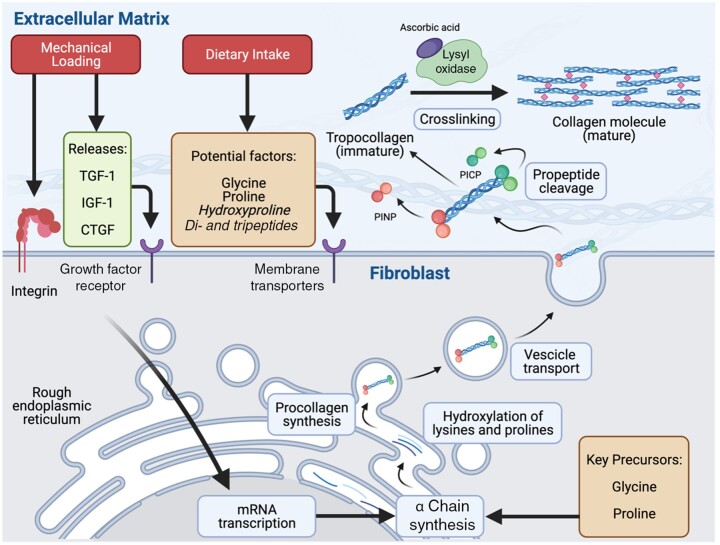

Figure 1.

Graphical representation of the key stages in collagen synthesis. Fibroblasts are embedded in a longitudinal orientation within the extracellular matrix (ECM) of various tissues (eg, skeletal muscle, tendon). Mechanical loading results in increased tension within the connective tissue, resulting in signal transduction through integrin activation and/or the release and binding of growth factors (eg, TGF-1, IGF-1, CTGF) on their respective membrane receptors. These signals are transduced to the nuclei of the fibroblast, resulting in increased mRNA transcription and α chain synthesis, which occurs in the rough endoplasmic reticulum. Part of the prolines and lysines in the α chains are hydroxylated into hydroxyproline and lysine, respectively, and 3 α chains are assembled into procollagen. Procollagen is packaged into vesicles and exported to the ECM. Extracellularly, procollagen peptidases cleave the propeptide regions (eg, procollagen type I N-terminal propeptide, and procollagen type I carboxy-terminal propeptide), allowing the resulting collagen monomers (tropocollagen) to stack spontaneously in an overlapping and parallel fashion. Lysyl oxidase activity, which requires ascorbic acid as a cofactor, forms cross-links between tropocollagen molecules, resulting in the formation of mature collagen within the extracellular network. Food ingestion, and collagen peptides in particular, has been proposed to deliver anabolic stimuli (eg, hydroxyproline, peptides) and key precursor amino acids (eg, glycine and proline) required to increase collagen synthesis. However, the proposed anabolic properties of food intake on muscle connective tissue synthesis rates in humans appear to have no stimulatory role (eg, leucine-rich protein) or have not yet been examined (eg, hydroxyproline, glycine, proline, peptides). CTGF, connective tissue growth factor; IGF-1, insulin-like growth factor-1; TGF-1, transforming growth factor-1