We read with great interest an article by Ji-Young Min and colleagues documenting the simultaneous administration of adjuvanted recombinant zoster vaccine (RZV) and the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV) in adults aged ≥50 years.1 Their results suggest that adults may benefit from receiving RZV and a PCV at the same healthcare visit. We would like to provide additional context for the implications of those conclusions by sharing results of a study we conducted to describe trends in invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) incidence among LA County residents for six respiratory seasons from 2015 to 16 to 2020–21.

Los Angeles (LA) County recorded its first case of COVID-19 in January 2020 and implemented non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs), such as wearing face masks and social distancing, to mitigate community transmission beginning in March 2020.2 Similar to the overall U.S. population, LA County experienced a reduction in circulating influenza and other viral respiratory pathogens after widespread implementation of NPIs.3 , 4 Since Streptococcus pneumoniae is a respiratory pathogen that is also transmitted via contact with respiratory droplets, we hypothesized that implementation of COVID-19 related control measures would be associated with similar reductions in IPD incidence.

The LA County Department of Public Health (DPH) conducts surveillance for 10 million residents across 86 cities (excluding the cities of Long Beach and Pasadena). Healthcare providers and clinical laboratories are mandated to report IPD cases to DPH.5 A confirmed IPD case is defined as the isolation of S. pneumoniae from a normally sterile body site (e.g., blood or cerebrospinal fluid) in a resident of LA County. All reported cases are investigated by DPH to determine if they meet the case definition. The COVID-19 pandemic required DPH to redirect staff to support the local response so no additional follow-up was conducted on IPD reports with incomplete information. Therefore, we established a probable IPD case definition for reports that occurred after January 1, 2020 and lacked sufficient information to establish if the confirmed case definition was met.

All reported cases are entered into a local surveillance data management system. We analyzed data by respiratory seasons, defined as July to June of the following year. The date of IPD cases’ occurrence was calculated from the earliest of symptom onset date, specimen collection date, specimen result date, date of diagnosis, date report is received by public health department, or the date the case is added to the surveillance database. We described cases by age, sex, and race/ethnicity based on information included in the case reports to DPH. We were able to directly compare groups without statistical testing since we were analyzing a complete data set of all reported IPD cases in LA County.

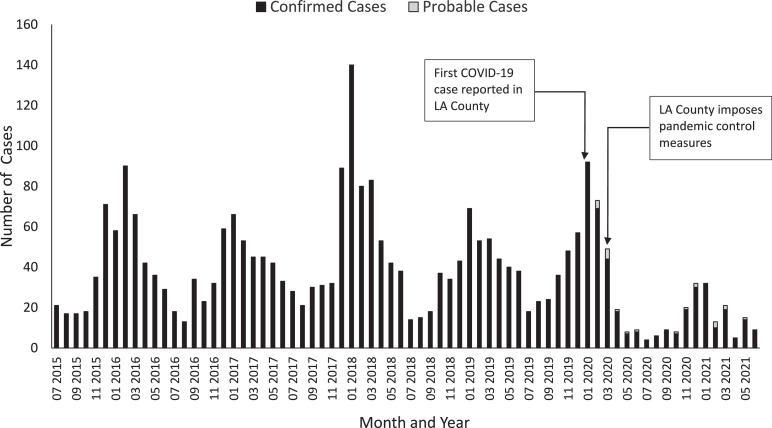

During the 2015–16 through 2018–19 seasons (Fig. 1 ), 2089 confirmed IPD cases were reported to DPH (median cases/year: 482; minimum: 463, maximum: 667). During the 2019–20 and 2020–21 respiratory seasons, 456 and 174 confirmed/probable IPD cases were reported, respectively. Among 2719 LA County residents with confirmed/probable IPD across all seasons (Table 1 ), the median age was 60 years (1st quartile: 46, 3rd quartile: 74), 1549 (57%) were male, 694 (26%) were Hispanic, 752 (28%) were White, 460 (17%) were Black, and 411 (15%) were unknown. The characteristics of IPD cases by age, sex, and race/ethnicity were similar across all seasons.

Fig. 1.

Confirmed and probable invasive pneumococcal disease cases reported in Los Angeles (LA) County from July 2015 to June 2021.1

Table 1.

Demographics of Persons with Invasive Pneumococcal Disease Reported in Los Angeles (LA) County from July 2015 to June 2021.

| Overall | July 2015 – | July 2016 – | July 2017 – | July 2018 – | July 2019 – | July 2020 – | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jun-16 | Jun-17 | Jun-18 | Jun-19 | June 20201 | June 20211 | |||||||||

| Total, N | 2719 | 500 | 463 | 667 | 459 | 456 | 174 | |||||||

| Age (years), median (Q1,Q3) | 60 | (46,74) | 61 | (48,75) | 60 | (45,74) | 61 | (48,75) | 61 | (45,74) | 61 | (45,72) | 58 | (45,69) |

| Age group (years), n (%) | ||||||||||||||

| <5 | 121 | 4% | 21 | 4% | 28 | 6% | 29 | 4% | 18 | 4% | 22 | 5% | 3 | 2% |

| 5–17 | 90 | 3% | 19 | 4% | 17 | 4% | 18 | 3% | 15 | 3% | 19 | 4% | 2 | 1% |

| 18–44 | 416 | 15% | 72 | 14% | 67 | 14% | 89 | 13% | 81 | 18% | 72 | 16% | 35 | 20% |

| 45–64 | 959 | 35% | 176 | 35% | 154 | 33% | 254 | 38% | 142 | 31% | 157 | 34% | 76 | 44% |

| ≥65 years | 1129 | 42% | 211 | 42% | 196 | 42% | 277 | 42% | 202 | 44% | 185 | 41% | 58 | 33% |

| Missing | 4 | 0% | 1 | 0% | 1 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 1 | 0% | 1 | 0% | 0 | 0% |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||||||||||||

| Female | 1154 | 42% | 209 | 42% | 194 | 42% | 283 | 42% | 220 | 48% | 186 | 41% | 62 | 36% |

| Male | 1549 | 57% | 290 | 58% | 269 | 58% | 384 | 58% | 238 | 52% | 260 | 57% | 108 | 62% |

| Missing | 16 | 1% | 1 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 1 | 0% | 10 | 2% | 4 | 2% |

| Race/Ethnicity, n (%) | ||||||||||||||

| Asian | 136 | 5% | 14 | 3% | 40 | 9% | 30 | 4% | 25 | 5% | 21 | 5% | 6 | 3% |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 460 | 17% | 79 | 16% | 69 | 15% | 112 | 17% | 92 | 20% | 80 | 18% | 28 | 16% |

| Hispanic | 694 | 26% | 107 | 21% | 132 | 29% | 158 | 24% | 127 | 28% | 115 | 25% | 55 | 32% |

| Non-Hispanic White | 752 | 28% | 130 | 26% | 117 | 25% | 204 | 31% | 138 | 30% | 124 | 27% | 39 | 22% |

| Other | 266 | 10% | 12 | 2% | 39 | 8% | 73 | 11% | 50 | 11% | 67 | 15% | 25 | 14% |

| Missing | 411 | 15% | 158 | 32% | 66 | 14% | 90 | 13% | 27 | 6% | 49 | 11% | 21 | 12% |

Abbreviations: Q1, first quartile; Q3, third quartile.

A confirmed case is defined as the isolation of Streptococcus pneumoniae from a normally sterile body site (e.g., blood or cerebrospinal fluid) in a resident of LA County. All reported cases are investigated by DPH to determine if they meet the case definition. A probable case lacked sufficient information to establish if the confirmed case definition was met. There were 11 probable cases in the 2019–2020 season and 10 probable cases in the 2020–2021 respiratory season.

We described trends in IPD among LA County residents during six respiratory seasons from 2015 to 16 to 2019–21. Corresponding with the introduction and widespread transmission of COVID-19 in 2020, the number of IPD cases declined from the 2019–20 season to the 2020–21 season. The reduction in IPD incidence during the COVID-19 pandemic has been observed in other regions of the world. Compared with the 2018–19 season, IPD incidence during the 2019–20 respiratory season in the United Kingdom was 30% lower.6 In Hong Kong, where strict social control measures were put in place with near universal masking, IPD cases decreased by 74.7% during 2020 compared with the comparable pre-pandemic period of 2015–2019.7 Conversely, IPD incidence increased after relaxing social control measures. In Switzerland, IPD incidence decreased by 73% from February to April 2020, remained low from April 2020 to February 2021, and then increased by 23% from March to May 2021 when social control measures were lifted.8

The decline in IPD cases associated with the COVID-19 pandemic is likely multifactorial. Public health recommendations/mandates for wearing facemasks, social distancing, and increased hand hygiene likely contributed to reduced transmission by decreasing the risk of coming into contact with respiratory droplets from someone with pneumococcal colonization. Moreover, school age children have a higher prevalence of pneumococcal colonization compared with adults, and they are an important source of transmission to adults in their household and community. Therefore, closure of LA County schools and childcare centers during the early part of 2021 likely resulted in decreased community transmission of S. pneumoniae.9 Finally, influenza activity declined substantially after the implementation of pandemic control measures; influenza activity was non-existent during the 2020–21 season.10 As a result, it is possible that there were fewer IPD cases as a secondary complication of influenza infection.

Our analysis is limited by the fact we relied on a passive surveillance system. As a result, cases will not be reported if people were less likely to seek care or get tested for IPD during the pandemic. Under ascertainment of cases during the pandemic is unlikely, however, because IPD tends to be a serious illness and most people will present for medical attention. Therefore, the magnitude of the reduction in IPD incidence during the pandemic cannot be fully explained by differential health seeking behavior alone.

Additional analysis is necessary to determine the precise contribution of the various pandemic control measures to the overall reduction in incidence of IPD and other respiratory pathogens. At a minimum, persons at high risk for IPD should consider wearing a facemask when in public spaces even after pandemic control measures are lifted given the evidence for the protection they confer from respiratory infections.

Declaration of Competing Interest

None of the authors have any relevant conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Min J.Y., Mwakingwe-Omari A., Riley M., Molo L.Y., Soni J., Girard G., et al. The adjuvanted recombinant zoster vaccine co-administered with the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in adults ages ≥50 years: a randomized trial. J Infect. 2022;84(4):490–498. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2021.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Los Angeles County Department of Public Health [Internet]. Los Angeles (CA): LA county daily COVID-19 data. c2000-2002 – [cited 2022 Jan 24]. Available from: http://publichealth.lacounty.gov/media/coronavirus/data/.

- 3.Los Angeles County Department of Public Health [Internet]. Los Angeles (CA): influenza in Los Angeles county. c2003-2021 – [cited 2022 Jan 24]. Available from: http://publichealth.lacounty.gov/acd/FluData.htm.

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National center for immunization and respiratory diseases [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): flu view: past weekly surveillance reports. c1999-2022 – [cited 2022 Jan 24]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/weekly/pastreports.htm.

- 5.publichealth.lacounty.gov/acdc/ [Internet]. Los Angeles Department of public health acute communicable disease control program; c2022 [cited 2022 Jan 24]. Available from: http://publichealth.lacounty.gov/acd/.

- 6.Amin-Chowdhury A., Aiano F., Mensah A., Sheppard C.L., Litt D., Fry N.K., et al. Impact of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic on invasive pneumococcal disease and risk of pneumococcal coinfection with severe acute respiratory syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV2): prospective national cohort study, England. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;72(5):e65–e75. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fok K.M.N., Lin K.P., Chan E., Ma Y., Lau S.K.P., et al. Substantial decline in invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) during COVID-19 pandemic in Hong Kong. Clin Infect Dis. 2022;74(2):335–338. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Casanova C., Küffer M., Leib S.L., Hilty M. Re-emergence of invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) and increase of serotype 23B after easing of COVID-19 measures, Switzerland, 2021. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2021;10(1):2202–2204. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2021.2000892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bogaert D., Groot R., Hermans P.W.M. Streptococcus pneumoniae colonization: the key to pneumococcal disease. Lancet. 2004;4(3):144–154. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(04)00938-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Los Angeles County Department of Public Health [Internet]. Los Angeles (CA): influenza in Los Angeles county. c2003-2021 – [cited 2022 Jan 24]. Available from: http://publichealth.lacounty.gov/acd/FluData.htm.