Figure 1.

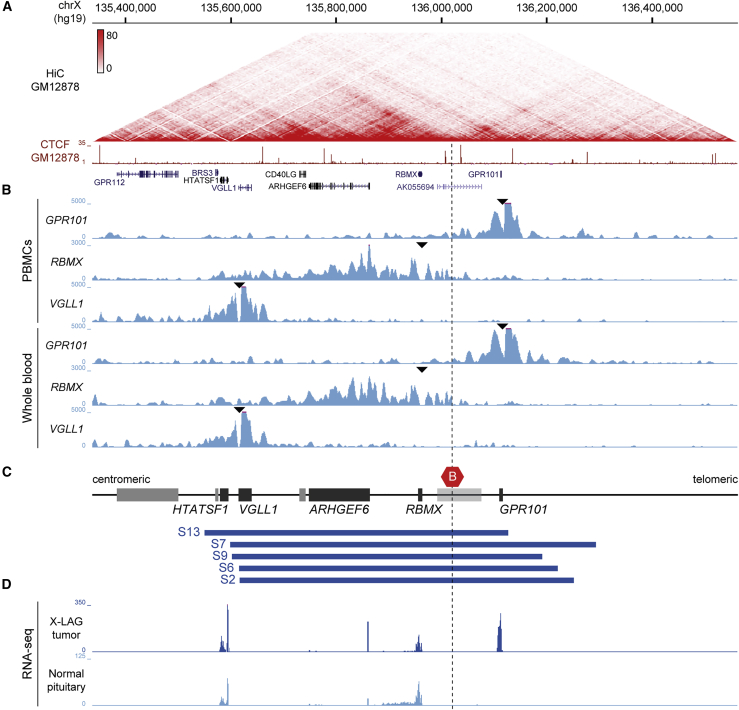

Chromatin organization at the X-LAG locus

(A) Hi-C data from GM12878 lymphoblastoid cells, visualized in the UCSC genome browser at 5 kb resolution (hg19, chrX:135,336,766–136,561,684), showing TAD organization at the X-LAG locus. The ChIP-seq signal for the transcriptional regulator CTCF from GM12878 lymphoblastoid cells and gene annotation are shown underneath. Frequent chromatin interactions within TADs and prominent loop interactions are delimited by CTCF binding sites.

(B) 4C-seq interaction profiles of control samples with viewpoints (black triangles) in the promoters of GPR101, RBMX, and VGLL1 in samples of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs, upper three tracks) and nucleated blood cells from peripheral blood samples (lower three tracks). Prominent chromatin interactions from each promoter are confined to the respective TADs, recapitulating the TAD organization observed by Hi-C.

(C) Schematic representation of the X-LAG locus and genomic positions of five different tandem duplications from subjects with X-LAG (blue boxes). All duplications involve the invariant TAD border (red hexagon) that under normal conditions separates GPR101 and genomic sequences located centromerically, including RBMX and ARHGEF6. For the sake of visualization, genes that were studied in the current experiments are indicated as black boxes while genes not of relevance to the current work are shown in gray boxes. Note that the gene body of the pseudogene AK055694 (light gray box) overlaps with the TAD border but its putative promoter is located centromeric to the TAD border.

(D) Mean RNA expression levels in four X-LAG tumors and three normal pituitaries show consistent upregulation of GPR101 in individuals with X-LAG duplications.

All panels are aligned to have the same start and end genomic coordinates.