Abstract

Aims and objectives:

The role of professional doctorates is receiving increased attention internationally. As part of building the rigour and scholarship of these programmes, we assessed projects undertaken as part of a doctor of nursing practice (DNP) programme at Johns Hopkins University. Recommendations for programme development in professional doctorates are provided.

Background:

Past research has described the methodologic limitations and dissemination of DNP projects. However, few studies have provided recommendations for strengthening these projects and alternative strategies for achieving scale in larger student cohorts.

Design:

A descriptive study reported in accordance with STROBE guidelines.

Methods:

From 2009–2018, 191 final DNP project reports were obtained from the DNP programme administrator. Essential project characteristics from the papers were extracted, including use of theoretical framework, design, setting, sample and dissemination through publication. To determine whether the results of the projects had been published, the title and student’s name were searched in Google Scholar and Google.

Results:

Of the 191 projects, 83% focused on adults and 61% were conducted in the hospital setting. Sample sizes ranged from 7 to 24,702. Eighty per cent of the projects employed a pretest/post-test design, including both single and independent groups. The projects spanned six overarching themes, including process improvement, clinician development, patient safety, patient outcome improvement, access to care and workplace environment. Twenty-one per cent of the project findings were published in scholarly journals.

Conclusions:

Conducting a critical review of DNP projects has been useful in refining a strategy shifting from incremental to transformative changes in advanced practice.

Keywords: doctoral nursing education, information dissemination, programme sustainability, study design

1 |. INTRODUCTION

As nursing is a practice discipline, there is a strong movement to recognise this significance at the level of the terminal degree (Fulton, Kuit, Sanders, & Smith, 2012). As long ago as the late 1970s, there have been widespread calls worldwide to bring doctoral education closer to practice (Yam, 2005). The professional doctorate has emerged internationally to satisfy university requirements for a doctoral degree and meet the needs of various professional groups by preparing students to work within a professional context (Yam, 2005). The professional doctorate is widespread and increasingly adopted by varied professions, often making it challenging to clearly delineate this credential between disciplines. However, the 2005 task force by the Council for Higher Education Accreditation and Council of Graduate Schools identified a number of core characteristics, recommending that the professional doctorate should (a) address an area of professional practice where other degrees are not currently meeting employer needs, (b) emphasise applied or clinical research or advanced practice and (c) include leaders of the profession who will drive the creative and knowledge-based development of its practices and the development of standards for others (CGS in the USA, 2007; DEST, 1997). Professional doctorates have also grown more prevalent internationally (CGS, 2006; CGS in the USA, 2007; DEST, 1997; Mellors-Bourne, Robinson, & Metcalfe, 2016) with the doctor of nursing practice (DNP) being one such professional doctorate that has been developed in recent years (CGS in the USA, 2007).

The professional doctorate typically requires students to complete a dissertation or project to fulfil the requirements of a doctoral degree (CGS in the USA, 2007). In 2015, the American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN) issued a report from the Task Force on the implementation of the DNP with a section addressing DNP projects. This document explained that DNP programmes prepare nurses in advanced nursing practice to influence health care outcomes at the individual or population level. It also provided six key elements that should be present in all DNP projects: (a) focus on a change impacting healthcare outcomes, (b) systems or population approach, (c) demonstration of implementation in the appropriate arena of practice, (d) plan for sustainability, (e) evaluation of a process and/or outcomes and (f) provide for future practice scholarship (AACN, 2015). In 2018, a report from AACN provided more information on the scholarship of practice and gave several examples of projects in this category. While the report mentions the translation of research, quality improvement initiatives and the use of big data and system-wide data in the scholarship of practice, it avoids being overly prescriptive about methods to use in the scholarship of practice (AACN, 2018). There have been several papers in the literature describing limitations in the design and reporting of DNP projects both within and across DNP programmes. The Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing is in its 130th year as a school and 10th year as a DNP programme. The authors take this occasion to describe and critique the DNP projects conducted by students in our DNP programme since its outset and provide recommendations to strengthen our programme that we hope may be useful to faculty in other schools with DNP programmes.

2 |. BACKGROUND

There have been several papers in the nursing literature between 2013–2019 that have described curricular and educational approaches to guiding students in the development of DNP projects (Brown & Crabtree, 2013; Kirkpatrick & Weaver, 2013; Waldrop, Caruso, Fuchs, & Hypes, 2014), DNP project topics (Howard & Williams, 2017; Minnick, Kleinpell, & Allison, 2019) and the quality of measurement and analyses used in DNP project reports across schools in the USA (Dols, Hernandez, & Miles, 2017; Roush & Tesoro, 2018). Roush and Tesoro (2018) examined 65 DNP project reports stored in the electronic dissertation and thesis database, ProQuest®. The authors reported substantial methodological limitations in the project reports including inadequate description of the methods used for sample selection, intervention implementation and data analyses. The authors had several recommendations including greater attention to teaching these methods and publication of the DNP projects to allow for ongoing evaluation across schools.

Earlier reports of DNP projects at Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing included a report by Terhaar and Sylvia in 2015 examining 80 DNP project reports from the first five years of the DNP programme. The most common method of analysis of project findings was descriptive–comparative and more than half of the students used a pretest/post-test design. The authors noted that the scope and complexity of the projects increased from the first cohort to the fifth cohort and that students in the earlier cohorts were more likely to examine changes in knowledge than students in the later cohorts. In another paper describing publication outcomes of DNP students at Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing, Becker, Johnson, Rucker, and Finnell (2018) described the 156 students enrolled in between 2009–2016 and any publications that they had during their studies and after graduation. Fifty-eight (37%) students published their DNP Project papers and 20 (13%) published integrative reviews of the literature.

2.1 |. Description of the Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing DNP Executive Program

Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing launched a Post-Master’s DNP Executive Program in 2008 that was accredited by the Maryland Higher Education Commission and the Commission on Collegiate Nursing Education. The six-semester programme includes coursework in quality improvement for evidence-based practice, graduate-level biostatistics, finance, informatics, health policy and leadership. At least one full-time faculty member and an organisational mentor guide the student in completing a DNP Project that is relevant to the student’s practice. DNP project proposals are reviewed by the Johns Hopkins University Medicine Institutional Review Board (IRB). Most have been classified as performance improvement projects. A few have undergone an IRB review for human subjects research. Due to the large increases in number of students and subsequently DNP projects, the Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing has established its own internal IRB, in collaboration with the Johns Hopkins University Medicine IRB, to review future DNP projects starting in 2020. The School of Nursing internal IRB will decide whether projects are performance improvement, if projects are thought to be human subjects research, they will still be submitted to the Medicine IRB for review.

Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing saw its first DNP cohort graduate in 2009. The authors take this occasion on the 10th year of the DNP programme and the 130th year of Johns Hopkins University Nursing to describe the DNP projects completed by students in this programme up to 2018. In this descriptive study, we follow 10 cohorts of students and aim to (a) evaluate the publication of project outcomes over time; (b) describe the components of the DNP projects, including the topics addressed in the projects, theoretical underpinnings, designs, samples and methods of analysis; and (c) recommendations for the future direction of DNP projects and education. We offer recommendations for strengthening the DNP projects at our own school including a template to guide construction and reporting of the projects and a summary of common methods of analysis employed in these projects that may be useful to faculty and students in other schools with DNP programmes.

3 |. METHODS

Using the method of a descriptive study design, assessment of 191 projects submitted from cohorts graduating between 2009–2018, as part of course work requirements were assessed. Final versions of the DNP project reports were submitted to the DNP programme administrator to be retained on file as part of the collection of scholarly products of the DNP programme. The authors extracted essential project characteristics from the papers including use of theoretical framework, design, setting, sample and dissemination through publication. Three of the authors performed the initial extraction to an Excel spreadsheet. One co-author extracted information from all 191 projects on the DNP project theme, theoretical framework, sample and setting. The projects were then split evenly between the two co-first authors for verifying the previously extracted information and to extract additional information on project design, analysis and publication. All authors discussed any discrepancies and reached consensus to validate the project characteristics and outcomes. To determine whether the results of the projects had been published at any point since the student graduated from the programme, the two co-first authors searched the title and student’s name, from the list of programme graduates obtained from the DNP programme administrator, in Google Scholar and Google. In some cases when no publications were discovered in Google Scholar and Google, the authors also searched PubMed and CINAHL. The study was carried out according to the STROBE guidelines (see Appendix S1). This study was deemed exempt research by the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Institutional Review Board (IRB00248926).

4 |. RESULTS

The authors analysed all 191 DNP Executive project reports and Table 1 provides a summary of the key elements of the DNP projects. Eighty per cent of the projects employed a pretest/post-test design which included both single and independent groups. Sample sizes ranged from 7 to 24,702. Eighty-three per cent of the projects focused on adults and 61% were conducted in the hospital setting. Sixty-seven per cent of the projects did not specify a conceptual framework used.

TABLE 1.

DNP project characteristics

| N = 191 | |

|---|---|

| Design | |

| Pretest/post-testa | 153 (80%) |

| Post-test only | 17 (9%) |

| Randomised controlled trial | 5 (3%) |

| Otherb | 16 (8%) |

| Sample | |

| Patients/family/community members | 79 (41%) |

| Clinicians/Healthcare students and support staff | 55 (29%) |

| Both | 51 (27%) |

| Otherc | 6 (3%) |

| Age | |

| Adults | 159 (83%) |

| Paediatric | 10 (5%) |

| Both | 19 (10%) |

| NAd | 2 (1%) |

| Unknownd | 1 (1%) |

| Setting | |

| Inpatient/ED/OR | 117 (61%) |

| Outpatient/Community/Schools | 60 (31%) |

| Both | 5 (3%) |

| Othere | 9 (5%) |

| Framework | |

| Yes | 63 (33%) |

| No | 128 (67%) |

| Published | |

| Yes | 41 (21%) |

| Nof | 150 (79%) |

Includes: pre- and post-test within a single group, pre- and post-test with independent groups (pre- and postintervention, e.g. historical comparison group) and time-series designs. Three were also mixed-methods studies, with the quantitative arm being pretest–post-test.

Includes: programme development/evaluation, three systematic reviews, proposal of strategies, etc.

Other samples include: laboratory results, articles for reviews, Frederick County Head Start programme, alarms, PICC lines.

NA age for Frederick County Head Start programme, laboratory results; unknown age for not stated.

Includes: not stated, none (as in the case of systematic reviews), solely online education, proposal of strategies, Office of Force Readiness and Deployment.

19 of the 149 that have not been published are from 2018 and may be in the process of being submitted/published.

4.1 |. Project themes

The main themes that were the focus of the DNP projects and one or two examples by theme are included in Table 2. Six overarching themes were identified, including process improvement, clinician development, patient safety, patient outcome improvement, access to care and workplace environment. Many of the projects spanned multiple of the identified themes.

TABLE 2.

DNP project themes

| DNP project themes | Examples of DNP projects |

|---|---|

| 1. Process improvement | |

| a. Screening/early detection | Facilitate the recognition of juvenile fibromyalgia syndrome (JFS) by primary care providers in paediatric clinical setting through the development of a JFS recognition tool, education to providers and implementation of the tool |

| b. Documentation | Create, implement and evaluate a nursing care flow sheet and documentation guideline to improve quality of documentation |

| c. Adherence to guidelines | Development and use of an algorithm and nurse education to improve ED nurses' assessments, documentation and referrals provided to patients regarding intimate partner violence |

| d. Time to health care delivery | Examine the effect of a multidisciplinary system of communication on achieving 90-min first medical contact to open artery goals |

| e. Time to discharge | A care delivery model to facilitate the flow of level-3 patients through the ED to reduce ED crowding |

| f. Reducing readmission rates | Test the feasibility of an advanced practice nurse-led transitional care programme to reduce preventable readmissions |

| 2. Clinician development | |

| a. Leadership development | Development of leadership skills among bedside nurses: succession planning |

| b. Mentorship programmes | Evaluate the effectiveness of a peer-coach model to increase nurse competence in use of electronic health records |

| c. Continuing education to promote quality care | Development of leadership-training curriculum to reduce the prevalence rate of facility-acquired pressure ulcers |

| d. Training/education | Evaluating effectiveness of an educational training intervention to improve provider compliance with ACOG guidelines for HPV/Pap testing for primary screening in low-risk women aged 30+ years |

| e. Provider knowledge | Educational intervention to increase the knowledge of obstetrical providers on the guidelines for foetal echocardiography |

| f. Collaboration/communication | Use real-time data display of patient-specific information to improve communication and teamwork within the operating room suite |

| 3. Patient safety | |

| a. Medical errors | Evaluate a comprehensive laboratory tracking system with a multidisciplinary approach on tracking, follow-up, and reporting of laboratory test results to prevent medical errors |

| b. Medication administration | Increase knowledge among critical care nurses about identifying and reporting medication errors and near miss events, identify barriers in recognising and reporting such events, and pilot test a voluntary electronic reporting system from the Maryland Patient Safety |

| c. Infection control | Use of multidisciplinary strategies, including staff education, catheter care and best maintenance practices to reduce the number of positive urine cultures in critically ill children |

| d. Informed consent | Enhancement of consent process so that patient safety is a priority, and obtaining informed consent is a consistent process |

| 4. Patient outcome improvement | |

| a. Patient health outcomes | Development of checklist to decrease incidence of extubation failure in adult trauma patients |

| b. Patient lifestyle change | Evaluate the relationship between intrinsic and extrinsic motivators and exercise beliefs and attrition and completion rates of senior fit programme participants |

| c. Patient self-care | Test nurse practitioner use of 5A's intervention to improve adult type 2 diabetes self-management |

| d. Patient symptom management | Implement and examine impact of community health educator education intervention on using low-osmolarity oral rehydration solution and zinc supplements to improve home management of diarrhoeal disease in children in rural Nicaragua |

| e. Patient knowledge | The use of a multicomponent intervention to improve knowledge and minimise lymphedema risk among newly diagnosed breast cancer patients |

| f. Patient satisfaction | Develop and explore feasibility and acceptability of a web-based family resource for paediatric obesity prevention in a university health maintenance organisation patient population |

| 5. Access to care | |

| a. Follow-up appointment | To implement and evaluate site-specific appointment keeping processes to increase attendance rates among adult type II diabetics with follow-up appointments |

| b. Transitional care | Accomplish a smooth transition for high-risk neonates from the acute care setting into primary care setting |

| 6. Workplace environment | |

| a. Satisfaction | Number of patient-initiated calls, patients' satisfaction of nursing staffs' response to their calls via semistructured interviews, subset of Press Ganey Satisfaction survey to assess patients' satisfaction of promptness in response to calls and teamwork scores as assessed by the Nursing Teamwork Survey (NTS) |

| b. Retention | Implementation of National Database of Nursing Quality Indicators (NDNQI) Practice Environment survey to provide nurses with data to develop improvement projects that improve taking shift breaks and nurse retention |

| c. Burnout | Examine the effects of compassion fatigue resiliency training on compassion satisfaction, burnout, secondary traumatic stress and resiliency in emergency nurses |

| d.Safety | Impact changes to the work environment have on nurses' perceived and directly observed distractions and interruptions during medication administration |

4.1.1 |. Process improvement

Process improvement projects sought to increase efficiency of health care delivery related to human factors and systems integration. The processes examined included screening for disease conditions and health risks, documentation of care processes, adherence to guidelines, time to healthcare delivery, time to discharge and reduction of readmission rates. One project involved establishing a command centre for a nearly 1,000 bed hospital and examined admissions and interhospital transfers resulting in increased efficiency in these processes throughout the hospital (Newton & Fralic, 2015).

4.1.2 |. Clinician development

Clinician development refers to improving clinician skills, knowledge and abilities. Projects focused on leadership, mentorship, educational approaches and interprofessional training. Multiple dimensions of communication were examined including the content and timing of communication and the confidence of the clinician communicating. Many of these projects measured knowledge before and after an educational intervention. One of these projects involved examining the effectiveness of short, frequent training sessions on nurses’ retention of initial cardiopulmonary resuscitation priorities and the most efficient training interval (Sullivan et al., 2015).

4.1.3 |. Patient safety

Patient safety included patient protection from medical errors and other harms, including projects associated with reducing medical errors and improving medication administration, infection control, and the informed consent process. One of these projects involved examining the effectiveness of a mandatory computerised ordering tool that allowed for early interdisciplinary communication and evaluation by a Peripherally Inserted Central Catheter (PICC) team for suspected PICC infections and thromboses, on decreasing premature PICC removal rates and associated complications (Kim-Saechao, Almario, & Rubin, 2016).

4.1.4 |. Patient outcome improvement

Projects focused on patient outcome improvement in the healthcare setting assessed various aspects of health, lifestyle behaviour, self-care, symptom management, knowledge and satisfaction. One of these projects involved examining the effectiveness of an education programme and increased patient support options, as well as increased provider education on continuous positive airway pressure adherence (Dinapoli, 2015).

4.1.5 |. Access to care

Access to care refers to connections to care, such as improving patient attendance at follow-up appointments, and transitions of care, such as from the acute to the primary care and the paediatric to adult setting. One of these projects involved examining the effectiveness of a telemental health programme, in a rural setting, in improving time to consult as compared to face-to-face groups (Southard, Neufeld, & Laws, 2014).

4.1.6 |. Workplace environment

Workplace environment included patient factors such satisfaction but also improvement of the work environment for nurses and other health professionals. One of these projects involved determining whether the implementation of a standardised handoff tool, reorganising interrupting processes and training on effective handoff communication could reduce the number of interruptions per intershift report (Younan & Fralic, 2013).

4.2 |. Settings

Sixty-one per cent of projects took place in hospital settings including emergency rooms, inpatient medical or surgical units, critical care areas and the operating room. Thirty-one per cent of projects took place in schools, outpatient and community settings. An additional 3% of projects bridged both the hospital and outpatient/community settings.

4.3 |. Samples

Samples included patients, family members, community members, clinicians, students and healthcare support staff. Eighty-three per cent of projects included adult samples and 5% of projects included paediatric samples. An additional 10% of projects included both adult and paediatric samples. Some projects examined a single race or ethnic group. The locations for the projects relative to the university were local, national and global representing countries on multiple continents in North and Central America, Africa and the Middle East.

4.4 |. Theoretical framework

Thirty-three per cent of the reports described a theoretical framework that was used to guide the project. The most common were evidence translation models such as The Knowledge to Action Framework (Graham et al., 2006), the Johns Hopkins University Translating Evidence into Practice Model (Dang & Dearholt, 2017) and the Ottawa Model of Research Use Framework (Logan & Graham, 1998). Some were broadly focused such as Rogers’ Diffusion of Innovation (Rogers, 1962) and process improvement theories including The Content and Process Model of Strategic Change (Pettigrew & Whipp, 1992). Others were focused on specific conditions such as chronic illness and addiction disorders. Examples of these included the Chronic Care Model (Kane, 1999) and the National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STDs and TB Prevention Framework (CDC, 2009).

4.5 |. Designs

The various types of designs used for the projects are summarised in Table 1 and represent the breadth of advanced nursing practice. Eighty per cent of the projects used a pretest–post-test design and one of these was a mixed-methods study design. Some used the same sample while others used two different samples before and after the introduction of an intervention. Still others used post-test only with a historical comparison group. The remainder of the projects used a variety of designs including single sample post-test only, randomised controlled trial design, systematic review and proposal of strategies. Five of the DNP projects used a randomised controlled trial design. However, in these designs the control group largely consisted of usual care and blinding was not used. Four of these randomised controlled trials employed the typical two group, intervention and control design and one study employed a multi-group design.

4.6 |. Analyses

The majority of the projects used univariate analysis including independent or paired t test and chi-square. Only a few of the projects used regression analysis. Most students used the statistical package, SPSS to conduct their analyses. Most reports did not include a power analysis.

4.7 |. Sustainability

Eighteen per cent of reports included a plan for sustainability of the project. For example, many projects involved the adoption of the new performance improvement process in the unit practice or a plan was developed to adopt the new practice in the future.

4.8 |. Publications

All projects were presented orally or as posters. Publications were discovered for 21% of the projects reviewed in both nursing and interdisciplinary journals. The impact factor of these journals ranged from 0.1 to 5.9. These included both specialty journals, such as Resuscitation, Progress in Transplantation and Advances in Neonatal Care, and journals focused on performance improvement such as Journal of Nursing Care Quality.

5 |. DISCUSSION

Many of the projects undertaken as part of the DNP degree were designed to describe the implementation of a new evidence-based practice intervention and the patient and provider outcomes that followed within a particular practice setting. The evolution of our DNP programme has occurred in the context of significant development in both implementation science and quality improvement methodology. Implementation science is the study of methods for promoting the adoption and integration of evidence-based practices, interventions and policies into routine practice and has been codified in frameworks such as the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR, 2019). Similarly, the Standards for QUality Improvement Reporting Excellence have increased both the rigour in design and reporting of quality improvement strategies (Ogrinc et al., 2016). A strength of the DNP programme at Johns Hopkins University is the collaboration among faculty with research and advanced practice expertise in teaching and guiding DNP students in their DNP projects. This collaboration results in a range of methodological approaches to these projects. Cygan and Reed (2019) have described an approach to collaborative DNP-PhD scholarship that is consistent with what we have described here.

Within the curriculum, there is an emphasis on dissemination and all students present their work as an oral presentation or poster presentation at a School of Nursing conference to which our practice partner institutions are invited. In addition, 21% of students generated a peer-reviewed publication reporting the DNP project outcomes. As part of knowledge sharing and exchange, we also encourage students to place their project in the Sigma Theta Tau Virginia Henderson Repository (Sigma Theta Tau, n.d.).

5.1 |. Limitations of this review

This review of DNP projects has some limitations. First, we report that 21% of the projects generated publications. But it can take two or more years for students to publish a paper from their projects so this publication rate may be artificially low. Second, the DNP projects included in this review are solely from the Post-Master’s DNP Executive Track of the DNP programme at Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing. Thus, the findings may not be generalisable to the Post-Baccalaureate DNP Advanced Practice Track at Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing. However, we believe that our recommendations to improve our DNP Executive Track and the guidelines we provide will be useful for faculty in both Tracks. Finally, since this paper has looked at 191 DNP projects over the past 10 years, we provided a general overview of the findings. Faculty may wish to examine various subgroups by population, setting or type of intervention/practice guideline, to provide further detail. More importantly, these data reflect the maturation of the DNP programme and the implementation of the DNP essentials (AACN, 2006) focusing on advanced nursing practice that is evidence-based, innovative and applies credible research findings. We have some exciting new programmes, including the dual degree programmes DNP-PhD and DNP-MBA which will extend our domain-specific knowledge to advance patient outcomes. As many programmes strive internationally to increase the focus on practice doctorate, this reflective analysis provides some useful signposts for increasing both the rigour and programme relevance.

5.2 |. Strengths of projects

One strength of the projects that reflects the strength of the Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing was the international diversity of the projects from countries in North and Central America, Africa and the Middle East. The projects reflected the diversity of nursing practice across these countries such as the nurses’ role in patient education and in leading process improvement initiatives in the practice setting.

Another strength was the number of publications that were generated. We found that 21% of the projects resulted in publication. This was lower than the 37% in a previous report that included DNP projects from Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing up to 2016 by Becker et al. (2018). This may be because these authors, in addition to searching the literature using PubMed and Google Scholar also accepted a print version of a publication provided by the graduate. For this paper, we only searched the literature electronically and did not also examine publications that the graduates provided that were not found in the literature search.

The diversity of the settings in which the projects were conducted demonstrated the opportunities for nurses to lead initiatives resulting in improvements in patient outcomes. They also demonstrate the rich learning opportunities for nurses in DNP programmes to learn from colleagues who practise across the spectrum of healthcare delivery.

5.3 |. Opportunities for future development of DNP projects

In this section, we discuss the implications of our findings for future directions and improvement in DNP projects and education.

5.3.1 |. DNP project reports

Most studies were designed to evaluate factors influencing the translation of an evidence-based intervention into practice. However, one limitation identified was that only 33% of the project reports included the translation framework used although translational frameworks are a required part of the development of their project proposal. Moving forward, we have increased our teaching and guidance about how these frameworks guide the development of the project and how to incorporate the framework into the project report. The majority of our students did not report a power analysis when it would have been appropriate given the design. In order to promote accurate interpretation of the findings, this has become a requirement in cases where the significance of differences between pretest and post-test within a single group or between two or more groups is being assessed. Students have the opportunity to learn these methods in the curriculum and also have access to a designated statistician for consultation.

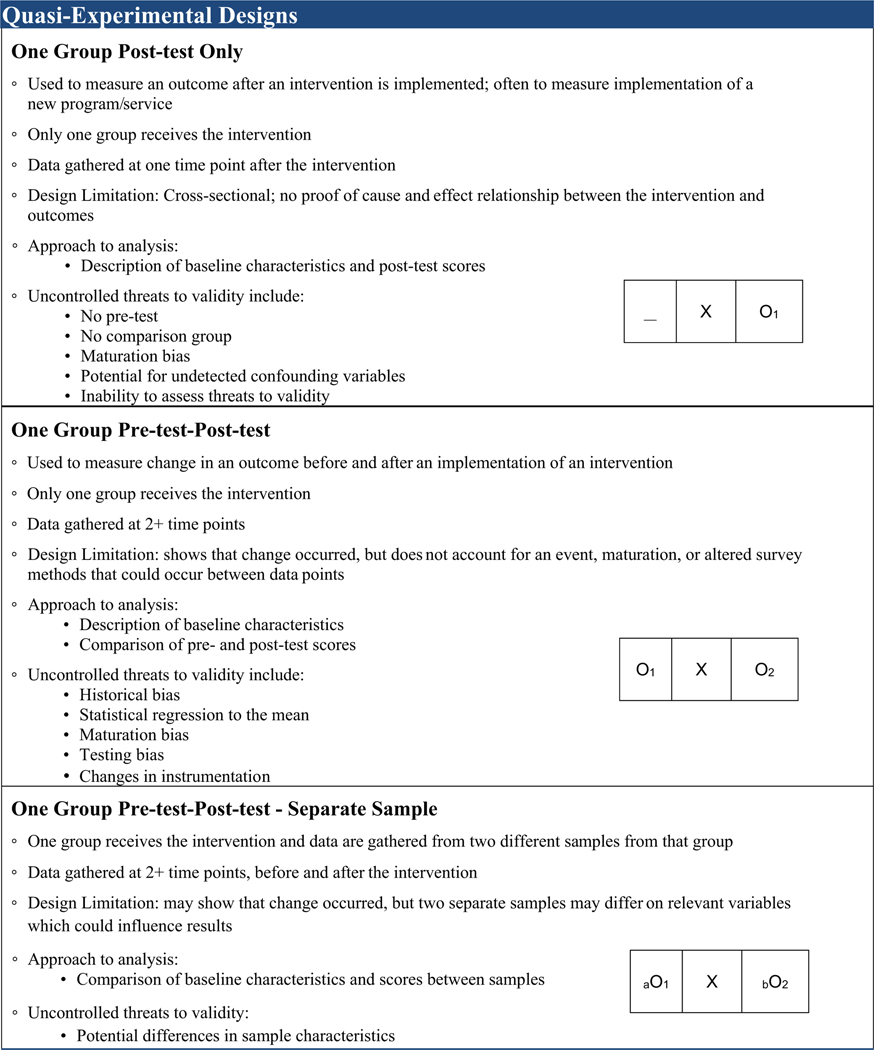

In order to promote coherence between the design used in the project and analysis of findings, we have developed a template to guide faculty and students that may be useful to faculty and students in other DNP programmes (Appendix S2). We have also included a description of common DNP project designs (Figure 1) and analyses (Table 3) to guide faculty and students in project development.

FIGURE 1.

DNP project designs

TABLE 3.

Guidelines for analysis by design

| Ordinal and interval/Ratio dependent variables | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Number of groups in independent variable | Nature of groups in independent variable | Sample size | Distribution of DV | Statistical test | |

| 1 group | N ≥ 30 | Normally distributed | One-sample z test or t test | ||

| N < 30 | Normally distributed | One-sample t test | |||

| Not normal | Sign test | ||||

| 2 groups | Independent | N ≥ 30 | Normally distributed | t test | |

| Not normal | Mann-Whitney U or Wilcoxon rank- sum test | ||||

| N < 30 | Normally distributed | t test | |||

| Not normal | Mann-Whitney U or Wilcoxon rank- sum test | ||||

| Paired | N ≥ 30 | Normally distributed | Paired t test | ||

| Not normal | Wilcoxon signed-rank test | ||||

| N < 30 | Normally distributed | Paired t test | |||

| Not normal | Wilcoxon signed-rank test | ||||

| 3 or more groups | Independent | NA | Normally distributed | 1 factor/IV | One-way ANOVA |

| ≥2 factors/IVs | Two-way or N-way ANOVA | ||||

| Not normal | Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis of variance by ranks | ||||

| Dependent | NA | Normally distributed | Repeated-measures ANOVA | ||

| Not normal | Friedman two-way analysis of variance by ranks | ||||

| Nominal measures | |||||

|

| |||||

| 1 group | np and n(1-p) ≥ 5 | z-approximation | |||

| np or n(1-p) < 5 | Binomial | ||||

| 2 groups | Independent | np < 5 | Fisher exact test | ||

| np ≥ 5 | Chi-squared test | ||||

| Paired/ Case control | McNemar | ||||

| 3 or more groups | Independent | np < 5 | Collapse categories for chi-squared test | ||

| np ≥ 5 | Chi-squared test | ||||

| Dependent | Cochran's Q | ||||

| Regression analysis | |||||

|

| |||||

| Type of data | Distribution of dependent variables | Number of independent variables | Statistical test | ||

| Interval/ratio data | Normally distributed | 1 | Simple linear regression | ||

| >1 | Multiple linear regression | ||||

| Dichotomous data | NA | 1 or more | Binary logistic regression | ||

| Categorical (>2 categories) data | NA | 1 or more IVs | Multinomial regression | ||

5.3.2 |. Scope and depth of DNP projects

Opportunities for advancing the scope and depth of the projects in the future may involve group approaches that would allow two or more students to work on one project. This would allow student groups to focus on several dimensions of the same project. For example, among a student group interested in studying readmission rates among patients with congestive heart failure several dimensions the students could address include the following: lifestyle education, patient and caregiver knowledge, symptom management and follow-up care. This would enable each student to select one dimension and working together, and develop a more comprehensive and effective improvement project. Project design courses would need to incorporate elements on developing cohesive interventions supported by practice guidelines and research findings.

While the AACN supports group projects in which each student is accountable for at least one component of the project and a deliverable (AACN, 2015), we have not yet had a group DNP project at Johns Hopkins University. Moving ahead, we are considering how we might engage students in group projects simultaneously or sequentially at different sites or focusing on different aspects of the same project. We are now finding that when the practice sites offer several potential projects to students and students select from among these, the practice site is more likely to be invested in DNP projects.

5.3.3 |. Sustainability of DNP projects

As noted, only 18% of the project reports included a plan for sustainability. Moving forward, the need for sustainability and ideas on how to achieve sustainability should be included in the curriculum at the beginning of project development. Potential methods for promoting sustainability of DNP projects may be through the pursual of longitudinal DNP projects with more than one DNP student participating. Another aspect in the future that will promote sustainability will be a more formal process for having the practice sites select the projects and having DNP students choose from among projects that are a priority to the clinical partner agency. Some challenges in having partner agencies select the project are that they may want to use a self-designed measure that has not been validated. In the light of this, the programme now seeks to emphasise the need to find validated instruments and guides students to the available resources in order to accomplish this goal.

The process of analysing these projects provided us with insight into some strengths and limitations of our programme and has guided our plans for improving our teaching and learning strategies in this programme. This comprehensive review of DNP projects is a critical process in striving for excellence in academic programming and ensuring fidelity to the DNP essentials in fostering advanced practice. We also consider that the recommendations based on this review have relevance for professional doctorates internationally.

In Table 4, we provide additional recommendations for DNP programmes while conducting programme evaluation.

TABLE 4.

Recommendations for DNP programme evaluation

| Recommendation | Reasoning | Action Steps |

|---|---|---|

| DNP programmes should evaluate their DNP projects over multiple years | • Self-reflection is a critical component of quality improvement methodology to promote rigour (Sun & Cherry, 2019) • Evaluation over multiple years allows perspective on students' understanding of critical curriculum elements • Provides insight into extent faculty are experts in translational frameworks, designs and analyses |

• Conduct programme evaluation as we have done here • Use implementation science (Casey, O' Leary, & Coghlan, 2018; Embree, Meek, & Ebright, 2018) as a framework to promote sustainability and impact of projects • Develop key performance indicators of programme success |

| Determine sustainability and impact of DNP projects | • Maintaining DNP project improvements in the organisational sites is imperative for sustaining impact | • Collaborate with clinical site mentors and graduates to determine if impact described in DNP report has been sustained after graduation • Enhance academic-practice collaboration by identifying DNP projects that are aligned with organisational needs and existing measures. This offers an enhanced and natural opportunity for sustainability and impact evaluation that continues after the studen’s project is completed. This approach supports hospitals pursuing or renewing Magnet designation; repeated measures are critical • Encourage the use of robust theoretical frameworks for practice change and implementation science |

| Provide guidance in the development, presentation and dissemination of DNP project | • Close mentorship and guidance during the development, implementation and reporting of students' DNP project is critical to student success | • Introduce writing workshops early in DNP programme and offer support for both analytical and writing skills and access to editorial support • Provide guidelines and template for construction and reporting of DNP projects • Encourage publication and dissemination |

| Follow-up with students after graduation to determine if they are continuing in leadership and process improvement roles | • Determine whether DNP programmes and their involvement in DNP projects has an impact on their career progression and involvement in process improvement | • Collaborate with graduates to determine their roles in leadership and process improvement in their work environment • Engage in a process of continual quality improvement in course design |

| Follow-up with students after graduation to determine the extent to which they have been productive in publishing work after their DNP project findings | • Dissemination of scholarly projects contributes best practice processes and outcomes which other sites and DNP students can replicate or build upon for future improvements | • Encourage faculty to assist students by taking a more substantive role in developing & submitting manuscripts from the DNP project • Develop contracts for dissemination of information |

6 |. CONCLUSION

Our review has found that process improvement, clinician development, patient safety, patient outcome improvement, access to care and workplace environment were a key focus of projects underscoring the relevance of the practice-focused degree. Ensuring graduates of clinical doctorates have the knowledge, skills and competencies for practice development is of critical importance. Ensuring that the capstone project demonstrates these attributes is essential for programme rigour.

7 |. RELEVANCE TO CLINICAL PRACTICE

DNP scholarly projects are a critical component of DNP curriculum in order to prepare nurses in advanced nursing practice to influence health care outcomes at the individual or population level. Therefore, evaluation of DNP scholarly projects is essential to improving DNP curriculum and ensuring DNP graduates are prepared to lead change in complex healthcare delivery systems. The findings from this descriptive study will provide insight to faculty at other schools with DNP programmes on ways to improve DNP projects that may lead to greater impact on clinical practice.

Supplementary Material

What does this paper contribute to the wider global clinical community?

Outlines the importance of programme evaluation in professional doctorate programmes

Profiles the challenges and opportunities for developing and refining a project aligned with delineated competencies

Provides recommendations for achieving methodological rigour and programme efficiencies

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge Denise Rucker, Academic Administrator for the DNP programme, for providing the DNP project report documents to review for this paper.

Funding

This study was supported in part by a grant from the Maryland Higher Education Commission (NSP II-17-107). RT is supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) of the National Institutes of Health under award number T32DK062707 and an award by the American Heart Association. ES is supported by the National Institute of Nursing Research of the National Institutes of Health under award numbers F31DR017328 and T32 NR012704.

Sponsors had no involvement in the study design; collection, analysis and interpretation of the data; in writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Footnotes

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information may be found online in the Supporting Information section.

Relevance to clinical practice: Programme evaluation is critical in order to sufficiently prepare nurses in advanced nursing practice to influence healthcare outcomes at the individual or population level.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None.

REFERENCES

- American Association of Colleges of Nursing (2006). The essentials for doctoral education for advanced nursing practice. Retrieved from https://www.aacnnursing.org/Portals/42/Publications/DNPEssentials.pdf

- American Association of Colleges of Nursing (2015). The doctor of nursing practice: Current issues and clarifying recommendations: Report from the task force on the implementation of the DNP. Retrieved from https://www.aacnnursing.org/Portals/42/News/White-Papers/DNP-Implementation-TF-Report-8-15.pdf?ver=2017-10-18-151758-700

- American Association of Colleges of Nursing (2018). Defining scholarship for academic nursing: Task force consensus position statement. Retrieved from https://www.aacnnursing.org/Portals/42/News/Position-Statements/Defining-Scholarship.pdf

- Becker KD, Johnson S, Rucker D, & Finnell DS (2018). Dissemination of scholarship across eight cohorts of doctor of nursing practice students. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 27(7–8), e1395–e1401. 10.1111/jocn.14237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer N. (2011a, September 27). Observational research designs. Lecture conducted from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Brewer N. (2011b, November 2). True and Pre-Experimental Designs for Evaluation. Lecture conducted from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Brewer N. (2011c, November 8). Quasi-Experimental Study Designs. Lecture conducted from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Brown MA, & Crabtree K. (2013). The development of practice scholarship in DNP programs: A paradigm shift. Journal of Professional Nursing, 29(6), 330–337. 10.1016/j.profnurs.2013.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey M, O’ Leary D, & Coghlan D. (2018). Unpacking action research and implementation science: Implications for nursing. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 74(5), 1051–1058. 10.1111/jan.13494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2009). Program collaboration and service integration: Enhancing the prevention and control of HIV/AIDS, viral hepatitis, sexually transmitted diseases, and tuberculosis in the United States. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/programintegration/docs/207181-c_nchhstp_pcsi-whitepaper-508c.pdf [Google Scholar]

- CFIR. Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (2019).Retrieved from https://cfirguide.org/

- CGS (2006). Professional master’s education: A CGS guide to establishing programs. Washington, DC: CGS. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Graduate Schools in the United States. (2007). Task Force Report on the Professional Doctorate. Washington, DC: Council of Graduate Schools. [Google Scholar]

- Cygan HR, & Reed M. (2019). DNP and PhD scholarship: Making a case for collaboration. Journal of Professional Nursing, 35(5), 353–357. 10.1016/j.profnurs.2019.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang D, & Dearholt S. (2017). Johns Hopkins University nursing evidence-based practice: Model and guidelines (3rd ed.). Indianapolis, IN: Sigma Theta Tau International. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Education, Science, and Training (1997). Research-coursework Doctoral Programs in Australian Universities. Australia: Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service. [Google Scholar]

- Dinapoli CM (2015). Improving continuous positive airway pressure adherence among adults. Journal of Nursing Education and Practice, 5(2), 110. 10.5430/jnep.v5n2p110 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dols JD, Hernandez C, & Miles H. (2017). The DNP project: Quandaries for nursing schools. Nursing Outlook, 65(1), 84–93. 10.1016/j.outlook.2016.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Embree JL, Meek J, & Ebright P. (2018). Voices of chief nursing executives informing a doctor of nursing practice program. Journal of Professional Nursing, 34(1), 12–15. 10.1016/j.profnurs.2017.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulton J, Kuit J, Sanders G, & Smith P. (2012). The role of the professional doctorate in developing professional practice. Journal of Nursing Management, 20(1), 130–139. 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2011.01345.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham ID, Logan J, Harrison MB, Straus SE, Tetroe J, Caswell W, & Robinson N. (2006). Lost in knowledge translation: Time for a map? Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions, 26(1), 13–24. 10.1002/chp.47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grove SK, Burns N, & Gray JR (eds.) (2013). Selecting a quantitative research design. In The practice of nursing research: Appraisal, synthesis, and generation of evidence (7th ed., pp. 214–263). St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders. [Google Scholar]

- Howard PB, & Williams TE (2017). An academic-practice partnership to advance DNP education and practice. Journal of Professional Nursing, 33(2), 86–94. 10.1016/j.profnurs.2016.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane RL (1999). A new model of chronic care. Generations: Journal of the American Society on Aging, 23(2), 35–37. [Google Scholar]

- Kim-Saechao SJ, Almario E, & Rubin ZA (2016). A novel infection prevention approach: Leveraging a mandatory electronic communication tool to decrease peripherally inserted central catheter infections, complications, and cost. American Journal of Infection Control, 44(11), 1335–1345. 10.1016/j.ajic.2016.03.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick JM, & Weaver T. (2013). The doctor of nursing practice capstone project: Consensus or confusion? Journal of Nursing Education, 52(8), 435–441. 10.3928/01484834-20130722-01 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan J, & Graham ID (1998). Toward a comprehensive interdisciplinary model of health care research use. Science Communication, 20(2), 227–246. 10.1177/1075547098020002004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mellors-Bourne R, Robinson C, & Metcalfe J. (2016). Provision of professional doctorates in English HE Institutions. Cambridge: Careers Research and Advisory Centre. Retrieved from http://hdl.voced.edu.au/10707/393040. [Google Scholar]

- Minnick AF, Kleinpell R, & Allison TL (2019). Reports of three organizations’ members about doctor of nursing practice project experiences and outcomes. Nursing Outlook, 67(6), 671–679. 10.1016/j.outlook.2019.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton S, & Fralic M. (2015). Interhospital transfer center model: Components, themes, and design elements. Air Medical Journal, 34(4), 207–212. 10.1016/j.amj.2015.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogrinc G, Davies L, Goodman D, Batalden P, Davidoff F, & Stevens D. (2016). SQUIRE 2.0 (Standards for QUality Improvement Reporting Excellence): Revised publication guidelines from a detailed consensus process. BMJ: Quality and Safety, 25(12), 986–992. 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettigrew A, & Whipp R. (1992). Managing change and corporate performance. In Cool K, Neven DJ, & Walter I. (Eds.), European industrial restructuring in the 1990s (pp. 200–227). Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Macmillan Academic and Professional. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers EM (1962). Diffusion of innovations (1st ed.). New York, NY: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Roush K, & Tesoro M. (2018). An examination of the rigor and value of final scholarly projects completed by DNP nursing students. Journal of Professional Nursing, 34(6), 437–443. 10.1016/j.profnurs.2018.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigma Theta Tau (n.d.). Sigma Theta Tau Virginia Henderson Repository.Retrieved from https://www.sigmarepository.org/.

- Singleton RA Jr, & Straits BC (2010). Approaches to social research (5th ed.). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Southard EP, Neufeld JD, & Laws S. (2014). Telemental health evaluations enhance access and efficiency in a critical access hospital emergency department. Telemedicine and e-Health, 20(7), 664–668. 10.1089/tmj.2013.0257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan NJ, Duval-Arnould J, Twilley M, Smith SP, Aksamit D, Boone-Guercio P, … Hunt EA (2015). Simulation exercise to improve retention of cardiopulmonary resuscitation priorities for in-hospital cardiac arrests: A randomized controlled trial. Resuscitation, 86, 6–13. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2014.10.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun GH, & Cherry B. (2019). Using the logic model framework to standardize quality and rigor in the DNP project. Nurse Educator, 44(4), 183–186. 10.1097/NNE.0000000000000599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terhaar M, & Sylvia M. (2015). Scholarly work products of the doctor of nursing practice: One approach to evaluating scholarship, rigor and impact on quality. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 25, 163–174. 10.1111/jocn.13113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldrop J, Caruso D, Fuchs MA, & Hypes K. (2014). EC as PIE: Five criteria for executing a successful DNP final project. Journal of Professional Nursing, 30(4), 300–306. 10.1016/j.profnurs.2014.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yam BM (2005). Professional doctorate and professional nursing practice. Nurse Education Today, 25(7), 564–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Younan LA, & Fralic MF (2013). Using “best-fit” interventions to improve the nursing intershift handoff process at a medical center in Lebanon. The Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety, 39(10), 460–467. 10.1016/S1553-7250(13)39059-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.