Abstract

The Covid-19 pandemic has revealed the importance of social protection systems, including income security, when health problems arise. The aims of this study are to compare the follow-up regimes for sick-listed employees across nine European countries, and to conduct a qualitative assessment of the differences with respect to burden and responsibility sharing between the social protection system, employers and employees. The tendency highlighted is that countries with shorter employer periods of sick-pay typically have stricter follow-up responsibility for employers because, in practice, they become gatekeepers of the public sickness benefit scheme. In Germany and the UK, employers have few requirements for follow-up compared with the Nordic countries because they bear most of the costs of sickness absence themselves. The same applies in Iceland, where employers carry most of the costs and have no obligation to follow up sick-listed employees. The situation in the Netherlands is paradoxical: employers have strict obligations in the follow-up regime even though they cover all the costs of the sick-leave themselves. During the pandemic, the majority of countries have adjusted their sick-pay system and increased coverage to reduce the risk of spreading Covid-19 because employees are going to work sick or when they should self-quarantine, except for the Netherlands and Belgium, which considered that the current schemes were already sufficient to reduce that risk.

Key words: sickness absenteeism, sickness benefit, sick-pay, comparative study, European countries

1. Introduction

The vast majority of Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries have statutory paid sick-leave systems ([32], p. 3). However, national sick-pay policies vary enormously across countries and much could be learned from comparative research. Comparing sick-leave rates is a complex task that requires a clear understanding of the interplay between statutory, corporate and private forms of income protection during sickness absence ([12], p. 1101) Furthermore, international comparisons of sickness absence rates have long been extremely difficult because there are substantial differences in the legitimation of work incapacity, level of sick-pay and criteria for transfer to invalidity insurance ([31], p. 536).

Some early studies that used data from the Luxembourg Employment Study are available. For example, it was reported that many of the differences in the total rates of sickness absence between 11 European countries were not explained by the distribution of the characteristics of sex, age and skill level ([5], p. 26). It was also found that the sex difference in absence rates resulted from differences in the age structures of the male and female workforce and their marital status ([3], p. 325).

Studies using data from the European Working Conditions Surveys provide additional results. One of the first studies noted that before any clear comparisons can be drawn, data from EU countries must first be made comparable in terms of the definition of sickness absence (harmonising), which should be established by changes in sickness absence legislation in the different countries ([18], p. 869). Elsewhere, it was noted that the number of absence days was not influenced by employment protection, absenteeism was increased by sickness benefits and the impact of the institutional framework was lower than that of some individual worker characteristics ([16], p. 505).

Some studies using the European Union Statistics on Income and Living Conditions provide general findings about the different welfare state regimes. One study compared 26 European countries and found lower absolute and relative social inequalities in sickness in comprehensive welfare states and more favourable general rates of non-employment [39]. Thus, welfare resources appear to be more important than welfare disincentives with respect to sickness. Moreover, the welfare regime in Scandinavian countries is more able than others to protect against non-employment when individuals are faced with illness; this is particularly true for those with low educational levels [40]. In general, systems that activate rather than focus only on income protection are found to have better gatekeeping towards disability pensions [1,2].

The European economic literature on sickness absence stresses the importance of employment and adequate working conditions for the health of workers and labour market policies that focus on job sustainability and job satisfaction ([4], p. 693). A recent review of the literature and analysis of EU Labour Force Survey data from 13 European countries concluded that the essential problem of sick-pay insurance is one of moral hazard, given that health is largely continuous and non-observable ([30], p. 104).

A key report from the EU Commission shows that sick-pay schemes have changed in almost all EU countries over the last 20 years; most have changed in the direction of fewer rights for employees in the form of waiting periods, lower coverage and shorter periods that provide sick-pay rights [37].

Thus, cross-national comparative and collaborative research on sickness absence systems and statistics in Europe is desirable not only to advance knowledge about return-to-work policies and practices, but also to improve them ([19], p. 4). Detailed understanding of sickness benefit and sick-pay schemes is needed to elucidate cross-country differences in sick-leave rates. The schemes also involve legal obligations for different actors related to following up sick-listed employees, although these obligations are often overlooked in comparative studies, which hampers insight in how the burden of sickness is shared in different systems [3,8,20].

In the same way that patients diagnosed with a disease receive follow-up care, sick-listed employees are followed up by their employer, the health services and their insurance provider. However, the legislation for this follow-up differs across countries. The aim herein was to analyse these differences and similarities to gain knowledge about burden sharing between different system actors.

Here, we define each country's system—the regulations and formal obligations imposed on the involved actors—as the ‘follow-up regime’ for sick-listed employees. Although sickness absence management is a term that has previously been used for employers, it does not cover the obligations of the health services and insurance actors.

In recent years, several of the Nordic countries (Sweden, Denmark, Finland, Norway and Iceland) have implemented initiatives based on a close follow-up of sick-listed employees; our goal was to compare these regimes with those in other European countries. An examination of the follow-up regimes for sick-listed employees is warranted because the differences between these regimes can elucidate important explanations for the differences observed in the levels of sick-leave rates across countries. Initially, comparisons should focus on eligible salaried workers, who make up the largest proportion of the workforce [2,19]. We follow this recommendation because it would be much more complex to include the variation in regulations with respect to coverage eligibility for self-employed workers and unemployed persons.

The aims of this study are to present comparable components of the follow-up regime for sick-listed employees and to conduct a qualitative assessment of the differences with respect to burden and responsibility sharing between the social protection system, employers and employees. Sick-leave implies the right to be absent from work when sick, and return to work after recovery. In our analysis, we include both sickness benefits provided by the social protection system and sick-pay provided by the employer. We also describe the changes made in each country's system due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

2. Method

2.1. Comparative research

We describe sickness follow-up regimes in a group of high-income countries located in north-western Europe. This is a necessary first step towards an empirical study of a comparison of sickness absence rates and development of prediction models because ‘predictions cannot be made without well-founded theories; theories cannot be made without proper classification; and classification cannot be made without good description’ ([23], p. 21).

Because there are few comparative analyses of sickness absence rates other than the statistics provided by the OECD, qualitative descriptions of the different country regimes are required. We chose to focus on a small number of countries because it allows us to use less abstract concepts that are more grounded in the specific context under scrutiny [27]. Including relatively few countries also allows in-depth descriptions [38].

The selection of countries was based on the aim of comparing countries located in north-western Europe that share some cultural and labour market similarities, but that nevertheless differ with respect to their sickness absence policies.

2.2. Theoretical approach

Instead of focusing on describing all the differences between countries, we follow other social science scholars who have turned their attention to the study of parts of rather than the whole of society [11,28].

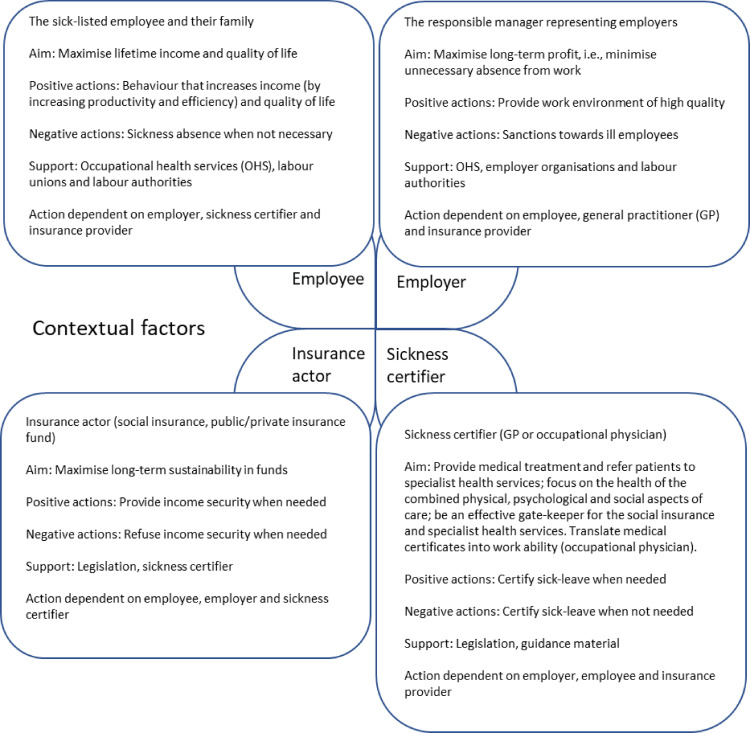

The relevant ANT phases in this study are: i) Identify the stakeholders, ii) Investigate the stakeholders, iii) Identify stakeholder interactions to explore the level og influence, iv) Construct an actor-network model ([9], p. 60). Instead of taking welfare regime theory as the starting point, we take a more direct approach by studying the main actors typically involved in a sickness absence incident: the employee, the employer and the health services, which is represented by the sickness certifier and insurance provider or actor (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Interdependent network of main actors in a sickness absence incident.

These actors co-operate to some degree in the follow-up of sick-listed employees. This actor perspective is used when we compare regimes across countries, following actor–network theory (ANT), where actors can be individuals, groups of individuals, institutions, boundary protocols, regulations and technical artefacts [24], [25], [26]. The employee may be the individual sick-listed person, the unions or other interest groups representing the sick-listed employee. The employer may be represented by management or the supervisor of the sick-listed employee or the employer organisations as interest groups. The health services may be represented by the general practitioner (GP), the occupational doctor or by a clinician in specialist health services or the health authorities. The insurance provider may be represented by a consultant from a private insurance company or by a counsellor from public services, depending on the system set-up. These actors are linked to each other in a system or network in which their relationships, incentives, beliefs, ethics and morals are interwoven in the functionality of the system. The aim of this study is not to model all the incentives embedded in the system or the behaviour of all these actors, but rather, to take a first step in studying their roles across different countries. The analysis was inspired by ANT, in that we look at how actors and actants—that is, the different human and non-human components of a sickness follow-up regime—work towards the goal of reducing unwarranted sickness absence by considering the strength of the incentives (inscriptions), or the force of the constituent non-human parts, towards achieving it. In this setting, the employee, the employer, the insurance actor and the sickness certifier operate in a non-hierarchical, complex network that produces or prevents unwarranted sickness absence via the follow-up regime. Inscriptions are the procedures or system requirements that indicate how the network of actors in the follow-up regime should operate (e.g. sick listing practices, employee contracts, documentation requirements).

The starting point of the description of the sickness follow-up regimes is sick-pay and sickness benefit schemes, which can be described by the criteria for qualification, namely the duration and economic compensation in the follow-up period of the employer and social insurance, respectively, and also by what happens if the person is still ill after the benefit is terminated.

Likewise, the sick-leave follow-up system can be described by the demands and roles of the actors during the follow-up, related to, for example, sick-leave certificates and formal contacts, including rules for partial sick-listing and reassessment, duties and responsibilities, support, sanctions and dismissals, and finally, the role of occupational health services (OHS) and others.

2.3. The nine countries studied

We included nine European countries in our study, representing a diversity of welfare regimes: Sweden, Denmark and Norway (the Scandinavian countries) and Iceland may be classified as pure-type social democratic welfare states, Finland as a social democracy with a Christian Democratic component, Belgium as a Christian Democratic welfare state with social democratic elements, Germany as a pure-type Christian Democratic welfare state, the UK as a liberal welfare state and the Netherlands as an unclassified hybrid welfare state [15].

2.4. Data collection

The Norwegian researchers initiated the study, invited and established the multidisciplinary team and developed 51 questions that were answered by the collaborators/experts/co-authors from each country. The topics were related to sickness benefits, sick-pay and the role and requirements for employers, employees, GPs, OHS and insurance providers in the follow-up regime.

There were many rounds back-and-forth to ensure that answers were comparable between countries, and all authors from each country contributed to ensuring that the tables containing the inscriptions were as accurate as possible. The answers produce both quantitative data (e.g. number of waiting days, maximum duration) and qualitative data (e.g. duties for the sick-listed employee and their employer).

2.5. Analyses

The first author facilitated a collaborative research process and all collaborators/co-authors contributed with input to each of the ANT-phases. A qualitative assessment of the follow-up regimes for each country was conducted. The components of the regimes are described and evaluated according to the strength of embedded incentives related to preventing and reducing the duration of sick-leave. We assess both the actors’ overall burden (economic and otherwise) and unintended consequences using abstract reasoning in which the context and bigger picture surrounding a sickness absence incident are examined. The aim of the analyses was to explore and identify discernible patterns based on the systematic overview of the detailed inscriptions collected ([23], p. 13).

3. Results

The results are summarised in Table 1 , which provides information on sick-leave benefits and sick-pay schemes. Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, Table 5 compare the features of the follow-up regimes across the nine countries. These tables constitute the ANT-based inscriptions.

Table 1.

Sick-leave benefits and sick-pay in the Nordic countries (Sweden, Denmark, Finland, Norway and Iceland) and in Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium and the UK.

| Denmark | Finland | Germany | Norway | Sweden | Netherlands | Iceland | Belgium | UK | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Different rules for different groups of employees | All employers receive a fixed amount in reimbursement, contracts may state that the employees are fully compensated a | No | No | No | No | Yes, sick-leave benefit depends on the type of employment contract | No | Yes, full pay for white-collar workers; less for blue-collar workers | Yes, all have the minimum Statutory Sick Pay, except those with low incomes, and company sick-pay schemes vary from employer to employer |

| Employer period | 30 days | 10 working days | 6 weeks | 16 calendar days | 14 calendar days | 2 years | 3–12 months | 7 days for blue-collar workers; 30 days for white-collar workers | 4 days–28 weeks |

| Compensation degree in employer period | Mostly 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 80% | 140%–200% for 2 years | 100% | 100% | Fixed amount per week |

| Compensation degree after employer period | Calculated from hourly wage | Depends on the level of income; low income gives higher compensation | 70% | 100% | 80% to day 364 and 75% thereafter | Not relevant, employer cover | 100% | Blue-collar employees receive 85% of pay from days 8 to 14, with further reductions for length of time; white-collar employees receive 100% | 0% but may be able to transfer to Employment and Support Allowance (ESA) |

| Maximum duration | 22 weeks in 9 months | 300 working days over 2 years for the same illness, not covering employer periods | 78 weeks over 3 years | 52 weeks | No upper limit if severe illness | 2 years | Depends on the contract | 1 year | 28 weeks |

| Diagnosis-dependent duration | More than 22 weeks granted if severe illness | No | Yes | No, but diagnosis-specific duration guidance to general practitioners (GPs) | No, but diagnosis-specific duration guidance to GPs | No | No | No | No |

| Waiting days | No | No | No | No | Yes, in practice, 1 day | Employer decides | No | No | Yes, 3 days |

| Individual contracts or collective agreements give better conditions | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Better conditions in contracts are common | Yes, public servants and many employees in the private sector receive 100% compensation | Yes, most employers pay 100% wage during the first 1–2 months or even longer, the sickness benefit in this case being paid to the employer | Yes | Yes, most employees earning more than a certain threshold income have employers who pay the difference | Yes | Yes, many employers pay 100% the first year and 70% the second year | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Qualification period | Worked 74 hours during the last 8 weeks/240 hours during the last 6 months | No, but a contract that has lasted for at least 1 month is required to get the full wage during the employer period | 4 weeks | 4 weeks | No, rights from the first day | No, rights from the first day | 4 weeks | 180 days of actual work during the 6 months prior to the invalidity | Must have an employment contract and have done some work |

| When still sick after maximal duration | May be entitled to work assessment benefit | May be entitled to temporary or permanent disability pension | May be entitled to unemployment benefit | May be entitled to work assessment benefit | No upper limit if severe illness | May be entitled to disability benefit | May be entitled to support from union funds and some from the State | May be entitled to invalidity benefit | May be entitled to ESA |

| Income tax* | 35.8 | 16.6 | 16.0 | 17.1 | 13.8 | 15.6 | 26.6 | 20.3 | 12.6 |

| Social security contributions paid by employer* | 0 | 17.6 | 16.2 | 11.5 | 23.9 | 10.4 | 6.3 | 21.3 | 9.8 |

| Social security contributions paid by the employee* | 0 | 8.1 | 17.3 | 7.3/8.1? | 5.3 | 11.6 | 0.3 | 11.0 | 8.5 |

| Total tax wedge* | 35.7 | 42.3 | 49.4 | 35.8 | 43.1 | 37.7 | 33.2 | 52.7 | 30.9 |

Income tax plus employee and employer social security contributions. Source OECD: Taxing Wages 2019: https://www.oecd.org/ctp/tax-policy/taxing-wages-20725124.htm

a: In practice, more blue-collar workers, freelancers and employees in precarious jobs do not have contracts that entitle them to full compensation. Some workers have full salary during sickness leave (in this case, the employer receives the benefit instead), whereas others receive benefits. The benefits are flat rate, but with the exception that the maximum pay is 85% of the full-time salary, meaning that many receive less than 85%. White-collar workers mostly have contracts with 100% salary during sickness leave; this is also the case for some blue-collar workers. The majority of workers on contracts without salary during sickness leave are blue-collar workers.

Table 2.

Follow-up legislation for people on sick-leave, sick-leave certification and formal contact in the Nordic countries (Sweden, Denmark, Finland, Norway and Iceland) and in Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium and the UK.

| Denmark | Finland | Germany | Norway | Sweden | The Netherlands | Iceland | Belgium | The UK | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sick-leave certificate from medical doctor required? | No, but employer can demand this after 3 days | Employer decides if needed in the first 10 working days; required after the employer period | Yes, after 3 days | Yes, after 3–8 days depending on the employer | Yes, after 7 days | No | No, but the employer can demand a certificate | Yes, within 2 working days, the employee must deliver a declaration of incapacity | Yes, if ill for >7 calendar days |

| Who can issue certificates? | Medical doctors only, usually general practitioners | Medical doctors only | Medical doctors, dentists and in some states, chiropractors and physiotherapists | Medical doctors, chiropractors and physiotherapists | Medical doctors and dentists | No sickness absence certification | Medical doctors | Medical doctors | Fit note issued by a medical doctor a |

| Qualifications about working life needed for issuing of sick-leave certification | Not required | Not required | Not required | Not required | Not required | No sick-leave certificates | Not required | Not required | Not required |

| Partial sick listing allowed? | Yes | Yes, after the employer period | Yes, after a long sick-leave incident | Yes, but not <20% sick-listed (counted as 100% in duration) | Yes, if work capacity is reduced by at least 25% | Yes, without limitations | Yes, but counted as 100% in duration | Yes | No |

| Can the employer dispute the sick-leave certificate? | No | Yes, the employer can ask for another doctor's opinion | Yes, the employer can ask for another doctor's opinion | Yes, the employer can send a letter to the Labour and Welfare Office and dispute the sick-leave | No | No, however, the legitimacy of the sick-leave is checked retrospectively | Yes, and the dispute can end up in court | Yes, the employer can use an independent medical officer, called a controller officer | Yes, Statutory Sick Pay is only payable if the employer decides that the reason is acceptable |

| Need for new assessment of health later in the sick-leave progress? | After 8 weeks, the municipality will demand a medical certificate (even if the employer received this earlier) | After receiving the sickness benefit for 60 working days, an extended certification of work disability must be delivered | No, other than renewal of a sick-leave certificate when the old one expires | After 8 weeks, a new medical certificate is required; this must show extensive health problems | Yes, in several steps. After the first 90 days, the work ability is reassessed in relation to the current position or another position for the same employer. After 180 days, the assessment is made in relation to ‘normally occurring work tasks on the labour market’. | Assessments are made when the situation changes b | When the employer asks for it | A new questionnaire is developed to decide whether to start a reintegration process | No |

| Communication from the system to the employee | It varies; job centres follow up individual cases | The system sends an information letter after receiving the sickness benefit for 60 and 150 working days | The system sends a message if coverage is granted after 6 weeks | The system sends a letter to the employee at week 8 and calls a meeting within 6 months | It varies; up to the caseworker | An occupational physician follows up the employee until week 92 c | After the employer period, the employee decides if they want contact | No | |

| Communication from the system to the employer | It varies; job centres follow up individual cases | Little, other than refunding wages beyond the employer period | Little, other than refunding wages beyond the employer period | The employer sends a follow-up plan to the GP and to the system. The system calls a meeting within 6 months, and refunds wages beyond the employer period | The caseworker can call a meeting with all partners and refund wages beyond the employer period | Close contact between the employer, employee and company doctor | No formal rules | No |

a: Also (if accepted by the employer) issued by osteopaths, chiropractors, Christian Scientists, herbalists, acupuncturists, etc.

b: The sickness absence legitimacy is checked by the occupational physician within 6 weeks and retrospectively after 2 years by the social insurance office (or earlier if the employer asks for a second opinion).

c: A disability benefit can then be applied for via the social insurance system.

Table 3.

Follow-up of sick-listed employees, duties and responsibilities in the Nordic countries (Sweden, Denmark, Finland, Norway and Iceland) and in Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium and the UK.

| Denmark | Finland | Germany | Norway | Sweden | The Netherlands | Iceland | Belgium | The UK | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duties for the sick-listed employee | Inform the employer about illness as soon as possible Try out work-related activities as soon as possible |

Inform the employer about illness as soon as possible Deliver sick-leave certificate Apply for sickness benefits within 2 months from the first day of absence Deliver an evaluation by the occupational health services (OHS) after receiving the sickness benefit for 90 working days |

Inform the employer about illness as soon as possible Try out work-related activities as soon as possible |

Inform the employer about illness as soon as possible Deliver sick-leave certificate after 3–8 days Try out work-related activities as soon as possible Participate in the planning for return to work (RTW) |

Inform the employer about illness as soon as possible Try out work-related activities as soon as possible Participate in the planning for RTW |

Inform the employer about illness as soon as possible Must co-operate with employer Participate in the planning for RTW |

Inform the employer about illness as soon as possible Deliver sick-leave certificate if employer asks |

Inform the employer about illness as soon as possible Deliver sick-leave certificate within 2 working days |

Inform the employer about illness as soon as possible Deliver evidence of illness to the employer if required |

| Duties for the employer | Wage payment Call a meeting with the employee |

Wage payment Notify OHS if sick-leave has lasted for 30 days Apply for sickness benefit for refunding wages within 2 months from the first day of absence |

Wage payment Call a meeting with the employee |

Wage payment Call a meeting with the employee Prepare a follow-up plan in co-operation with the employee within 4 weeks and send the plan to the general practitioner and Labour and Welfare Office (NAV) Participate in a dialogue meeting within 6 months organised by the NAV |

Wage payment Plan RTW Establish a mandatory rehabilitation plan at the latest 30 days from the first day of absence if absence is foreseen to last more than 60 days |

Wage payment Hire a certified occupational specialist within 6 weeks to analyse the problem that causes the sick-leave Establish a plan for reintegration within 8 weeks, including modifications and gradual RTW a |

No duties, the unions pay benefits after the employer period | Wage payment Health insurance |

Wage payment of Statutory Sick Pay (minimum requirement) Pay company sick-pay if contracted No duties, the employer decides how to monitor sickness absence |

| Meeting requirements | Yes, after 4 weeks, the employer must invite the employee to a meeting to discuss the situation and plan reintegration b | No meetings are required, but the 90-day evaluation by the OHS is made in collaboration with the employee and employer | Yes, if sick-listed for >6 weeks during a 12-month period, the employer must call a meeting to discuss the situation and plan reintegration c | Yes, the employer must call a dialogue meeting about the content of the follow-up plan within 7 weeks at the latest, unless this is clearly unnecessary | No meetings are required | Yes, within 6–8 weeks | No | No meetings are required | No meetings are required |

a: If the employee is not reintegrated after 1 year, the employer is obliged to offer a suitable job in another organisation (in practice, this is often facilitated by a reintegration agency).

b: After 8 weeks, the employee can ask for a plan to remain at his/her job with the employer.

c: The purpose of such a meeting is to discuss the way in which the workplace has influenced the absence of the employee and to determine whether the employer can make any changes and help to improve the employee's health.

Table 4.

Follow-up of sick-listed employees, support and dismissal in the Nordic countries (Sweden, Denmark, Finland, Norway and Iceland) and in Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium and the UK.

| Denmark | Finland | Germany | Norway | Sweden | The Netherlands | Iceland | Belgium | The UK | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dismissal of sick-listed possible? | Yes, but depends on the type of contract | Yes, but not only because of illness | Yes, but the employer must be certain that the employee will not get well | No | Yes, if the employer has done all they can to facilitate return to work (RTW) | No | Yes | No, it is prohibited to terminate the contract because of sickness a | Yes, if the employee cannot do his/her job and no reasonable adjustments can be made, it may be fair for the employer to dismiss the employee, even if disabled |

| Sanctions in the system? | Yes, the employer can send a warning to employees with extended sick-leave, and this can lead to dismissal | Yes, sick-pay can stop if the employee does not deliver the 90-day evaluation by the occupational health services (OHS), made in collaboration with the employee and employer | Yes, the employer can send a warning to employees with extended sick-leave, and this can lead to dismissal b | Yes, the employer can dispute the sick-leave | Yes, if the RTW plan is poor and not followed up, the caseworker can report the employer to the labour authorities | Yes, if the employer and employee do not comply with carrying out an evaluation (after 52 weeks and 2 years), they can be fined* | Yes, the employee can be dismissed | Yes, there are sanctions (suspension of salary) if the employee does not provide a medical certificate | Yes, the employee can be dismissed |

| Who assists the employer if the sick-leave is prolonged? | The job centre in the municipality | OHS and occupational rehabilitation actors | OHS and prevention companies | The local Labour and Welfare Office and the OHS or work centre | If the employee does not fulfil his/her responsibility, he/she can turn to the trade union. There is an opportunity to engage the Swedish Work Environment Authority if the problem is considered to be a structural one | Occupational physicians, whose main task is to translate the medical diagnosis into work ability. Only work ability information can be communicated with the employer to safeguard privacy | The employer can buy services from the private sector | Controlling doctors who can be sent by the employers to check the status of the sickness of employees at any moment | Different advice services are available to employers for consultation |

| What competence do these actors have? | Labour market competence, social work and occupational health | The OHS has occupational health competence, but occupational rehabilitation actors have varying competences | Various | Social security, labour market and health if OHS are available | Various | Translate the medical diagnosis into work ability | Not relevant | Medical doctors | Various |

| Does the system differentiate between work-related and non-work-related sickness absence? | No, no differentiation between ‘social risk’ and ‘occupational risk’. Occupational accidents are compensated from separate insurance | ||||||||

a: Dismissal of an employee with a permanent medical health condition will only be allowed if the occupational doctor confirms that the employee will never be able to perform any job within the company.

b: The employer has to go through a statutory process to determine the incapacity for work.

Table 5.

Follow-up of sick-listed employees, role of occupational health services (OHS) and other actors in the Nordic countries (Sweden, Denmark, Finland, Norway and Iceland) and in Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium and the UK.

| Denmark | Finland | Germany | Norway | Sweden | The Netherlands | Iceland | Belgium | The UK | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OHS legislation | Compulsory OHS was abandoned in 2009, and partly replaced by health insurance and risk-based inspections with a ‘smiley system’; the use of professional advisors can be imposed with identified deviations a | Employers are obliged to organise and finance preventive occupational health care. The costs are partly refunded from the Social Insurance Institution | Employers are obliged to associate occupational health and safety competence b | Compulsory OHS in many branches and compulsory approval for all OHS (employers are obliged to contract an OHS or have their own OHS) | OHS is not mandatory, but should be used when needed | Compulsory OHS (internal or external) whose main task is to translate the medical diagnosis into work ability. Only work ability information can be communicated with the employer to safeguard privacy | No obligations | Internal and external service for prevention and protection | The Management of Health and Safety at Work Regulations 1999 require employers to appoint ‘one or more competent persons’ to help them meet their duty to control risks at work |

| OHS role in preventing sickness absence | No clear role | OHS shall prevent work-related sick-leave and accidents and promote work capacity and functioning | The work environment is required not to strain employees on the basis of secure scientific findings. Employers have to prove this in a psychological and physical risk assessment | OHS is supposed to be an expert advisory service within preventive OHS work | No clear role | OHS should mainly take preventive actions and contribute to healthy workplaces and reduce injuries, sickness absenteeism and promote well-being in the workplace | Contract-based | Contract-based | Contract-based |

| Other actors’ roles in preventive work | Job centres follow up the sick-listed and suggest preventive measures in the workplace | Occupational rehabilitation is provided as a statutory right to prevent work disability | The insurance system can advise employers about prevention measures | A division of the Labour and Welfare Offices should work preventively | A new vocational category called ‘rehab coordinators’ has recently been introduced; however, the implementation differs throughout the country and the adequacy of this new category is debated | Indirectly c | Contract-based | Contract-based | Contract-based |

| Employer incentives to prevent sick-leave | No strong incentives; however, the employer is responsible for the work environment and should prevent sick-leave | Yes, because by collective agreements, most employers pay the full wage during the first 1–2 months or even longer d. In this case, however, the sickness benefit is paid to the employer | No, not for sick-leave lasting >6 weeks | No, not directly for sick-leave lasting >16 days, but there are significant indirect costs of long-term sick-leave | No, no strong incentives e | Yes, very strong incentives because the employer bears all the costs of sick-leave f | The employer can receive support from VIRK g concerning prevention measures | The employer is responsible for introducing a well-being policy in their enterprise | Strong incentives because they pay 4 days to 28 weeks of sick-leave |

a: The responsibility has been moved from the State to the employers, who decide how much effort they put in.

b: The Commercial OHS market has small and large actors, with requirements towards the extent and use of OHS for employers. Small firms can be compensated.

c: Yes, after 52 months and when applying for disability benefit, the social insurance checks whether the employer, employee and occupational physician have acted according to the Gatekeeper Improvement Act. Employers and employees can receive financial sanctions.

d: Large employers also have an incentive to prevent work disability because the amount of their pension insurance payments is determined by previous rates of disability retirement in the company.

e: Sick-pay from the employer was introduced at the beginning of the 1990s to provide incentives to prevent sick-leave.

f: In addition, through the mandatory involvement of occupational physicians in long-term sick-leave incidents.

g: VIRK is a rehabilitation fund established by employers.

Table 1 shows that four countries have different rules for different groups of employees (Denmark, Belgium, the Netherlands and the UK). In Denmark and Belgium, blue-collar workers are compensated more poorly than white-collar workers. In the Netherlands, the sickness benefits depend on the type of employment contract. In the UK, Statutory Sick Pay (SSP) is the same for all employees, while company sick-pay varies from employer to employer.

The employer period varies from 10 working days in Finland, 14 calendar days in Sweden and 16 in Norway to 2 years in the Netherlands. Finland, Germany, Norway, Iceland and Belgium provide 100% compensation in the employer period. In Denmark and the UK, a fixed amount per week is paid to all sick-listed employees, in Sweden, the sick-pay is 80% of the salary with a maximum amount per day, and in the Netherlands, 70% compensation is the minimum level.

There is considerable variation in compensation after the employer period, from 0% in the UK (no sickness benefits provided by the social protection system) to 100% in Norway for up to 52 weeks. The maximum period is longest in Sweden, where no upper limit is set in the case of severe illness.

Only the UK has waiting days in its scheme, while in the Netherlands, it is up to the employer or dependent on the social agreements with trade unions. In Sweden, the waiting day was replaced with a 20% deduction of sick-pay during an average work week on 1 January 2019.

Better conditions in individual contracts or collective agreements are common in all nine countries, while the qualification period varies from no period (rights are granted from the first day) in some of the countries to 4 weeks in Germany, Norway and Iceland.

The total tax wedge, that is, the income tax and social security contribution from employers and employees, is a measure of how much the government receives as a result of taxing the labour force. The tax wedge varies from 30.9% in the UK to 52.7% in Belgium. The total tax wedge is also high in Germany (49.5%), Sweden (43.1%) and Finland (42.3%). Denmark does not have social security contributions from employers and employees, and the income tax is therefore equal to the total tax wedge (35.7%).

Table 2 provides a comparison of sick-leave certification, partial sick-leave legislation and elements of the follow-up regimes. While the employer decides if a medical sick-leave certificate is needed in Denmark and Iceland, this is demanded after 3 days in Germany, 3–8 days in Norway and after 7 days in the UK. In the Netherlands, there is no requirement for sickness absence certification from a doctor at all, only self-certification where the employee reports sick to the employer and provides a reason for the sickness to the occupational physician. In most of the countries, the GP issues sick-leave certification. However, in Germany and Norway, chiropractors and physiotherapists can also issue sick notes, and in Sweden, also dentists. In Germany, sick-leave certification depends on the contract of the National Association of Statutory Health Insurance Physicians. In every German state, a dentist can issue a sick-leave certificate; in some states, this can be done by physiotherapists. None of the countries have a requirement concerning the qualifications about working life or labour market for the sick-leave certifiers.

Table 3 shows that the duties for employees are similar across the nine countries, and the employee must inform the employer about the sickness as soon as possible and deliver a sick-leave certificate if required. Four of the schemes also demand that the employee try out work-related activities as soon as possible (Denmark, Germany, Norway and Sweden). In Finland, the sick-listed employee must co-operate when the OHS assess the remaining work ability and the possibilities of returning to work, but there is no demand for the employee to try to return to work during the certified sick-leave period. The obligations for employers are especially detailed in Norway, Sweden and the Netherlands.

In the Netherlands, an extensive follow-up regime has been implemented, and the employer has considerable responsibility and covers all the costs during the first 2 years. Within 6 weeks of sick-leave, the employer is obliged to pay for a problem analysis of the sickness absence by a certified company doctor. Employers have contracts with occupational physicians or OHS take care of this duty. Within 8 weeks, the employer and employee must prepare a plan for the employee to return to work, and the plan can include work accommodations, interventions paid by the employer (e.g. counselling) and an updated return-to-work plan. If the employee is still on sick-leave after 1 year, the employer is allowed to try to offer the sick person another job at another organisation if their reinstatement in the original organisation is not possible; this is typically done by hiring a reintegration consultant. If the employee is not back to work after 2 years, a disability benefit can be applied for from the public social security system; this is only granted if the theoretical loss of earning capacity due to the disability is more than 35% of the former income.

Denmark has chosen a completely different model, in which municipal job centres are responsible for following up sick-listed employees. The employer still has obligations and must invite the sick person to a meeting to discuss the situation, and they must work out a plan for returning to work (reintegration). After 8 weeks, the employee can ask the employer for a plan to stay employed at the workplace. Also after 8 weeks, the job centre requires a medical statement regardless of whether the employer received one earlier. To be entitled to sickness benefits, the sick person must try out work-related activities as soon as possible, as proposed by the job centre. Employers in Denmark are expected to be in contact with the job centre from the municipality where the employee lives; in this way, each employer is likely to be in contact with several job centres.

From Table 4, we see that dismissal of sick-listed employees is strictly forbidden only in Norway and the Netherlands. In Belgium, dismissal is possible if it can be documented that the employee will not get well, and only then after it is confirmed by the occupational doctor that the employee would not be able to carry out any job in the company. In Germany, the employer has to go through a statutory process that determines the incapacity for work before dismissal. In Sweden, sick-leave alone is not reason enough for dismissal, but if the employee cannot do any work at all for his/her employer, the employer can terminate the contract. In Norway and the Netherlands, dismissal of sick-listed employees is only possible after 1 and 2 years of sick-leave, respectively.

Furthermore, all schemes seem to have some built-in sanctions. In Finland, sickness benefits can be stopped if the sick-listed employee fails to deliver the 90-day evaluation by the OHS, made in collaboration with the sick-listed employee and the employer. In Sweden, the employer can be reported to the labour authorities if the reintegration plan is of poor quality or not being followed. The strongest sanction of employees involves possible dismissal, as in Iceland, Denmark and the UK. A softer approach is taken in Norway, where the employer can dispute a sick note by writing a letter to the local Labour and Welfare Office, who will inspect the disputed sick-leave incident.

Table 5 shows that the requirements for OHS vary considerably. In Denmark, compulsory OHS were abandoned in 2009. By contrast, Norway has strengthened OHS legislation through compulsory approval of all OHS by the Labour Inspection Authority. The weakest demand for OHS appears to be in Denmark, Sweden, Iceland and the UK.

From the employer's perspective, the incentives to prevent sickness absence are especially strong in the Netherlands and the UK, where employers bear the whole burden of sickness absence. In the Netherlands, employers might additionally be punished by the social insurance system if they have not been compliant with sickness absence guidance legislation during the sickness absence period. The incentives are weakest in Norway and Sweden, which have the shortest employer periods.

4. Discussion

The results of this study highlight the different systems for following up sick-listed employees in the nine north-western European countries included. We are unaware of any other studies that have compared the follow-up regime for sick-listed employees between countries. Table 6 offers a rough categorisation of the follow-up regimes based on a qualitative assessment and conceptual reasoning of the results from the ANT inspired research process. The system requirements and the strength of incentives they provide for employees, employers and social insurance systems in each of the nine countries under study, constitue the ANT inscriptions assessed in the analysis.

Table 6.

Categorisation of the follow-up regimes in the nine countries.

| Country | Requirements for sick-listed employees | Reduction in compensation (degree and length) | Total employee burden | Requirements for employers | Length of employer period | Total employer burden | Social insurance system burden of sick-leave |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Denmark | High | Medium | High | Low | Short | Low | Medium |

| Finland | Medium | Low | Medium | Medium | Short | Medium | Medium |

| Germany | Medium | Medium | Medium | Low | Medium | Medium | Medium |

| Norway | Medium | Low | Medium | Medium | Short | Medium | Medium |

| Sweden | High | Low | Medium | High | Short | Medium | Medium |

| Iceland | Low | Medium | Low | Low | Medium | Medium | Medium |

| Belgium | Medium | Medium | Medium | Medium | Short | Medium | Medium |

| Netherlands | High | Medium | High | Very high | Long | High | Low |

| UK | High | High | High | Low | Long | High | Low |

The employee burden is based on a combination of factors such as the degree of compensation and the requirements for return-to-work activities. This burden is high in Denmark, Sweden, the Netherlands and the UK because of high requirements when sick-listed; because they receive less income compensation when sick, a higher burden is imposed on blue-collar than on white-collar workers in Denmark and Belgium. In the Netherlands, all workers receive 70%, or the minimum wage if 70% is lower than the minimum wage.

The employer burden depends on the length of the employer period and financial and other requirements for employers during the sick-leave period; these requirements are high in Sweden and the Netherlands. The length of the employer period is especially long in the Netherlands and the UK, of medium length in Germany and Iceland and relatively short in the other countries. The total employer burden is low in Denmark, high in the Netherlands and UK and at a medium level in the other countries.

The burden of sick-leave on the social insurance system is difficult to assess. If we do not consider differences in sick-leave rates, the burden on the social insurance system is lowest in the UK and the Netherlands because of the long employer period. Moreover, in the Netherlands, there is no social protection for the self-employed (12% of the working population), and only 20% of the self-employed have arranged private insurance [13]. However, it can be argued that high sick-leave rates, as in Norway, place a higher cumulative burden on the social insurance system.

We must also consider the utility or value of the current system for the working population, employers and social insurance system. Full income compensation may be more valuable for both the working population and employers who sell goods and services because income loss during a sickness absence is compensated, thus maintain purchasing power. The social insurance system might also benefit from full income compensation if it means that the shared risk implies higher employment and more taxpayers to share the costs.

It is recommended that appropriate rehabilitation and retaining measures, as well as a comprehensive prevention agenda, should underpin sickness benefit policies ([37], p. 4). Further, we suggest that the follow-up regimes should be included in future discussion of sickness benefit policies because components of these regimes can potentially be developed further and contribute to effective incentives for preventing sick-leave.

The ANT framework has been used in the field of disability studies [17]; sick-leave could be studied similarly. Disability is not a property of individuals only, because the degree of disability depends on the environment. The ANT perspective ‘seeks to reveal what is happening, how it is happening and what is involved in that which is happening’ ([36], p. 98). Sick-leave and return to work depend on the actions and behaviours of all participants (the sick-listed employee and his or her family, the employer, the insurance actor and the sickness certifier), and these interconnected complexes depend on the orientation of the current sickness benefit scheme and the social, historical and cultural context in which the sick-leave occurs [14,41]. Thus, if a theoretical approach were to guide the research, comparing sick-leave rates and sick-leave behaviour across countries is a much more complex task than simply comparing statistics.

International variation in sick-leave rates was previously found to be caused by factors such as ‘the generosity of granting sick-leave, the strictness of employment protection and the employment of older persons’ ([29], p. 97) and the extent to which activation measures supporting reintegration into work are incorporated [2]. Using data from the 2010 European Working Conditions Survey, one study found that the most significant factor for cross-country differences in the probability of absence is whether employers are required to continue paying full wages in case of illness, given that absences are significantly higher in countries where this rule applies [10]. Another study compared short-term sickness absences in 24 European countries and found a negative relationship between union density and sickness absence [35]. It was argued that a stronger collective employee voice would give rise to a lower short-term sickness absence, and that this perspective could provide new insights into why countries experience different trends in sickness absence over time. A study comparing cross-national sickness absence systems and statistics identified common elements in sick-leave in Spain, Sweden and the Netherlands [19], thereby concluding that basic and useful sick-leave indicators can be constructed to facilitate cross-country comparisons. Although we agree that it is possible to facilitate cross-country comparisons, we suggest that the system components in the different countries need to be understood in more detail, and that the share of economic burden must be included in comparisons, as this factor likely provides the strongest incentive for preventing sickness absence. It is not obvious that countries with the highest employer burden—and thus low sick-leave rates—have the best system if the main economic goal is to maximise employment rates.

Public schemes for sickness benefits often attract criticism because of the lack of incentive that they provide to employers for preventive and reintegration activities. Although employer incentives appear to lower sick-leave rates, the downside is that workers with poor health have fewer employment opportunities [21] or are sorted into temporary employment, as seen in the Netherlands [22] (see Supplementary Figures S1-1 and S1-2).

The relationship between the generosity of paid sick-leave and three economic indicators (per capital gross domestic product (GDP), unemployment rates and competitiveness) has also been examined. No significant relationship was found between the generosity of a country's sick-leave policy and these macroeconomic indicators [34].

Employment is a key concept as a measure of economic activity because GDP is a product of employment and productivity. Employment rates are typically measured as the proportion of working-age people who have worked for at least 1 hour in the reference week. However, information about the actual time worked by the employed during 1 year is lost in this simple head count and ignores the large variation in working time arrangements and job contract durations [6]. The full-time equivalent (FTE) employment rate is equivalent to the ratio of total actual hours worked if employed full time [7]. While Iceland has a high FTE employment rate among both men and women, the Netherlands and Belgium have low FTE employment rates, especially among women (see Supplementary Figure S2-1), and Denmark, Norway and Finland also have low FTE employment rates among men (see Supplementary Figure S2-2).

4.1. Changes in the systems due to the Covid-19 pandemic

According to the International Labour Organization (ILO), the Covid-19 crisis has revealed important gaps in the coverage of entitlements to social protection in case of sickness (ILO brief, May 2020). In March 2020, Sweden abolished the qualifying day of sickness because of Covid-19. In May 2020, the Danish Parliament passed a bill to amend the Sickness Benefit Act that would allow employees at higher risk of infection with Covid-19, as well as employees with a relative in a higher risk group, to receive sickness benefits. Similarly, the bill allows employers paying salaries during such absence to receive sickness benefit reimbursement from the first day of absence. In Finland, sickness allowance on account of an infectious disease provides loss-of-income compensation for persons placed in quarantine and isolation. Norway has waived the requirement for personal turn-out at the doctor's office to receive a sick note and reduced the employer period from 16 days to 4 days if the sick-leave incident is due to Covid-19 (infected, suspected infection, quarantine and isolation). Iceland also adjusted their system to slow the spread of Covid-19 by ensuring that individuals can follow official instructions to enter quarantine without having to worry about their personal finances. Germany also waived the requirement for personal turn-out to receive a sick note from the doctor. In the Netherlands, there have been no measures or amendments with respect to sick-pay, and the employer still has a statutory obligation to pay employees on sick-leave for up to 2 years. Belgium has followed the same strategy as the Netherlands, and the normal rules apply. The UK launched the Coronavirus Statutory Sick Pay Rebate Scheme, which targets employers with fewer than 250 employees. The rebates cover up to 2 weeks of SSP and are payable if an employee is unable to work for the following reasons: they have Covid-19 symptoms; they are self-isolating because a cohabitant has symptoms; they are self-isolating after being informed by the National Health Service (NHS) or public health bodies that they have come into contact with a person with Covid-19 or a shielded person, and they have a letter from the NHS or a GP instructing them to remain at home for a period of at least 12 weeks.

4.2. Strengths and limitations

One limitation of this study is its qualitative design, which does not allow us to generalise the results to other countries. A strength of this work is that it generates new hypotheses that can be tested in future studies. For instance, it would be interesting to study the distribution of the economic burden between employees, employers and social security systems, the taxing of the labour force and the consequences for employment and public health systems.

We cannot rule out the possibility that more knowledge could have been gained if we had collected and analysed information from other, or additional, countries. However, we believe that most of the inscriptions for the networks of actors were included for the countries studied.

4.3. Future research

The ANT perspective should be explored further in sick-leave research to develop better theoretical models for comparative analyses of sick-leave. Important contextual factors, such as labour force participation, temporary employment, unionisation and other social, historical and cultural perspectives, should also be considered in future research, especially in studies that compare sick-leave across countries.

Paid sick leave is viewed as a key component in combating health and social inequalities according to the ILO Conventions and the Decent Work Agenda [33]. A better understanding of risk- and burden-sharing between employees, employers and other tax payers in future research could contribute to improving the schemes.

5. Conclusion

This assessment of the differences in burden and responsibility sharing between the social protection system, employers and employees shows that countries with shorter employer sick-pay periods also have stricter employer follow-up responsibilities because, in practice, they become gatekeepers for the public sickness benefit scheme. In Germany and the UK, employers have few follow-up requirements compared with the Nordic countries because the former bear most of the sickness absence costs. This is also true in Iceland, where employers carry most of the costs and have no obligation to follow up on sick-listed employees. The situation in the Netherlands is paradoxical: employers have strict obligations in the follow-up regime, despite covering all the sick-leave costs.

Appropriate rehabilitation and retaining measures, as well as a comprehensive prevention agenda, should underpin sickness benefit policies. The results show that the incentives for preventing sickness absence from the workplace are weak in most of the countries studied. Further research is needed to identify the optimal burden sharing of the cost of sickness absence between employees, employers and tax-based social insurance programmes. Important contextual factors such as labour force participation, temporary employment, unionisation and other social, epidemiological, historical and cultural perspectives should be considered in future sick-leave research, especially in studies that compare sick-leave across countries.

The Covid-19 pandemic has revealed the importance of social protection systems, including income security, when health problems arise. During the pandemic, most countries adjusted their sick-pay system and increased coverage to reduce the risk of spreading Covid-19 by employees who would otherwise work while sick or when they should self-quarantine.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.healthpol.2022.05.002.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Anema J.R., Prinz C., Prins R. Handbook of work disability. Springer; 2013. Sickness and disability policy interventions; pp. 357–371. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anema J.R., Schellart A.J., Cassidy J., Loisel P., Veerman T., Van der Beek A. Can cross country differences in return-to-work after chronic occupational back pain be explained? An exploratory analysis on disability policies in a six country cohort study. J Occup Rehabil. 2009;19(4):419. doi: 10.1007/s10926-009-9202-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barmby T.A., Ercolani M.G., Treble J.G. Sickness absence: an international comparison. Econ J. 2002;112(480):F315–F331. doi: 10.1111/1468-0297.00046. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barnay T. Health, work and working conditions: a review of the European economic literature. Eur J Health Econ. 2016;17(6):693–709. doi: 10.1007/s10198-015-0715-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bliksvær, T., & Helliesen, A. (1997). Sickness absence: a comparative study of 11 countries in the Luxembourg employment study (LES): Norsk institutt for forskning om oppvekst, velferd og aldring.

- 6.Brandolini A., Viviano E. Behind and beyond the (head count) employment rate. J R Stat Soc: Ser A (Stati Soc) 2016;179(3):657–681. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brandolini A., Viviano E. Measuring employment and unemployment. IZA World Labor. 2018;(445) [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bryson A., Dale-Olsen H. Vol. 47. Emerald Publishing Limited; 2019. The role of employer-provided sick pay in Britain and Norway; pp. 227–252. (Health and labor markets). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carroll N., Richardson I., Whelan E. Service science: an actor-network theory approach. Int J Actor-Netw Theory Technol Innov (IJANTTI) 2012;4(3):51–69. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chaupain-Guillot S., Guillot O. Sickness benefit rules and work absence: an empirical study based on European data. Rev D'écon Politi. 2017;127(6):1109–1137. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chilcote, R. H. (2018). Theories of comparative politics: the search for a paradigm reconsidered: Routledge.

- 12.Clasen J. Income security during sickness absence. What do British middle-classes do? Soc Policy Administr. 2017;51(7):1101–1118. [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Rijk A. Arbeidsre-integratie blijft mensenwerk. Tijdschr Voor Gezondheidswetensch. 2018;96(5):208–215. [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Rijk A., van Raak A., van der Made J. A new theoretical model for cooperation in public health settings: the RDIC model. Qual Health Res. 2007;17(8):1103–1116. doi: 10.1177/1049732307308236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferragina E., Seeleib-Kaiser M. Welfare regime debate: past, present, future. Policy Politics. 2011;39(4):583–611. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frick B., Malo M.Á. Labor market institutions and individual absenteeism in the European Union: the relative importance of sickness benefit systems and employment protection legislation. Ind Relat: J Econ Soc. 2008;47(4):505–529. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Galis V. Enacting disability: how can science and technology studies inform disability studies? Disabil Soc. 2011;26(7):825–838. doi: 10.1080/09687599.2011.618737. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gimeno, Benavides F., Benach J., Amick B. Distribution of sickness absence in the European Union countries. Occup Environ Med. 2004;61(10):867–869. doi: 10.1136/oem.2003.010074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gimeno, Bültmann U., Benavides F.G., Alexanderson K., Abma F.I., Ubalde-López M., Delclos G.L. Cross-national comparisons of sickness absence systems and statistics: towards common indicators. Euro J Public Health. 2014;24(4):663–666. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cku070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heymann J., Rho H.J., Schmitt J., Earle A. Ensuring a healthy and productive workforce: comparing the generosity of paid sick day and sick leave policies in 22 countries. Int J Health Serv. 2010;40(1):1–22. doi: 10.2190/HS.40.1.a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koning P. IZA World of Labor; 2016. Privatizing sick pay: does it work? [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koning P., Lindeboom M. The rise and fall of disability insurance enrollment in the Netherlands. J Econ Perspect. 2015;29(2):151–172. doi: 10.1257/jep.29.2.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Landman, T. (2002). Issues and methods in comparative politics: an introduction: routledge.

- 24.Latour B. On actor-network theory: A few clarifications. Soziale welt. 1996:369–381. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Law J. Notes on the theory of the actor-network: Ordering, strategy, and heterogeneity. Syst Pract. 1992;5(4):379–393. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Law, J., & Hassard, J. (1999). Actor network theory and after.

- 27.Mair P. A new handbook of political science. 1996. Comparative politics: an overview; pp. 309–335. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nelson K., Fredriksson D., Korpi T., Korpi W., Palme J., Sjöberg O. The social policy indicators (SPIN) database. Int J Soc Welfare. 2020;29(3):285–289. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Osterkamp R., Röhn O. Being on sick leave: possible explanations for differences of sick-leave days across countries. Cesifo Econ Stud. 2007;53(1):97–114. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Palme M., Persson M. Sick pay insurance and sickness absence: some european cross-country observations and a review of previous research. J Econ Surv. 2020;34(1):85–108. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Prins R., De Graaf A. Comparison of sickness absence in Belgian, German, and Dutch firms. Occup Environ Med. 1986;43(8):529–536. doi: 10.1136/oem.43.8.529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Raub A., Chung P., Batra P., Earle A., Bose B., Jou J., Heymann J. Paid leave for personal illness: a detailed look at approaches across OECD countries. WORLD Policy Anal Center. 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Scheil-Adlung X., Sandner L. Evidence on paid sick leave: observations in times of crisis. Intereconomics. 2010;45(5):313–321. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schliwen A., Earle A., Hayes J., Heymann S.J. The administration and financing of paid sick leave. Int Labour Rev. 2011;150(1-2):43–62. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sjöberg O. Employee collective voice and short-term sickness absence in Europe. Eur J Ind Relat. 2017;23(2):151–168. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Söderström S. Socio-material practices in classrooms that lead to the social participation or social isolation of disabled pupils. Scand J Disabil Res. 2016;18(2):95–105. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Spasova, S., Bouget, D., & Vanhercke, B. (2016). Sick pay and sickness benefit schemes in the European Union: background report for the Social Protection Committee's In-Depth Review on sickness benefits.

- 38.Thomann E. Handbook of research methods and applications in comparative policy analysis. Edward Elgar Publishing; 2020. Qualitative comparative analysis for comparative policy analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Van der Wel K.A., Dahl E., Thielen K. Social inequalities in ‘sickness’: European welfare states and non-employment among the chronically ill. Soc Sci Med. 2011;73(11):1608–1617. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Van der Wel K.A., Dahl E., Thielen K. Social inequalities in “sickness”: does welfare state regime type make a difference? A multilevel analysis of men and women in 26 European countries. Int J Health Serv. 2012;42(2):235–255. doi: 10.2190/HS.42.2.f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van Raak A., de Rijk A., Morsa J. Applying new institutional theory: the case of collaboration to promote work resumption after sickness absence. Work, Employ Soc. 2005;19(1):141–151. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.