ar* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B N (Å) | 1.257 | 1.242 | 1.273 | 1.267 |

| ∠L′–B–N (°) | 175.2 | 165.2 | 171.9 | 171.2 |

| ∠B–N–L′ (°) | 163.1 | 166.6 | 157.7 | 166.2 |

| ∠L′–B–N–L′ (°) | 180.0 | 180.0 | 178.7 | 179.5 |

a

a

|

0.2413 | 0.0818 | −0.2133 | −0.1600 |

b

b

|

−0.3076 | −0.4369 | −0.1566 | −0.1471 |

for L′–Bc (kcal mol−1) for L′–Bc (kcal mol−1) |

13.59 | 11.24 | 21.47 | 20.75 |

| ΔEST for L′–Nd (kcal mol−1) | −22.30 | −25.05 | −25.52 | −28.63 |

| HOMO–LUMO (kcal mol−1) | 103.3 | 114.2 | 66.97 | 68.28 |

| BEe (kcal mol−1) | 380.0 | 383.8 | 375.9 | 426.3 |

| ΔH1f (kcal mol−1) | 98.78 | 80.03 | 91.69 | 89.84 |

| ΔH2f (kcal mol−1) | 94.05 | 71.21 | 92.96 | 75.25 |

| WBIg | 2.188 | 2.161 | 2.078 | 2.135 |

The natural charge density on boron.

The natural charge density on nitrogen.

(kcal mol−1) = E(triplet state for L′–B) − E(singlet state for L′–B).

(kcal mol−1) = E(triplet state for L′–B) − E(singlet state for L′–B).

(kcal mol−1) = E(triplet state for L′–N) − E(singlet state for L′–N).

(kcal mol−1) = E(triplet state for L′–N) − E(singlet state for L′–N).

BE (kcal mol−1) = E(triplet state for L′–B) + E(triplet state for L′–N) − E(singlet for L′–B N–L′).

See Scheme 2.

The Wiberg bond index (WBI) for the B N bond: see ref. 71 and 72.

The same computational method is used to determine the 1,2-ligand-shift reactions for L′–E13 N–L′ molecules that are substituted with bulky groups; i.e., L′–E13 N–L′ → L2′E13 N: and L′–E13 N–L′ →:E13 NL2′, as shown in Scheme 2. The results in Table 2 show that because of steric crowding, the potential energies of both double-bond molecules (:B NL2′ and L2′B N) are respectively higher than that of the corresponding triple-bond L′–B N–L′ isomer by at least 80 and 71 kcal mol−1. These theoretical findings strongly suggest that sterically hindered ligands shield the central weak B N triple bond, since the Wiberg bond index (WBI) for the C C bond in acetylene was computed to be 2.99.

Scheme 2.

The computational data in Tables 2 and S5–S8† shows that the central triple bond distances are predicted to be in the range of 1.242–1.273 Å (L′–B N–L′), 1.681–1.719 Å (L′–Al N–L′), 1.698–1.722 Å (L′–Ga N–L′), 1.866–1.902 Å (L′–In N–L′), and 1.877–1.930 Å (L′–Tl N–L′). These predicted bond lengths are consistent with other reported experimental data, such as, 1.240 Å (ref. 65 and 66) and 1.258 Å (ref. 67 and 68) for the B N bond, 1.701 Å (ref. 69 and 70) for the Ga N bond and 1.928 Å (ref. 69) for the In N bond. Since there is good agreement between the available experimental values and the dispersion-corrected M06-2X data for the central triple bond lengths, the computational method that is used in this study must be reliable.

The M06-2X results in Table 2 show that the  for the L′–B fragment is calculated to be at least 11 kcal mol−1, but the modulus of

for the L′–B fragment is calculated to be at least 11 kcal mol−1, but the modulus of  for the L′–N component is computed to be at least 22 kcal mol−1. In other words, L′–B jumps easily from the singlet ground state to the triplet state because the

for the L′–N component is computed to be at least 22 kcal mol−1. In other words, L′–B jumps easily from the singlet ground state to the triplet state because the  value for L′–B is smaller than that for L′–N. Therefore, the L′–B and L′–N fragments must follow a triplet–triplet bonding mechanism; i.e., mechanism [B]: [L′–B]3 + [L′–N]3 → [L′–B

N–L′]1. As schematically shown in Fig. 1, the bonding nature of the bulkily substituted L′–B

N–L′ can be viewed as L′–B

value for L′–B is smaller than that for L′–N. Therefore, the L′–B and L′–N fragments must follow a triplet–triplet bonding mechanism; i.e., mechanism [B]: [L′–B]3 + [L′–N]3 → [L′–B

N–L′]1. As schematically shown in Fig. 1, the bonding nature of the bulkily substituted L′–B

N–L′ can be viewed as L′–B N–L′. That is to say, this B

N triple bond consists of a usual σ bond, a conventional π bond and a donor–acceptor π bond.

N–L′. That is to say, this B

N triple bond consists of a usual σ bond, a conventional π bond and a donor–acceptor π bond.

However, each lone-pair orbital of L′–B and L′–N respectively contains s and p valence orbitals of boron and nitrogen. As shown in Fig. 1, this phenomenon means that the overlap population between L′–B and L′–N is small. Therefore, the bond order for the B

N triple bond must be small. This study's M06-2X computations are shown in Table 2 and confirm this prediction. Similarly, the values for  for L′–N and the other L′–B fragments in Tables S5–S8† show that the modulus of

for L′–N and the other L′–B fragments in Tables S5–S8† show that the modulus of  (>22 kcal mol−1) for the former is always larger than those for the latter, e.g., L′–Al (>18 kcal mol−1), L′–Ga (>15 kcal mol−1), L′–In (>17 kcal mol−1) and L′–Tl (>19 kcal mol−1). These computational values show that all of the bonding in these triply bonded L′–E13

N–L′ species can be represented as L′–E13

(>22 kcal mol−1) for the former is always larger than those for the latter, e.g., L′–Al (>18 kcal mol−1), L′–Ga (>15 kcal mol−1), L′–In (>17 kcal mol−1) and L′–Tl (>19 kcal mol−1). These computational values show that all of the bonding in these triply bonded L′–E13

N–L′ species can be represented as L′–E13 N–L′.

N–L′.

The theoretically calculated values for the 1,2-shifted energy barriers and the B N bond orders (WBI) in Table 2 strongly indicate that large substituents protect the central fragile B N triple bond and increase its bond order. The same conclusions can also be drawn from the computational results for the other triply bonded L′–E13 N–L′ molecules, which are listed in Tables S5–S8.†

Both natural bond orbital (NBO)71,72 and natural resonance theory (NRT)76–78 are used to determine the electronic densities of the triply bonded L′–B N–L′ molecules that feature large substituents. The M06-2X results are listed in Table 3. The same theoretical analysis for the other triply bonded L′–E13 N–L′ species is listed in ESI:† L′–Al N–L′ (Table S9†), L′–Ga N–L′ (Table S10†), L′–In N–L′ (Table S11†), and L′–Tl N–L′ (Table S12†). The NRT values in Table 3 show that the bond order for the B N bond is 2.18 (L′ = SiMe(SitBu3)2), 2.17 (L′ = SiiPrDis2), 2.24 (L′ = Tbt), and 2.22 (L′ = Ar*). This NRT data is similar to the WBI values (2.19, 2.16, 2.08, and 2.14, respectively) in Table 3. The NBO and NRT data in Table 3 also shows that the triply bonded L′–B N–L′ molecules for this study all have an analogous electronic structure. As seen in Table 3, (SiMe(SitBu3)2)–B N–(SiMe(SitBu3)2) is predicted to have one σ bond and two π (π⊥ and π‖) bonds, which are occupied by two electrons: that is, 1.99 (σ), 1.96 (π⊥) and 1.96 (π‖). The M06-2X results also show that the σ bond is heavily polarized towards nitrogen (78%) and that there are two non-degenerate π bonds that are also heavily polarized towards nitrogen (π⊥, 80% and π‖, 80%). This is consistent with the fact that nitrogen (3.066) is more electronegative than boron (2.051).79 The two non-degenerate π bonding orbitals (π⊥ and π‖) are schematically given in ESI.†

The natural bond orbital (NBO) and natural resonance theory (NRT) analysis for L′–B N–R′ molecules that feature bulky ligands (L′ = SiMe(SitBu3)2, Tbt, SiiPrDis2, and Ar*) at the M06-2X/Def2-TZVP level of theorya,b.

| L′–B N–R′ | WBI | NBO analysis | NRT analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Occupancy | Hybridization | Polarization | Total/covalent/ionic | Resonance weight | ||

| L′ = SiMe(SitBu3)2 | 2.19 | σ: 1.99 | σ: 0.4743 B (sp1.43) + 0.8803 N (sp0.80) | 22.50% (B) | 2.18/0.88/1.30 | B–N: 6.14% |

| 77.50% (N) | ||||||

| B N: 69.80% | ||||||

| π⊥: 1.96 | π⊥: 0.4506 B (sp99.99) + 0.8927 N (sp99.99) | 20.30% (B) | ||||

| B N: 24.06% | ||||||

| 79.70% (N) | ||||||

| π‖: 1.96 | π‖: 0.4483 B (sp99.99) + 0.8939 N (sp1.00) | 20.10% (B) | ||||

| 79.90% (N) | ||||||

| L′ = SiiPrDis2 | 2.16 | σ: 1.99 | σ: 0.4747 B (sp1.44) + 0.8801 N (sp0.83) | 22.54% (B) | 2.17/0.91/1.26 | B–N: 72.26% |

| 77.46% (N) | B N: 27.74% | |||||

| π⊥: 1.96 | π⊥: 0.4530 B (sp99.99) + 0.8915 N (sp99.99) | 20.52% (B) | ||||

| B N: 0.00% | ||||||

| 79.48% (N) | ||||||

| π‖: 1.96 | π‖: 0.4430 B (sp21.83) + 0.8965 N (sp79.29) | 19.63% (B) | ||||

| 80.37% (N) | ||||||

| L′ = Tbt | 2.08 | σ: 1.99 | σ: 0.4855 B (sp1.34) + 0.8742 N (sp0.81) | 23.57% (B) | 2.24/0.49/1.75 | B–N: 81.96 |

| 76.43% (N) | ||||||

| B N: 18.04 | ||||||

| π⊥: 1.94 | π⊥: 0.4515 B (sp99.99) + 0.8923 N (sp1) | 20.38% (B) | ||||

| B N: 0.00% | ||||||

| 79.62% (N) | ||||||

| π‖: 1.88 | π‖: 0.4433 B (sp99.99) + 0.8964 N (sp99.99) | 19.65% (B) | ||||

| 80.35% (N) | ||||||

| L′ = Ar* | 2.14 | σ: 1.99 | σ: 0.4918 B (sp1.30) + 0.8707 N (sp0.84) | 24.18% (B) | 2.22/0.49/1.09 | B–N: 42.68% |

| 75.82% (N) | ||||||

| B N: 56.9% | ||||||

| π⊥: 1.95 | σ: 0.4580 B (sp99.99) + 0.8889 N (sp99.99) | 20.98% (B) | ||||

| B N: 0.42% | ||||||

| 79.02% (N) | ||||||

| π‖: 1.85 | σ: 0.4433 B (sp99.99) + 0.8964 N (sp99.99) | 19.65% (B) | ||||

| 80.35% (N) | ||||||

The value of the Wiberg bond index (WBI) for the B N bond and the occupancy of the corresponding σ and π bonding NBO (see ref. 71 and 72).

NRT; see ref. 76–78.

4. Conclusions

This study uses DFT computational methods to determine the effect of both small and bulky substituents on the triple-bonded L–E13 N–L (E13 = B, Al, Ga, In, and Tl) compounds, in order to determine how to successfully design and synthesize a molecule featuring an E13 N triple bond. This study represents the first theoretical investigation of the stability of the triply bonded L–E13 N–L molecules. Four important conclusions are drawn, based on the results of this theoretical study:

(1) Previous theoretical conclusions52–64 showed that only sterically bulky ligands, and not small groups, thermodynamically stabilize the triple bond of the L–E13 E15–L (E13 = B, Al, Ga, In and Tl; E15 = P, As, Sb and Bi) molecules. However,52–64 this theoretical study finds that both small (but electropositive) ligands and bulky substituents stabilize the triply bonded L–E13 N–L compounds.

(2) The theoretical analysis shows that the bonding nature of a triply bonded L–E13

N–L molecule that features small substituents can be represented as L–E13 N–L.

N–L.

(3) The bonding character of the central triple bond in an L′–E13

N–L′ compound that features bulkier substituents can be regarded as L′–E13 N–L′.

N–L′.

(4) Since two central heteroatoms (E13 and N) are involved in the triply bonded L–E13 N–L (and L′–E13 N–L′) species, they belong to different rows of the periodic table so they have different quantum numbers. Therefore, E13 and N have different electronegativity values and different atomic sizes. Due to the poor overlap populations between E13 and N in both triply bonded L–E13 N–L and L′–E13 N–L′ molecules, it is expected that the bond order of the E13 N triple bond must be small, so their E13 N triple bonds must be weak.

The results of this theoretical study should allow the production and synthesis of stable triply bonded L–E13 N–L and L′–E13 N–L′ molecules.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the National Center for High-Performance Computing in Taiwan for the donation of generous amounts of computing time. The authors are also grateful for financial support from the Ministry of Science and Technology of Taiwan. Special thanks are also due to reviewers 1 and 2 for very help suggestions and comments.

Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available. See DOI: 10.1039/c9ra00318e

References

- Power P. P. Boron-Phosphorus Compounds and Multiple Bonding. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1990;29:449–460. doi: 10.1002/anie.199004491. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Power P. P. Moezzi A. Pestana D. C. Petrie M. A. Shoner S. C. Waggoner K. M. Multiple Bonding, π-bonding Contributions and Aromatic Character in Isoelectronic Boron-phosphorus, Boron-arsenic, Aluminum-nitrogen and Zinc-sulfur Compounds. Pure Appl. Chem. 1991;63:859–866. [Google Scholar]

- Paine R. T. Nöth H. Recent Advances in Phosphinoborane Chemistry. Chem. Rev. 1995;95:343–379. doi: 10.1021/cr00034a003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Okazaki R. West R. Chemistry of Stable Disilenes. Adv. Organomet. Chem. 1996;39:231–273. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3055(08)60469-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Power P. P. π-Bonding and the Lone Pair Effect in Multiple Bonds between Heavier Main Group Elements. Chem. Rev. 1999;99:3463–3504. doi: 10.1021/cr9408989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robison G. H. Gallanes, Gallenes, Cyclogallenes, and Gallynes: Organometallic Chemistry about the Gallium-Gallium Bond. Acc. Chem. Res. 1999;32:773–782. doi: 10.1021/ar980135y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haaf M. Schmedake T. A. West R. Stable Silylenes. Acc. Chem. Res. 2000;33:704–714. doi: 10.1021/ar950192g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehrhus B. Lappert M. F. Chemistry of Thermally Stable Bis(amino)silylenes. J. Organomet. Chem. 2001;617:209–223. doi: 10.1016/S0022-328X(00)00729-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weidenbruch M. Triple Bonds of the Heavy Main-Group Elements: Acetylene and Alkylidyne Analogues of Group 14. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2003;42:2222–2224. doi: 10.1002/anie.200301635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gusel’nikov L. E. Hetero-π-systems from 2+2 Cycloreversions. Part 1. Gusel'nikov-Flowers Route to Silenes and Origination of the Chemistry of Doubly Bonded Silicon. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2003;244:149–204. doi: 10.1016/S0010-8545(03)00104-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weidenbruch M. From a Cyclotrisilane to a Cyclotriplumbane: Low Coordination and Multiple Bonding in Group 14 Chemistry. Organometallics. 2003;22:4348–4360. doi: 10.1021/om034085z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Power P. P. Silicon, Germanium, Tin and Lead Analogues of Acetylenes. Chem. Commun. 2003:2091–2101. doi: 10.1039/B212224C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lein M. Krapp A. Frenking G. Why Do the Heavy-Atom Analogues of Acetylene E2H2 (E = Si−Pb) Exhibit Unusual Structures? J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:6290–6299. doi: 10.1021/ja042295c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehrhus B. Hitchcock P. B. Pongtavornpinyo R. Zhang L. Insights Into the Making of a Stable Silylene. Dalton Trans. 2006;15:1847–1857. doi: 10.1039/B514666F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekiguchi A. Ichinohe M. Kinjo R. The Chemistry of Disilyne with a Genuine Si–Si Triple Bond: Synthesis, Structure, and Reactivity. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 2006;79:825–832. doi: 10.1246/bcsj.79.825. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kira M. Iwamoto T. Ishida S. A Helmeted Dialkylsilylene. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 2007;80:258–275. doi: 10.1246/bcsj.80.258. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. Robinson G. H. Organometallics of the Group 13 M-M Bond (M = Al, Ga, In) and the Concept of Metalloaromaticity. Organometallics. 2007;26:2–11. doi: 10.1021/om060737i. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Power P. P. Bonding and Reactivity of Heavier Group 14 Element Alkyne Analogues. Organometallics. 2007;26:4362–4372. doi: 10.1021/om700365p. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sekiguchi A. Disilyne With a Silicon-Silicon Triple Bond: A New Entry to Multiple Bond Chemistry. Pure Appl. Chem. 2008;80:447–457. [Google Scholar]

- Sekiguchi A. Kinjo R. Ichinohe M. Interaction of π-bonds of the Silicon-Silicon Triple Bond with Alkali Metals: An Isolable Anion Radical Upon Reduction of a Disilyne. Synth. Met. 2009;159:773–775. doi: 10.1016/j.synthmet.2009.01.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scheschkewitz D. Anionic Reagents with Silicon-Containing Double Bonds. Chem. - Eur. J. 2009;15:2476–2485. doi: 10.1002/chem.200801968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. Robinson G. H. Unique Homonuclear Multiple Bonding in Main Group Compounds. Chem. Commun. 2009:5201–5213. doi: 10.1039/B908048A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer R. C. Power P. P. π-Bonding and the Lone Pair Effect in Multiple Bonds Involving Heavier Main Group Elements: Developments in the New Millennium. Chem. Rev. 2010;110:3877–3923. doi: 10.1021/cr100133q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kira M. An isolable dialkylsilylene and its derivatives. A step toward comprehension of heavy unsaturated bonds. Chem. Commun. 2010;46:2893–2903. doi: 10.1039/C002806A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasamori T. Han J. S. Hironaka K. Takagi N. Nagase S. Tokitoh N. Synthesis and Structure of Stable 1,2-Diaryldisilyne. Pure Appl. Chem. 2010;82:603. [Google Scholar]

- Peng Y. Fischer R. C. Merrill W. A. Fischer J. Pu L. Ellis B. D. Fettinger J. C. Herber R. H. Power P. P. Substituent Effects in Ditetrel Alkyne Analogues: Multiple vs. Single Bonded Isomers. Chem. Sci. 2010;1:461–468. doi: 10.1039/C0SC00240B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sekiguchi A. Kinjo R. Ichinohe M. A Stable Compound Containing A Silicon-Silicon Triple Bond. Science. 2004;305:1755–1757. doi: 10.1126/science.1102209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiberg N. Vasisht S. K. Fischer G. Mayer P. Disilynes. III [1] a Relatively Stable Disilyne RSi≡SiR (R = SiMe(SitBu3)2) Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 2004;630:1823–1828. doi: 10.1002/zaac.200400177. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sasamori T. Hironaka K. Sugiyama T. Takagi N. Nagase S. Hosoi Y. Furukawa Y. Tokitoh N. Synthesis and Reactions of a Stable 1,2-diaryl-1,2-dibromodisilene: A Precursor for Substituted Disilenes and 1,2-diaryldisilyne. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:13856–13857. doi: 10.1021/ja8061002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stender M. Phillips A. D. Wright R. J. Power P. P. Synthesis and Characterization of a Digermanium Analogue of an Alkyne. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2002;41:1785–1787. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020517)41:10<1785::AID-ANIE1785>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stender M. Phillips A. D. Power P. P. Formation of [Ar*Ge{CH2C(Me)C(Me)CH2}CH2C(Me)N]2 (Ar* = C6H3-2,6-Trip2; Trip = C6H2-2,4,6-i-Pr3) Via Reaction of Ar*GeGeAr* with 2,3-dimethyl-1,3-butadiene: Evidence for the Existence of a Germanium Analogue of an Alkyne. Chem. Commun. 2002:1312–1313. doi: 10.1039/B203403D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pu L. Phillips A. D. Richards A. F. Stender M. Simons R. S. Olmstead M. M. Power P. P. Germanium and Tin Analogues of Alkynes and Their Reduction Products. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:11626–11636. doi: 10.1021/ja035711m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiyama Y. Sasamori T. Hosoi Y. Furukawa Y. Takagi N. Nagase S. Tokitoh N. Synthesis and Properties of a New Kinetically Stabilized Digermyne: New Insights for a Germanium Analogue of an Alkyne. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:1023–1031. doi: 10.1021/ja057205y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spikes G. H. Power P. P. Lewis Base Induced Tuning of the Ge–Ge Bond Order in a ‘‘digermyne’’. Chem. Commun. 2007:85–87. doi: 10.1039/B612202G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips A. D. Wright R. J. Olmstead M. M. Power P. P. Synthesis and Characterization of 2,6-Dipp2-H3C6SnSnC6H3-2,6-Dipp2 (Dipp = C6H3-2,6-Pri2): A Tin Analogue of an Alkyne. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:5930–5931. doi: 10.1021/ja0257164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pu L. Twamley B. Power P. P. Synthesis and Characterization of 2,6-Trip2H3C6PbPbC6H3-2,6-Trip2 (Trip = C6H2-2,4,6-i-Pr3): a Stable Heavier Group 14 Element Analogue of an Alkyne. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:3524–3525. doi: 10.1021/ja993346m. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bino A. Ardon M. Shirman E. Formation of a Carbon-Carbon Triple Bond by Coupling Reactions In Aqueous Solution. Science. 2005;308:234–235. doi: 10.1126/science.1109965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su P. Wu J. Gu J. Wu W. Shaik S. Hiberty P. C. Bonding Conundrums in the C2 Molecule: A Valence Bond Study. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2011;7:121–130. doi: 10.1021/ct100577v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ploshnik E. Danovich D. Hiberty P. C. Shaik S. The Nature of the Idealized Triple Bonds Between Principal Elements and the σ Origins of Trans-Bent Geometries—A Valence Bond Study. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2011;7:955–968. doi: 10.1021/ct100741b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidu I. Seth M. Ziegler T. Role Played by Isopropyl Substituents in Stabilizing the Putative Triple Bond in Ar'EEAr′ [E = Si, Ge, Sn; Ar' = C6H3-2,6-(C6H3-2,6-Pri2)2] and Ar*PbPbAr* [Ar* = C6H3-2,6-(C6H2-2,4,6-Pri3)2] Inorg. Chem. 2013;52:8378–8388. doi: 10.1021/ic401149h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danovich D. Bino A. Shaik S. Formation of Carbon–Carbon Triply Bonded Molecules from Two Free Carbyne Radicals via a Conical Intersection. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2013;4:58–64. doi: 10.1021/jz3016765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karni M. Apeloig Y. Schröder D. Zummack W. Rabezzana R. Schwarz H. HCSiF and HCSiCl: The First Detection of Molecules with Formal C≡Si Triple Bonds. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1999;38:331–335. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19990201)38:3<331::AID-ANIE331>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; , and related references therein.

- Danovich D. Ogliaro F. Karni M. Apeloig Y. Cooper D. L. Shaik S. Silynes (RC≡SiR') and Disilynes (RSi≡SiR'): Why Are Less Bonds Worth Energetically More? Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2001;40:4023–4026. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20011105)40:21<4023::AID-ANIE4023>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gau D. Kato T. Saffon-Merceron N. Cozar A. D. Cossio F. P. Baceiredo A. Synthesis and Structure of a Base-Stabilized C-Phosphino-Si-AminoSilyne. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010;49:6585–6588. doi: 10.1002/anie.201003616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lühmann N. Müller T. A Compound with a Si–C Triple Bond. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010;49:10042–10044. doi: 10.1002/anie.201005149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao H.-Y. Su M.-D. Chu S.-Y. A Stable Species with a Formal Ge≡C Triple Bond — A Theoretical Study. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2001;341:122–128. doi: 10.1016/S0009-2614(01)00461-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu P.-C. Su M.-D. Theoretical Designs for Germaacetylene (RC≡GeR’): A New Target For Synthesis. Dalton Trans. 2011;40:4253–4259. doi: 10.1039/C0DT00800A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu P.-C. Su M.-D. Effects of Substituents on the Thermodynamic and Kinetic Stabilities of HCGeX (X = H, CH3, F, and Cl) Isomers. A Theoretical Study. Inorg. Chem. 2011;50:6814–6822. doi: 10.1021/ic200930v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu P.-C. Su M.-D. A New Target for Synthesis of Triply Bonded Plumbacetylene (RC≡PbR): A Theoretical Design. Organometallics. 2011;30:3293–3301. doi: 10.1021/om2000234. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wen X.-T. Li Y.-C. Su M.-D. Substituent Effects on the Geometries and Energies of the Antimony-Silicon Multiple Bond. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 2014;87:816–818. doi: 10.1246/bcsj.20140041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Su M.-D., Doubly Bonded Molecules Containing Bismuth and Other Group 15 Elements in the Singlet and Triplet States, in Advances in Chemistry Research, ed. J. C. Taylor, Nova Science Publishers, Inc., New York, 2014, vol. 21, ch. 4, pp.149–184 [Google Scholar]

- Lu J.-S. Su S.-H. Yang M.-C. Wen X.-T. Xie J.-Z. Su M.-D. Substituent Effects on Boron-Bismuth Triple Bond: A New Target for Synthesis. Organometallics. 2016;35:3924–3931. doi: 10.1021/acs.organomet.6b00659. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J.-S. Yang M.-C. Su M.-D. The Effect of Substituents on the Stability of Triply Bonded Gallium≡Antimony Molecules: A New Target for Synthesis. Dalton Trans. 2017;46:1848–1856. doi: 10.1039/C6DT04522G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J.-S. Yang M.-C. Su M.-D. The Effect of Substituents on the Triply Bonded Boron≡Antimony Molecules: A Theoretical Approach. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017;19:8026–8033. doi: 10.1039/C7CP00421D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J.-S. Yang M.-C. Su M.-D. Substituent Effects on the Stability of Thallium and Phosphorus Triple Bonds: A Density Functional Study. Molecules. 2017;22:1111–1124. doi: 10.3390/molecules22071111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J.-S. Yang M.-C. Su M.-D. Triply-bonded Indium≡Phosphorus Molecules: Theoretical Designs and Characterization. RSC Adv. 2017;7:20597–20603. doi: 10.1039/C7RA01295K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J.-S., Yang M.-C., Su S.-H., Wen X.-T., Xie J.-Z. and Su M.-D.Triple Bonds between Bismuth and Group 13 Elements: Theoretical Designs and Characterization, in Recent Progress in Organometallic Chemistry, ed. M. M. Rahman and A. M. Asiri, InTechOpen, London, 1st edn, 2017, ch. 4, pp. 71–99 [Google Scholar]

- Lu J.-S. Yang M.-C. Su M.-D. Triply Bonded Gallium≡Phosphorus Molecules: Theoretical Designs and Characterization. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2017;121:6630–6637. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpca.7b04659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J.-S. Yang M.-C. Su M.-D. Aluminum−Phosphorus Triple Bonds: Do Substituents Make Al≡P Synthetically Accessible? Chem. Phys. Lett. 2017;686:60–67. doi: 10.1016/j.cplett.2017.08.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J.-S. Yang M.-C. Su M.-D. The Indium−Arsenic Molecules with an In≡As Triple Bond: A Theoretical Approach. ACS Omega. 2017;2:1172–1179. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.7b00113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J.-S. Yang M.-C. Su M.-D. Triple-Bonded Boron≡Phosphorus Molecule: Is That Possible? ACS Omega. 2018;3:76–85. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.7b01480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J.-S. Yang M.-C. Su M.-D. A Possible Target: the Triply Bonded Indium≡Antimony Molecules With High Stability. New J. Chem. 2018;42:6932–6941. doi: 10.1039/C8NJ00549D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J.-S., Yang M.-C., Su S.-H. and Su M.-D., The Effect of Substituent on Molecules that Contain a Triple Bond Between Arsenic and Group 13 Elements: Theoretical Designs and Characterizations, in Chemical Reactions in Inorganic Chemistry, ed. C. Saravanan, InTechOpen, London, 1st edn, 2018, ch. 4, pp. 51–73 [Google Scholar]

- Lu J.-S. Yang M.-C. Su M.-D. Is It Possible To Prepare and Stabilize the Triply Bonded Thallium≡Antimony Molecules Using Substituents? ACS Omega. 2018;3:10163–10171. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.8b00643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J.-S., Yang M.-C., Su S.-H. and Su M.-D., The Triply Bonded Al≡Sb Molecules: A Theoretical Prediction, in Basic Concepts Viewed from Frontier in Inorganic Coordination Chemistry, ed. T. Akitsu, InTechOpen, London, 1st edn, 2018, ch. 5, pp. 83–97 [Google Scholar]

- Paetzold P. Iminoboranes. Adv. Inorg. Chem. 1987;31:123–170. doi: 10.1016/S0898-8838(08)60223-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Paetzold P., Born Chemistry in Proceedings of the 6th International Meeting on Born Chemistry, Reactions at the Boron-Nitrogen Triple Bond, ed. S. Hermanek, World Scientific, Singapore, 1987, pp. 446–475 [Google Scholar]

- Paetzold P. New Perspectives in Boron Nitrogen Chemistry I. Pure Appl. Chem. 1991;63:345–350. [Google Scholar]

- Paetzold P. Boron-Nitrogen Analogues of Cyclobutadiene, Benzene and Cyclooctatetraene: Interconversions. Phosphorus, Sulfur Silicon Relat. Elem. 1994;93–94:39–50. doi: 10.1080/10426509408021797. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wright R. J. Phillips A. D. Allen T. L. Fink W. H. Power P. P. Synthesis and Characterization of the Monomeric Imides Ar‘MNAr‘ ‘ (M = Ga or In; Ar‘ or Ar‘ ‘ = Terphenyl Ligands) with Two-Coordinate Gallium and Indium. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:1694–1695. doi: 10.1021/ja029422u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright R. J. Brynda M. Fettinger J. C. Betzer A. R. Power P. P. Quasi-Isomeric Gallium Amides and Imides GaNR2 and RGaNR (R = Organic Group): Reactions of the Digallene, Ar′GaGaAr′ (Ar′ = C6H3-2,6-(C6H3-2,6-Pri2)2) with Unsaturated Nitrogen Compounds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:12498–12509. doi: 10.1021/ja063072k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiberg K. B. Application of the Pople-Santry-Segal CNDO Method to the Cyclopropylcarbinyl and Cyclobutyl Cation and to Bicyclobutane. Tetrahedron. 1968;24:1083–1096. doi: 10.1016/0040-4020(68)88057-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reed A. E. Curtiss L. A. Weinhold F. Intermolecular Interactions from a Natural Bond Orbital, Donor-Acceptor Viewpoint. Chem. Rev. 1998;88:899–926. doi: 10.1021/cr00088a005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood N. N. and Earnshaw A., Chemistry of the Elements, Pergamon, Oxford, England, 1984, pp. 452–513 [Google Scholar]

- Liptrot D. J. Power P. P. London Dispersion Forces in Sterically Crowded Inorganic and Organometallic Molecules. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2017;1:1–12. doi: 10.1038/s41570-016-0001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y. Truhlar D. G. Density Functionals with Broad Applicability in Chemistry. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008;41:157–166. doi: 10.1021/ar700111a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glendening E. D. Weinhold F. Natural resonance theory: I. general formalism. J. Comput. Chem. 1998;19:593–609. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-987X(19980430)19:6<593::AID-JCC3>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Glendening E. D. Weinhold F. Natural resonance theory: II. natural bond order and valency. J. Comput. Chem. 1998;19:610–627. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-987X(19980430)19:6<610::AID-JCC4>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glendening E. D. Badenhoop J. K. Weinhold F. Natural resonance theory: iii. Chemical Applications. J. Comput. Chem. 1998;19:628–646. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-987X(19980430)19:6<628::AID-JCC5>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.