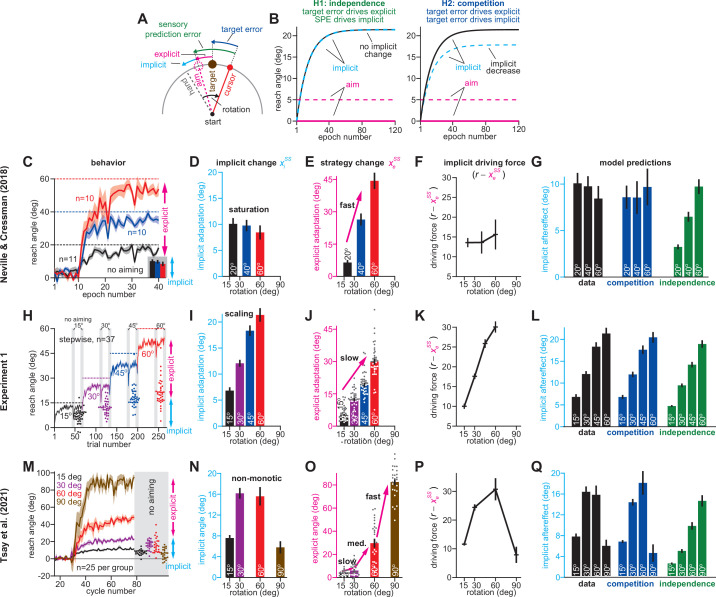

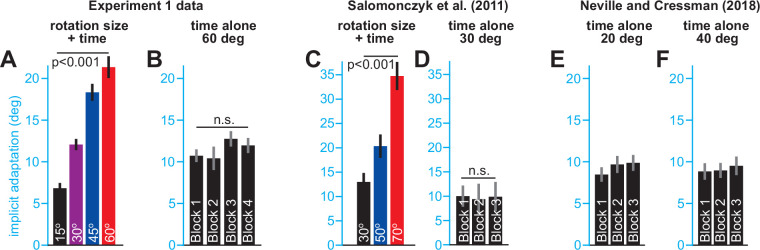

Figure 1. Total implicit learning is shaped by competition with explicit strategy.

(A). Schematic of visuomotor rotation. Participants move from start to target. Hand path is composed of explicit (aim) and implicit corrections. Cursor path is perturbed by rotation. We explored two hypotheses: prediction error (H1, aim vs. cursor) vs. target error (H2, target vs. cursor) drives implicit learning. (B) Prediction error hypothesis predicts that enhancing aiming (dashed magenta) will not change implicit learning (black vs. dashed cyan) according to the independence equation. Target error hypothesis predicts that enhancing aiming (dashed magenta) will decrease implicit adaptation (black vs. dashed cyan). (C) Data reported by Neville and Cressman, 2018. Participants were exposed to either a 20°, 40°, or 60° rotation. Learning curves are shown. The “no aiming” inset shows implicit learning measured via exclusion trials at the end of adaptation. Explicit strategy was calculated as the voluntary reduction in reach angle during the no aiming period. (D) Implicit learning measured during no aiming period in Neville and Cressman yielded a ‘saturation’ phenotype. (E) Explicit strategies calculated in Neville & Cressman dataset by subtracting exclusion trial reach angles from the total adapted reach angle. (F) The implicit learning driving force in the competition theory: difference between rotation and explicit learning in Neville and Cressman. (G) Implicit learning predicted by the competition and independence models in Neville and Cressman. Models were fit assuming that the implicit learning gain was identical across rotation sizes. (H) Experiment 1. Subjects in the stepwise group (n = 37) experienced a 60° rotation gradually in four steps: 15°, 30°, 45°, and 60°. Implicit learning was measured via exclusion trials (points) twice in each rotation period (gray ‘no aiming’). (I) Total implicit learning calculated during each rotation period in the stepwise group yielded a ‘scaling’ phenotype. (J) Explicit strategies were calculated in the stepwise group by subtracting exclusion trial reach angles from the total adapted reach angle. (K) The implicit learning driving force in the competition theory: difference between rotation and explicit learning in the stepwise group. (L) Implicit learning predicted by the competition and independence models in the stepwise group. Models were fit assuming that implicit learning gain was constant across rotation size. (M) Data reported by Tsay et al., 2021a. Participants were exposed to either a 15°, 30°, 60°, or 90° rotation. Learning curves are shown. The “no aiming” inset shows implicit learning measured via exclusion trials at the end of adaptation. (N) Implicit learning measured during no aiming period in Tsay et al. yielded a ‘non-monotonic’ phenotype. (O) Explicit strategies calculated in Tsay et al. dataset by subtracting exclusion trial reach angles from the total adapted reach angle. (P) Implicit learning driving force in the competition theory: difference between rotation and explicit learning in Tsay et al. (Q) Total implicit learning predicted by the competition and independence models in Tsay et al. Models were fit assuming that the implicit learning gain was identical across rotation sizes. Error bars show mean ± SEM, except in the independence predictions in G, L, and Q; independence predictions show mean and standard deviation across 10,000 bootstrapped samples. Points in H, J, M, and O show individual participants.