Abstract

Accurate measurement of stalking has proven difficult, partly because stalking is characterised by the cumulative effects of a pattern of behaviour. This study aimed to develop and evaluate a new measure of stalking that overcomes the observed shortcomings of existing tools. The Stalking Assessment Indices (SAI) were created using index development principles and evaluated in 244 Australian undergraduate students (Mage= 33.7, 77% female). Seventy-three reported stalking victimisation (experiencing at least five intrusions over at least two weeks causing substantial fear or distress), and 51 reported stalking perpetration. Stalking behaviours reported by victims formed a two-component structure, which was also observed in multidimensional scaling analysis. The perpetration index showed good convergent validity with measures of rumination and aggression, and both indices had adequate test–retest reliability over four weeks. These results suggest that the SAI could provide a consistent and inclusive measure of stalking for use across different research settings.

Keywords: harassment, index development, intimate partner abuse, measurement, obsessive relational intrusion, stalking, unwanted pursuit behaviour

Scholars have identified stalking victimisation and perpetration in a variety of ways since research into the phenomena began in the early 1990s. These include lengthy surveys (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 1996; Budd & Mattinson, 2000; Purcell, Pathé, & Mullen, 2002; Sheridan, Gillett, & Davies, 2000; Sheridan & Roberts, 2011), direct queries about stalking experiences (Bjerregaard, 2000; Fremouw, Westrup, & Pennypacker, 1997), vignettes and case studies (Scott, Rajakaruna, Sheridan, & Sleath, 2014; Scott & Sheridan, 2011), legal definitions or convictions (McEwan, Harder, Brandt, & de Vogel, 2020; McEwan, Mullen, MacKenzie, & Ogloff, 2009; Mullen, Pathé, Purcell, & Stuart, 1999; Nijdam-Jones, Rosenfeld, Gerbrandij, Quick & Galietta, 2018; Rosenfeld & Harmon, 2002), and over the past 25 years an increasing array of questionnaires (e.g. Coleman, 1997; Cupach & Spitzberg, 2004; Langhinrichsen-Rohling, Palarea, Cohen, & Rohling, 2000; McNamara & Marsil, 2012; Nobles, Fox, Piquero, & Piquero, 2009; Senkans, McEwan, & Ogloff, 2017; Spitzberg & Cupach, 2014; Tjaden & Thoennes, 1998; Turmanis & Brown, 2006). In 2011 Fox, Nobles and Fisher conducted a comprehensive review and evaluation of stalking measurement (Fox, Nobles, & Fisher, 2011), identifying methodological or practical flaws in each of these approaches. They highlighted some key challenges when measuring stalking, including inconsistency in definition, the normative nature of many individual stalking behaviours, and the multidimensional structure of the construct. The most complicated aspect of definition and measurement identified by Fox and colleagues is that stalking exists in the cumulative effect of multiple behaviours on the target over time, rather than in any single act. The emergent and evolving nature of stalking has proven difficult to operationalise for scientific purposes and continues to present a challenge for the field of stalking research.

Fox et al. (2011) concluded that there was a need for ‘consistent and inclusive measurement strategies’ that could help to ‘develop a richer body of knowledge’ about stalking (p. 83). They made specific recommendations to improve stalking measurement, including the need to assess measures for validity and reliability, to use specified timeframes for measurement to reduce time-order problems and to include measurement items that build on existing research. However, the majority of research in the past decade has continued to use methodologies inconsistent with some or all of these recommendations. Drawing on Fox and colleagues’ review and recommendations, the current study aimed to develop and evaluate a new instrument that could meet their call for an ‘inclusive and consistent’ measure, thereby strengthening future research into stalking.

Defining stalking

Stalking was described legally before it emerged in a detailed way in scientific or social discourse, making the elements of stalking laws fundamental to defining the construct. The first modern stalking law was introduced in California in 1990, then around most of the Anglophone world, much of Europe, and parts of Africa and Asia throughout the 1990s and 2000s (though not without controversy; Dennison & Thomson, 2005; Van der Aa, 2018). The rapid proliferation of stalking laws and the challenges of legislating this newly recognised phenomenon meant that there was no single legal construction of stalking that could be easily adapted for scientific research (McAnaney, Curliss, & Abeyta-Price, 1993).

Stalking is difficult to legislate against because it involves many otherwise innocuous behaviours. Although some stalkers are overtly threatening or violent, many stalking behaviours are part of everyday interaction: telephone calls, social media contacts, sending gifts, waiting for someone at their home. As noted by McEwan, Mullen, and MacKenzie (2007), stalking is qualitatively different from the legitimate pursuit of a complaint or acceptable attempts to reconcile a failed relationship, but it has proven difficult for legislators to specify in a consistent way where legitimate pursuit ends and stalking begins.

While jurisdictions vary in how they define stalking, there are commonalities that can guide those designing stalking measures. Stalking laws typically involve at least two and potentially three elements: (a) the pattern and nature of the unwanted behaviour (the conduct element); (b) the intent of the perpetrator (the mental element); and often, though not always, (c) some requirement for a negative impact on the target of the stalking (the impact, or harm, element). Different laws have defined these three elements in different ways and with different levels of specificity (see Fox et al., 2011; McEwan et al., 2007; Van der Aa, 2018).

The variation in legal constructions of stalking presents a significant challenge for researchers attempting to define stalking in a general way for scientific purposes. The most common solution has been to develop definitions that sit alongside legal codes, attempting to capture at least one of the three core elements above without specifically adhering to a single law. Fox et al. (2011) suggested that the most stringent research into stalking victimisation and perpetration should assess all three elements to establish the presence of stalking. Research defining stalking in this rigorous way has the greatest chance of reflecting the kinds of cases that come before courts, while research that does not adhere to at least the conduct element does not measure stalking, but discrete acts that may not constitute a stalking episode (Nobles et al., 2009).

Measuring conduct, impact and intent

The conduct element is relatively easy to translate from the legal realm into research. Most laws define the repetition component of the course of conduct in a reasonably consistent (though exceedingly broad) way as at least two unwanted acts. This can be translated into a measurement tool by asking about the frequency of different types of unwanted intrusions committed by a person, with multiple experiences of a single behaviour or endorsement of more than one unwanted behaviour equating to stalking. However, given that research has shown that a small number of unwanted contacts is normative when attempting to commence or after the end of a relationship (De Smet, Uzieblo, Loeys, Buysse, & Onraedt, 2015; Sinclair & Frieze, 2000; Thompson & Dennison, 2008), it is arguable whether repetition alone should be used to define stalking. It is therefore essential to combine conduct with some measure of victim impact or perpetrator intent when identifying a pattern of behaviour as stalking.

Ascertaining a negative effect on the victim is also straightforward when measuring victimisation, as the question can be directly asked. The presence of a course of conduct can then be combined with the effect of the conduct on the respondent to determine whether stalking victimisation has occurred. Additional criteria (such as the duration of the course of conduct, or the presence of threats) could be added to more closely reflect local legal definitions as desired.

Ascertaining impact on the victim when measuring self-reported stalking perpetration poses more challenges. Some authors have applied the same criteria as those used to measure victimisation, requiring the respondent to identify patterns of behaviour that are frightening, unwanted, harassing or threatening (e.g. Fremouw et al., 1997; Nobles et al., 2009). However, this approach ignores the pitfalls of relying on perpetrators’ assessment of victims’ mental state. The tendency to preserve a positive self-image and the social undesirability of intending harm makes it likely that all but the most antisocial underestimate the distress or fear they cause (Mullen, Pathé, & Purcell, 2009; Thompson & Dennison, 2008). These same psychological characteristics make subjective self-report of intent similarly fraught. Thus, researchers may need to go beyond the three common elements of stalking legislation and rely on additional parameters when measuring self-reported stalking perpetration.

One potential way to resolve this issue is by using a measurable proxy for impact and intent, such as the duration of the episode of unwanted contact and/or the frequency of unwanted contact. Purcell, Pathé, and Mullen (2004) investigated whether it was possible to distinguish ‘brief outbursts of intrusiveness from damaging and persistent episodes of stalking’ (Purcell et al., 2004, p. 575) based on the reported duration of the episode. They re-analysed data from 432 people who had reported legally defined stalking (‘two or more’ intrusions) in their earlier epidemiological study of stalking victimisation in Victoria, Australia (Purcell et al., 2002). A duration of two weeks effectively discriminated between a problematic pattern of stalking and briefer forms of harassment. For the 55% (n = 236) of victims who were stalked for longer than two weeks, the median duration was six months (mode: 12 months) with a median of 20 unwanted intrusions. Equivalent figures for those harassed for under two weeks was two days (mode: one day) and five unwanted intrusions. Victimisation for over two weeks was associated with significantly greater levels of psychological and social impairment. Interpreting these results in the context of the wider representative sample (n = 1844) from which the study was drawn, a two-week duration threshold produced a stalking prevalence of 12.8%, compared to 23.4% using the legal definition. This study suggests that a two-week threshold may be an appropriate proxy for meaningful victim impact in self-report perpetration studies (Purcell et al., 2004). However, such a threshold means only two intrusions over the course of a two-week period could be labelled stalking, which may raise questions about the perpetrator’s continuity of purpose.

Another Australian study addressed this issue by examining the total number of unwanted intrusions as a way of differentiating stalking from more normative behaviour. Thompson and Dennison (2008) investigated perpetration of ‘unwanted post-relationship behaviour’ in a combined sample of 1738 university students and community members in Queensland. They found that violence and threats became more common as the threshold number of unwanted intrusions used to define stalking increased (35% of cases involving ≥2 intrusions, 40% of cases involving ≥5, and 50% of cases involving ≥10). The authors recommended ‘≥5 intrusive acts’ with no specified timeframe as a threshold for identifying stalking, on the basis that this captured the majority of individuals who reported violence or threats towards the target, which would be likely to instil fear or distress.

Thompson and Dennison (2008) recommended against using a duration threshold so as to capture a wider range of more severe behaviour. However, this leads to the possibility that very short-lived but highly repetitive and non-violent behaviour could be categorised as stalking (e.g. drunk dialling an ex-partner multiple times in a single evening). While this may appropriately be considered harassment, whether it should reach the threshold for stalking is unclear. Incorporating a duration criterion increases the chance that the behaviour would be likely to cause the necessary negative impact (reflecting Dennison & Thomson’s, 2002, finding that community members thought harm was more foreseeable as persistence of unwanted intrusions increased).

Given the relatively limited literature on proxies for victim impact and stalker intent, it seems reasonable to take a conservative approach until there is evidence for an alternative. At present, a combined behavioural threshold of at least five unwanted intrusions over a period of at least two weeks appears to be a reasonable way to define the presence of stalking in self-report perpetration studies in lieu of a reliable measure of impact or intent. Such an approach also has the benefit of capturing the ‘cumulativeness’ of stalking behaviours (Spitzberg & Cupach, 2014, p. 128), which seems most traumatising. Such a measure would need to be validated by comparing the self-report of people who also have an objective record of stalking, but it provides a starting point for measuring perpetration in a replicable way in non-forensic samples.

Other necessary features of a stalking measure

Assessing behaviour that is repeated, is unwanted, and has a negative impact (or a proxy of impact) is a useful first step in developing a measure of stalking, but challenges remain. Fox et al. (2011) identified three other key areas that required attention in the development of stalking victimisation and perpetration measures: measurement timeframe, format and content, and reliability and validity.

Measurement timeframe

Fox et al. (2011) recommended that future studies use measures that better control the timeframe in which stalking is studied. This would allow analyses of causal mechanisms, as well as examining co-occurring phenomena (e.g. symptoms of mental illness). Specifically, they recommended that future measures adopt timeframes that could assist with overcoming recall problems including: asking about stalking within the past year, enquiring specifically when the stalking commenced and stopped, and asking whether the stalking occurred before or after other events of interest. They suggested that the optimal design would be longitudinal, allowing for multiple data points on the same people within a single study, allowing for mapping of stalking experiences over time.

Relatively few subsequent studies appear to have adopted these recommendations. Edwards and Gidycz (2014) conducted a genuinely prospective study among 56 women who had ended a relationship in the four months prior, examining the association between post-separation stalking victimisation and a range of mental health outcomes. Other attempts to control for a specific timeframe include asking respondents to consider only stalking following the termination of a relationship in the past two years (Cupach, Spitzberg, Bolingbroke, & Tellitocci, 2011) or their most conflicted relationship (Senkans, McEwan, & Ogloff, 2017). However, it is still common to see reports of lifetime stalking prevalence without any further inquiry about when the stalking occurred. This is partially attributable to the continued use of adaptations of lifetime measures such as the National Violence Against Women Survey (NVAWS) to measure stalking (e.g. Chan & Sheridan, 2020; McNamara & Marsil, 2012; Nobles et al., 2018).

Measurement format and content

Fox et al. (2011) make a strong argument for the use of multiple-item measures of stalking. They note that this method permits replication, providing external validity as results can be generalised across settings. It also allows for more sophisticated analyses of what kinds of stalking behaviours are related to various victim and perpetrator outcomes. Fox et al. (2011) also specified that future measures should draw on items from existing tools to ensure that research outcomes are comparable over time. Research published since their review has generally reflected these recommendations. It is rare in contemporary research to see stalking measured with a single question, and many studies have used the same tools as in earlier research or made slight adaptations to their content (e.g. Brownhalls, Duffy, Eriksson, & Barlow, 2019; Nobles et al., 2018; Sheridan, North, & Scott, 2019; Spitzberg, Cupach, Hannawa, & Crowley, 2014).

Fox et al. (2011) also highlighted the need to develop a ‘core set of items’ (p. 82) that will allow for comparisons between samples drawn from different populations and over different timeframes. They identify a number of existing stalking measures that can be used to identify this core set of items, to which we would add examination of stalking legislation that specifies particular types of behaviour that constitute stalking. ‘Core’ stalking behaviours can also be identified statistically, using multi-dimensional scaling techniques to examine which items on a scale reliably cluster together in different samples or populations, providing evidence that they are common to most stalking episodes. To date, this recommendation has not been pursued.

Reliability and validity

Fox et al. (2011) observed that ‘both reliability and validity are frequently unaddressed in published studies, which cast[s] doubt on the adequacy of some measures, and consequently, the robustness of results’ (p. 80). Most existing measures have good face validity (though this is not always an advantage when measuring perpetration), but criterion validity and divergent or convergent validity are rarely reported. Fox and colleagues also recommended better reporting of reliability measures, such as Cronbach’s alpha, and suggested using factor analysis to assess reliability and validity by helping to determine whether indicators from a multiple-item scale load on a single latent construct.

Establishing reliability and validity of stalking measures is essential, but we suggest that metrics drawn from classical test theory (CTT), like those suggested by Fox et al. (2011), would be inappropriate. Classical test theory assumes that items from the same scale are caused by the same underlying variable. However, stalking is a consequence of behaviour, not a trait or latent construct that causes behaviour. Stalking is a formative construct that is composed of observable phenomena and does not exist in their absence, rather than a reflective construct that underpins observable phenomena and exists regardless of their presence (Bollen & Lennox, 1991; Diamantopoulos, Riefler, & Roth, 2008). Unlike reflective constructs, which are measured using scales, formative constructs are measured using indices. Index development does not share the assumptions of CTT. In fact, removal of items because of poor internal consistency (e.g. low Cronbach’s alpha) may reduce the validity of the index if a poorly correlating item is omitted that captures a unique characteristic of the formative construct (DeVellis, 2016).

Rather than classical measures of reliability and validity, index development involves: (a) specifying the breadth of the formative construct; (b) conducting a census of items that form the construct; (c) investigating item multicollinearity; and (d) examining items’ external validity (Diamantopoulos & Winklhofer, 2001). While the first two stages are theoretical, the latter two provide empirical evidence that the items are not redundant within the index and measure the full scope and nature of the formative construct.

If stalking is a formative construct that should be measured using an index, the high internal consistency evidenced by questionnaires such as the NVAWS does not necessarily reflect good measurement of the full breadth of the stalking construct. This has been recognised by some authors who have supplemented the NVAWS with additional items (Amar, 2006; McNamara & Marsil, 2012; Nobles et al., 2009). We propose that, rather than refining a stalking measure to the most parsimonious set of behavioural descriptors with high inter-correlations, a more appropriate way to measure the full breadth and range of stalking is to develop a multiple-item index or set of indices (depending on the underlying relationships between behaviours) that assesses the full formative construct.

Key measures of reliability and validity are still applicable to index development, such as test–retest reliability, criterion validity, and convergent and divergent validity. Those classified as stalkers by the index should score more highly than non-stalkers on theoretically related constructs (such as rumination or aggression; Birch, Ireland, & Ninaus, 2018; Spitzberg & Cupach, 2014), while those classified as stalking victims should report greater levels of trauma symptomatology than those classified as non-victims (Nobles et al., 2018; Purcell, Pathé, & Mullen, 2005).

Relationship context

In addition to the key features identified by Fox et al. (2011), we suggest that a useful measure of stalking should also establish the context of the relationship between perpetrator and victim. This is because the word ‘stalking’ is used to describe two somewhat distinct patterns of behaviour. The original conceptualisation of stalking restricted its use to behaviour occurring outside of a current intimate relationship (Coleman, 1997; Lowney & Best, 1995; McMahon, McGorrery, & Burton, 2020). In literature adhering to this conceptualisation, ‘stalking’ describes a person repeatedly imposing themselves into the life of another where they have no right to be, causing fear or distress. Stalking is therefore defined as any pattern of unwanted intrusive behaviour outside of an ongoing relationship, regardless of whether the perpetrator is a former intimate, an estranged family member or friend, an acquaintance or a stranger. Unwanted intrusive behaviour that occurs during an intimate relationship is conceptualised separately as intimate partner abuse. The links between the two patterns of behaviour are acknowledged, but different language is used to label and describe them as they are thought to have some distinct causes and require different types of assessment and management (for further discussion see Davis, Swan, & Gambone, 2012; Douglas & Dutton, 2001; McEwan, Shea, Nazarewicz, & Senkans, 2017; Senkans et al., 2017; Spitzberg & Cupach, 2014; White, Kowalski, Lyndon, & Valentine, 2000).

Another body of literature uses ‘stalking’ to denote a particular type of intimate partner abuse that occurs both within relationships and post-separation, with no differentiation between the two contexts. This approach emerged in the late 1990s, possibly stemming from the decision by the United States Centre for Disease Control to classify both current and former partners as victims of stalking in the 1995/96 National Crime Survey (Tjaden & Thoennes, 1998). This was a marked departure from surveys of stalking in other countries (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 1996; Budd & Mattinson, 2000; Morris, Anderson, & Murray, 2002) and catalysed a body of research that describes stalking specifically as a sub-category of intimate partner abuse (e.g. Backes, Fedina, & Holmes, 2020; Bendlin & Sheridan, 2019; Logan, Leukefeld, & Walker, 2000; Logan & Walker, 2009, 2010; McFarlane, Campbell, & Watson, 2002; Mechanic, Weaver, & Resick, 2000; Monckton-Smith, Szymanska, & Haile, 2017; Tjaden & Thoennes, 2000). Over the past decade, this conceptualisation has been integrated into the broader construct of coercive control, where the word ‘stalking’ is used in a restricted way to describe surveillance and monitoring of a current or former intimate partner (Stark, 2012; Stark & Hester, 2019). This body of literature ignores stalking that occurs in other relationship contexts.

Given that relationship context is so central to these different approaches, it seems an important piece of information for any stalking measure to collect. The most obvious way to achieve this is to provide respondents with a choice of common relationship contexts drawn from the research literature (e.g. current partner, ex-partner, acquaintance, stranger) and ask them to identify the nature of the relationship at the beginning of the stalking episode. This means that, regardless of how the authors of the study choose to define stalking and apply the findings to practice (including or excluding current intimate partners), they would be able to publish descriptive information about the relationship contexts of the stalking episodes they identify. This would also allow for useful research about whether social perceptions of stalking include behaviour during relationships, or whether stalking is generally understood as something that occurs outside of a relationship (see also McMahon et al., 2020).

The current study

In the decade since Fox et al.’s (2011) important critique, there has been limited methodological development in the field of stalking measurement. The limitations of existing measures mean that it continues to be difficult to compare findings across studies in different settings. They also present a barrier to more experimental research, as accurate ascertainment of victimisation and perpetration requires lengthy and detailed surveys, reducing the opportunity for collection of other data necessary to address questions derived from theory.

This study aims to develop and evaluate a new measure of stalking, drawing on Fox et al.’s (2011) recommendations. Our aim is to develop a reliable, valid and time-efficient measure of stalking victimisation and perpetration that can be used across research and practice settings. We aim to develop a transparent measure that can be adjusted if necessary to meet specific needs, but which can also be scored and reported in a consistent way to allow for comparison between samples.

Method

Participants

Participants were recruited from a large university in south-east Australia between May and September 2016. A total of 267 students responded to the online survey for course credits. After excluding participants who did not respond to the stalking measure, the final sample consisted of 244 students (188 female, 77%) with age ranging between 18 and 74 years (M = 33.7, SD = 11.7). The majority of participants were born in Australia (71.3%) and identified themselves as being of Australian (51.4%) or mixed Australian (e.g. Chinese-Australian; 17.6%) ethnicity, including 2.8% of the sample who reported Australian-Aboriginal ethnicity. Otherwise, 6.1% reported various European ethnicities, 5.7% identified as having Asian or South Asian ethnicities, and 2% identified as being of African ethnicities. Most participants identified as heterosexual (92.6%), with the remainder identifying as bisexual (4.1%), or gay or lesbian (3.3%). Fifty percent of participants reported that their highest qualification was a post-secondary school certificate or diploma, 27.5% had completed only secondary school, 16% had an undergraduate degree, and 5.7% had a postgraduate qualification. The test–retest sample consisted of 36 participants (10 males, 27.8%, and 26 females, 72.2%) with a mean age of 38.1 (SD = 14.3) years.

Measures

Stalking Assessment Indices (SAI)

The original SAI consisted of two indices, first measuring stalking victimisation (SAI-V) then perpetration (SAI-P). Only the acronyms were used, and ‘stalking’ was not mentioned in the survey. Each index had a preamble stating that the respondent would be asked about ‘times when someone has continued to contact or pursue you against your wishes’ (SAI-V); or ‘times that you have continued to contact or pursue another person against their wishes’ (SAI-P). Respondents were directed to answer in relation to the ‘situation that sticks most in their mind’ if they had multiple examples of such situations with different people.

Respondents rated the presence and frequency of 22 behavioural items during the period of unwanted pursuit (answering 0 if they had not experienced unwanted contact/pursuit). The SAI-V and SAI-P measured the same behaviours using modified wording (e.g. SAI-V ‘They broke into my home’ versus SAI-P ‘I broke into their home’). Each item was rated on a 7-point scale indicating how many times the behaviour occurred during the period of unwanted pursuit: ‘never’, ‘once’, ‘twice’, ‘3–5 times’, ‘6–10 times’, ‘11–20 times’ or ‘more than 20 times’.

The behavioural items were followed by supplementary questions that allowed for differentiation of stalking from other forms of harassment or unwanted pursuit. For both indices, the respondent was asked to estimate the duration of the unwanted behaviour, whether it was currently occurring, and the nature of their relationship with the other person involved. The SAI-V then asked about the impact of the behaviour and whether it caused distress or fear (on a 4-point scale from none at all to extremely distressed/fearful). The SAI-P asked for reasons why the person continued their contact even though they were aware it was unwanted but required no judgement about the target’s fear or distress.

The SAI are scored using a combination of behaviour item responses and supplementary information. Each behaviour item response is converted into a numeric score (‘never’ = 0, ‘once’ = 1, ‘twice’ = 2, ‘3–5 times’ = 4, ‘6–10 times’ = 8, ‘11–20 times’ = 15 and ‘more than 20 times’ = 20). Item scores are summed into a total behaviour score for each index, with behaviour scores of six or greater indicating that there have been at least five unwanted intrusions reported. The conduct criteria are met when the duration of behaviours is at least two weeks (14 days), and the index behaviour score is at least six. Responses meeting these criteria on the SAI-P are identified as stalking. Classification as a stalking victim with the SAI-V also required respondent ratings of being ‘quite’, or ‘extremely’ distressed or fearful in addition to meeting conduct criteria.

Buss–Perry Aggression Questionnaire–Short Form (BPAQ-SF)

Aggression was used as a measure of convergent validity for the SAI-P based on research demonstrating high rates of threats and physical violence among those whose stalking attracts criminal justice attention (McEwan, Daffern, MacKenzie, & Ogloff, 2017). Aggression was measured using the Buss–Perry Aggression Questionnaire–Short Form (BPAQ-SF; Bryant & Smith, 2001). The BPAQ-SF assesses four factors: physical aggression, verbal aggression, hostility and anger, with three items per factor. Participants respond to items on a scale from ‘1’ (very unlike me) to ‘5’ (very like me). The BPAQ-SF has demonstrated moderate to good internal consistency (total α = .83 to .86, subscale α from .67 and .84 in student samples; Webster et al., 2014), and good convergent validity with similar measures. Overall internal consistency in the current sample was α = .86.

Perseverative Thinking Questionnaire (PTQ)

The second convergent validity measure assessed rumination, based on research demonstrating increased rumination among those who self-report stalking (Cupach, Spitzberg, Bolingbroke, & Tellitocci, 2011; Spitzberg et al., 2014). The PTQ (Ehring, Zetsche, Weidacker, Wahl, Schönfeld, & Ehlers, 2011) is a 15-item measure that assesses the three key characteristics of general ruminative thinking: that it is repetitive, is unproductive and captures mental capacity. Participants are asked to rate each item on a scale indicating frequency of experience from 0 = never to 4 = almost always (responses were numbered from 1 to 5 in the current research due to the requirements of the questionnaire software). The PTQ demonstrated excellent internal consistency (α = .95) and test–retest reliability (rtt = .69) in the development sample and good convergent validity with other measures of repetitive negative thinking. In the current sample internal consistency was α = .95.

Relational Rumination Questionnaire (RelRQ)

The final convergent validity measure also assessed rumination, but specifically about relationships, based on the assumption that a substantial proportion of participants would report stalking in this context (per Spitzberg & Cupach, 2014). The RelRQ (Senkans, McEwan, Skues, & Ogloff, 2016) consists of 16 items across three scales: rumination about relationship pursuit (RelRQ-RP); rumination about losing a current relationship (relationship uncertainty; RelRQ-RU); and rumination about previous break-ups (RelRQ-BU). Participants respond to items based on how often the statement applies to them from ‘1’ (almost never) to ‘5’ (almost always) with higher scores indicating higher levels of relational rumination. The RelRQ demonstrated good internal consistency (α = .82 to .86) and test–retest reliability (rtt = .71) in the development sample and obtained α = .91 in the current sample.

Procedure

Students self-selected to participate in a study of ‘unwanted contact and pursuit behaviour’ via an online survey platform, with advice against participating if they thought they would be unduly distressed by the topic. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. Participants provided demographic information then completed the construct validity measures in randomised order (with other measures not reported in the current study), before completing the SAI, taking approximately 45 minutes in total. Participation in the test–retest portion of the project was voluntary, and participants were able to respond for up to two weeks after the invitation was issued, with all retesting completed between three and four weeks after Time 1.

Index development

Index development followed the procedure outlined by Diamantopoulos and Winklhofer (2001). While the first two steps in this procedure are theoretical, not empirical, discussing them is necessary to demonstrate valid index development.

Specification of content

Twenty-two behavioural descriptors were developed from a review of items in existing measures of unwanted pursuit and stalking – for example, versions of the Obsessive Relational Intrusion Questionnaire (Spitzberg & Cupach, 2014; Spitzberg et al., 2014); Stalking Behaviour Checklist (Coleman, 1997); Unwanted Pursuit Behaviour Inventory (Langhinrichsen-Rohling, Palarea, Cohen, & Rohlin, 2002); Stalking and Harassment Behaviour Scale (Turmanis & Brown, 2006); and the NVAWS and subsequent modified versions (Amar, 2006; Nobles et al., 2009; Tjaden & Thoennes, 1998). In addition, stalking legislation known to the authors to include specific behaviours was reviewed, along with literature describing stalking behaviour (e.g. McEwan, Daffern, et al., 2017; McEwan et al., 2020; McEwan et al., 2009; Mullen et al., 1999; Pathé & Mullen, 1997; Purcell et al., 2002; Rosenfeld & Harmon, 2002; Sheridan, Davies, & Boon, 2001; Sheridan, Gillett, & Davies, 2002; Sheridan, North, & Scott, 2014). Items were developed or adapted from previous tools to cover the full range of observed categories of unwanted pursuit described by Spitzberg and Cupach (2014; see Table 1 for original SAI items mapped onto their categories). Items were reviewed by psychologist colleagues experienced with either stalkers or stalking victims as a test of coverage of the construct, resulting in adjustment of some item wording.

Table 1.

Original SAI items mapped onto categories of stalking strategies from Spitzberg and Cupach (2014).

| SAI item | Spitzberg and Cupach’s (2014) categories of stalking strategies |

|---|---|

| 1. They made phone calls or sent text messages to me. | Mediated contact/Hyper-intimacy |

| 2. They sent letters, cards or other written material to me. | Mediated contact/Hyper-intimacy |

| 3. They sent emails to me. | Mediated contact/Hyper-intimacy |

| 4. They communicated with me via social networking websites. | Mediated contact/Hyper-intimacy |

| 5. They gave me gifts or other items I didn't ask for. | Mediated contact / Hyper-intimacy/Harassment & intimidation |

| 6. They showed up uninvited somewhere that they knew I would be. | Interactional contact |

| 7. They tried to get information about me from other people (e.g. my family, friends, etc.). | Interactional contact/Proxy pursuit |

| 8. They gave information about me to other people. | Interactional contact/Harassment & intimidation/Proxy pursuit |

| 9. They waited for me outside my home, workplace or school, or places they thought I would be. | Interactional contact/Surveillance |

| 10. They watched me from a distance. | Surveillance |

| 11. They followed me. | Surveillance |

| 12. They drove by my house, work, or places they thought I would be. | Surveillance |

| 13. They posted information about me on the internet (pictures or written information). | Harassment & intimidation |

| 14. They did things to harm my reputation. | Harassment & intimidation |

| 15. They made threats to me or someone close to me. | Coercion and threat/Proxy pursuit |

| 16. They tried to make me have sex with them. | Coercion & Threat/Hyper-intimacy |

| 17. They broke into my home. | Invasion |

| 18. They accessed my computer, phone, or online account(s) without my permission. | Invasion |

| 19. They damaged or vandalised property belonging to me or someone close to me. | Aggression & Violence/Invasion |

| 20. They pushed, shoved, or slapped me or someone close to me. | Aggression & Violence |

| 21. They were physically violent towards me (punched me, kicked me, or something similar) | Aggression & Violence |

| 22. They caused me physical injury | Aggression & Violence |

SAI = Stalking Assessment Indices.

Statistical analyses

Structure of indices and examination of collinearity

Index structure was investigated using the reports of potential victims. Factor Version 10.8.01 was used to conduct principle components analysis (PCA) with promin rotation (Bryant & Yarnold, 1995). Polychoric correlations were calculated given excess kurtosis (105.31, p < .001) and ordinal data (Muthén & Kaplan, 1985). Parallel analysis was used to determine the number of components (Buja & Eyuboglu, 1992). Items loading <.50 were removed unless considered essential to measurement of the stalking construct (per Diamantopoulos & Winklhofer, 2001), while items evidencing multicollinearity were amalgamated.

IBM Statistical Package SPSS Version 24.0 was used to compute descriptive statistics. Multidimensional scaling (MDS) calculated with PROXSCAL (Shye, Elizur, & Hoffman, 1994) was used to visually represent relationships between the behaviours reported by stalking victims: behaviours were coded as present (1) or absent (0). The Lance and Williams measure of association was chosen due to binary data and lack of knowledge about the definite absence of items. Normalised raw stress scores were used to assess goodness of fit. These scores range from 0 (perfect fit) to 1 (no fit; Kruskal & Wish, 1978), with scores below .10 indicating that the model fits the data well (Canter & Heritage, 1990). This procedure is similar to that used in previous research investigating criminal behaviour using MDS (Bennell, Bloomfield, Emeno, & Musolino, 2013).

Validity and reliability

Based on the validated structure of the SAI-V, the SAI-P was refined to the same items and stalkers as those identified using the above scoring instruction. Convergent validity was evaluated using between-group comparisons of stalkers and non-stalkers on each of the convergent validity measures and correlation of SAI-P behaviour scores with total scores of convergent validity measures (Kendall’s τb). Non-normality meant that between-group differences were assessed using Mann–Whitney U with ϴ as the measure of effect size; ϴ > .70 represents a large effect equivalent to d = 1 (Acion, Peterson, Temple, & Arndt, 2006). The concurrent validity of the SAI-V was not assessed in the present study due to concerns about survey length.

Test–retest reliability was examined by comparing the proportion of participants who reported on the same situation and person in Time 1 and Time 2, with κ as a measure of the strength and significance of agreement. Those who did not report on the same situation and person from Time 1 to Time 2 were excluded, then overall agreement was examined to determine whether the same people were classified as stalkers and victims from Time 1 to Time 2, with the statistical significance of agreement assessed using κ.

Results

Structure of the SAI and effects of multicollinearity

The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) test resulting from the PCA showed that the model was very good (.92), but multicollinearity was a concern (determinant of the matrix = .000000016). The three aggression items from Table 1 were multicollinear (ρ ≥ .85) and were collapsed into the item: ‘They were physically violent towards me or someone close to me’ with further descriptive information obtained through supplementary questions (see final SAI at https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/suppl/10.1080/13218719.2020.1787904?scroll=top). The four surveillance and one interactional contact (#6) item in Table 1 were collapsed into two new items due to multicollinearity between the watching and following items (ρ = .75), and between three items measuring versions of loitering (ρ = .73 to .75). The latter were collapsed into They drove by, showed up uninvited, or waited for me at places they thought I would be. The highest item frequency score across collapsed items was used in subsequent analyses.

Three items had component loadings below .50. The first, They tried to make me have sex with them was endorsed by 27% of participants and loaded on Component 2 (.32). Although this was the only item querying sexual behaviour, given the low loading and the close relationship between coercion and aggression in Spitzberg and Cupach’s (2014) categories, this item was removed, and sexual violence was captured descriptively in the supplemental physical violence information. Two harassment and intimidation items also loaded below .50. They posted information about me on the internet was endorsed by 16% of participants and loaded on Component 2 (.38), while They did things to harm my reputation endorsed by 34% and loaded on both Components 1 (.31) and 2 (.46). Given the cross-loading, the latter item was reworded into a more specific format for the final SAI (see https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/suppl/10.1080/13218719.2020.1787904?scroll=top) as it was considered essential to the stalking construct. However, given the changed wording, it was excluded from subsequent analyses. The item describing posting information on the internet was excluded from the PCA due to the low loading but was retained in the final SAI unchanged due to its perceived importance to the construct. It was included in the MDS and all subsequent validity and reliability testing.

The remaining 14 items demonstrated good model fit (KMO test = .89; 95% confidence interval [.88, .90]) and an acceptable determinant of the matrix (0.001) suggesting that multicollinearity was no longer a concern. A parallel analysis recommended two components explaining 55% of the variance. The RMSR = .075 (95% CI [.066, .080]) and WRMR = .075 (95% CI [.067, .008]), which were both acceptable (Yu & Muthén, 2002). The final SAI-V is displayed in Table 2 and in the supplementary materials. The two components were moderately related to each other (r = .56) and were labelled descriptively as (1) intimidation/invasion/aggression and (2) communication/surveillance.

Table 2.

Final SAI-V items and component structure.

| SAI-V itema | Component |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | ||

| 1 | They made phone calls or sent text messages to me (Phone) | .89 | |

| 2 | They gave me gifts or other items I didn't ask for (Gifts) | .84 | |

| 3 | They tried to get information about me from other people (e.g. my family, friends, etc.) (GetInfo) | .73 | |

| 4 | They communicated with me via social networking websites (SocialNetwork) | .71 | |

| 5 | They drove by, showed up uninvited, or waited at places they thought I would be (ShowedUp) | .70 | |

| 6 | They sent emails to me (Emails) | .67 | |

| 7 | They sent letters, cards or other written material to me (Letters) | .66 | |

| 8 | They followed me or watched me from a distance (Followed) | .64 | |

| 9 | They gave information about me to other people (GaveInfo) | .51 | |

| 10 | They damaged or vandalised property belonging to me or someone close to me (DamagedProperty) | .83 | |

| 11 | They were physically violent towards me or someone close to me (Physical) | .84 | |

| 12 | They broke into my home (BrokeIntoHome) | .77 | |

| 13 | They made a threat to harm me or someone close to me (ThreatToHarm) | .73 | |

| 14 | They accessed my computer, phone, or online account(s) without my permission (AccessedTech) | .66 | |

| 15 | The posted information about me on the internet (PostedInfo) | N/A | |

| 16 | They did things to harm my reputation | N/A | |

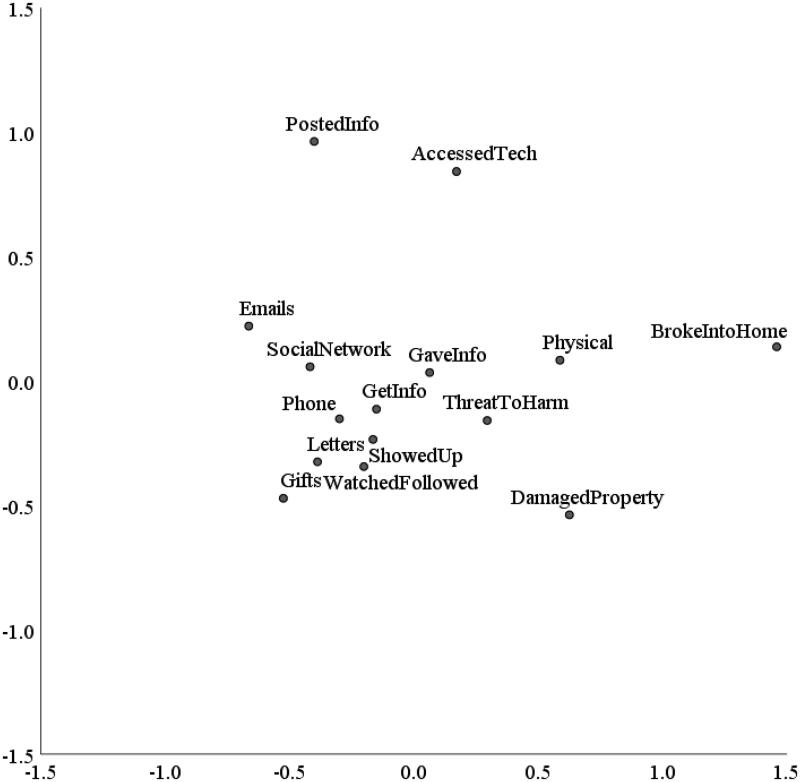

Note: SAI-V = Stalking Assessment Indices–Victimisation. Items 15 and 16 did not load substantially on either component in the principal component analysis (PCA). Both were included in the final SAI given perceived importance to the construct of stalking (Item 16 in a modified form, meaning it was not included in the multidimensional scaling, MDS, shown in Figure 1).

aLabel in brackets corresponds to the item labels used in Figure 1.

Stalking victimisation using the SAI-V

The median SAI-V behaviour score was 14 (range = 0−78; interquartile range, IQR = 19). Seventy percent (n = 171) of the sample met conduct criteria for stalking victimisation (180, 74%, with a behaviour score >5, and 185, 76%, reported duration of at least two weeks). However, 58% (n = 99) of those who met the conduct criteria did not report being ‘quite’ or ‘extremely’ fearful or distressed. Only 2% (n = 4) reported fear/distress without meeting the conduct criteria, three of whom were victims of violence or threats.

Overall, 30% (n = 73) of participants met both the conduct and fear/distress criteria and were classified as stalking victims, of whom 8% (n = 6) reported that they were currently being pursued. Females (n = 66; 35% of female participants) were significantly more likely than males (n = 7; 13% of male participants) to be identified as stalking victims, χ2(N = 244, 1) = 10.93, p = .001, odds ratio (OR) = 3.88. The median duration of stalking victimisation was 18 weeks (range = 2−1872 weeks; IQR = 46 weeks). Most stalking victims reported that the perpetrator was a former romantic partner (n = 47; 64%). Other relationships included casual acquaintances (n = 14; 19%), work colleagues (n = 8; 11%), and other (e.g. professional contacts, strangers; n = 4; 5%). No participants reported stalking by a current partner. The frequency of each of the behaviours experienced by stalking victims and non-victims is presented in Table 3. All bar two (receiving emails and contact via social media) were significantly more common among stalking victims (each having at least twice the odds of occurring during a stalking episode).

Table 3.

Frequency of behaviours reported by victims and non-victims and stalkers and non-stalkers.

| Victims n (%) |

Non-victims |

Stalkers | Non-stalkers |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SAI item | n (%) | χ | OR [95% CI] | n (%) | n (%) | χ | OR [95% CI] | |

| Communication/surveillance | ||||||||

| 1 | 70 (96) | 127 (74) | 15.38*** | 8.08 [2.42, 26.98] | 49 (96) | 45 (23) | 90.18*** | 80.58 [18.85, 344.45] |

| 2 | 44 (60) | 66 (39) | 9.71** | 2.41 [1.38, 4.23] | 13 (26) | 8 (4) | 23.37*** | 7.91 [3.07, 20.40] |

| 3 | 62 (85) | 74 (43) | 35.98*** | 7.39 [3.64, 15.01] | 33 (65) | 21 (11) | 67.82*** | 15.02 [7.23, 31.21] |

| 4 | 47 (64) | 93 (54) | 2.09 | 32 (63) | 32 (17) | 44.43*** | 8.47 [4.28, 16.77] | |

| 5 | 61 (84) | 85 (50) | 24.40*** | 5.14 [2.59, 10.23] | 29 (57) | 14 (7) | 68.39*** | 16.85 [7.75, 36.63] |

| 6 | 34 (47) | 58 (34) | 3.49 | 23 (45) | 13 (7) | 47.20*** | 11.37 [5.17, 25.01] | |

| 7 | 45 (62) | 55 (32) | 18.38*** | 3.39 [1.92, 5.99] | 21 (41) | 8 (4) | 52.82*** | 16.19 [6.57, 39.86] |

| 8 | 52 (71) | 58 (34) | 28.77*** | 4.82 [2.65, 8.77] | 13 (26) | 7 (4) | 25.63*** | 9.09 [3.40, 24.29] |

| 9 | 44 (60) | 51 (30) | 19.95*** | 3.57 [2.02, 6.33] | 11 (22) | 12 (6) | 11.14*** | 4.15 [1.71, 10.07] |

| Intimidation/invasion/aggression | ||||||||

| 10 | 21 (29) | 13 (8) | 19.11*** | 4.91 [2.30, 10.49] | 5 (10) | 1 (0.5) | 14.50*** | 20.87 [2.38, 182.97] |

| 11 | 25 (34) | 25 (15) | 12.10*** | 3.04 [1.60, 5.79] | 5 (10) | 3 (2) | 8.64** | 6.88 [1.59, 29.86] |

| 12 | 9 (12) | 4 (2) | 10.12** | 5.87 [1.75, 19.74] | 2 (4) | 1 (0.5) | 3.84 | |

| 13 | 34 (47) | 22 (13) | 32.88*** | 5.90 [3.11, 11.22] | 5 (10) | 2 (1) | 11.13*** | 10.38 [1.95, 55.20] |

| 14 | 19 (26) | 17 (10) | 10.53*** | 3.19 [1.55, 6.58] | 11 (22) | 6 (3) | 21.21*** | 8.57 [2.99, 24.53] |

| 15 | 17 (23) | 22 (13) | 4.14* | 2.06 [1.00, 1.72] | 1 (2) | 1 (.05) | 1.03 | |

Note: SAI = Stalking Assessment Indices; OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval. A 16th item was included in the final SAI: They spoke or wrote to others about me in ways that harmed my reputation. This is an amended version of a non-loading item (They did things to harm my reputation), and so specific frequency counts were not available.

Behavioural item responses of stalking victims were subject to MDS to investigate which most frequently co-occurred. Figure 1 displays the MDS plot, and a normalised raw stress score of .009 suggested an acceptable fit. The three most common stalking behaviours (see Table 3) were clustered roughly in the centre of the plot, indicating frequent co-occurrence. Broadly, the items measuring communication/surveillance fell on the left side of the plot, while those measuring intimidation/invasion/aggression fell on the right (with the exception of They posted information about me on the internet, which did not load substantially on either factor in the PCA). The former behaviours were generally more closely clustered and centred, suggesting more frequent occurrence and co-occurrence, while the latter behaviours were more widely dispersed, indicating that they did not always co-occur within stalking episodes and that those on the periphery of the plot were less common.

Figure 1.

Multidimensional scaling plot of Stalking Assessment Indices–Victimisation (SAI-V) behavioural items endorsed by victims. Note: Table 2 provides full item names corresponding to the item labels used in this figure.

Internet-mediated behaviours were broadly grouped in the top left quadrant of the plot, though those involving communication were far more common and often co-occurred with other forms of mediated contact such as telephone calls. The other two internet-based behaviours were forms of harassment/intimidation or invasion and were each reported by approximately one quarter of stalking victims. Their position in the plot suggests that they occur together at least some of the time, while the distance from other behaviours indicates they were often reported in the absence of other forms of stalking behaviour.

Stalking perpetration using the SAI-P

The 15-item SAI-V was applied to SAI-P data, and the scoring instructions were followed to identify stalking perpetration. The median SAI-P behaviour score was 0 (range =0−35; IQR = 6). Twenty-six percent of the sample (n = 63) had a behaviour score of at least six, and 29% (n = 70) of participants reported that they had engaged in unwanted pursuit behaviour for at least two weeks.

Overall, 21% (n = 51) of participants were classified as stalkers, with 8% (n = 4) currently pursuing their target. Although males (n = 14; 25% of all males) were slightly more likely than females (n = 42; 20% of all females) to be categorised as stalkers, this difference was not significant, χ2(N = 244, 1) = 0.74, p = .39. The median duration of stalking perpetration was 4.00 weeks (range =2−156 weeks; IQR = 8 weeks). Most reported stalking a former romantic partner (84%), and just over half reported that their behaviour was motivated by their desire to resume a relationship (57%). Others reported that they were casual acquaintances of the victim (14%) or they had met the victim through work (2%). Among this group and the remaining 43% of former intimates, motivations included wanting to start a romantic relationship (8%), to get even or get an apology (24%), or to get back at the victim after a break-up (14%). None reported stalking a current partner. The frequency of each of the behaviours reported by stalking perpetrators and non-perpetrators is presented in Table 3.

Convergent validity of the SAI-P and test–retest reliability

Table 4 shows differences between stalkers and non-stalkers on convergent validity measures. BPAQ-SF and RelRQ total scores generally showed positive correlations with stalking perpetration, though these were not always significant, and were smaller or non-existent for women. However, significant differences were observed between stalkers and non-stalkers in both general aggression and relationship rumination, with large effect sizes among males and small effect sizes among females. Notably, ruminating about relationship breakdown was most closely related to stalking perpetration, with a stronger association among males. General rumination did not differentiate between stalkers and non-stalkers in the whole group, or among women, but did so with a moderate effect size among men.

Table 4.

Stalking Assessment Indices - Perpetration relationship with concurrent validity measures.

| N | Stalkers |

Non-stalkers |

U | ϴ | τ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Med (IQR) | N | Med (IQR) | |||||

| Total | 51 | 193 | ||||||

| BPAQ-SF | 240 | 28.00 (10.50) | 24.00 (10.00) | 3511.00** | .63 | .13** | ||

| PTQ | 244 | 43.00 (15.00) | 43.00 (15.00) | 4862.50 | .04 | |||

| RelRQ | 241 | 35.50 (11.25) | 26.00 (15.00) | 3009.50*** | .68 | .18*** | ||

| RelRQ-RP | 242 | 10.00 (7.25) | 8.00 (8.00) | 3548.00** | .63 | .11* | ||

| RelRQ-RU | 242 | 13.00 (11.00) | 10.00 (6.00) | 3670.00** | .62 | .14** | ||

| RelRQ-BU | 241 | 10.00 (7.00) | 6.00 (6.00) | 2951.00*** | .69 | .18*** | ||

| Males | 14 | 42 | ||||||

| BPAQ-SF | 54 | 30.00 (8.00) | 25.00 (8.00) | 140.00** | .75 | .15 | ||

| PTQ | 56 | 49.50 (14.00) | 43.00 (14.25) | 189.00* | .69 | .13 | ||

| RelRQ | 55 | 42.50 (12.50) | 25.00 (16.50) | 92.00*** | .84 | .34*** | ||

| RelRQ-RP | 55 | 13.00 (4.25) | 7.00 (7.00) | 136.50** | .76 | .29** | ||

| RelRQ-RU | 55 | 15.00 (7.25) | 9.00 (6.00) | 122.00*** | .78 | .26* | ||

| RelRQ-BU | 55 | 13.00 (8.25) | 6.00 (6.00) | 112.00*** | .80 | .39*** | ||

| Females | 42 | 146 | ||||||

| BPAQ-SF | 186 | 26.00 (10.50) | 23.00 (10.75) | 2190.50ǂ | .59 | .13* | ||

| PTQ | 188 | 40.00 (10.00) | 43.00 (15.00) | 2459.50 | .01 | |||

| RelRQ | 186 | 33.50 (10.75) | 27.00 (15.00) | 2014.00* | .62 | .12* | ||

| RelRQ-RP | 188 | 9.50 (7.00) | 8.00 (8.00) | 2295.00 | .05 | |||

| RelRQ-RU | 188 | 12.00 (12.50) | 10.00 (7.00) | 2382.50 | .12* | |||

| RelRQ-BU | 186 | 9.00 (7.75) | 6.00 (6.00) | 1915.00** | .65 | .10 | ||

Note: BPAQ-SF = Buss Perry Aggression Questionnaire Short Form; PTQ = Perseverative Thinking Questionnaire; RelRQ = Relational Rumination Questionnaire; RelRQ-RP = Relational Rumination Questionnaire–Relationship Pursuit; RelRQ-BU = Relational Rumination Questionnaire–Break-Up; RelRQ-RU = Relational Rumination Questionnaire–Relationship Uncertainty; IQR = interquartile range.

ǂp < .10. *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Thirty-six participants completed the SAI twice. Of these, 94% (n = 34) reported on the same cases at Time 1 and Time 2 (κ = .97, p < .001). SAI-V behaviour scores were significantly correlated between Time 1 and Time 2 (τ = .64, p < .001). The SAI-V classified 82% (n = 28) of participants consistently across time (κ = .62, p < .001). Inconsistent classification was the result of reductions in the level of reported fear between Time 1 and Time 2. SAI-P behaviour scores at Time 1 and Time 2 were similarly significantly correlated (τ = .68, p < .001), while the SAI-P classified 91% (n = 31) of participants consistently across time (κ = .68, p < .001). Inconsistent classification was due to changes in reported duration of unwanted pursuit, with two thirds of the cases reporting reduced duration and one third involving ongoing stalking episodes that crossed the duration threshold between assessments.

Discussion

The aim of this research was to develop a valid, reliable and time-efficient stalking measure that could be used to assess both victimisation and perpetration across research settings. In defining the construct of stalking we followed Fox et al.’s (2011) recommendation that rigorous measures should ascertain the presence of stalking from the combination of a pattern of conduct (measured on the SAI using the conduct criteria and duration of unwanted contact) and victim impact and/or perpetrator intent (impact assessed directly in the SAI-V and impact and intent via the proxy of the conduct criteria on the SAI-P). In doing so, the SAI addresses the issue of measuring ‘episodes’ of stalking rather than discrete acts (Nobles et al., 2009). The use of an evidence-based proxy for victim impact may be helpful as it reduces dependence on potentially unreliable self-reports of the perpetrator’s negative intent or perceived victim impact. However, it may also introduce other forms of error until tested further against reported victim impact, particularly among male victims of female stalkers. The SAI also addresses many of Fox and colleagues’ other recommendations for measurement of stalking, discussed below.

Measurement format and content

The SAI use multiple behavioural descriptors, allowing for more sophisticated analysis of which stalking behaviours are related to victim and perpetrator outcomes. We also addressed Fox et al.’s (2011) recommendation of reflecting previous research by conducting a census of existing stalking measures when developing items. We were particularly careful to ensure that the SAI included at least one item from every category of unwanted pursuit that Spitzberg and Cupach (2014) had observed throughout their years of research describing stalking behaviour. Indeed, the full breadth of pursuit categories remained after the 22 original behavioural descriptors were reduced to 16 items, giving us confidence that the final SAI provides a comprehensive measure of the stalking construct and includes items that have been used in previous measures of stalking.

Subjecting the SAI-V behavioural items to MDS addressed Fox et al.’s (2011) recommendation to identify ‘core’ stalking behaviours that should be measured across samples. In our Australian university sample, the three ‘core’ stalking items were telephone calls, showing up at locations where the victim was likely to be, and getting information about the victim from other people. Telephone calls being the most common stalking behaviour is consistent with findings from epidemiological surveys of stalking victimisation (Baum, Catalano, Rand, & Rose, 2009; Purcell et al., 2002), providing some measure of external consistency. Loitering and getting information about the victim from others were more unexpected core behaviours. It is possible that the university sample may have led to over-representation of these behaviours due to the predominantly relationship pursuit motives for stalking in this group and structure of university campus life (Ravensberg & Miller, 2003). It would be interesting to see whether the same core stalking behaviours were endorsed by stalking victims recruited in non-university settings.

In the same vein, it would be interesting to observe whether stalking behaviours reported by both victims and perpetrators are similar in samples reporting a wider variety of stalking contexts. Almost two thirds of victims and four of every five perpetrators in this sample reported stalking after relationship breakdown. This substantially over-estimates the prevalence of this context for stalking (which accounts for just under 50% of stalking cases in meta-analyses; Spitzberg & Cupach, 2014). Whether stalking due to grievances or grudges unrelated to intimate relationships, or stalking behaviour that emerges secondary to a serious mental illness, would result in similar SAI response patterns is unclear. Research examining patterns of behaviour by forensically involved stalkers suggests that while there are some contextual differences in the frequency and tone of different behaviours (e.g. former partners are generally more threatening and aggressive, and more insistent than other stalkers; Mohandie, Meloy, Green McGowan, & Williams, 2006), the majority of stalking behaviours are present regardless of context (McEwan & Davis, 2020). However, this awaits further testing in larger, more representative samples.

Measurement validity and reliability

This study provided evidence to support the validity and reliability of the SAI as measures of stalking victimisation and perpetration. The SAI-V appears to have a two-component structure that is consistent with previous descriptions of stalking. One component captures Spitzberg and Cupach’s (2014) categories of surveillance and mediated and interactional contact (the latter potentially taking the form of ‘hyper-intimacy’, where normal romantic courtship behaviours are taken to an extreme). The other captures their categories of harassment and intimidation, coercion and threat, invasion, and aggression and violence. Studies of stalkers suggest that the behaviour occurs on a continuum from less severe but more common (hyper-intimacy, mediated and direct contact, and surveillance), to more severe but less common (harassment and intimidation, invasion, and aggression; see Thompson & Leclerc, 2014). This is consistent with the frequency of behaviours that were reported in the current study among both victims and stalkers identified using the SAI.

The broader construct validity of the SAI can be assessed through comparison of identified stalking prevalence with that reported in previous studies (noting the inherent limitations associated with variation in the definition of stalking used across samples). The lifetime incidence of stalking victimisation identified by the SAI in the current small sample fell in the middle of estimates reported in previous college samples (ranging from 7% to 56%; Spitzberg & Cupach, 2014). It was higher than Spitzberg and Cupach’s (2014) meta-analytic unadjusted mean prevalence of stalking victimisation of 20% across 70 college samples, though within one standard deviation of the mean. Higher prevalence may be attributable to the preponderance of female participants in the current study, given that women are more likely to report stalking victimisation overall (Spitzberg & Cupach, 2014). The lifetime incidence of stalking perpetration in this study (21%) was similar to Spitzberg, Cupach, and Ciceraro’s (2010) meta-analysis of 19 studies of stalking perpetration (26%). The similar rates of perpetration across men and women in the current study was somewhat unexpected (and contrary to Spitzberg et al., 2010) but have also been observed in past studies reporting stalking perpetration in college-based samples (see Spitzberg & Cupach, 2014).

Further evidence of the validity of the SAI-P comes from the convergent validity analyses, where stalkers were significantly more likely to endorse psychological and behavioural characteristics that are theoretically associated with stalking behaviour. Consistent with relational goal pursuit theory (Spitzberg & Cupach, 2000/2014), self-reported stalkers endorsed more rumination about relationships, and particularly about relationship breakdown (perhaps unsurprisingly given 84% of the sample were stalking former partners), with the difference for male stalkers achieving a large effect size. Male stalkers also reported more general rumination that was not specific to relationships, though the same was not true of female stalkers. Consistent with information processing theory (Birch et al., 2018), stalkers were more likely to report greater levels of lifetime physical aggression, verbal aggression, hostility and anger than non-stalkers. This relationship was present for both males and females, though again, stronger among males. Were these gender differences replicated, it would suggest that current theoretical approaches more closely reflect male pathways to stalking behaviour, and further theorising may be required for female stalkers. We were unable to assess the SAI-V’s convergent validity, but future research could examine characteristics such as endorsement of lifestyle changes and traumatic symptomatology.

This study is the first to report on the test–retest reliability of a stalking measure. The SAI demonstrated good short-term test–retest reliability, with the vast majority of respondents being consistently classified as stalkers or victims from Time 1 to Time 2. Some inconsistency in perpetrator classification was due to the duration criterion used to define stalking in the SAI-P, with sufficient time passing between Times 1 and 2 for a continued pattern of behaviour to cross the threshold from harassment to be identified as stalking. Inconsistency in victimisation classification was due to changes in the level of distress or fear, rather than in stalking behaviour. It may be that targets’ perceptions of the unwanted pursuit vary depending on how recently it occurred, changes in the nature of the behaviour, or other factors that lead to increased or decreased resilience on particular days (Sato Mumm & Cupach, 2010). If victim impact is changeable over time (as might be expected given the duration of some stalking episodes), this raises questions about the reliability of using impact as part of the definition of stalking for research purposes, given that ascertainment may vary over time. It would be beneficial to test the reliability of victim classification over a longer period of time, using more time points and with a more diverse sample, to determine whether the current findings can be replicated and whether more thought needs to be given to how victim impact is defined and measured.

Strengths and limitations of the SAI

The SAI appear to provide a valid, reliable and time-efficient way of ascertaining both stalking victimisation and perpetration. They provide a transparent definition of stalking that is consistent with prior research and can be adjusted by future researchers to meet their needs (e.g. adjusting the conduct criteria to be consistent with a local legislated definition). The SAI can also be used without the stalking threshold as a broader measure of harassment. The format of the SAI makes it relatively easily adapted in future research in cross-cultural settings. The present items were drawn from the existing literature on stalking, which is largely restricted to the English-speaking industrialised world and Western Europe. With a few notable exceptions (Chan & Sheridan, 2017, 2020; Chan, Sheridan, & Adjorlolo, 2020; Jagessar & Sheridan, 2004; Ndubueze, Hussein, & Sarki, 2017), recognition of stalking and research into the phenomenon are only just beginning outside of these areas. It is our hope that future translations of the SAI might provide a starting point for conducting research into stalking in other cultures. The structure of the indices is particularly suited to this purpose, as additional items could be incorporated through future validation studies using similar analytic approach to the current study. This would allow researchers to address questions about similarities and differences in stalking behaviour in collective cultures and/or cultures with more overtly patriarchal social structures.

One of our motivations for developing the SAI was to enable consistent measurement of stalking perpetration across research settings. This is essential if we are to begin to compare findings from general community and college samples with those collected in clinical/forensic settings. At present, these two literatures are so distinct that it is impossible to know whether findings from one can be generalised to the other. However, if those identified as stalkers across different research settings are shown to be comparable, the results of experimental research in community or college samples may be generalised into assessment or treatment practice with stalkers in forensic settings. The SAI provides some useful metrics that could be directly compared across research settings, such as the frequency score, duration and nature of the stalking behaviours endorsed.

While the SAI appears to have promise as a measure of stalking, it also has some important limitations. In its current form, the SAI can only measure a single stalking episode. Using the lifetime timeframe, the respondent is directed to report the episode that ‘sticks most in your mind’ in the hope of reducing memory effects. This means that measuring repeat victimisation across the lifetime would require multiple administrations of the SAI, focusing on each different episode of stalking. The SAI’s focus on a single episode and prioritisation of time efficiency also means that it does not provide detailed information about the overall pattern of a stalking episode (e.g. changes in the frequency of stalking behaviour across the episode). The SAI also relies on the respondent’s view of when the unwanted pursuit commenced and ended, which limits the detail that can be ascertained about desistence and recurrence of stalking. However, the SAI is primarily intended as a means of categorisation to allow for more detailed research into other aspects of either perpetration or victimisation. Like Fox et al. (2011), we suggest that more fine-grained analysis of the topography of stalking episodes should make use of qualitative methodologies and longitudinal research designs (e.g. Sato Mumm & Cupach, 2010).

Study limitations

This study again estimated lifetime incidence of stalking, an approach criticised by Fox et al. (2011). This choice was made to maximise stalking incidence for validation purposes, though the SAI could easily be made relevant to specific timeframes by simply adjusting the preamble from ‘have you ever . . . ’ to ‘in the past year . . . ’ or ‘at the end of your last relationship . . . ’, or another timeframe.

The sample itself carries with it a number of limitations, including its moderate size and selective nature. While the limited convenience sample provided sufficient power for the statistical analyses undertaken, it is recommended that the study methodology is replicated in a larger and more representative community sample. The use of a university sample may also limit generalisability, as Fox et al. (2011) observed. Some previous authors have suggested that college samples may be biased towards higher rates of stalking victimisation (Fisher, Cullen, & Turner, 2002; Tjaden & Thoennes, 1998). However, Brady, Nobles, and Bouffard (2017) specifically tested this hypothesis and found that differences in the prevalence of stalking victimisation between college and community samples are largely due to selective age effects, given the restricted age of most samples recruited from US colleges. The average age of participants in the current sample was 35 years and ranged from 18 to 74 years. This age distribution is unusual when contrasted to that of college samples from the United States, but has been observed in previous research using the same recruitment technique at the same university and likely reflects the substantial number of mature-aged students returning to study at this institution (Senkans, McEwan, & Ogloff, 2017; Simmons, McEwan, & Purcell, 2019). While a representative community sample would have been ideal for this research, the wider age range within this study’s student sample may mean the rate and nature of victimisation reported is somewhat more generalisable to the wider population than would ordinarily be the case.

The other significant shortcoming of this sample is the bias towards female respondents. As previously observed, this may have inflated the rate of stalking victimisation given recognised gender differences in this regard. Interestingly, rates of stalking perpetration were similar among males and females in this sample, perhaps suggesting that the bias towards male perpetration observed in forensic samples reflects their more frequent aggression and reporting biases rather than a true gender bias in perpetration behaviour. Research is currently underway testing the performance of the SAI in a larger sample of males (recruited from the same university setting) and in a sample of offenders convicted of both stalking and non-stalking offences.

Future directions and conclusion

The SAI provide one approach to a consistent definition of stalking that produces valid and reliable measurement. If the SAI are adopted by other researchers and can be shown to be reliable and valid in other settings, they could contribute to greater conceptual clarity about the phenomenon of stalking and improved collection of consistent information about stalking episodes. Use and testing across different samples would also identify areas where the SAI do not currently provide sufficient coverage of the construct and potentially need to be expanded or modified. Adoption of the SAI, or a similarly constructed and tested instrument, will also facilitate more widespread evaluation of theoretical accounts of stalking, which has been sorely lacking in the field to date and is required to help to develop prevention strategies (Johnson & Thompson, 2016). We hope that by developing and testing the SAI we can contribute to the growth of a richer body of knowledge about stalking, which in turn can improve policy and practice to prevent this common and damaging behaviour.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Ethical standards

Declaration of conflicts of interest

Troy McEwan has declared no conflicts of interest

Melanie Simmons has declared no conflicts of interest

Taryn Clothier has declared no conflicts of interest

Svenja Senkans has declared no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with and approval of the University human research ethics committee] and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individul participants included in the study.

References

- Acion, L., Peterson, J.J., Temple, S., & Arndt, S. (2006). Probabilistic index: an intuitive non-parametric approach to measuring the size of treatment effects. Statistics in Medicine, 25(4), 591–602. doi: 10.1002/sim.2256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amar, A.F. (2006). College women's experience of stalking: Mental health symptoms and changes in routines. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 20(3), 108–116. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2005.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (1996). Women's safety, Australia, 1996. Retrieved from https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/4128.0/

- Backes, B.L., Fedina, L., & Holmes, J.L. (2020). The criminal justice system response to intimate partner stalking: A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative research. Journal of Family Violence, advance online publication. doi: 10.1007/s10896-020-00139-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baum, K., Catalano, S., Rand, M., & Rose, K. (2009). Stalking victimization in the United States. U.S. Department of Justice. Retrieved from https://www.justice.gov/sites/default/files/ovw/legacy/2012/08/15/bjs-stalking-rpt.pdf

- Bendlin, M., & Sheridan, L. (2019). Risk factors for severe violence in intimate partner stalking situations: an analysis of police records. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, advance online publication. doi: 10.1177/0886260519847776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennell, C., Bloomfield, S., Emeno, K., & Musolino, E. (2013). Classifying serial sexual murder/murderers: An attempt to validate Keppel and Walter’s (1999) model. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 40(1), 5–25. doi: 10.1177/0093854812460489 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Birch, P., Ireland, J.L., Ninaus, N. (2018). Treating stalking behaviour. In Ireland J. L., Birch P., & Ireland C. A. (Eds.), The Routledge international handbook of human aggression: current issues and perspectives. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bjerregaard, B. (2000). An empirical study of stalking victimization. Violence and Victims, 15(4), 389–406. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.15.4.389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollen, K., & Lennox, R. (1991). Conventional wisdom on measurement: A structural equation perspective. Psychological Bulletin, 110(2), 305–314. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.110.2.305 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brady, P.Q., Nobles, M.R., & Bouffard, L.A. (2017). Are college students really at a higher risk for stalking?: Exploring the generalizability of student samples in victimization research. Journal of Criminal Justice, 52, 12–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2017.07.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brownhalls, J., Duffy, A., Eriksson, L., & Barlow, F.K. (2019). Reintroducing rationalization: a study of relational goal pursuit theory of intimate partner obsessive relational intrusion. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, advance online publication. doi: 10.1177/0886260518822339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant, F.B., & Smith, B.D. (2001). Refining the architecture of aggression: A measurement model for the Buss–Perry Aggression Questionnaire. Journal of Research in Personality, 35(2), 138–167. doi: 10.1006/jrpe.2000.2302 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant, F.B., & Yarnold, P.R. (1995). Principal-components analysis and exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis. In Grimm L. G. & Yarnold P. R. (Eds.), Reading and understanding multivariate statistics (p. 99–136). American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]