Abstract

During the twentieth century, there was an explosion in understanding of the malaria parasites infecting humans and wild primates. This was built on three main data sources: from detailed descriptive morphology, from observational histories of induced infections in captive primates, syphilis patients, prison inmates and volunteers, and from clinical and epidemiological studies in the field. All three were wholly dependent on parasitological information from blood-film microscopy, and The Primate Malarias” by Coatney and colleagues (1971) provides an overview of this knowledge available at that time. Here, 50 years on, a perspective from the third decade of the twenty-first century is presented on two pairs of primate malaria parasite species. Included is a near-exhaustive summary of the recent and current geographical distribution for each of these four species, and of the underlying molecular and genomic evidence for each. The important role of host transitions in the radiation of Plasmodium spp. is discussed, as are any implications for the desired elimination of all malaria species in human populations. Two important questions are posed, requiring further work on these often ignored taxa. Is Plasmodium brasilianum, circulating among wild simian hosts in the Americas, a distinct species from Plasmodium malariae? Can new insights into the genomic differences between Plasmodium ovale curtisi and Plasmodium ovale wallikeri be linked to any important differences in parasite morphology, cell biology or clinical and epidemiological features?

Keywords: Plasmodium malariae, Plasmodium brasilianum; Plasmodium ovale curtisi; Plasmodium ovale wallikeri; Host transitions

Background

In The Primate Malarias (1971), by Coatney et al. [1], detailed species comparisons are presented based on descriptive morphology of both blood and mosquito stages, the geographic distribution of each parasite and certain features readily measurable in induced human infections, including the estimated duration of the liver-stage, time to symptoms and fever periodicity. Much of this work was performed in prison inmates in Georgia, USA. In this paper, fifty years since, the focus on the geographic, genomic and genetic characteristics of four primate malaria species—one currently regarded as zoonotic in South American monkeys, Plasmodium brasilianum, and three malaria parasites of Homo sapiens, namely Plasmodium malariae, Plasmodium ovale curtisi and Plasmodium ovale wallikeri. An exhaustive bibliography of reported identification of these species since 1890, across the globe and in different primate hosts, will also be presented.

Over the last two decades, the analytical techniques of evolutionary biology and the task of reconstructing phylogenetic relationships within the genus have benefited greatly from the explosion in genomic data available for malaria parasites, and the now well-established practise of non-invasive faecal sampling of parasite genomic material from the faeces of wild primates [2]. This wealth of data provides new understanding of diversity both within and among the primate-infecting Plasmodium species, and points to the importance of transitions into new primate hosts. These transitions are gateways to the radiation of parasite species, but also act as genetic bottlenecks, as evidenced by reduced diversity among parasites in the new host [2, 3].

Among the homophilic species considered of clinical importance, a range of life history and transmission strategies are evident, and each of these strategies have their equivalent counterparts among the parasites of living simian hosts, and those of Pan and Gorilla. Thus, the majority of evolution leading to these diverse life histories occurred in the parasite lineages of non-human primates in the evolutionary past. However, as with Plasmodium knowlesi, the zoonotic potential of P. brasilianum shows that host transition can be a dynamic process operating over an extended time period, rather than a singular event, and understanding this in the present is essential to maintain effective malaria elimination strategies world-wide.

Plasmodium brasilianum

History & discovery

The first report of P. brasilianum is based on a finding in the blood of a bald uakari (Cacajao calvus) imported from the Brazil Amazonas region to Hamburg, Germany in 1908 [4]. Initial studies reported that P. brasilianum closely resembles P. malariae, and to be a relatively common parasite of New World monkeys in Panama and Brazil (reviewed in [1]).

Distribution and known non-human primate hosts

Historically, natural infections of P. brasilianum were reported in various primates in Central and Southern America—Panama, Colombia, Venezuela, Peru, and Brazil. The spectrum of primate hosts (incl. sequence confirmed reports) is given in Table 1 [5–12], indicating that P. brasilianum has promiscuous host-specificity compared to other malaria parasites. Moreover, natural infections in humans have been reported from Venezuela [13].

Table 1.

Non-human primate host spectrum of Plasmodium brasilianum (modified after Coatney 1971)

| Host | Host Distribution | GenBank ID | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Black howler (Alouatta caraya) | Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Paraguay | [5] | |

| Brown howler (Alouatta guariba; Syn.: A. fusca) | Atlantic Forest—Brazil, Argentinia | [1] | |

| Northern brown howler (Alouatta guariba guariba) | Brazil | [5] | |

| Southern brown howler (Alouatta guariba clamitans) | Brazil, Argentinia | MF573323 | [6] |

| Mantled howler (Alouatta palliata) | Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Peru | KU999995 | [1] |

| Red howler (Alouatta seniculus) | Venezuela, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Brazil, French Guyana | AF138878 | [7] |

| Guatemalan black howler (Alouatta pigra; Syn.: Alouatta villosa) | Belize, Guatemala, Mexico | [1] | |

| Gray-handed night monkey (Aotus griseimembra) | Colombia, Venezuela | [8] | |

| Black-headed night monkey (Aotus nigriceps) | Brazil, Bolivia and Peru | KC906732 | [9] |

| White-bellied spider monkey (Ateles belzebuth) | Colombia, Ecuador, Venezuela, Peru, Brazil | [5] | |

| Peruvian spider monkey (Ateles chamek) | Peru, Brazil, Bolivia | KC906714 | [9] |

| Black-headed spider monkey (Ateles fusciceps) | Colombia, Ecuador, Panama | [1] | |

| Geoffroy's spider monkey (Ateles geoffroyi) | Central America incl. parts of Mexico, Colombia | [1] | |

| Nicaraguan spider monkey (Ateles geoffroyi geoffroyi) | Nicaragua, Costa Rica | [1] | |

| Hooded spider monkey (Ateles geoffroyi grisescens) | Panama, Colombia | [1] | |

| Brown spider monkey (Ateles hybridus) | Colombia, Venezuela | [8] | |

| Red-faced spider monkey (Ateles paniscus) | northern Brazil, Suriname, Guyana, French Guiana and Venezuela | [5] | |

| Southern muriqui (Brachyteles arachnoides) | Brazilian states Paraná, São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, Espírito Santo, Minas Gerais | [5] | |

| Bald uakari (Cacajao calvus) | Brazil, Peru | [5] | |

| Red bald-headed uakari (Cacajao calvus rubicundus) | Brazil | [5] | |

| Masked titi (Callicebus personatus) | Brazil | [5] | |

| White-headed marmoset (Callithrix geoffroyi) | Brazil | [10] | |

| Collared titi (Cheracebus torquatus; Syn.: Callicebus torquatus) | Brazil (Amazonas) | [5] | |

| White-fronted capuchin (Cebus albifrons) | Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, Peru, Trinidad and Tobago | [1] | |

| Colombian white-faced capuchin (Cebus capucinus) | Colombia, Ecuador | [1] | |

| Panamanian white-faced capuchin (Cebus imitator) | Honduras, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, Guatemala, Belize, Panama | [1] | |

| Varied white-fronted capuchin (Cebus versicolor) | Colombia | [8] | |

| White-nosed saki (Chiropotes albinasus) | Brazil, Bolivia | [5] | |

| Red-backed bearded saki (Chiropotes chiropotes) | North of the Amazon River and East of the Branco River, in Brazil, Venezuela and the Guianas | KC906730 | [9] |

| Black bearded saki (Chiropotes satanas) | Brazil | [5] | |

| Gray woolly monkey (Lagothrix cana) | Bolivia, Brazil, Peru | KC906726 | [9] |

| Brown woolly monkey (Lagothrix lagotricha) | Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Brazil | [5] | |

| Brown-mantled tamarin (Leontocebus fuscicollis, Syn.: Saguinus fuscicollis) | Bolivia, Brazil, Peru | [11] | |

| Golden-headed lion tamarin (Leontopithecus chrysomelas) | Brazil | [10] | |

| Golden lion tamarin (Leontopithecus rosalia) | Brazil | [10] | |

| Santarem marmoset (Mico humeralifer) | Brazil | [10] | |

| Gray's bald-faced saki (Pithecia irrorata) | Colombia, Bolivia, Peru, Brazil | KC906717 | [9] |

| Monk saki (Pithecia monachus) | Brazil, Peru, Ecuador Colombia | [5] | |

| White-faced saki (Pithecia pithecia) | Brazil, French Guiana, Guyana, Suriname, Venezuela | [5] | |

| Brown titi (Plecturocebus brunneus; Syn.: Callicebus brunneus) | Brazil, Peru, and Bolivia | [9] | |

| Chestnut-bellied titi (Plecturocebus caligatus, Syn.: Callicebus caligatus) | Brazil | JX045640 | [12] |

| Red-bellied titi (Plecturocebus moloch) | Brazil | KC906723 | [9] |

| Hershkovitz's titi (Plecturocebus dubius; Syn.: Callicebus dubius) | Bolivia, Brazil, Peru | JX045642 | [12] |

| Emperor tamarin (Saguinus imperator) | Bolivia, Brazil, Peru | KY709306 | [11] |

| Golden-handed tamarin (Saguinus midas) | Brazil, Guyana, French Guiana, Suriname | [5] | |

| Geoffroy's tamarin (Saguinus geoffroyi) | Panama, Colombia | [11] | |

| Martins's tamarin (Saguinus martinsi; both subspecies: Saguinus martinsi martinsi, Saguinus martinsi ochraceous) | Brazil | [10] | |

| Black tamarin (Saguinus niger) | Brazil | [11] | |

| Tufted capuchin (Sapajus apella) | Brazil, Venezuela, Guyanas, Colombia, Ecuador, Bolivia, Peru | KC906715 | [9] |

| Blond capuchin (Sapajus flavius) | Brazil | KX618476 | ** |

| Large-headed capuchin (Sapajus macrocephalus; Syn.: Sapajus apella macrocephalus) | Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru | [5] | |

| Robust tufted capuchin (Sapajus robustus) | Brazil | [5] | |

| Golden-bellied capuchin (Sapajus xanthosternos) | Brazil | [5] | |

| Black-capped squirrel monkey (Saimiri boliviensis) | Amazon basin in Bolivia, western Brazil, and eastern Peru | [5] | |

| Common squirrel monkey (Saimiri sciureus) | Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, French Guiana, Guyana, Peru, Suriname, Venezuela | JX045641 | [12] |

| Bare-eared squirrel monkey (Saimiri ustus) | Brazil, Bolivia | KC906728 | [9] |

**Unpublished: Bueno et al.

Genomic studies of Plasmodium brasilianum

Plasmodium brasilianum is a parasite thought to be closely related to P. malariae, and blood-stage infections of the two species present a morphologically identical picture, with discrimination determined by the host, monkey or human, respectively. The few molecular epidemiological studies reported so far have shown that P. brasilianum and P. malariae infections are almost indistinguishable genetically. Sequencing studies of the gene coding for the circumsporozoite protein (csp) appear not to differentiate the identity of the two parasites [14–16]. Similar, studies involving the merozoite surface protein-1 (msp1), the ssrRNA small subunit (18S) of ribosomes and the mitochondrial gene cytochrome b (cytb), have identified sequences that were 100% identical or that had only a few randomly distributed single nucleotide position differences [7, 13, 15–18]. Further, the close genetic resemblance of these parasites has been observed across studies in Brazil, Venezuela, Costa Rica, Peru, Colombia and French Guiana from infected humans, monkeys and mosquitoes [7–9, 11, 12, 15–18]. Under conditions of close contact, as shown in Yanomami people and monkeys species in the Venezuelan Amazon, both humans and non-human primates shared quartan parasites without any host specificity that are genetically identical in target candidate genes [13].

A small study using microsatellite genotyping showed that in 14 P. malariae isolates from infected individuals from the Brazilian Atlantic forest, all isolates had identical haplotypes, while in one mosquito sample from the same region a different haplotype was found [19]. In the same study, three P. brasilianum isolates from non-human primates sampled from a different region (Amazonia) were analysed, and diverse haplotypes were observed. Unfortunately, across all such studies to date only a small number of samples have been compared at only a few genetic loci. To understand the degree of similarity among P. brasilianum and P. malariae parasites, a comprehensive analysis of whole genome sequencing data is necessary, using many more parasites obtained from different hosts, across a range of geographic regions. Only one draft reference genome of P. brasilianum is available [20]. Similarly, only a few genomes are available for P. malariae, sourced from Africa and Asia, and none from South America [8, 20–22]. The apicoplast and mitochondrion genomes of P. brasilianum are indistinguishable from those of the P. malariae reference genome [20, 23], but further comparative analysis of nuclear genomes is needed to fully understand the status of these two species. This is made difficult by the scarcity of whole genome data, so it remains an open question whether these parasites are variants of a single species that is naturally adapted to both human and New World monkey hosts, and freely circulates between them. Related to this, it is also difficult to infer the direction of the cross-species transfer. Nevertheless, the similarity of these parasites suggests that monkeys can act as reservoirs of P. malariae / P. brasilianum, and this must be considered in control and eradication programmes.

Plasmodium malariae

History & discovery; epidemiology and disease

As Collins and Jeffery relate [24], P. malariae was named by Grassi and Feletti in 1890, following the observations of Golgi in 1886, who noted the existence of malaria parasites with either 48 h or 72 h cycles of fever, the latter subsequently being recognized as characteristic of P. malariae infections. This slow-growing species is widely distributed across the tropics and sub-tropics, with often asymptomatic infections characterized by low parasitaemia and a recognized ability to persist in a single host for years or decades [25, 26]. There is evidence that P. malariae can survive combination therapies used for treating acute P. falciparum malaria, and may present as a post-treatment recrudescence in P. falciparum patients [27–29]. Clinical malaria caused by P. malariae rarely progresses to severe, complicated or life-threatening illness, although the literature contains consistent reports of mortality due specifically to either glomerulonephritis or severe anaemia in small children with chronic infections [30].

Distribution and abundance

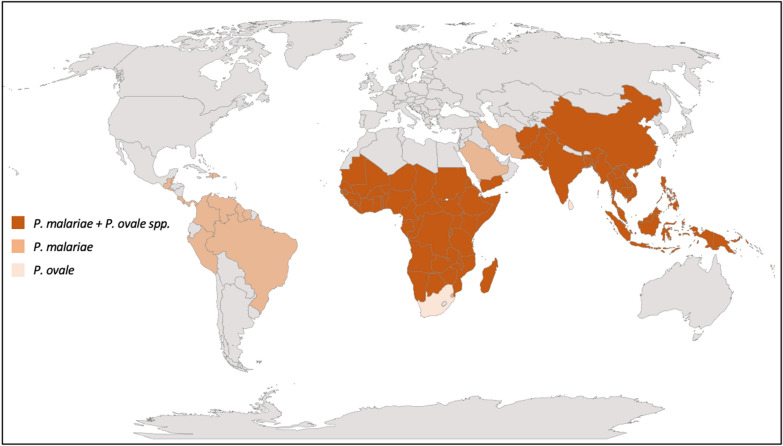

Plasmodium malariae is a cosmopolitan parasite distributed in sub-Saharan Africa, South-East Asia, western Pacific islands, and Central and South America [24]. Formerly this parasite was also present in the southern parts of the USA, Argentina, Bhutan, Brunei, South Korea, Morocco, Turkey, and parts of Europe where malaria was eradicated [31–33]. The distribution of this parasite is variable and patchy, and limited to particular mosquito vectors (sporogony needs a minimal temperature of 15 °C), yet autochthonous P. malariae cases have been documented from much of the tropics and sub-tropics (Fig. 1; Table 2) [34–143].

Fig. 1.

Reported global distributions of P. malariae and P. ovale spp.

Table 2.

Geographic distribution and prevalence of P. malariae

| Country | Region | Diagnostic Technique | Prevalence | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afghanistan | Jalalabad | PCR | 0.3% (1/306) | Mikhail et al. 2011 | [34] |

| Laghman District | Microscopy | 1 case | Ramachandra 1951 | [35] | |

| Chardhi | Microscopy | 1.4% (1/71 infants) | Ramachandra 1951 | [35] | |

| Angola | Bengo povince | PCR | 8.1% of malaria positives; 1.3% general | Fancony et al. 2012 | [36] |

| Luanda | PCR | 1.2% (1/81 symptomatic) | Pembele et al. 2015 | [37] | |

| Bangladesh | Bandarban | PCR | 2.7% (60/2246); 8% of 746 malaria positives; 4.3% of symptomatic patients | Fuehrer et al. 2014 | [38] |

| Belize | MoH official data | 0.04% of malaria positives (1990–2008) | Bardach et al. 2015 | [31] | |

| Benin | PCR | 8.3% (12/144) | Doderer-Lang et al. 2014 | [39] | |

| Botswana | Tutume | PCR | 0.6% (2/320 asymptomatic) | Motshoge et al. 2016 | [40] |

| Francistown | PCR | 0.5% (1/195 asymptomatic) | Motshoge et al. 2016 | [40] | |

| Kweneng East | PCR | 0.4% (3/687 asymptomatic) | Motshoge et al. 2016 | [40] | |

| Brazil | MoH official data | 0.08% (1990–2008) | Bardach et al. 2015 | [31] | |

| Apiacás—Mato Grosso State | PCR | 11.9% (59/497) | Scopel et al. 2004 | [41] | |

| Amazon Region | PCR | 33.3% (42/126 malaria positives) | Cunha et al. 2021 | [42] | |

| Espírito Santo | PCR | 2.3% (2/92) | de Alencar et al. 2018 | [43] | |

| Burkina Faso | PCR | 0.1% (1/695 pregnant) | Williams et al. 2016 | [44] | |

| Kossi District | PCR | 2.1–13.4% prevalence (decreasing from 2000–2011) | Geiger et al. 2013 | [45] | |

| Bassy and Zanga | PCR | 7.4% (8/108) of Pf positives | Culleton et al. 2008 | [46] | |

| Laye | Microscopy | 0.9–13.2% (children) | Gnémé et al. 2013 | [47] | |

| Burma/Myanmar | Kachin State | PCR | 0.1% (3/2598) | Li et al. 2016 | [48] |

| northern Myanmar | Microscopy | 0.04 (2/5585) | Wang et al. 2014 | [49] | |

| Burundi | Karuzi | Microscopy | 6.7% (228/3393) | Protopopoff et al. 2008 | [50] |

| Northern Imbo Plain | Microscopy | 5% (23/459 malaria positives) | Nimpaye et al. 2020 | [51] | |

| Cambodia | PCR | – | Khim et al. 2012 | [52] | |

| Ratanakiri | PCR | 2.1% (33/1792) | Durnez et al. 2018 | [53] | |

| 2007 Cambodian National Malaria Survey | PCR | 0.2% (17/7707) | Lek et al. 2016 | [54] | |

| Cameroon | PCR | – | Khim et al. 2012 | [52] | |

| Yaoundé region | PCR | – | Tahar et al. 1998 | [55] | |

| Adamawa region | PCR | 17.7% (of 1367) | Feufack-Donfack et al. 2021 | [56] | |

| Yaoundé region | PCR | 12% (of 122 asymptomatic children) | Roman et al. 2018 | [57] | |

| Central African Republic | Dzanga-Sangha Protected Area | PCR | 0.2% (2/95 asymptomatic) | Mapua et al. 2018 | [58] |

| Dzanga-Sangha region | PCR | 11.1% (of 540 symptomatic) | Bylicka-Szczepanowska et al. 2021 | [59] | |

| Chad | Microscopy | 1 case (infant; mixed with Pf)—imported case in the Netherlands | Terveer et al. 2016 | [60] | |

| China | Yunnan | PCR | 1% (1/103) | Li et al. 2016 | [48] |

| Colombia | Colombia’s Amazon department | PCR | 38.65% (of 1392 symptomatic) | Nino et al. 2016 | [61] |

| MoH official data | 0.03% (1990–2008) | Bardach et al. 2015 | [31] | ||

| Colombian Amazon trapezium | PCR | 43.2% (862/1995 symptomatic) | Camargo et al. 2018 | [62] | |

| Comores | Grande Comore | PCR | 0.62% (1/159) | Papa Mze et al. 2016 | [63] |

| Congo DRC | Kinshasa province | PCR | 39% asymptomatic and 7% symptomatic (of malaria positives) | Nundu et al. 2021 | [64] |

| PCR | 3.7% (mixed with Pf of malaria positives) | Kiyonga Aimeé et al. 2020 | [65] | ||

| PCR | 1.5% (1/65; mixed with Pf; asymptomatic children) | Podgorski et al. 2020 | [66] | ||

| PCR | 4.9% (7/142; 6 mixed with Pf; symptomatic) | Kavunga-Membo et al. 2018 | [67] | ||

| Congo Republic | PCR | 0.9% (8 of 851) | Culleton et al. 2008 | [46] | |

| Costa Rica | PCR | 4 cases | Calvo et al. 2015 | [68] | |

| Cote d'Ivoire | PCR | Khim et al. 2012 | [52] | ||

| Yamoussoukro | PCR | 1.6% (7/438) febrile; 2.3% (8/346) afebrile | Ehounoud et al. 2021 | [69] | |

| Dominican Republic | MoH official data | 0.02% (1990–2008) | Bardach et al. 2015 | [31] | |

| El Salvador | MoH official data | 0.01% of malaria positives (1990–2008); free of malaria since 2021 | Bardach et al. 2015 | [31] | |

| Equatorial Guinea | Bioko Island (Ureka, Bareso, Sacriba) | PCR | 10–31% (asymptomatic < 10 years) | Guerra-Neira et al. 2006 | [70] |

| Bioko Island | PCR | 15.3% (9/59; blood donors) | Schindler et al. 2019 | [71] | |

| Eritrea | Eritrean migrants | 0.7% (of 146) | Schlagenhauf et al. 2018 | [72] | |

| Ethiopia | Southern Ethiopia Omo Nada | PCR | 2 mono and 2 mixed with Pf | Mekonnen et al. 2014 | [73] |

| Amhara Regional State | PCR | 0.3% (1/359) | Getnet et al. 2015 | [74] | |

| French Guyana | MoH official data | 1.39% of malaria positives (1990–2008) | Bardach et al. 2015 | [31] | |

| PCR | Case (GenBank: AF138881) | Fandeur et al. 2000 | [7] | ||

| Gabon | Franceville | PCR | 2.5% (4/162); febrile children | Maghendji-Nzondo et al. 2016 | [75] |

| Lambarene | PCR | 0.5% (1/206) | Culleton et al. 2008 | [46] | |

| Fougamou and villages in the surroundings | PCR | 23% (193/834) | Woldearegai et al. 2019 | [76] | |

| Gambia | Microscopy | rarely |

http://www.rollbackmalaria.org/files/files/countries/Gambia.pdf (accessed: July 25th, 2017) |

||

| Ghana | Kwahu-South | PCR | 12.7% (18/142) | Owusu et al. 2017 | [77] |

| PCR | 12.8% (45/352) coinfections with Pf | Culleton et al. 2008 | [46] | ||

| Ahafo Ano South District of the Ashanti region | PCR | 28% (76/274) school children | Dinko et al. 2013 | [27] | |

| Guatemala | MoH official data | 0.01% of malaria positives (1990–2008) | Bardach et al. 2015 | [31] | |

| Guinea | PCR | Khim et al. 2012 | [52] | ||

| Microscopy | 0.3% (2/724) in young infants, 12.0% (90/748) in children 1–9 years of age, and 5.8% (43/743) in children 10–15y. 97% (131/135) mixed with Pf | Ceesay et al. 2015 | [78] | ||

| Guinea-Bissau | PCR | Tanomsing et al. 2007 | [79] | ||

| Antula | PCR | 18% (of 60) in 1995; 4% (of 71) in 1996 | Arez et al. 2003 | [80] | |

| Guyana | Georgetown | PCR | 3 PCR confirmed cases | Baird et al. 2002 | [81] |

| MoH official data | 0.03% of malaria positives (1990–2008) | Bardach et al. 2015 | [31] | ||

| Haiti | PCR | Imported to Jamaica | Lindo et al. 2007 | [82] | |

| India | PCR | GenBank ID: KU510228 | Krishna et al. unpublished | ||

| various | rare | Reviewed in Chatuverdi et al. 2020 | [83] | ||

| Odisha | PCR | 9.1% (10/110) mono; 10.9% (12/110) mixed; febrile malaria positives | Pati et al. 2017 | [84] | |

| Indonesia | Papua | PCR | Tanomsing et al. 2007 | [79] | |

| Flores—Ende District | PCR | 1.9% (of 1509) | Kaisar et al. 2013 | [85] | |

| North Sumatra | PCR | 3.4% of 3731 participants; 2.9–11.5% of malaria positives | Lubis et al. 2017 | [29] | |

| Iran | Baluchestan | PCR | 1.4% (2/140) | Adel and Ashgar 2008 | [86] |

| Kenya | Lake Victoria basin Western Kenya | PCR | 5.3% (35/663) of asymptomatic infections and 3.3% (8/245) of clinical cases | Lo et al. 2017 | [87] |

| Kisii district | PCR | 11.6% (84 of 722) | Culleton et al. 2008 | [46] | |

| Laos | PCR | Tanomsing et al. 2007 | [79] | ||

| northern provinces | PCR | 0.05% (3/5082); 7.7% of PCR positives for malaria; 2 mono + 1 mixed Pv | Lover et al. 2018 | [88] | |

| Liberia | Far | microscopy | 39% | Björkman et al. 1985 | [89] |

| PCR | 3 cases imported to China | Cao et al. 2016 | [90] | ||

| Madagascar | PCR | Khim et al. 2012 | [54] | ||

| Ampasimpotsy | PCR | 2.1% (12/559 malaria positives) | Mehlotra et al. 2019 | [91] | |

| Malawi | PCR | 1 case imported to China | Cao et al. 2016 | [90] | |

| Dedza and Mangochi | PCR | 9.4% of 2918 | Bruce et al. 2011 | [92] | |

| Malaysia | Malaysian Borneo | PCR | 2.8% (1/47) | Lee et al. 2009 | [93] |

| Sabah | PCR | 0.6% (8/1366); 7 mono + 1 mixed with Pf | William et al. 2014 | [94] | |

| Peninsular Malaysia | PCR | 18% (20/111) of malaria positives; 16 mono; 1 with Pf and 3 with Pk | Vythilingam et al. 2008 | [95] | |

| Mali | PCR | Khim et al. 2012 | [52] | ||

| PCR | 14/603; 3 mono, 10 Pf mix, 1 Pf, PoC mix; pregnant | Williams et al. 2016 | [44] | ||

| Northern Mali | PCR | 9.4–22.5% of malaria positives—asymptomatic | Koita et al. 2005 | [96] | |

| Mauritania | Boghe-Sahelian zone | Microscopy | 0.03% (1/3445 children); 0.7% (1/143 malaria positives) | Ouldabdallahi Moukah et al. 2016 | [97] |

| Hodh Elgharbi (Sahelian zone) | Microscopy | 1.1% (4/378) of malaria positives febrile patients; 0.3% (4/1161) in febrile patiens | Ould Ahmedou Salem et al. 2016 | [98] | |

| Mayotte | Mayotte Island | Microscopy | 4% of all malaria positive cases | Maillard et al. 2015 | [99] |

| Mozambique | Manchiana and Ilha Josina | PCR | Manchiana: 19.3% (27/140); Ilha Josina: 28.7% (54/188) | Marques et al. 2005 | [100] |

| Namibia | Bushmanland | Microscopy | rare | mentioned in Noor et al. 2013 | [101] |

| Niger | south-eastern | Microscopy | 1.7% of malaria positves | Doudou et al. 2012 | [102] |

| Nigeria | Ibadan area | PCR | 11.7% (69/590), children; mainly mixed infections | May et al. 1999 | [103] |

| Eboyi State | PCR | 6.67% mono; 2% mixed with pf of 150 HIV positive patients | Nnoso et al. 2015 | [104] | |

| Lafia | PCR | 0.7% (7/960)—3 mono and 4 mixed Pf, asymptomatic children | Oyedeji et al. 2017 | [105] | |

| Ibadan | PCR | 66% (352/530) of malaria positive asymptomatic adolescents (ages 10–19 years), mainly mixed | Abdulraheem et al. 2021 | [106] | |

| Pakistan | PCR | 1 case imported to China | Cao et al. 2016 | [90] | |

| Microscopy | 0.4% (2/521) hospitalized patients | Beg et al. 2008 | [107] | ||

| Panama | MoH official data | 0.01% of malaria positives (1990–2008) | Bardach et al. 2015 | [31] | |

| Eradicated?—Last case in 1972 | Hurtado et al. 2020 | [108] | |||

| Papua New Guinea | East Sepik Province | PCR | 4.62% (100/2162); 75 mono and 25 mixed | Mehlotra et al. 2000 | [109] |

| PCR | Oro (0.7%); Eastern Highlands (0.2%); Madang (1.5%); New Ireland (1.3%); East New Britain (0.3%); Bougainville (0.1%) | Hetzel et al. 2015 | [110] | ||

| Peru | south-east Amerindian population | microscopy | above 80% of all malaria infections | Sulzer et al. 1975 | [111] |

| MoH official data | 0.02% of malaria positives (1990–2008) | Bardach et al. 2015 | [31] | ||

| Philippines | Palawan | Microscopy | 0–0.5% | Oberst et al. 1988 | [112] |

| Mindanao | PCR | 0.03% (1/2639) asymptomatic | Dacuma et al. 2021 | [113] | |

| Rwanda | Rukara Health Centre | PCR | 1% (1/99) | Culleton et al. 2008 | [46] |

| Sao Tome/Principe | Principe | Microscopy | 11 cases | Lee et al. 2010 | [114] |

| Saudi Arabia | Western regions | Microscopy | 0.5% (48/8925 malaria positives) | Amer et al. 2020 | [115] |

| Senegal | Kedougou | PCR | GenBank ID: KX417705 | unpublished | |

| southeastern Senegal | PCR | 3.3% of 122 asymptomatic participants | Badiane et al. 2021 | [116] | |

| Sierra-Leone | Moyamba District | Microscopy | 2.1% Pm mono | Gbakima et al. 1994 | [117] |

| Bo | PCR | 0.4% (2/534) febrile patients | Leski et al. 2020 | [118] | |

| Somalia | microscopy | 5% of all malaria positives | reviewed in Oldfield et al. 1993 | [119] | |

| Imported to USA—marines | microscopy | 0.9% (1/106) | Newton et al. 1994 | [120] | |

| South Sudan | Jonglei State | microscopy | 6 of 392; 7.7% of malaria positives | Omer et al. 1978 | [121] |

| Sudan | Gezira | microscopy | 38 of 1987; 4.1% of malaria positives | Omer et al. 1978 | [121] |

| East Sudan | PCR | case report | Imirzalioglu et al. 2006 | [122] | |

| Red Sea State | microscopy | 1.1% (3/283 malaria positives) | Ageep 2013 | [123] | |

| Suriname | MoH official data | 5.25% of malaria positives (1990–2008) | Bardach et al. 2015 | [31] | |

| microscopy | 12% of 86 Pf positives | Peek et al. 2004 | [124] | ||

| Swaziland | PCR | 0.02% (1/4028) | Hsiang et al.2012 | [125] | |

| Tanzania | Zanzibar | PCR | 24—14 mono and 10 mixed Pf | Xu et al. 2015 | [126] |

| Zanzibar | PCR | 0.5% (3/594) febrile patients but Pf-RDT negative | Baltzell et al. 2013 | [127] | |

| Kibiti District | PCR | 2.4% in 2016 (11.3–16.2% in the 1990’s) | Yman et al. 2019 | [128] | |

| Thailand | PCR | Various GenBank entries (e.g. EF206337) | Tanomsing et al. 2007 | [79] | |

| Kanchanaburi Province | PCR | 0.2% (2/812) | Yorsaeng et al. 2019 | [129] | |

| MoH |

2012: 0.3% (48/16196 malaria positives) 2013: 0.5% (80/14740 malaria positives) 2015: 0.2% (26/12637 malaria positives) 2016: 0.2% (26/15451 malaria positives) |

Summarized in Yorsaeng et al. 2019 | [129] | ||

| Timor-Leste | Microscopy | 0.57% (6 cases) | Bragonier et al. 2002 | [130] | |

| Imported to Australia | 0.6% (3/501 malaria positives from East Timor; 1 mono and 2 mixed) | Elmes 2010 | [131] | ||

| Togo | PCR | Khim et al. 2012 | [52] | ||

| microscopy | Dorkenoo et al. 2016 | [132] | |||

| Uganda | PCR | GenBank ID:AB354570 | Hayakawa et al. 2008 | [133] | |

| PCR | 4.8% (48/1000) blood donors; 31.2% of all malaria positives | Murphy et al. 2020 | [134] | ||

| Vanuatu | Mentioned in Maguire et al. 2006 | [135] | |||

| Venezuela | PCR | Various; e.g. KM016331 | Lalremruata et al. 2015 | [13] | |

| Yanomami villages | PCR | 11.8% (75/630); 25 mixed infections | Lalremruata et al. 2015 | [13] | |

| MoH official data | 0.09% of malaria positives (1990–2008) | Bardach et al. 2015 | [31] | ||

| Vietnam | PCR | Various GenBank entries (e.g. EF206329) | Tanomsing et al. 2007 | [79] | |

| Khanh Hoa Province | PCR | 4.8% (6/125) malaria positives | Maeno et al. 2017 | [136] | |

| Ninh Thuan Province | PCR | 30.4% (204/671) of malaria positives; 95 mono and 109 mixed infections | Nguyen et al. 2012 | [137] | |

| Yemen | Taiz-region | Microscopy | 0.06% (1/1638) asymptomatic | Al-Eryani et al. 2016 | [138] |

| highlands | Microscopy | 0.2% (1/455) symptomatic; 1.3% (1/78) Plasmodium positives | Al-Mekhlafi et al. 2011 | [139] | |

| Zambia | Nchelenge District | Microscopy | 0.6% (5/782) Children < 10 years; 2.1%, (5/236) of malaria positives | Nambozi et al. 2014 | [140] |

| Western and Southern Province | PCR | 1.7% (5/304); 2 mono and 3 mixed Pf | Sitali et al. 2019 | [141] | |

| Choma District, Southern Province | PCR | 0.2% of 3292 participants; 2 Pm and 5 Pm + Pf; low transmission area | Laban et al. 2015 | [142] | |

| Zimbabwe | Microscopy | 1.8% of 51,962; 8.3% of malaria infections (1972–1981) | Taylor and Mutambu 1986 | [143] |

Assessment of the abundance of P. malariae is difficult because this parasite has been neglected by researchers, and studies differ (e.g. symptomatic patients vs. population studies; Table 2). Some epidemiological studies reported a high prevalence (15–30%) in Africa, Papua New Guinea, and the Western Pacific, in contrast to scanty observations (1–2%) from Asia, the Middle East, Central and Southern America [144]. However, with the advent of molecular diagnostic techniques this parasite species has been reported more frequently, being found in regions where it was not previously thought be present (e.g. Bangladesh), more commonly observed in mixed infections with P. falciparum [24], and identified as recrudescent infections in historical cases from areas such as Greece, formerly endemic for malariae malaria, but since having eliminated contemporary transmission of the disease [145].

Genomic studies of Plasmodium malariae

Large-scale genomic studies of the neglected malaria parasites and zoonotic species have been difficult to date, limited by infections having low parasite densities and being mixed with other Plasmodium species, thereby making it difficult to obtain sufficient parasite DNA to perform whole genome sequencing. For P. malariae, the first partial genome using next-generation sequencing was produced from CDC Uganda I strain DNA [22, 146]. A subsequent study generated a more complete reference using long-read sequencing technology from DNA of the P. malariae isolate PmUG01, from an Australian traveller infected in Uganda [22, 23]. Additional genomic data from short-read Illumina data of travellers’ isolates from Mali, Indonesia and Guinea, and one patient in Sabah, Malaysia, were also reported by Rutledge et al. Analysis of these genomes revealed that around 40% of the 33.6 Mbp genome (24% GC content), particularly in subtelomeric chromosome regions, is taken up by multigene families, as seen in P. ovale species [22, 25]. The P. malariae genome displays some unique characteristics, such as the presence of two large families, the fam-l and fam-m genes, with almost 700 members [22, 23]. Most of these genes encode proteins with a PEXEL export signal peptide and many encode proteins with structural homology to Rh5 of P. falciparum, the only known protein that is essential for P. falciparum red blood cell invasion [147]. These observations suggest that the fam-l and fam-m gene products may also have an important role in binding to host ligands. Other gene families, such as the Plasmodium interspersed repeat (pir) loci that are present in many species in the genus, including in Plasmodium vivax (~ 1500 vir genes), are present in the P. malariae genome. Of the 250 mir genes identified, half are possible pseudogenes. Products of the pir genes are predicted to be exported to the infected erythrocyte surface and may have a role in cell adhesion. Like pir genes, SURFIN proteins are also encoded in the P. malariae genome at around 125 loci, much greater than the number present in P. falciparum (ten) or P. vivax (two). Another unique feature of the P. malariae genome is the presence of 20 copies, in a single tandem array, of the P27/25 gene, a sexual-stage cytoplasmic protein with a possible role in maintaining cell integrity. P27/25 is encoded by a single copy gene in all other species evaluated to date [23, 25].

The sequences of an additional eighteen P. malariae genomes from Africa and Asia have recently been reported [21]. These were derived directly from patient isolates, using a selective whole genome DNA amplification (SWGA) approach to increase the relative abundance of parasite DNA sequence reads relative to host reads. A total of 868,476 genome-wide SNPs were identified, filtered to 104,583 SNPs after exclusion of the hypervariable subtelomeric regions. Phylogenetic analysis showed a clear separation of isolates sourced from Africa and Asia, similar to observations from the analysis of sequence data from the circumsporozoite (pmcsp) gene [148]. Many non-synonymous SNPs in orthologs of P. falciparum drug resistance-associated loci (pmdhfr, pmdhps and pmmdr1) were detected [21, 52], but their impact on drug efficacy remains unknown. Thus, to date, there are no validated molecular markers of drug resistance in P. malariae parasites although, as noted above, prophylaxis breakthrough, treatment failures and emergence following treatment for other species have been reported [26–29, 149].

In the wider Plasmodium species context, phylogenetic analysis has shown that P. malariae isolates group with malariae-like species that infect monkeys and non-human primates [2, 23]. Plasmodium malariae parasites also cluster closer to P. ovale spp., but in separate clades, and more generally in a clade with P. vivax, P. knowlesi and Plasmodium cynomolgi that is distant from the Laverania sub-genus exemplified by P. falciparum and Plasmodium reichenowi [2, 150]. Given the range of primate hosts that are infected by P. malariae, P. brasilianum and their close relatives, further genomic studies are needed to tease out the two main questions raised by the studies so far:

-

o

Should P. brasilianum, as is currently circulating in South America, and P. malariae be considered distinct, non-recombining species?

-

o

What is the extent of the radiation of P. malariae-like species in the great apes?

Plasmodium ovale curtisi and Plasmodium ovale wallikeri

History & discovery

First identified in Liverpool by Stephens in 1918, the index case of ovale malaria was a British army private, returning to the UK in 1918 following deployment in “East Africa”, and having reported an episode of symptomatic malaria in December, 1916 [151]. This soldier’s blood films were examined over several months, with no mention of any treatment being offered, during which time the presence of fimbriated, oval infected red cells was noted as a key feature, together with a 48 h fever periodicity. This “new parasite of man” (sic) was thus characterized as a benign tertian infection and named Plasmodium ovale in the primary paper, published in 1922. Some additional detailed description of the parasite and its presentation was published by Stephens and Owen in 1927 [152].

For much of the twentieth century, ovale malaria remained a minor entrant in parasitology textbooks, including Coatney et al. [1], until the advent of molecular diagnostic studies in the 1990s began to uncover evidence of genetic dimorphism [153], leading to a series of papers in the first decade of the twenty-first century examining the impact of this dimorphism on molecular and antigen-based diagnosis [154–158]. A multi-centre effort to gather 51 geographically diverse parasite isolates and generate sequencing data across seven genetic loci was then able to demonstrate that ovale malaria was the result of infection by either of two non-recombining, sympatric sibling parasite species, which were named P. ovale curtisi and P. ovale wallikeri [159]. In the decade that followed, various molecular tools were developed to distinguish the two ovale species, and there was an explosion of our understanding of the contribution of the newly recognized parasites to malaria burden across the tropics.

Distribution and abundance

Although the original identification of P. ovale sensu lato (s.l.) by Stephens was in a British soldier who contracted malaria in “East Africa”, the species was subsequently recognized as highly endemic in West Africa (especially Nigeria). Coatney et al. described the distribution of the species as extending to the East African Coast, and as far south as Mozambique [1]. Outside Africa, ovale malaria was sporadically reported from Papua New Guinea, Indonesian islands and some South-East Asian countries [144]. However, with the introduction of molecular diagnostic tools and recognition and widespread acceptance of the two sympatric species, P. o. curtisi (former “classic” type) and P. o. wallikeri (former “variant” type) [159], a much more complex understanding of these parasites has developed. Molecular diagnostics have greatly facilitated the confirmation of the presence of ovale malaria parasites in much of Africa and Asia, including countries where it was not previously known to be present (e.g. Bangladesh, Afghanistan, Angola) [35–37, 160–162], and in non-human primates [163]. However, it remains generally accepted that these parasites are not endemic in the Americas [159].

Infections with ovale malaria parasites are often asymptomatic and parasite densities low, leading to difficulties in accurate microscopic diagnosis and some uncertainties as to distribution in the recent past. Given the presence of intra-erythrocytic stippling on thin films, and the irregular shapes adopted by ovale-infected cells, there is some morphological similarity to P. vivax, which exacerbates diagnostic difficulties. This also influenced early phylogenetic thinking; Coatney and colleagues write that “from the vivax-like stem developed a morphologically similar species, P. ovale, that was capable of surviving in (African) hominids …” (1). Moreover, mixed infections with other human malaria parasites are very common. Double infections of P. ovale curtisi and P. ovale wallikeri in the same individual have also been reported (e.g. Angola, Bangladesh) [36, 161], confirming the lack of recombination between the two species. However, reported prevalence estimates vary widely among various studies, reflecting different study designs and blood sample collection strategies (e.g. asymptomatic vs. febrile patients). The known distribution of P. ovale spp., P. o. wallikeri and P. o. curtisi is presented in Fig. 2, and a detailed listing of reports identifying these species, including GenBank accession ID where relevant, is given in Table 3 [27, 36, 48, 58, 72, 76, 83, 90, 97, 102, 106, 116, 118, 137, 156, 159, 166–217].

Fig. 2.

Reported global distributions of P. ovale curtisi and P. ovale wallikeri. Poc Plasmodium ovale curtisi, Pow Plasmodium ovale wallikeri

Table 3.

Geographic distribution and prevalence of P. ovale sp., P. ovale wallikeri and P. ovale curtisi (Sequences submitted to GenBank as P. ovale were assigned to species level post hoc)

| Country | Type | Diagnostic Technique | Prevalence | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afghanistan | P. ovale curtisi | PCR | Imported to Switzerland | Nguyen et al. 2020 | [162] |

| Angola | P. ovale curtisi | Sequence | GenBank: FJ409571; FJ409567 | Duval et al. 2009 | [163] |

| P. ovale wallikeri | Sequence | GenBank: MG588149; imported to China | Zhou et al. Unpublished | – | |

| P. ovale wallikeri | PCR | 0.3% (11/3316) 3 mono + 8 mixed; 2% (11/541) malaria positives | Fançony et al. 2013 | [36] | |

| P. ovale curtisi | PCR | 0.3% (11/3316) 4 mono + 7 mixed; 2% (11/541) malaria positives | Fançony et al. 2013 | [36] | |

| Bangladesh | P. ovale curtisi | Sequence | 0.26% (1/379) symptomatic; 0.45% (10/1867) incl. asymptomatic participants; Mono—36.4% | Fuehrer et al. 2012 | [161] |

| P. ovale wallikeri | Sequence | 0.79% (3/379) symptomatic; 0.53% (12/1867) incl. asymptomatic participants; Mono—46.1% | Fuehrer et al. 2012 | [161] | |

| Benin | P. ovale wallikeri | Sequence | GenBank: GQ183063; EU266604 | Sutherland et al. 2010 | [159] |

| P. ovale wallikeri | PCR | 1 isolate in meta-analysis | Bauffe et al. 2012 | [164] | |

| P. ovale curtisi | PCR | 2 isolates in meta-analysis | Bauffe et al. 2012 | [164] | |

| Botswana | P. ovale curtisi | PCR | 1.85% (30/1614); 11 mono and 19 mixed | Motshoge et al. 2021 | [165] |

| Brunei | P. ovale sp. | 1 case imported to China | Cao et al. 2016 | [90] | |

| Burkina Faso | P. ovale curtisi | PCR | 3 isolates | Calderaro et al. 2012 | [166] |

| P. ovale wallikeri | PCR | Imported to Germany | Frickmann et al. 2019 | [167] | |

| Burma/Myanmar | P. ovale curtisi | Sequence | Various: e.g. KX672039; AB182496 | Win et al. 2004; Li et al. 2016 | [48, 156] |

| P. ovale wallikeri | Sequence | Various: e.g. AB182497 | Win et al. 2004 | [48] | |

| Burundi | P. ovale wallikeri | PCR | 1 isolate, imported to UK | Nolder et al. 2013 | [168] |

| Cambodia | P. ovale curtisi | Sequence | GenBank: e.g. FJ409571 | Duval et al. 2009 | [163] |

| P. ovale wallikeri | Sequence | Incardona et al. 2005 | [169] | ||

| Cameroon | P. ovale curtisi | Sequence | Imported to Singapore; GenBank: e.g. KP050401 | Chavatte et al. 2015 | [170] |

| P. ovale curtisi | Sequence | Kojom Foko et al. 2021 | [171] | ||

| P. ovale wallikeri | Sequence | GenBank: e.g. FJ409566 | Duval et al. 2009 | [56] | |

| Central African Republic | P. ovale curtisi | Sequence | Various GenBank: e.g. FJ409571; KP050465 | Duval et al. 2009; Chavatte et al. 2015 | [163, 170] |

| P. ovale wallikeri | Sequence | 1.1% (1/95) asymptomatics; 4.3% (1/23) of malaria positives; GenBank: MG241227 | Mapua et al. 2018 | [58] | |

| Chad | P. ovale curtisi | PCR | 1 isolate in meta-analysis | Bauffe et al. 2012 | [164] |

| P. ovale wallikeri | PCR | 1 isolate in meta-analysis | Bauffe et al. 2012 | [164] | |

| P. ovale curtisi | PCR | Imported to China | Zhou et al. 2019 | [172] | |

| P. ovale wallikeri | PCR | Imported to China | Zhou et al. 2019 | [172] | |

| China (Yunnan) | P. ovale curtisi | Sequence | GenBank: KX672045; certified malaria free since 2021 | Li et al. 2016 | [48] |

| Comoros | P. ovale curtisi | PCR | 7 isolates | Bauffe et al. 2012 | [164] |

| P. ovale wallikeri | PCR | 11 isolates | Bauffe et al. 2012 | [164] | |

| Congo DRC | P. ovale curtisi | Sequence | GenBank: e.g. FJ409567 | Duval et al. 2009 | [163] |

| P. ovale wallikeri | Sequence | 1% (2/198) children < 5 years; GenBank: KT867772 | Gabrielli et al. 2016 | [173] | |

| Congo Republic of the | P. ovale curtisi | Sequence | Imported to China; GenBank: MT430962 | Chen et al. 2020 | [174] |

| P. ovale curtisi | PCR | 4 clinical cases | Oguike et al. 2011 | [175] | |

| P. ovale wallikeri | PCR | 2 clinical cases | Oguike et al. 2011 | [175] | |

| Cote d’Ivoire | P. ovale curtisi | Sequence | GenBank: e.g. FJ409567; KP050411 | Duval et al. 2009; Chavatte et al. 2015 | [163, 170] |

| P. ovale wallikeri | Sequence | GenBank: e.g. GU723538 | Sutherland et al. 2010 | [159] | |

| Djibouti | P. ovale sp. | Rarely, 1 case in 2018/19 season | de Santi et al. 2021 | [176] | |

| East Timor (Timor-Leste) | P. ovale sp. |

Present according to WHO; Documented in West Timor |

Gundelfinger 1975 | [177] | |

| Equatorial Guinea | P. ovale curtisi | Sequence | GenBank: JF505386 | Unpublished | – |

| P. ovale wallikeri | Sequence | GenBank: e.g.: KP050469 | Chavatte et al. 2015 | [170] | |

| P. ovale curtisi | PCR | Bioko Island—0.9–1.4% ovale in total population | Oguike et al. 2011 | [175] | |

| P. ovale wallikeri | PCR | Bioko Island—0.9–1.4% ovale in total population | Oguike et al. 2011 | [175] | |

| Eritrea | P. ovale sp. | 1 case—imported to Germany | Roggelin et al. 2016 | [178] | |

| P. ovale sp. | 2.7% (4/146)—imported to Europe | Schlagenhauf et al. 2018 | [72] | ||

| Ethiopia | P. ovale curtisi | Sequence | 0.7% (2/300) of symptomatic patients; 1.1% (2/184) of malaria positives, GenBank: e.g. KF536874 | Alemu et al. 2013 | [179] |

| P. ovale wallikeri | Sequence | 2.3% (7/300) of symptomatic patients; 3.8% (7/184) of malaria positives, GenBank: e.g. KF536876 | Alemu et al. 2013 | [179] | |

| Gabon | P. ovale curtisi | Sequence | GenBank: e.g.: FJ409571; MG869603 | Duval et al. 2009; Groger et al. 2019 | [163, 180] |

| P. ovale wallikeri | Sequence | GenBank: e.g.: KJ170104; MG869598 | Groger et al. 2019 | [180] | |

| P. ovale curtisi | PCR | Rural Gabon—8.9% of malaria positives; 7 of 74 mono infection | Woldearegai et al. 2019 | [76] | |

| P. ovale wallikeri | PCR | Rural Gabon—4.6% of malaria positives; 1 of 38 mono infection | Woldearegai et al. 2019 | [76] | |

| Gambia, The | P. ovale wallikeri | PCR | 0.16% (1/604) pregnant | Williams et al. 2016 | [44] |

| Ghana | P. ovale curtisi | Sequence | GenBank: e.g.: GU723554 | Sutherland et al. 2010 | [159] |

| P. ovale wallikeri | Sequence | GenBank: e.g.: KP725067 | Oguike and Sutherland 2015 | [181] | |

| P. ovale curtisi | PCR | Ashanti Region, 4% (15/284) malaria positives | Heinemann et al. 2020 | [182] | |

| P. ovale wallikeri | PCR | Ashanti Region, 3% (12/284) malaria positives | Heinemann et al. 2020 | [182] | |

| P. ovale curtisi | PCR | 27 cases—Children 5–17 | Dinko et al. 2013 | [27] | |

| P. ovale wallikeri | PCR | 7 cases—Children 5–17 | Dinko et al. 2013 | [27] | |

| Guinea | P. ovale curtisi | Sequence | GenBank: e.g.: FJ409571 | Duval et al. 2009 | [181] |

| P. ovale curtisi | PCR | Imported to France | Joste et al. 2021 | [183] | |

| P. ovale wallikeri | PCR | Imported to China and France | Zhou et al. 2018; Joste et al. 2021 | [183, 184] | |

| Guinea-Bissau | P. ovale curtisi | Sequence | GenBank: e.g.: EU266611 | Sutherland et al. 2010 | [159] |

| P. ovale wallikeri | PCR | Saralamba et al. 2019 | [185] | ||

| India | P. ovale curtisi | Sequence | GenBank: e.g.: KU510234; KP050460 | Chavatte et al. 2015; Krishna et al. 2017 | [170, 186] |

| P. ovale wallikeri | Sequence | Mono infection, Bastar division of Chhattisgarh state, GenBank: KM873370 | Chaturvedi et al. 2015 | [83] | |

| P. ovale curtisi | Sequence | Mono infection, Bastar division of Chhattisgarh state, GenBank: KM288710 | Chaturvedi et al. 2015 | [83] | |

| Indonesia | P. ovale curtisi | Sequence | Sumatra,—GenBank: e.g.: KP050463 | Chavatte et al. 2015 | [170] |

| P. ovale wallikeri | Sequence | GenBank: e.g.: AB182497 | Win et al. 2004 | [167] | |

| Kenya | P. ovale curtisi | Sequence | GenBank: e.g.: KM494987 | Miller et al. 2015 | [186] |

| P. ovale wallikeri | Sequence | GenBank: e.g.: KM494986 | Miller et al. 2015 | [186] | |

| Laos | P. ovale curtisi | Sequence | Toma et al. 1999 | [188] | |

| P. ovale wallikeri | Sequence | Toma et al. 1999 | [188] | ||

| P. ovale sp. | PCR | 0.04% (1/2409) participants | Iwagami et al. 2018 | [189] | |

| Liberia | P. ovale curtisi | Sequence | GenBank: e.g.: KP050457 | Chavatte et al. 2015 | [170] |

| P. ovale wallikeri | Sequence | GenBank: e.g.: KP050382 | Chavatte et al. 2015 | [170] | |

| Madagascar | P. ovale curtisi | Randriamiarinjatovo 2015 | [190] | ||

| P. ovale wallikeri | Sequence | GenBank: e.g.: FJ409570 | Duval et al. 2009 | [163] | |

| P. ovale sp. | PCR | 1.4% (8/559) of malaria positives; 2 mono infections | Mehlotra et al. 2019 | [91] | |

| Malawi | P. ovale curtisi | PCR | 2 isolates | Oguike and Sutherland 2015 | [181] |

| P. ovale wallikeri | PCR | 2 isolates | Oguike and Sutherland 2015 | [181] | |

| Malaysia | P. ovale sp. (P. ovale curtisi) | PCR | 0.17% (1/585) asymptomatic; 5.3% (1/19) of malaria positives; primers rOVA1/rOVA2 | Noordin et al. 2020 | [191] |

| P. ovale curtisi | Sequence | Pahang; GenBank: MK351321 | unpublished | – | |

| P. ovale sp. | PCR | 0.4% (2/457) malaria positives | Yusof et al. 2014 | [192] | |

| Mali | P. ovale wallikeri | Sequence | GenBank: e.g. FJ409566 | Duval et al. 2009 | [163] |

| P. ovale curtisi | PCR | 0.49% (3/603) in pregnant women; 1 mono + 2 mixed | Williams et al. 2016 | [44] | |

| P. ovale wallikeri | PCR | 0.49% (3/603) in pregnant women; 3 mixed | Williams et al. 2016 | [44] | |

| Mauritania | P. ovale sp. | Microscopy | Asymptomatic; Sahelian zone 0.47% (5/1056); Saharan zone 0.18% (2/1059); Sahelo-Saharan zone 0.37% (5/1330) | Ouldabdallahi Moukah et al. 2016 | [97] |

| P. ovale curtisi | PCR | Imported to France | Joste et al. 2021 | [183] | |

| Mayotte | P. ovale sp. | Regional Health Agency | 0.4% of malaria cases | Maillard et al. 2015 | [99] |

| Mozambique | P. ovale curtisi | Sequence | GenBank: e.g. GU723517 | Sutherland et al. 2010 | [159] |

| P. ovale curtisi | PCR | Imported to China | Cao et al. 2016 | [90] | |

| P. ovale wallikeri | PCR | Imported to France and Spain |

Rojo-Marcos et al. 2014, Joste et al. 2021 |

[183, 193] | |

| Namibia | P. ovale curtisi | PCR | 0.31% (of 952) children < 9 years | Haiyambo et al. 2019 | [194] |

| Niger | P. ovale sp. | Microscopy | 1 case | Doudou et al. 2012 | [102] |

| P. ovale curtisi | PCR | Imported to France | Joste et al. 2021 | [183] | |

| P. ovale wallikeri | PCR | Imported to France | Joste et al. 2021 | [183] | |

| Nigeria | P. ovale curtisi | Sequence | GenBank: e.g.: GU723534; KP050374 |

Sutherland et al. 2010; Chavatte et al. 2015 |

[159, 170] |

| P. ovale wallikeri | Sequence | GenBank: e.g.: GU723579 | Sutherland et al. 2010 | [159] | |

| P. ovale sp. | PCR | 24% of malaria positives | Abdulraheem et al. 2019 | [106] | |

| P. ovale curtisi | PCR | 1.1% (4/365) malaria positive children | Oyedeji et al. 2021 | [195] | |

| P. ovale curtisi | PCR | Imported to China, France and Spain |

Cao et al. 2016; Joste et al. 2021; Rojo-Marcos et al. 2014 |

[90, 183, 193] | |

| P. ovale wallikeri | PCR | Imported to China, France and Spain |

Cao et al. 2016; Joste et al. 2021; Rojo-Marcos et al. 2014 |

[90, 183, 193] | |

| Pakistan | P. ovale sp. | PCR | Imported to China | Cao et al. 2016 | [90] |

| Papua New Guinea | P. ovale curtisi | Sequence | GenBank: e.g.: AF145337 | Mehlotra et al. 2002 | [196] |

| P. ovale wallikeri | Sequence | GenBank: e.g.: EU266603 | Sutherland et al. 2010 | [159] | |

| P. ovale sp. | PCR | 3.4% of 504 children aged 5–10 y from East Sepik Province | Robinson et al. 2015 | [197] | |

| Philippines | P. ovale sp. | Rare, Palawan only until 1977 | Cabrera and Arambulo 1977 | [200] | |

| P. ovale sp. | PCR | Palawan—0.3% (2/613) | Reyes et al. 2021 | [199] | |

| Rwanda | P. ovale wallikeri | PCR | Imported to France | Joste et al. 2021 | [183] |

| P. ovale wallikeri | Sequence | GenBank: e.g.: FJ409570 | Duval et al. 2009 | [163] | |

| P. ovale sp. | PCR | 4.9% (53/1089) schoolchildren | Sifft et al. 2016 | [200] | |

| Sao Tome and Principe | P. ovale curtisi | Sequence | GenBank: e.g.: GQ231520 | Sutherland et al. 2010 | [159] |

| P. ovale wallikeri | Sequence | GenBank: e.g.: EU266603 | Sutherland et al. 2010 | [159] | |

| P. ovale sp. | PCR | 2.8% of 661 | Pinto et al. 2000 | [201] | |

| Senegal | P. ovale curtisi | Sequence | GenBank: e.g.: KX417703 | unpublished | – |

| P. ovale wallikeri | Sequence | GenBank: e.g.: KX417699 | unpublished | – | |

| P. ovale sp. | PCR | 4.91% (6/122) | Badiane et al. 2021 | [116] | |

| P. ovale curtisi | PCR | Imported to France | Joste et al. 2021 | [183] | |

| P. ovale wallikeri | PCR | Imported to France | Joste et al. 2021 | [183] | |

| Sierra Leone | P. ovale curtisi | Sequence | GenBank: e.g.: GU723523 | Sutherland et al. 2010 | [159] |

| P. ovale wallikeri | Sequence | GenBank: e.g.: GU723571 | Sutherland et al. 2010 | [159] | |

| P. ovale curtisi | PCR | Imported to France | Joste et al. 2021 | [183] | |

| P. ovale wallikeri | PCR | Imported to France | Joste et al. 2021 | [183] | |

| P. ovale sp. | PCR | 0.4% (2/534) febrile patients | Leski et al. 2020 | [118] | |

| Solomon Islands | P. ovale wallikeri | PCR | Echeverry et al. 2016; Echeverry et al. 2017 | [202, 203] | |

| P. ovale sp. | PCR | 0.05% (1/1914) | Russell et al. 2021 | [204] | |

| Somalia | P. ovale sp. | Imported to USA (military) | CDC 1993 | [205] | |

| South Africa | P. ovale sp. | PCR | Imported to China | Cao et al. 2016 | [90] |

| South Sudan | P. ovale sp. | Microscopy | Bor; 1.2% of 392 | Omer et al. 1978 | [121] |

| Sri Lanka | P. ovale curtisi | PCR | 1 isolate in meta-analysis; Sri Lanka malariafree since 2016 | Bauffe et al. 2012 | [164] |

| Sudan | P. ovale sp. | Microscopy | New Halfa, 2% of 190 malaria positives | Himeidan et al. 2005 | [206] |

| P. ovale sp. | Microscopy | Khartoum; 0.32% of 3791 participants | El Sayed et al. 2000 | [207] | |

| P. ovale sp. | PCR | Imported to China | Cao et al. 2016 | [90] | |

| Tanzania | P. ovale curtisi | Sequence | GenBank: e.g.: GU723515 | Sutherland et al. 2010 | [159] |

| P. ovale wallikeri | PCR | 1 isolate | Calderaro et al. 2013 | [208] | |

| P. ovale wallikeri | PCR | 2 cases, Imported to France | Joste et al. 2021 | [183] | |

| P. ovale sp. | PCR | Zanzibar; 16.2% (30/185) malaria PCR positives; 10 mono + 20 mixed infections | Cook et al. 2015 | [209] | |

| Thailand | P. ovale curtisi | Sequence | GenBank: e.g.: KC137349; KF018432 | Putaporntip et al. 2013; Tanomsing et al. 2013 | [210, 211] |

| P. ovale wallikeri | Sequence | GenBank: e.g.: GQ231519; KC137344; KF018430 | Sutherland et al. 2010; Putaporntip et al. 2013; Tanomsing et al. 2013 | [159, 210, 211] | |

| P. ovale sp. | PCR | 0.3% (4/1347) asymptomatic participants; 4 mixed infections | Baum et al. 2016 | [212] | |

| Togo | P. ovale sp. | 2.8% | Gbary et al. 1988 | [213] | |

| P. ovale sp. | 2% of malaria positives | MSPS 2017 | [214] | ||

| P. ovale curtisi | PCR | 12 cases, Imported to France | Joste et al. 2021 | [183] | |

| P. ovale wallikeri | PCR | 14 cases, Imported to France | Joste et al. 2021 | [183] | |

| Uganda | P. ovale curtisi | Sequence | GenBank: e.g.: GU723521 | Sutherland et al. 2010 | [159] |

| P. ovale wallikeri | Sequence | GenBank: e.g.: GU723573; KP050464 |

Chavatte et al. 2015; Sutherland et al. 2010 |

[159, 170] | |

| P. ovale curtisi | PCR | Apac District; Buliisa District; Mayuge District | Oguike et al. 2011 | [175] | |

| P. ovale wallikeri | PCR | Apac District; Buliisa District; Mayuge District | Oguike et al. 2011 | [175] | |

| P. ovale sp. | PCR | 0–6.7% of all malaria; 0–4.3% of population | Oguike et al. 2011 | [175] | |

| P. ovale sp. | PCR | Imported to China | Cao et al. 2016 | [90] | |

| Vietnam | P. ovale curtisi | Sequence | GenBank: e.g.: GU723523 | Sutherland et al. 2010 | [159] |

| P. ovale wallikeri | Sequence | GenBank: e.g.: AF387041 | Unpublished | – | |

| P. ovale sp. | PCR | 0.8% (19/2303) of population | Nguyen et al. 2012 | [137] | |

| Yemen | P. ovale sp. | Microscopy | 1 symptomatic case, Beni-Hussan village | Al-Maktari and Bassiouny 1999 | [215] |

| Zambia | P. ovale wallikeri | PCR | 1 case | Nolder et al. 2013 | [168] |

| P. ovale wallikeri | LAMP | eastern Zambia | Hayashida et al. 2017 | [216] | |

| P. ovale curtisi | LAMP | eastern Zambia | Hayashida et al. 2017 | [216] | |

| P. ovale sp. | LAMP | 10.6% in asymptomatic participants | Hayashida et al. 2017 | [216] | |

| P. ovale sp. | PCR | Western province (cross-sectional survey); 12.4% (32/259); 6 mono + 26 mixed | Sitali et al. 2019 | [141] | |

| Zimbabwe | P. ovale wallikeri | Sequence | GenBank: e.g.: FJ409570 | Duval et al. 2009 | [163] |

| P. ovale sp. | < 2% of malaria positives | Taylor 1985 | [217] |

Genomic studies of P. o. curtisi and P. o. wallikeri

In the period since the two genetically distinct forms of P. ovale spp. were recognized, there have been a limited number of studies that have explored the differences between them. A study in UK travellers with ovale malaria by Nolder and colleagues could not identify any robust features of morphology that can distinguish P. o. curtisi from P. o. wallikeri [168], but were able to provide evidence of a significant difference in the distribution of relapse periodicity: the former species displayed a geometric mean latency of 85.7 days (95% CI 66.1 to 111.1, N = 74), compared to the significantly shorter 40.6 days (95% CI 28.9 to 57.0, N = 60) of the latter. This contrasts with the earlier observation of Chin and Coatney, who conducted studies of experimentally infected volunteers whose initial infections (all with the same “West African strain”) were treated with quinine or chloroquine before extended follow-up for evidence of P. vivax-type relapse [218]. These authors concluded that “These results leave little doubt that ovale malaria is a relapsing disease, but there appears to be no definite relapse pattern…” Subsequent studies in European travellers, a group in which super-infection is absent as a potential confounder, have confirmed this difference in latency period between P. ovale curtisi and P. ovale wallikeri [168, 219, 220]. These studies were also consistent in finding that P. ovale wallikeri is associated with low platelet counts and thus more likely to elicit clinical thrombocytopenia, and more likely to be correctly identified by immunochromatographic lateral flow tests that detect the LDH antigen, which fail to identify > 90% of P. ovale curtisi infections, a reflection of differences in the amino acid sequence of LDH in the two species [158, 159].

Given the absence of distinguishing morphological characters, despite reliable differences in some clinical and diagnostic features, there has been increasing attention to characterisation of the genomic organisation of the two sibling species as a route to better understanding their divergence from each other, and to describe the level of within-species diversity. Initial efforts were based on direct sequencing of PCR-amplified loci, and gave a general picture of fixed differences in both synonymous and non-synonymous substitutions between the species in almost every coding region examined, but very little intra-species genetic diversity [159–161, 185, 210, 211]. This was also true of genes related to sexual stage development, which had been examined for evidence of a mating barrier between the two species [181]. Whole genome analysis would clearly be very informative, but very few draft genomes of either species are available due to the difficulty in obtaining parasite DNA from these typically very low parasitaemia infections. The first partial genomes to become available were assembled from Illumina short-read sequencing of two isolates of P. o. wallikeri from Chinese workers returning from West Africa, as well as one P. o. curtisi isolate also from a Chinese worker returning from West Africa and the genome of the chimpanzee-propagated Nigeria I strain [1, 22, 24]. Subsequently, three partial genomes of P. o. curtisi from two patients that tested positive for P. falciparum in Ghana and one mixed infection from Cameroon, together with two P. o. wallikeri genomes obtained from individual patients in Cameroon, were also assembled [23].

Analysis of the P. ovale spp. genomes published to date has estimated a total genome length for both species of ~ 35 Mbp (29% GC content), with 40% being subtelomeric [22, 23]. Differences in total length (maximum observed 38Mbp) were observed between isolates, primarily due to differences in the estimated size of expansion of the ocir/owir gene families. These species have considerably more pir genes (1500–2000), than other human plasmodium parasites (~ 300) [25]. A larger number of surfin genes have also been identified, with > 50 present in P. o. curtisi and > 125 in P. o. wallikeri. The variant protein isoforms expressed by members of these gene families may be important for interactions with multiple host ligands and, as they are likely to be antigenically variant, their expansion is thought to have been driven by host immune pressure. Expansion of reticulocyte binding-like proteins (RBP), involved in red blood cell invasion, has been observed in both ovale genomes (13–14 genes), gene copy numbers similar to P. vivax, while in other species only ~ 2–8 copies have been identified. An expansion of the Plasmodium ookinete surface protein P28 appears to be a specific feature of both P. ovale spp, as only one copy appears to exist in the genomes of other human-infecting species in the genus.

All the available data confirm that there is a close genetic relationship between the two species, supported by phylogenetic analysis that show P. o. curtisi and P. o. wallikeri grouping together in the same clade in all studies to date [2, 23, 159]. However, many differences between the two taxa have been observed when comparing surfin, pir and rbp genes, as isoforms with identical sequences have been observed between isolates of the same species, but these families are far more divergent in between-species comparisons of the few P. o. curtisi and P. o. wallikeri genomes assembled so far. Significant dimorphism has previously been reported in candidate genes across larger datasets from Asian and African isolates [159–161, 175, 185, 210, 211]. For example, specific analysis of nucleotide sequences of five protein-coding regions, likely involved in life cycle sexual stages and so potentially contributing to mating barriers, found that intra-species variation was minimal at each locus, but clear dimorphism were detected when comparing P. o. curtisi to P. o. wallikeri [181]. Similar results were observed across three vaccine candidate surface proteins in samples collected from Thailand and countries in Africa [185], and in multi-locus sequence analyses reported in a large study of both species in Bangladesh [161]. To better understand the intra- and inter -genetic diversity of these species, more complete reference genomes are needed, as well as a much greater number of isolates undergoing whole genome sequencing across geographic regions.

Likely origin of these two closely-related, sympatric and non-recombining species

The question as to how two non-recombining sibling species have ended up co-circulating in the same mammalian hosts, transmitted by the same arthropod vectors, has attracted some attention, as has the difficulty in estimating when the two lineages diverged, and in which primate hosts [2, 3, 23, 25, 159]. A thorough summary of the current thinking can be found therein, but the most parsimonious explanation for the current co-circulation of P. o. curtisi and P. o. wallikeri, in what appears to be perfect sympatry, can be paraphrased from reference 26: pre-ovale parasites in an unknown non-human primate host underwent an initial host transition into hominids some millions of years before the present. This new lineage thus began from a single event, representing an extreme genetic bottleneck, and developed apart from the progenitor stock. Substantial genetic drift occurred, while the two parasite lineages were partitioned in different hosts, a form of allopatry. When a second transition into hominid hosts occurred, again through an extreme genetic bottleneck, both lineages now shared the same hosts, but there was insufficient genetic similarity for fertilisation, meiotic pairing and recombination to occur. However, as the two new species shared almost all features of biology and life history, they together flourished in settings where conditions were favourable and appropriate vectors abundant, and both perished where conditions were harsh. This provides a plausible scenario to explain the contemporary observation that P. o. curtisi and P. o. wallikeri are now always found co-circulating in the same host and vector populations. Considering these observations, and the irrefutable evidence assembled since 2010 that the ovale parasites represent two distinct sibling species, it is clear that the trinomial nomenclature currently in use is not fit for purpose. Some of the arguments around this can be found in Box 2 of reference 26; to resolve this situation, the current authors and collaborators have developed a proposed solution in which two new binomials are utilized in place of the current nomenclature (manuscript in preparation). In the meantime, correspondence on this topic is most welcome.

As to the evolutionary origins of the ovale parasites, despite twentieth century phylogenetic analyses in general favouring kinship with P. vivax [1, 221], genomic sequencing and elucidation of nuclear protein-coding, ribosomal RNA-coding, and mitochondrial genes have more recently placed these species distant from the vivax clade, which includes P. cynomolgi, P. knowlesi and other SE Asian parasites of simian hosts. Rather a position closer to P. malariae [159], Lemuroidea [222], or perhaps the rodent parasite clade [23], have also been put forward. As more genomic information becomes available for P. o. curtisi and P. o. wallikeri the kinship of these species, and therefore identification of their closest contemporary relatives, should become clearer.

Concluding remarks

Multi-population genomic studies of the neglected malaria parasites considered here are essential to provide insights into the biology underlying mechanisms of infection, disease progression and adaptation to different hosts. Many questions, for these and other Plasmodium species, remain answered, including the ability of some species to form dormant stages in the liver (hypnozoites) as observed for P. vivax and P. ovale species, and suggested as also possible for P. malariae [26], and the regulation of the blood stage cycles that can differ among species (e.g., P. malariae has a quartan cycle, a quotidian cycle is observed for P. knowlesi, while the other primate species all follow a tertian cycle).

Although genomics studies of these parasites have been difficult, the development of new assays such as SWGA allow the whole genome sequencing of parasite DNA from clinical samples [21], and have therefore opened up new opportunities to understand genomic diversity. Sequencing developments, such as real-time selective sequencing using Nanopore technology, will favour the selection of parasite DNA molecules for sequencing while excluding human molecules [223]. Phenotypic studies of important characters such as drug susceptibility are challenging for these species [224], but the recently developed strategy of “orthologue exchange” now permits detailed in vitro studies of gene function for every species, using transgenic lines with P. falciparum or P. knowlesi as the recipient parasite cell. These and future advances can support the large-scale and cost-effective genomic studies of neglected malaria that are now needed. The resulting gains in knowledge will greatly assist the design of species-specific diagnostics, treatments, and surveillance tools, thereby supporting malaria elimination goals.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the ERASMUS Plus programme for funding a visit by H-PF to London in 2017. CJS is supported by the UK Health Security Agency, the EDCTP WANECAM II Project and the Medical Research Council. SC is supported by Research England Bloomsbury SET Project Grant CCF17-7779.

Author contributions

All three authors together wrote the first draft and edited the final draft.

Funding

CJS is supported by the UK Health Security Agency, the EDCTP WANECAM II Project and the UK Medical Research Council. SC is supported by Research England Bloomsbury SET Project Grant CCF17-7779.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Coatney GR, Collins WE, Warren M, Contacos PG. The primate malarias. 1st edn. Bethesda, MD: US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; 1971. Digital Version 1.0. Atlanta, GA: CDC; 2003.

- 2.Sharp PM, Plenderleith LJ, Hahn BH. Ape origins of human malaria. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2020;74:39–63. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-020518-115628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sutherland CJ, Polley SD. Genomic insights into the past, current, and future evolution of human parasites of the genus Plasmodium. In: Tibayrenc M, editor. Genetics and Evolution of Infectious Diseases (Second Edition). Elsevier; 2017. p. 487-507. 10.1016/B978-0-12-799942-5.00021-4

- 4.Gonder R, Berenberg-Gossler von HV. Untersuchungen uber Malaria-Plasmodien der Affen. Malaria-Intern. Arch. Leipzig. 1908:47–56.

- 5.Carrillo-Bilbao G, Martin-Solano S, Saegerman C. Zoonotic blood-borne pathogens in non-human primates in the Neotropical Region: a systematic review. Pathogens. 2021;10:1009. doi: 10.3390/pathogens10081009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abreu FVS, Santos ED, Mello ARL, Gomes LR, Alvarenga DAM, Gomes MQ, et al. Howler monkeys are the reservoir of malarial parasites causing zoonotic infections in the Atlantic forest of Rio de Janeiro. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13:e0007906. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0007906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fandeur T, Volney B, Peneau C, de Thoisy B. Monkeys of the rainforest in French Guiana are natural reservoirs for P. brasilianum/P. malariae malaria. Parasitology. 2000;120:11–21. doi: 10.1017/S0031182099005168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rondón S, León C, Link A, González C. Prevalence of Plasmodium parasites in non-human primates and mosquitoes in areas with different degrees of fragmentation in Colombia. Malar J. 2019;18:276. doi: 10.1186/s12936-019-2910-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Araújo MS, Messias MR, Figueiró MR, Gil LH, Probst CM, Vidal NM, et al. Natural Plasmodium infection in monkeys in the state of Rondônia (Brazilian Western Amazon) Malar J. 2013;12:180. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-12-180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alvarenga DA, Pina-Costa A, Bianco C, Jr, Moreira SB, Brasil P, Pissinatti A, et al. New potential Plasmodium brasilianum hosts: tamarin and marmoset monkeys (family Callitrichidae) Malar J. 2017;16:71. doi: 10.1186/s12936-017-1724-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Erkenswick GA, Watsa M, Pacheco MA, Escalante AA, Parker PG. Chronic Plasmodium brasilianum infections in wild Peruvian tamarins. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0184504. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0184504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guimarães LO, Wunderlich G, Alves JM, Bueno MG, Röhe F, Catão-Dias JL, et al. Merozoite surface protein-1 genetic diversity in Plasmodium malariae and Plasmodium brasilianum from Brazil. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15:529. doi: 10.1186/s12879-015-1238-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lalremruata A, Magris M, Vivas-Martínez S, Koehler M, Esen M, Kempaiah P, et al. Natural infection of Plasmodium brasilianum in humans: Man and monkey share quartan malaria parasites in the Venezuelan Amazon. EBioMedicine. 2015;2:1186–1192. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2015.07.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Escalante AA, Barrio E, Ayala FJ. Evolutionary origin of human and primate malarias: evidence from the circumsporozoite protein gene. Mol Biol Evol. 1995;12:616–626. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lal AA, de la Cruz VF, Collins WE, Campbell GH, Procell PM, McCutchan TF. Circumsporozoite protein gene from Plasmodium brasilianum Animal reservoirs for human malaria parasites? J Biol Chem. 1988;263:5495–5498. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)60590-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tazi L, Ayala FJ. Unresolved direction of host transfer of Plasmodium vivax v. P. simium and P. malariae v. P. brasilianum. Infect Genet Evol. 2011;11:209–221. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2010.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Castro Duarte AM, Malafronte Rdos S, Cerutti C, Jr, Curado I, de Paiva BR, Maeda AY, et al. Natural Plasmodium infections in Brazilian wild monkeys: reservoirs for human infections? Acta Trop. 2008;107:179–185. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2008.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fuentes-Ramírez A, Jiménez-Soto M, Castro R, Romero-Zuñiga JJ, Dolz G. Molecular detection of Plasmodium malariae/Plasmodium brasilianum in non-human primates in captivity in Costa Rica. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0170704. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0170704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guimarães LO, Bajay MM, Wunderlich G, Bueno MG, Röhe F, Catão-Dias JL, et al. The genetic diversity of Plasmodium malariae and Plasmodium brasilianum from human, simian and mosquito hosts in Brazil. Acta Trop. 2012;124:27–32. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2012.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Talundzic E, Ravishankar S, Nayak V, Patel DS, Olsen C, Sheth M, et al. First full draft genome sequence of Plasmodium brasilianum. Genome Announc. 2017;5:e01566–e1616. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.01566-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ibrahim A, Diez Benavente E, Nolder D, Proux S, Higgins M, Muwanguzi J, et al. Selective whole genome amplification of Plasmodium malariae DNA from clinical samples reveals insights into population structure. Sci Rep. 2020;10:10832. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-67568-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ansari HR, Templeton TJ, Subudhi AK, Ramaprasad A, Tang J, Lu F, et al. Genome-scale comparison of expanded gene families in Plasmodium ovale wallikeri and Plasmodium ovale curtisi with Plasmodium malariae and with other Plasmodium species. Int J Parasitol. 2016;46:685–696. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2016.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rutledge GG, Böhme U, Sanders M, Reid AJ, Cotton JA, Maiga-Ascofare O, et al. Plasmodium malariae and P. ovale genomes provide insights into malaria parasite evolution. Nature. 2017;542:101–104. doi: 10.1038/nature21038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Collins WE, Jeffery GM. Plasmodium malariae: parasite and disease. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007;20:579–592. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00027-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sutherland CJ. Persistent parasitism: the adaptive biology of malariae and ovale malaria. Trends Parasitol. 2016;32:808–819. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2016.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Teo BH, Lansdell P, Smith V, Blaze M, Nolder D, Beshir KB, et al. Delayed onset of symptoms and atovaquone-proguanil chemoprophylaxis breakthrough by Plasmodium malariae in the absence of mutation at codon 268 of pmcytb. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9:e0004068. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dinko B, Oguike MC, Larbi JA, Bousema T, Sutherland CJ. Persistent detection of Plasmodium falciparum, P. malariae, P. ovale curtisi and P. ovale wallikeri after ACT treatment of asymptomatic Ghanaian school children. Int J Parasitol Drugs Drug Resist. 2013;3:45–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpddr.2013.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Betson M, Sousa-Figueiredo JC, Atuhaire A, Arinaitwe M, Adriko M, Mwesigwa G, et al. Detection of persistent Plasmodium spp. infections in Ugandan children after artemether-lumefantrine treatment. Parasitology. 2014;141:1880–1890. doi: 10.1017/S003118201400033X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lubis IND, Wijaya H, Lubis M, Lubis CP, Beshir KB, Staedke SG, et al. Recurrence of Plasmodium malariae and P. falciparum following treatment of uncomplicated malaria in North Sumatera with dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine or artemether-lumefantrine. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofaa116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Langford S, Douglas NM, Lampah DA, Simpson JA, Kenangalem E, Sugiarto P, et al. Plasmodium malariae infection associated with a high burden of anemia: a hospital-based surveillance study. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9:e0004195. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]