Abstract

Stable closure of skin wounds with engineered skin substitutes (ESS) requires indefinite mitotic capacity to generate the epidermis. To evaluate whether keratinocytes in ESS exhibit the stem cell phenotype of label retention, ESS (n = 6–9/group) were pulsed with 5-bromo-2’-deoxyuridine (BrdU) in vitro, and after grafting to athymic mice (n = 3–6/group). Pulse and immediate chase in vitro labeled virtually all basal keratinocytes at day 8, with label uptake decreasing until day 22. Label retention in serial chase decreased more rapidly from day 8 to day 22, with a reorganization of BrdU-positive cells into clusters. Similarly, serial chase of labeled basal keratinocytes in vivo decreased sharply from day 20 to day 48 after grafting. Label uptake was assessed by immediate chases of basal keratinocytes, and decreased gradually to day 126, while total labeled cells remained relatively unchanged. These results demonstrate differential rates of label uptake and retention in basal keratinocytes of ESS in vitro and in vivo, and a proliferative phenotype with potential for long-term replication in the absence of hair follicles. Regulation of a proliferative phenotype in keratinocytes of ESS may improve the biological homology of tissue-engineered skin to natural skin, and contribute to more rapid and stable wound healing.

Somatic stem cells in human epidermis provide essential functions of protection from the terrestrial environment, and regulation of fluid loss from the body. The fundamental property of physical protection results from epidermal barrier which forms by a highly regulated balance between proliferation of basal keratinocytes, and differentiation of suprabasal keratinocytes to form the stratum corneum. Keratinocyte stem cells have been traced to the “bulge” area of the hair follicle which contributes to the interfollicular epidermis during wound healing, and to the base of the follicle which generates hair.1–4 Replication rates of human epidermal keratinocytes have been estimated by several approaches, including labeling index, mitotic index, cell cycle time, duration of DNA synthesis, and epidermal transit time.5,6 Epidermal stem cells are understood to endure for the lives of healthy individuals.

Several models of engineered human skin have been described for studies of cutaneous biology and disease, in vitro toxicology, and transplantation for treatment of skin wounds including burns, chronic wounds, and congenital lesions.7–10 For therapeutic applications, reestablishment of stable epidermis requires the regeneration of epidermal barrier to close the wound, and restoration of as many as possible of the cutaneous appendages, including the hair and glands.11,12 Most models of engineered skin are derived from cultured skin cells, which can be propagated to large populations in culture media containing growth factors and hormones that stimulate rapid mitosis by duplication of a wound healing physiology in vitro. Propagation of keratinocytes often depends on peptide growth factors that act through the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) to stimulate cell division at subconfluent densities through 20 or more population doublings.13 Propagation is commonly followed by stratification of postconfluent keratinocytes to generate an analog of stratum corneum, during which time the high-density populations produce autocrine and paracrine mitogens that reduce the requirements for exogenous growth factors.14–17 Not surprisingly, these conditions do not restore epidermal adnexae, which form during fetal development, and are not regenerated during wound healing in humans.18–20

Engineered skin substitutes (ESS; formerly called cultured skin substitutes)21–24 have been designed and tested in pre-clinical studies, and shown to form partial skin barrier and basement membrane, and to release high levels of potent angiogenic factors. These factors include, but are not limited to, vascular endothelial growth factor, basic fibroblast growth factor, and transforming growth factor β−1.25–27 Consequently, epidermal growth factor (EGF), which is included in medium for keratinocyte propagation, is removed from media during stratification and differentiation of ESS.28 If prepared with autologous keratinocytes and fibroblasts from patients with extensive, full-thickness burns, ESS have been shown to close excised burn wounds indefinitely.22,29 However, the healed skin is afollicular, and, therefore, does not contain the principal sources of keratinocyte stem cells in the hair follicle. This anatomic deficiency raises the biological question: “where is the location of the progenitor cells of the repaired epidermis?” The present study provides an initial investigation of this question by performing pulse-chase experiments with incorporation of 5-bromo-2’-deoxyuridine (BrdU) into ESS in vitro, and after grafting to athymic mice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Human skin cells were isolated from healthy adult donors undergoing breast reduction or abdominoplasty. Tissue was obtained under a protocol approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Cincinnati. Cultures of human keratinocytes (hK) and fibroblasts (hF) were propagated in primary culture, and cryopreserved as previously described.30

Preparation of ESS

ESS were prepared as previously described.30 Briefly, keratinocytes were grown in selective culture in modified medium MCDB15331 supplemented with 1.0 ng/mL EGF, 5.0 μg/mL insulin, 0.5 μg/mL hydrocortisone, and 0.2%v/v bovine pituitary extract. Fibroblasts were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 4% fetal bovine serum, 10 ng/mL EGF, 5.0 μg/mL insulin, 0.5 μg/mL hydrocortisone, and 0.1 mM ascorbic acid 2-phosphate. Media were removed and replaced at 2-day intervals. Cells were harvested and inoculated on sequential days onto collagen-chondroitin-sulfate matrices32,33 hydrated in HEPES-buffered saline solution, followed by supplemented medium UCMC160, which consists of DMEM supplemented with 10 ng/mL EGF, 10 nM progesterone, 5.0 μg/mL insulin, 0.5 μg/mL hydrocortisone, 2.0 μg/nL linoleic acid, 1 mM strontium chloride, 20 pM triiodothyro-nine, 0.1 mM ascorbate-2-phosphate, and standard antimicrobial agents.34 Fibroblasts were inoculated at 5e5/cm2, and keratinocytes at 1e6/cm2. After inoculation, ESS were incubated at the air–liquid interface for 3 days in medium UCMC160, and then in medium UCMC16135 until assay or grafting. UCMC161 is identical to UCMC160, except that the EGF and progesterone are removed.

Grafting of ESS to athymic mice

All animal studies were performed under a protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Cincinnati. On incubation day 15, ESS were cut to 2 cm × 2 cm squares, and grafted to full-thickness excised wounds on the right flanks of 20 athymic nu/nu mice.23,30,36 Dressings and sutures were removed at postoperative day (POD) 14.

Labeling with BrdU

For in vitro samples, ESS were incubated for 3 days in medium UCMC160, and 5, 12, or 19 days medium UCMC161.37,38 On incubation days, 5–7, 12–14, or 19–21, 65 μM BrdU was added to the incubation medium. After 1, 8, or 15 days, samples were collected and prepared for cryomicrotomy, and detection by immunohistochemistry with anti-BrdU antibodies labeled with fluorescein (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA), and immunofluorescence microscopy.

Epidermal keratinocytes were labeled with rabbit anti-human pan-cytokeratin antibodies followed by fluorescent localization using Alexafluor 594 conjugated to goat anti-rabbit antibodies (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). For in vivo samples, on POD 17–19, mice received twice-daily intraperitoneal and subcutaneous injections (50 mg/kg) of BrdU. Mice were euthanized at 20, 27, 34, 48, 83, and 126 days after grafting (n = 3 per time point). At POD 45–47, 79–82, or 123–125, mice (n = 1–3 per time point) with grafted ESS which were not pulsed previously, were pulsed with BrdU by the same protocol, and euthanized at POD 48, 83, or 126. Biopsies were collected for histology and immunohistochemistry. BrdU in healed skin was detected with anti-BrdU antibodies labeled with horseradish peroxidase, and detected with diaminobenzidine (Abcam, Cambridge, MA). To confirm engraftment, hK in grafted ESS were identified by immunohistochemistry using a fluorescein-labeled anti-human leukocyte antigens-ABC (HLA-ABC) antibody (Accurate Chemical and Scientific Corp., Westbury, NY). Samples without a positive signal for (HLA-ABC) were not analyzed further.

Sampling plan, data collection, and statistical analysis

For in vitro samples, three samples from duplicate ESS were scored (13–18 fields per sample) for BrdU-positive basal keratinocytes. For in vivo samples, animals were euthanized, and each ESS graft was divided into four parts: two each for paraffin embedment and for cryomicrotomy. Each paraffin biopsy had three noncontiguous sections mounted on standard microscope slides, and reacted to label the incorporated BrdU. Three images per section were collected at 20× magnification (600–750 μm/field), and scored for BrdU-positive basal and suprabasal keratinocytes. In total, 18–54 values (1–3 animals × 2 biopsies/animal × 3 sections/biopsy × 3 fields/section) per condition were collected for scoring of BrdU incorporation. Microscopic fields with values of 0 were assigned a value of 0.001 to allow computation of the rates of label loss as logarithmic functions.

Scoring of HLA-ABC-positive keratinocytes was performed on cryotome sections as previously described, and each animal was scored as positive before inclusion of BrdU data in quantification.

Rates of loss of BrdU-positive nuclei in basal keratinocytes were determined by regression analysis using the formula

| (1) |

where m is the slope of exponential change in BrdU-positive hK nuclei, and b is the y-intercept that represents the initial number of BrdU-positive hK nuclei. This equation was derived from regression performed using the observation period to predict the natural log-transformed, BrdU-positive nuclei. From this equation, the half-life of the BrdU-positive basal hK was calculated as t1/2 = ln2/m, and expressed for serial chase data as the label-retention 50 (LR50) which is the reciprocal of the doubling time. For serial assessments of immediate labeling, the rate is defined as the label-uptake 50 (LU50) to characterize any change in the rate of uptake as a function of time after grafting. Coefficients of determination (R2) were calculated by simple linear regression.

RESULTS

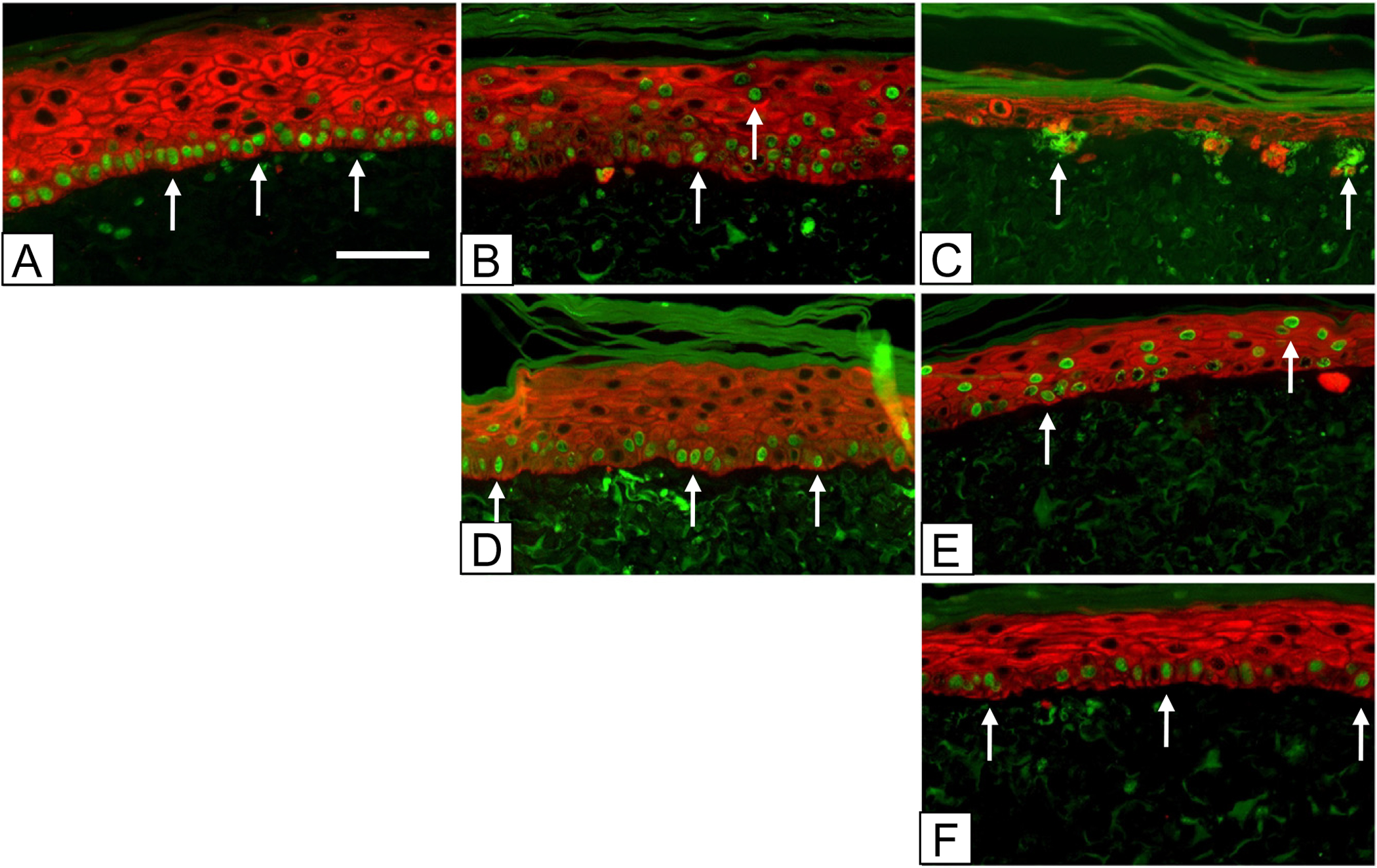

In vitro assessment of keratinocyte labeling is shown qualitatively in Figure 1, and quantitatively in Figure 2. BrdU labeling of hK in ESS at incubation days 5–7 with chase on day 8 (Figure 1A) was uniform and limited almost completely to the basal layer (arrows). Chase on incubation days 15 or 22 showed a progressive loss of labeled cells with translocation through the epidermis to be shed from the surface (Figure 1B). By incubation day 22 (Figure 1C), small clusters of label-retaining hK were found in the basal epidermis (arrows). Pulse at incubation days 12–14, with chase on day 15, showed similar labeling of mostly basal keratinocytes as on day 8 (Figure 1D), and progressive loss of labeled nuclei by day 22 (Figure 1E). Pulse at incubation days 19–21 with chase at day 22 showed labeling predominantly in the basal layer of keratinocytes with some thinning of the epidermal component (Figure 1F).

Figure 1.

Immediate and serial chases over 3 weeks in vitro. Nuclei in ESS were stained green with anti-BrdU-FITC at incubation days: (A–C) 5–7 (top row); (D, E) 12–14 (center row); and (F) 19–21 (bottom row). Keratinocytes were stained red with Alexafluor 594 as described in the Methods. Samples were prepared for fluorescence immunohistochemistry at incubation days: (A) 8 (left column); (B, D) 15 (center column); and (C, E, F) 22 (right column). The time course shows a progressive decrease in numbers of labeled nuclei and reorganization of label-retaining keratinocytes into clusters at the basement membrane (arrows). Scale bar = 0.1 mm.

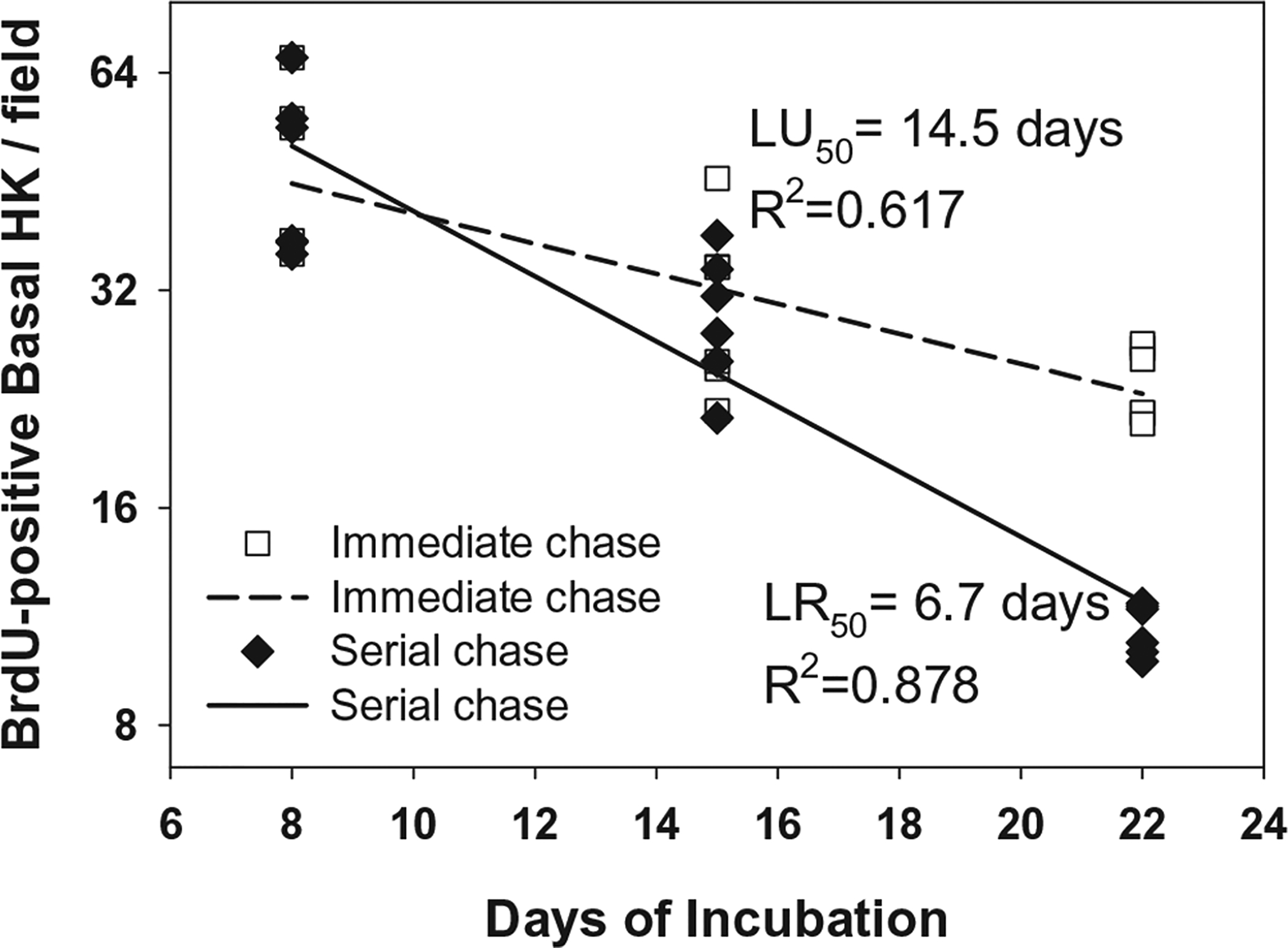

Figure 2.

Plot of immediate and serial chase over 3 weeks in vitro. BrdU-positive keratinocytes per field in vitro. Counts of BrdU-positive keratinocytes showed progressive loss of label, whether pulsed at incubation days 5–7, and chased serially at days 8, 15, and 22, or whether pulsed serially at incubation days 5–7, 12–14, and 19–21, and chased the day following completion of the pulse. Regression analysis of decline in BrdU labeling of single pulse and serial chase generated a proliferative rate (LR50) of 6.7 days, and a coefficient of determination (R2) of 0.878. Weekly pulse with immediate chase generated a LU50 of 14.5 days, R2 value of 0.617.

Quantification of labeling of basal hK is shown in Figure 2. Whether a single pulse of BrdU was administered and chased for 2 weeks (closed diamonds; “serial chase”), or BrdU was pulsed weekly and chased immediately (open squares; “immediate chase”), a progressive decline of labeled hK was found in the basal layer of the epidermal substitute of ESS. The LR50 value for the serial chase was 6.7 days, and the LU50 value for the immediate chase was 14.5 days. Regression analysis correlated well in both the single pulse (R2 = 0.878) and weekly pulse (R2 = 0.617) conditions. The rates of uptake and loss from the basal layer were significantly different statistically.

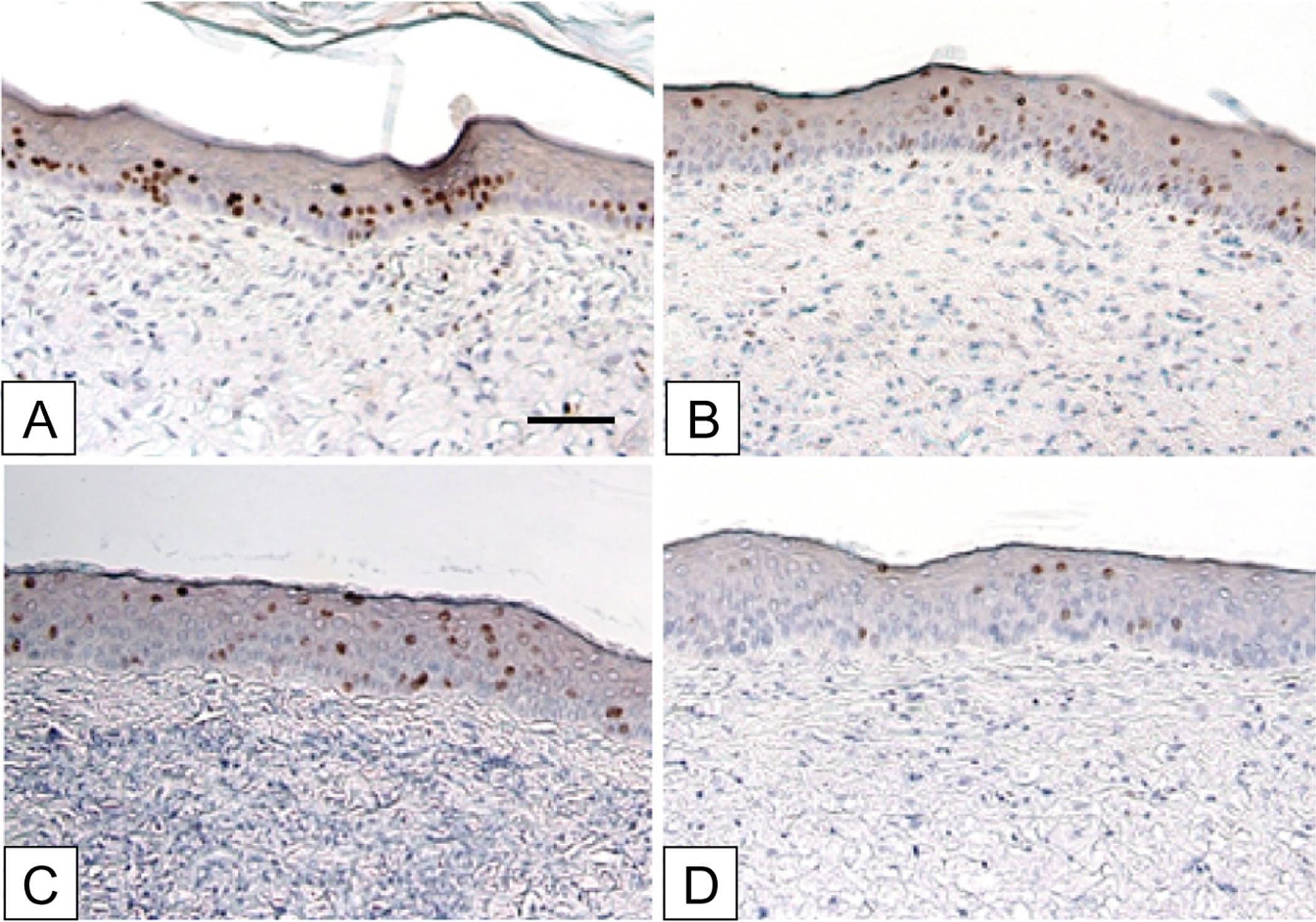

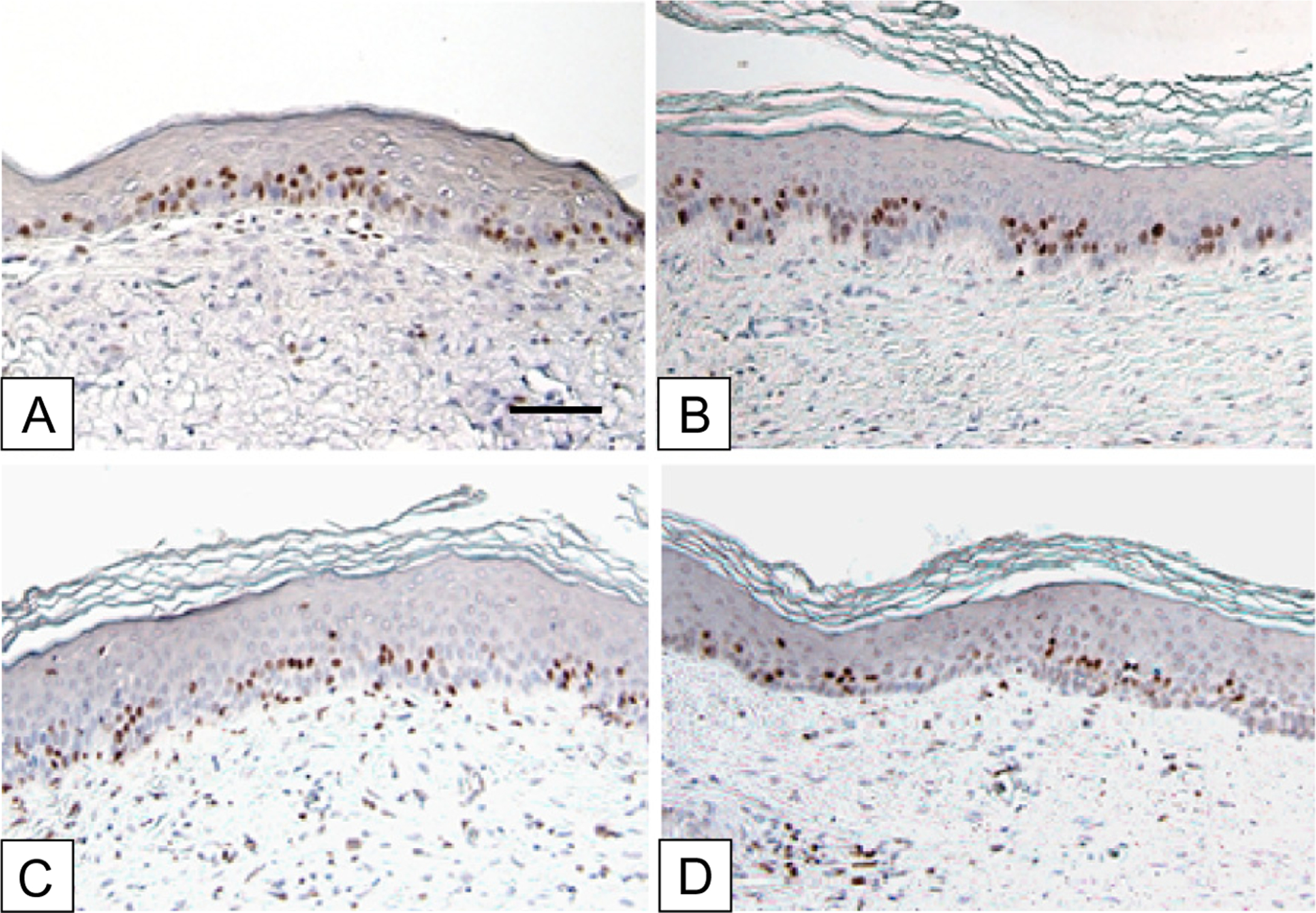

Labeling of healed ESS after grafting to athymic mice and pulsing at POD 17–19 is shown in Figure 3. Immediate chase on POD 20 showed strong labeling in both the basal and suprabasal epidermis (Figure 3A). After a chase of 1 week (Figure 3B), 2 weeks (Figure 3C), or 4 weeks (Figure 3D), a progressive loss of labeled nuclei was observed, with only a very low frequency of labeled nuclei in the basal layer of the epidermis at the 4-week time point. As expected, most of the loss of labeled nuclei occurred by migration through the differentiating epidermis.

Figure 3.

Immunohistochemistry of serial chase of BrdU-positive cells in ESS grafted to athymic mice. BrdU pulses were performed on postoperative days 17–19. Chase days were: (A) 20, (B) 27, (C) 34, (D) 48. The time course shows a progressive decrease of label-retaining cells (brown stain) in the basal epidermis, with migration through the epidermal strata to loss by desquamation. Scale bar = 0.1 mm.

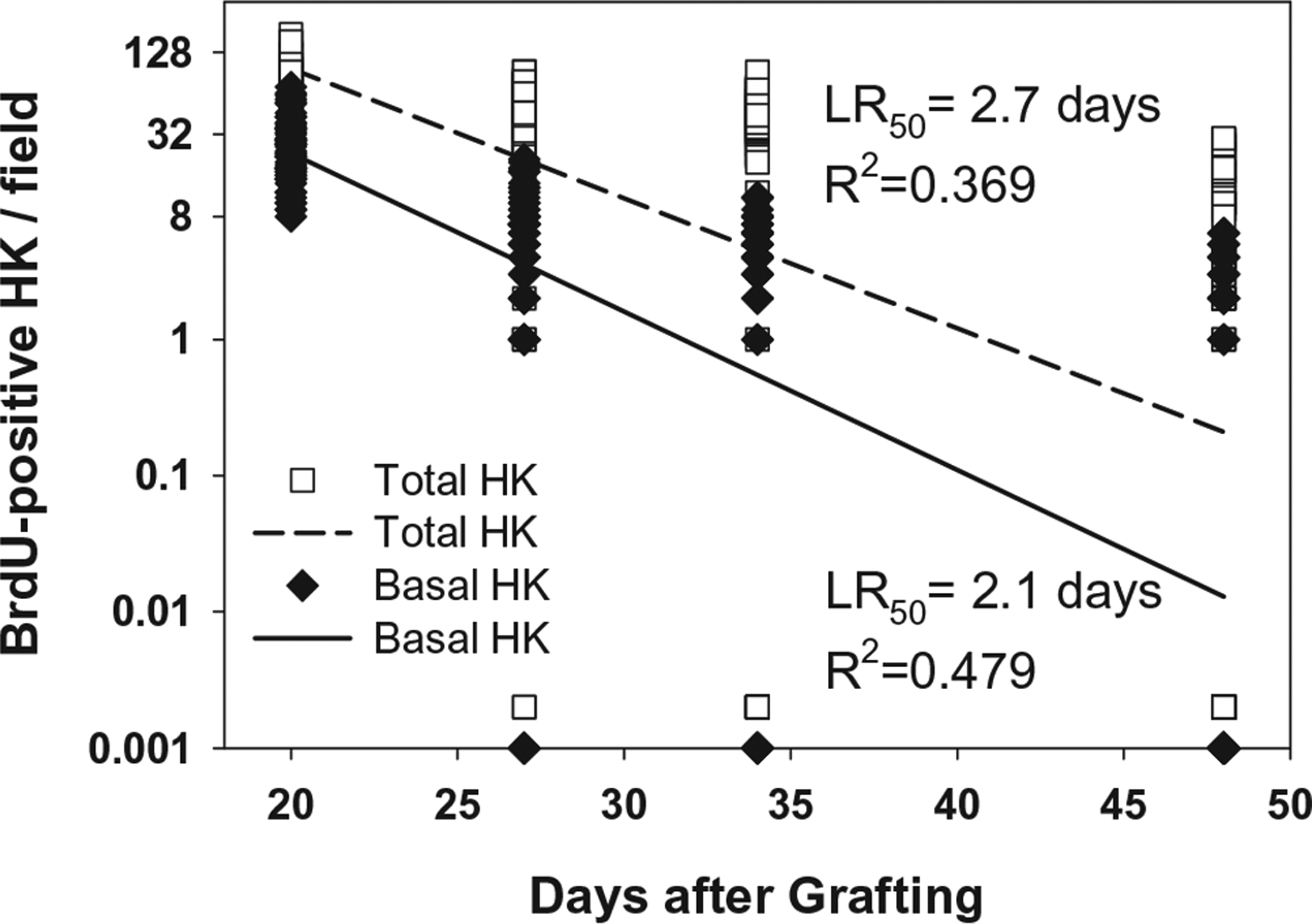

Figure 4 shows quantification of frequencies of total and basal BrdU-positive nuclei in the epidermis at POD 20, 27, 34, and 48. More nuclei labeled in the immediate chase were suprabasal (36.7 ± 2.5) than basal (27.5 ± 2.1). This suggests either some direct uptake of label by transit amplifying keratinocytes or uptake early in the pulse period with loss from the basal layer by the time of the chase which was up to 3 days later. As with samples in vitro, a steady decline in labeled nuclei was observed because most of the labeled cells migrated through the differentiating epidermis and were lost by desquamation. By POD 48, which was 4 weeks after completion of the pulse, only a very low frequency (1.0 ± 0.24) of labeled nuclei could be found in the basal epidermis, and the majority of samples had no detectable BrdU-positive hK in the basal epidermis. Regression analysis showed negative correlation between time and labeled nuclei in the basal (R2 = 0.479), or total (R2 = 0.369) hK populations. According to the slopes of the regression lines, the estimated rates of replication are 2.1 days/cell division for basal hK, and 2.7 days/cell division for total labeled cells. The apparent discrepancy between the regression lines and the plotted data results from increasing numbers of samples over time that had no BrdU-positive hK. Because the regression lines calculate the decreases of BrdU labeling on an exponential scale to determine the inverse of the replication rate, zero values were assigned values three logs below single cells (0.001) for basal hK and 0.002 for total hK. The single symbols near the baseline in the plot represent 5, 10, and 38 of 54 values for basal hK at POD 27, 34, and 48, respectively, and represent 2, 8, and 26 or 54 values for total hK at days 27, 34, and 48.

Figure 4.

Plot of BrdU-positive keratinocytes per field in vivo in serial chase. Counts of BrdU-positive keratinocytes showed progressive loss of label after pulse at POD 17–19, and serial chase at POD 20, 27, 34 and 48. Regression analysis of decline in BrdU labeling of single pulse and serial chase of basal hK generated a LR50 of 2.1 days coefficient of determination (R2) of 0.479. The total labeled hK population showed a LR50 of 2.7 days, and R2 value of 0.369. The apparent discrepancy between the regression lines and the plotted data results from increasing numbers of samples over time that had no detectable BrdU-positive hK. Because the regression lines calculate the decreases of BrdU labeling on an exponential scale to determine the inverse of the replication rate, zero values were assigned values three logs below single cells (0.001) for basal hK, and 0.002 for total hK. Those single symbols in the plot represent 5, 10, and 38 of 54 values for basal hK at postoperative days 27, 34, and 48, respectively, and represent 2, 8, and 26 of 54 values for total hK at days 27, 34, and 48.

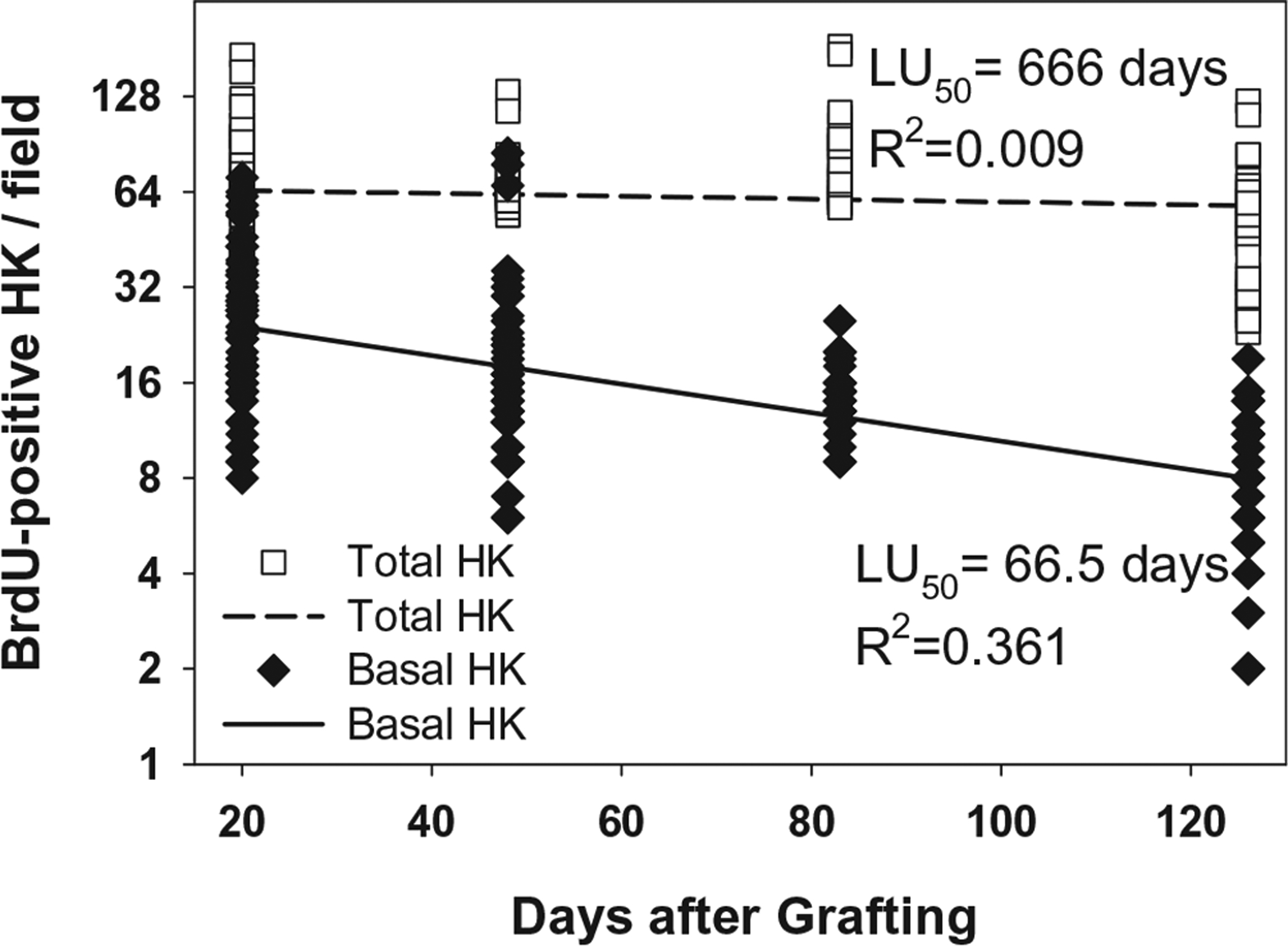

In Figure 5, the immediate chase at POD 20 is compared to immediate chases at POD 48, 83, and 126. Similar patterns of labeled nuclei were observed in both the basal and lower spinous strata. Quantification in Figure 6 shows a negative rate of basal cell labeling as a function of time with a coefficient of determination of 0.361. Quantification of total labeled cells showed no statistical differences among immediate chases at POD 20, 48, 83, and 126.

Figure 5.

Immunohistochemistry of immediate chase of BrdU-positive cells in ESS grafted to athymic mice. BrdU pulse days 17–19, 45–47, 80–82, 123–125. Chase days: (A) 20, (B) 48, (C) 83, (D) 126. The time course shows a progressive decrease of label-uptake in the basal hK, but no significant difference in the total labeling of all hK. This result suggests a shift over time in the proliferative population from the basal compartment to the transit-amplifying cells of the epidermis. Scale bar = 0.1 mm.

Figure 6.

Plot of BrdU-positive keratinocytes per field in vivo in immediate chase. Counts of BrdU-positive keratinocytes showed progressive decrease of label uptake after pulses at POD 17–19, POD 45–47, POD 80–82, and POD 123–125, and chases the following day. Regression analysis of BrdU labeling of basal hK generated a LU50 of 66.5 days coefficient of determination (R2) of 0.361. The total labeled hK population showed a LU50 of 666 days, and R2 value of 0.009, or essentially no change during this observation period.

DISCUSSION

Data from this study show high proportions of BrdU labeling of keratinocytes both in vitro and in vivo, with progressive loss of labeled nuclei over time. Although not surprising, these results confirm a rate of replication in this engineered skin model that is higher than the approximate doubling time of 14 days in uninjured human skin.5 The hyperproliferative phenotype of cells in ESS is demonstrated clearly by the nearly absolute and exclusive labeling in vitro of basal keratinocytes. Prior to grafting, the elevated mitotic rate of hK in ESS may be attributed, in part, to retained EGF from culture medium during the initial 3 days of incubation. However, exogenous EGF would be depleted by the time of grafting at incubation day 15. Another important source of mitogens in ESS are the high-density populations of hK and hF that synthesize and release multiple growth factors including transforming growth factor-α, amphiregulin, epiregulin, and keratinocyte growth factor that act by autocrine and paracrine mechanisms through the EGFR.13–16 Because of these endogenous ligands of EGFR in ESS, exogenous EGF is removed from the medium UCMC161 to slow the mitotic rate in hK, and allow epidermal stratification and differentiation to proceed. The hyperproliferative phenotype has been characterized by microarray analysis and includes up-regulation of multiple genes involved in DNA synthesis and cell division.39,40 The persistence of high rates of label uptake at more than 4 months after grafting of ESS suggests that the hyper-proliferation in the human epidermis may be related to the high rate of systemic metabolism of the murine host. Factors in the murine host that are likely to contribute to an elevated mitotic rate in hK after grafting are the murine metabolic rate, which is approximately seven times that of humans,41 and a low-level inflammatory process despite the absence of T-cell mediated graft rejection. Although each of these factors is recognized to affect the mitotic rate of hK in ESS after grafting, the interpretation of the data remains unchanged. Namely, there is a progressive loss of incorporated label over weeks to months after grafting, and the rate of incorporation of label remains relatively constant for several months after grafting in this model.

The high rate of loss of BrdU-positive hK from basal layer after grafting (Figure 3; LR50 = 2.1 days) indicates an accelerated rate of mitosis in basal keratinocytes which may affect long-term stability of engineered skin grafts. Data in Figure 4 extend to POD 48, or 28 days after the pulse of BrdU, but data from two later time points at POD 83 and 126 were also collected. Those data had so few labeled nuclei that mean values for those time points were well below one cell per field, and introduced significant error into the calculation of the LR50. At POD 48, the majority of fields had no positive basal keratinocytes which contributed to the relatively rapid calculated rate of mitosis. The increasing frequencies of samples with zero labeled nuclei at serial time points also contributed to apparent discrepancy between the positive data values, and the slopes of the regression lines in Figure 4. Therefore, the calculated rate of mitosis depends on samples with no detectable BrdU labeling as much as it does on detection of positive BrdU labeling. The pattern and distribution of BrdU labeling of human ESS in mice is atypical of uninjured skin.42–44 In the absence of hair follicles, all of the labeled cells reside in a location analogous to the interfollicular epidermis. Paracrine, neuroendocrine, or mechanical factors which may down-regulate cell proliferation in the bulge or papillary regions of the hair follicle of uninjured human skin are absent. Therefore, a somewhat elevated proliferative rate may result, in part, from a lack of negative regulation of the cell cycle. If so, and if the lifespan of keratinocyte stem cells is finite, it would be anticipated that engineered skin would “age” prematurely. Determination of keratinocyte life span in humans after grafting of engineered skin would allow comparison to uninjured skin, but that comparison was beyond the scope of this study. Evaluation of epidermal cell kinetics in humans would also need to consider factors such as a donor’s age, vascular supply at the recipient site, solar exposure, or mechanical stimuli from the environment.

Lack of correlation between immediate chase of the hK population and time after grafting (Figure 6) suggests that hypertrophy persists in this murine model for more than 18 weeks. The persistence of hypertrophy for this period of time may be attributed either to hypermetabolism in the healing and remodeling wound, to hypermetabolism of the murine model,41 or both. Protracted hypertrophy may also result, in part, from recognition of the human graft by immune effectors from the host other than T-cells. Clearly, there is an inflammatory infiltrate immediately after grafting that subsides with time, but not completely (data not shown). Furthermore, a progressive normalization of the hypertrophic phenotype in ESS has been characterized in microarray analyses before and after grafting to athymic mice.45 Interestingly, a negative correlation was found between the immediate chase of the basal cell population and time indicating that the rate of proliferation in the basal population decreases slowly with time. In consideration that the labeling of the total population remains relatively constant during this period, the data suggest a simultaneous increase of DNA synthesis in the transit-amplifying keratinocytes of the epidermis.

BrdU incorporated in vitro could not be found after more than 1 week in vivo (data not shown). This suggests that the label is rapidly lost which may result from the surge of cellular proliferation that occurs immediately after grafting. In general, the technical difficulty of performing the in vivo experiments was greater than expected. Multiple pulses of BrdU over multiple days and multiple routes of administration were needed to find labeling in the grafted engineered skin. This may result from less vascular supply as single-day or single routes of pulses were found to label surrounding murine skin, but not engineered human skin.

Data for label uptake (Figures 2 and 6) reflect the biological stability of ESS in vitro and in vivo. Although some models of cultured epithelium have been shown to remain metabolically active for several months in vitro,46,47 all models of engineered skin are inherently unstable and deteriorate in culture. The deterioration is readily attributed to deficiencies in the culture conditions which fail to provide the physiologic systems required to maintain biological equilibrium. After transplantation and engraftment, the systemic physiology (e.g., nutrient supply, waste elimination, immune protection) of the host stabilizes the implant. Consequently, in vitro (Figure 2), the LU50 of the basal hK population declines relatively rapidly (LU50 = 14.5 days; R2 = 0.617), but the LU50 of the basal hK in vivo (Figure 6) extends much longer (LU50 = 66.5 days; R2 = 0.361) demonstrating greater stability. Importantly, it is plausible that the labeling regimen in this study, twice daily for 3 days, may have failed to label keratinocyte stem cells that did not synthesize DNA during the pulse period. Cell cycle times of human epidermal keratinocytes in situ have been estimated at 10–20 days, and cycle times for stem cells in selected niches may be longer.5 Therefore, the pulse period of 3 days may not have labeled the majority of slow cycling keratinocyte stem cells.

Not included in the experimental design of this study was normal human skin immediately after acquisition as surgical discard or similar samples grafted to athymic mice. Each of these reference conditions would help with interpretation of the degree to which the murine model influences the replication rates of the keratinocytes, and they are planned for future studies. The most valid samples would be skin samples collected from subjects at serial time points after grafting, but, unfortunately, those kinds of studies are not practical. For burns, the small number of patients, and the ethical considerations of repeatedly wounding a grafted burn make such studies difficult to justify. These studies also did not determine the ambient mitotic rate and cell cycle duration which may be determined by labeling for increasing time periods (e.g., 1, 4, 12, 24 hours) to determine the time required for BrdU uptake in all basal cells.5

Maintaining the epidermal stem cell phenotype is critical for current and future models of cell transplantation for therapeutic purposes. Understanding and regulating the proliferative potential of keratinocytes provides the biological basis both for tissue function and long-term stability in wound care, and for the development of epidermal adnexi (hair, glands) in advanced models of engineered skin. Previous studies have shown repeatedly that the epidermis of ESS supports epidermal pigmentation which develops much more slowly than epithelialization. Very recently, this model has also supported organization of putative hair follicles after grafting to athymic mice.48,49 Restoration of epidermal adnexi will require extended periods for induction of signaling pathways that are specific to each structure and its respective physiologic function. Insufficient proliferative potential may limit the possibilities for restoration of complete cutaneous anatomy and physiology. Conversely, regulation of the stem cell phenotype in epidermal keratinoctyes may be expected to promote improved healing and long-term stability of wounds closed with ESS.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Deanna Leslie for histology, Chris Lloyd and John Besse for biopolymer fabrication, Rachel Zimmerman and William Kossenjans for preparation of nutrient media, and Laura James for statistical analyses. These studies were supported entirely by NIH grant GM079542, and Shriners Hospitals for Children grant #84050.

DISCLOSURE OF FINANCIAL INTEREST

Dr. Boyce is the inventor named on patents and patent applications assigned to the University of Cincinnati and Shriners Hospitals for Children according to their intellectual property policies. Patents, patent applications, and other intellectual property pertaining to ESS are licensed to Cutanogen Corporation which was founded by Dr. Boyce, and in which he has past and present financial interests. Dr. Boyce resigned as an officer of Cutanogen in 2006, and he has no authority or responsibility for Cutanogen’s current activities. Dr. Boyce also serves currently as a paid consultant to Aderans Research, Inc.

REFERENCES

- 1.Webb A, Li A, Kaur P. Location and phenotype of human adult keratinocyte stem cells of the skin. Differentiation 2004; 72: 387–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lavker RM, Sun TT, Oshima H, Barrandon Y, Akiyama M, Ferraris C, Chevalier G, Favier B, Jahoda CA, Dhouailly D, Panteleyev AA, Christiano AM. Hair follicle stem cells. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc 2003; 8: 28–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bickenbach JR, Grinnell KL. Epidermal stem cells: interactions in developmental environments. Differentiation 2004; 72: 371–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Claudinot S, Nicolas M, Oshima H, Rochat A, Barrandon Y. Long-term renewal of hair follicles from clonogenic multipotent stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2005; 102: 14677–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dover R, Wright NA. The cell proliferation kinetics of the epidermis. In: Goldsmith LA, editor. Physiology, biochemistry, and molecular biology of the skin. New York: Oxford University Press, 1991: 239–65. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Watt FM, Jensen KB. Epidermal stem cell diversity and quiescence. EMBO Mol Med 2009; 1: 260–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rue LW, Cioffi WG, McManus WF, Pruitt BA. Wound closure and outcome in extensively burned patients treated with cultured autologous keratinocytes. J Trauma 1993; 34: 662–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Falanga V, Sabolinski M. A bilayered living skin construct (APLIGRAF) accelerates complete closure of hard-to-heal venous ulcers. Wound Rep Reg 1999; 7: 201–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heimbach DM, Warden GD, Luterman A, Jordan MH, Ozobia N, Ryan CM, Voigt DW, Hickerson WL, Saffle JR, DeClement FA, Sheridan RL, Dimick AR. Multicenter postapproval clinical trial of Integra dermal regeneration template for burn treatment. J Burn Care Rehabil 2003; 24: 42–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gravante G, Di Fede MC, Araco A, Grimaldi M, De AB, Arpino A, Cervelli V, Montone A. A randomized trial comparing ReCell system of epidermal cells delivery versus classic skin grafts for the treatment of deep partial thickness burns. Burns 2007; 33: 966–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Driskell RR, Clavel C, Rendl M, Watt FM. Hair follicle dermal papilla cells at a glance. J Cell Sci 2011; 124 (Pt 8): 1179–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Proulx S, Fradette J, Gauvin R, Larouche D, Germain L. Stem cells of the skin and cornea: their clinical applications in regenerative medicine. Curr Opin Organ Transplant 2011; 16: 83–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shirakata Y Regulation of epidermal keratinocytes by growth factors. J Dermatol Sci 2010; 59: 73–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cook PW, Pittelkow MR, Shipley GD. Growth factor-independent proliferation of normal human neonatal keratinocytes: production of autocrine- and paracrine-acting mitogenic factors. J Cell Physiol 1991; 146: 277–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cook PW, Mattox PA, Keeble WW, Pittelkow MR, Plowman GD, Shoyab M, Adelman JP, Shipley GD. A heparin sulfate-regulated human keratinocyte autocrine factor is similar or identical to amphiregulin. Mol Cell Biol 1991; 11: 2547–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Root LL, Shipley GD. Human dermal fibroblasts express multiple bFGF and aFGF proteins. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol 1991; 27A: 815–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boyce ST. Epidermis as a secretory tissue. J Invest Dermatol 1994; (editorial)102: 8–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ito M, Cotsarelis G. Is the hair follicle necessary for normal wound healing? J Invest Dermatol 2008; 128: 1059–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang CC, Cotsarelis G. Review of hair follicle dermal cells. J Dermatol Sci 2010; 57: 2–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chuong CM, Cotsarelis G, Stenn K. Defining hair follicles in the age of stem cell bioengineering. J Invest Dermatol 2007; 127: 2098–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boyce ST, Supp AP, Swope VB, Warden GD. Vitamin C regulates keratinocyte viability, epidermal barrier, and basement membrane in vitro, and reduces wound contraction after grafting of cultured skin substitutes. J Invest Dermatol 2002; 118: 565–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boyce ST, Kagan RJ, Greenhalgh DG, Warner P, Yakuboff KP, Palmieri T, Warden GD. Cultured skin substitutes reduce requirements for harvesting of skin autograft for closure of excised, full-thickness burns. J Trauma 2006; 60: 821–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Swope VB, Supp AP, Boyce ST. Regulation of cutaneous pigmentation by titration of human melanocytes in cultured skin substitutes grafted to athymic mice. Wound Rep Reg 2002; 10: 378–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barai ND, Supp AP, Kasting GB, Visscher MO, Boyce ST. Improvement of epidermal barrier properties in cultured skin substitutes after grafting onto athymic mice. Skin Pharmacol Physiol 2006; 20: 21–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Supp DM, Supp AP, Bell SM, Boyce ST. Enhanced vascularization of cultured skin substitutes genetically modified to over-express vascular endothelial growth factor. J Invest Dermatol 2000; 114: 5–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.LePoole IC, Boyce ST. Keratinocytes suppress transforming growth factor beta-1 expression by fibroblasts in cultured skin substitutes. Br J Dermatol 1999; 140: 409–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goretsky MJ, Harriger MD, Supp AP, Greenhalgh DG, Boyce ST. Expression of interleukin 1a, interleukin 6, and basic fibroblast growth factor by cultured skin substitutes before and after grafting to full-thickness wounds in athymic mice. J Trauma 1996; 40: 894–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boyce ST, James JH, Williams ML. Nutritional regulation of cultured analogues of human skin. J Toxicol Cutaneous Ocul Toxicol 1993; 12: 161–71. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boyce ST, Kagan RJ, Meyer NA, Yakuboff KP, Warden GD. The 1999 Clinical Research Award. Cultured skin substitutes combined with Integra to replace native skin autograft and allograft for closure of full-thickness burns. J Burn Care Rehabil 1999; 20: 453–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boyce ST. Methods for the serum-free culture of keratinocytes and transplantation of collagen-GAG-based skin substitutes. In: Morgan JR, Yarmush ML, editors. Methods in molecular medicine, vol. 18: tissue engineering methods and protocols. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press Inc., 1999: 365–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boyce ST, Ham RG. Calcium-regulated differentiation of normal human epidermal keratinocytes in chemically defined clonal culture and serum-free serial culture. J Invest Dermatol 1983; 81 (Suppl. 1): 33s–40s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boyce ST, Christianson DJ, Hansbrough JF. Structure of a collagen-GAG dermal skin substitute optimized for cultured human epidermal keratinocytes. J Biomed Mater Res 1988; 22: 939–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Powell HM, Boyce ST. EDC cross-linking improves skin substitute strength and stability. Biomaterials 2006; 27: 5821–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Swope VB, Supp AP, Schwemberger S, Babcock GF, Boyce ST. Increased expression of integrins and decreased apoptosis correlate with increased melanocyte retention in cultured skin substitutes. Pigment Cell Res 2006; 19: 424–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kalyanaraman B, Boyce S. Assessment of an automated bioreactor to propagate and harvest keratinocytes for fabrication of engineered skin substitutes. Tissue Eng 2007; 13: 983–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Supp DM, Wilson-Landy K, Boyce ST. Human dermal microvascular endothelial cells form vascular analogs in cultured skin substitutes after grafting to athymic mice. FASEB J 2002; 16: 797–804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Swope VB, Farooqui JZ, Can G, Boyce ST. Expression of insulin-like growth factor-1 by cultured skin substitutes. Wound Rep Reg 1997; 5: A125. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Swope VB, Supp AP, Greenhalgh DG, Warden GD, Boyce ST. Expression of insulin-like growth factor-I by cultured skin substitutes does not replace the physiologic requirement for insulin in vitro. J Invest Dermatol 2001; 116: 650–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smiley AK, Klingenberg JM, Aronow BJ, Boyce ST, Kitzmiller WJ, Supp DM. Microarray analysis of gene expression in cultured skin substitutes compared with native human skin. J Invest Dermatol 2005; 125: 1286–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Klingenberg JM, McFarland KL, Friedman AJ, Boyce ST, Aronow BJ, Supp DM. Engineered human skin substitutes undergo large-scale genomic reprogramming and normal skin-like maturation after transplantation to athymic mice. J Invest Dermatol 2010; 130: 587–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Terpstra AH. Differences between humans and mice in efficacy of the body fat lowering effect of conjugated linoleic acid: role of metabolic rate. J Nutr 2001; 131: 2067–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hsu YC, Pasolli HA, Fuchs E. Dynamics between stem cells, niche, and progeny in the hair follicle. Cell 2011; 144: 92–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nowak JA, Polak L, Pasolli HA, Fuchs E. Hair follicle stem cells are specified and function in early skin morphogenesis. Cell Stem Cell 2008; 3: 33–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Poojan S, Kumar S. Flow cytometry-based characterization of label-retaining stem cells following transplacental BrdU labelling. Cell Biol Int 2010; 35: 147–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smiley AK, Klingenberg JM, Boyce ST, Supp DM. Keratin expression in cultured skin substitutes suggests that the hyperproliferative phenotype observed in vitro is normalized after grafting. Burns 2006; 32: 135–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gazel A, Ramphal P, Rosdy M, De WB, Tornier C, Hosein N, Lee B, Tomic-Canic M, Blumenberg M. Transcriptional profiling of epidermal keratinocytes: comparison of genes expressed in skin, cultured keratinocytes, and reconstituted epidermis, using large DNA microarrays. J Invest Dermatol 2003; 121: 1459–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Parenteau NL, Bilbo P, Nolte CJ, Mason VS, Rosenberg M. The organotypic culture of human skin keratinocytes and fibroblasts to achieve form and function. Cytotechnology 1992; 9: 163–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sriwiriyanont P, Hachiya A, Pickens WL, Moriwaki S, Kitahara T, Visscher MO, Kitzmiller WJ, Bello A, Takema Y, Kobinger GP. Effects of IGF-binding protein 5 in dysregulating the shape of human hair. J Invest Dermatol 2011; 131: 320–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sriwiriyanont P, Maier EA, Lynch KA, Supp DM, Boyce ST. Dermal papilla cells promote trichogenesis in engineered skin substitutes. J Invest Dermatol 2011; 131 (S1): S79. [Google Scholar]