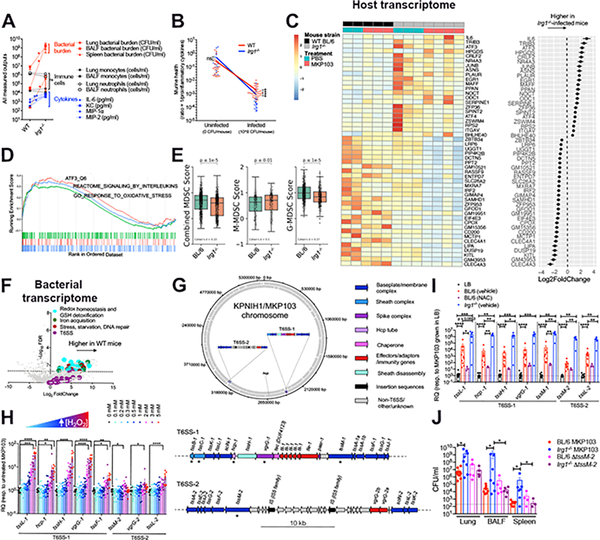

Figure 4. Itaconate dictates both host and pathogen responses during MKP103 infection.

(A) Bacterial burden and host immune cells and cytokines from the airway of WT BL/6 or Irg1−/−-infected mice (at 48 h pi), n = 10 mice and 8 mice respectively (from 3 independent experiments). Statistical analysis was performed by Mann Whitney non-parametric U-test, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. ***P < 0.001.

(B) Murine health (inversely proportional to proinflammatory cytokine levels) plotted against infection state. The slope of the curves indicates stronger disease tolerance in WT versus Irg1−/−-infected mice. Statistical analysis was performed by Mann Whitney non-parametric U-test, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. ***P < 0.001.

(C) Heatmap showing top 50 differentially expressed murine genes (Padj < 10−4, ordered by effect size) between infected WT and Irg1−/− mice (48 h pi), with each gene also normalized for basal expression in the respective uninfected mice (n = 2 uninfected and 3 infected WT BL/6 mice versus 3 uninfected and 4 infected Irg1−/− mice, 1 experiment). Biological replicates are adjacently grouped. The accompanying dot plot (right of heatmap) shows the direction and magnitude of expression change in infected Irg1−/− versus WT mice as log2-transformed fold change ± SEM.

(D) Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) of ranked genes from (C) against KEGG and GO gene sets involved in atf3-mediated (orange) or oxidative (green) stress responses and interleukin production (blue). The top portion plots the enrichment scores for each gene.

(E) Combined and stratified M/G-MDSC score plots for MKP103-infected BL/6 and Irg1−/−mice (n = 1 mouse per condition).

(F) Volcano plot of bacterial transcriptome displaying the pattern of gene expression values from MKP103 isolated from WT BL/6 mice (n = 3 mice, 1 experiment) at 48 h pi relative to in vitro LB culture (n = 3 biological replicates, 1 experiment). Significantly differentially expressed genes (FDR-corrected P≤ 0.05) are shown above the dotted line. Selected genes related to oxidative stress detoxification (cyan), iron acquisition (green), stress and repair (maroon) and T6SS (purple) are indicated.

(G) Schematic diagram showing the distribution of T6SS genes in the chromosome of KPNIH1, the parental strain of MKP103. The top panel shows the position and orientation of T6SS genes in the KPNIH1/MKP103 chromosome. The bottom panel shows both of these loci in detail; all T6SS-associated genes are annotated and the asterisk (*) indicates the T6SS genes of interest that were initially used to identify each of these regions. Genes are colored according to their role in T6SS. This figure was made using DNAplotter (Carver et al., 2009) in R (v3.6.0) using the R package genoplotR (v0.8.10) (Guy et al., 2010).

(H-I) Expression of T6SS genes from MKP103 (H) grown in increasing concentrations of H2O2 in LB, n = 10 biological samples per condition from 4 independent experiments or (I) harvested directly from the lungs of infected-WT BL/6 mice (48 h pi) treated (n = 10 biological samples from 3 independent experiments) or untreated with NAC (n = 3 biological samples from 1 experiment) and infected-Irg1−/− mice (n = 5 biological samples from 2 independent experiments), by qRT-PCR. RQ, relative quantification to MKP103 grown in LB only. For (H-I), columns represent mean values ± SEM, statistical analysis was performed by one-way ANOVA for each condition; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ***P < 0.0001.

(J) Bacterial burden (WT MKP103 or ΔtssM-2) from the lung, BALF and spleen of WT and Irg1−/− mice (n = 9 BL/6 mice infected with WT MKP103, n = 5 BL/6 mice infected with the ΔtssM-2 mutant, n = 8 Irg1−/− mice infected with WT MKP103 and n = 5 Irg1−/− mice infected with the ΔtssM-2 mutant, 2 independent experiments), at 48 h pi, *P < 0.05 by Mann Whitney non-parametric U-test.