Abstract

In this study, we report about the preparation of nickel cobalt telluride nanorods (NiCoTe NRs) by the hydrothermal method using ascorbic acid and cetyltrimethylammonium bromide as reducing agents. The NiCoTe NRs (NCT 1 NRs) were characterized through use of different methods. The nonlinear optical measurements were carried out using Z-scan techniques. The results give the nonlinear absorption that arises from the combined two photon absorption and free carrier absorption. NCT 1 has an excellent electrocatalytic activity toward hydrogen peroxide with a sensitivity of 3464 μA mM–1 cm–2, a wide linear range of 0.002–1835 μM, and the lower detection limit of 0.02 μM, and the prepared electrode was strong in sensing in vivo H2O2 free from raw 264.7 cells. Therefore, the binary transition metal chalcogenide based nanostructures have promising potential in live cell biosensing applications.

1. Introduction

Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) plays a crucial role in biological systems, food, pharmaceutical industries, environmental protection, and clinical studies. H2O2 is a reactive oxygen species (ROS) which leads to various health issues, such as cancer, Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s diseases, and cardiovascular and neurodegenerative diseases.1−3 On the other hand, it has excellent antiseptic, oxidizing in industries, bleaching agent, and antibacterial properties. For the detection of H2O2 many analytical tools, such as fluorometric, chemiluminescent, spectrophotometric, volumetric, photometric, and electrochemical methods, were utilized. Electrochemical techniques are suitable for the amperometric determination of H2O2 because of the advantages of being cost-effective, repetitive, highly selective and sensitive, and user-friendly and having wide linear range, fast response, and lower detection limit.2−5 The electrochemical biosensor shows highly electrocatalytic activity toward the oxidation or reduction of H2O2 and achieves highly selective detection of H2O2 at the nanomolar level.5 Numerous pieces of evidence were found for an H2O2 sensor which is not sensible for identifying H2O2 in existing cells owing to the elevated intricacy of the existing structure and also is less focused on in vivo H2O2. It has extremely high selectivity, reproducibility, and stability. It is evident that the electrochemical exposure of H2O2 is found to be hard in active cells.1

Recently, many researchers have focused on metal chalcogenide H2O2 biosensors because of their electrical conductivity, electrochemical activity, enlarged electrocatalytic sites due to the mixed valence state, and enriched redox properties. A few reports on metal chalcogenides are based on electrochemical detection of H2O2 in living cells, such as MoS2, PtW/MoS2, MoS2/CN, and NiCo2S4@CoS2. Wang et al. have fabricated MoS2 with a high sensitivity of 152 mA cm–2 M–1, RSD of 1.9% of its current response to 6.00 mM glucose, and good stability.5 Dynamic H2O2 released from mouse breast cancer cell line 4T1 monitored over a PtW/MoS2 nanocomposite electrode has been reported by Zhu et al.6 Dai et al. synthesized MoS2/CN nanowires having good catalytic performance toward H2O2 with the limit of detection 0.73 μM and the wide linear range of 2 to 500 μM.7 The NiCo2S4@CoS2 electrode displayed the sensitivity of 1.49 μA μM–1 cm–2, lower detection limit of 2 nM, and linear range of 12.64 nM to 2104 μM.1 The CoNiSe/rGO nanocomposite shows a good electrocatalytic activity against glucose with the sensitivity of 18.89 mA mM–1 cm–2, LOD of 0.65 μM, and linear range of 1 to 4000 μM.8

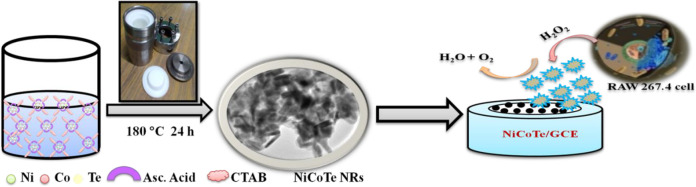

Semiconductor nanostructures of transition metal chalcogenides also exhibited interesting nonlinear optical properties and applications such as nonlinear absorption, nonlinear refraction and optical limiting, optical switching, pulse-shaping devices, optical communication, optical signal processing, optical storage, and mode-lockers to the extraordinary intrinsic properties benefiting from the strong confinement of excitons.9−12 There are some reports of transition metal chalcogenides: for example, Manikandan et al. have discussed that the nonlinear absorption coefficient and optical limiting for CdTe nanorods (NRs) is 12.0 × 10–10 m/W and the optical limiting is 1.60 J/cm2 for 100 μJ;13 the nano- and femtosecond excitation nonlinear absorption coefficients for PbTe nanorods are on the order of 10–22 and 10–29 m3 W–2;14 broadband optical limiters at the excitation wavelengths 532 and 1064 nm have been studied for Te and Ag2Te nanowires;15 Yuan et al. have reported that the third order susceptibility of the Cu2Se/RGO composite increased 5-fold compared to graphene;10 nonlinear absorption and refractive coefficients were calculated for ZrSe3 nanoflakes under 532 nm;12 Au coated CdS nanoparticles show the absorption coefficient and refractive index 6.28 × 10–6 cm/W and 4.86 × 10–11 cm/W;11 ZnS nanoparticles display a two photon absorption and self-defocusing process while doping with magnetic materials such as Fe, Co, and Ni is reduced.16 In this work, for the first time, NiCoTe NRs were used as an electrode material for nonenzymatic hydrogen peroxide biosensing of endogenous H2O2 and an optical limiter. Our study reveals that the NiCoTe nanorods hold excellent electrocatalytic sensing properties to H2O2 in lab samples and also in real samples. A real time tracking and quantification of H2O2 release in living cells is demonstrated using NiCoTe NRs. Another advantage of this electrochemical system is it is demonstrated to be flexible and stretchable; therefore, it can be a desirable electrode for on-body sensors such as wearable and in vivo sensors. Scheme 1 illustrates the hydrothermally synthesized NiCoTe NRs for the real time quantification of endogenous H2O2 released from the RAW 246.7 cell.

Scheme 1. Illustration of the Preparation of NiCoTe NRs for H2O2 Produced by RAW 267.4 Cells.

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Preparation of Nickel Cobalt Telluride Nanorods

Starting materials such as ascorbic acid (C6H8O6), cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB), sodium telluride (Na2TeO3), nickel acetate (Ni(CH3CO2)2·2H2O), cobalt acetate (Co(CH3COO)2·4H2O) from (Sigma-Aldrich), and deionized water from a milli-Q-ultra pure (18.2 MΩ cm–1) system were used. Initially, CTAB was dissolved in 40 mL of deionized water with vigorous stirring to form a homogeneous solution. Then C6H8O6, 1.88 mmol of Na2TeO3, 1.25 mmol of Ni(CH3CO2)2·2H2O, and 0.63 mmol of Co(CH3COO)2·4H2O salts were added to the above solution. Immediately, white TeO2 precipitate was observed. This solution mixture was stirred for nearly 30 min with the addition of 40 mL of deionized water. The solution was transferred to a Teflon-lined stainless-steel autoclave and maintained at 180 °C for 24 h. The final product was washed well with ethanol and distilled water several times to remove the excess impurities. Then it was dried to obtain the sample coded as NCT 1. Moreover, the samples coded as NCT 2 and NCT 3 were obtained by the same process with 0.94 and 0.63 mmol of Ni(CH3Co2)2·2H2O and 0.94 and 1.25 mmol of Co(CH3COO)2·4H2O, respectively. Wet chemically prepared nickel cobalt telluride (NCT-W) is briefly discussed in the Supporting Information.

2.2. Characterization

Nonlinear optical properties were studied using a Nd:YAG laser (532 nm, 9 ns, 10 Hz) by the Z-Scan technique. NiCoTe nanorod powder was sonicated for 1 h before the laser excitation, and it was taken into the 1 mm quartz cuvette. The electrochemical investigations were made using a CHI 1205A workstation, Amperometric measurements were performed using an analytical rotator AFMSRX (PINE instruments) with a rotating disc electrode (RDE, area = 0.24 cm2), and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) studies were carried out using an EIM6ex Zahner instrument for biosensing applications.

2.3. Electrochemical Measurements

2.3.1. Sensor Studies

The electrochemical experimentation was performed through a predictable three electrode cell such as NiCoTe/GCE as a functioning electrode (area 0.071 cm2), inundated Ag/AgCl (saturated KCl) as an orientation electrode, Pt wire as a counterion electrode, and 0.1 M phosphate buffer (PB) as a sustaining electrolyte. The customized electrodes were equipped on the glassy carbon electrode (GCE) plane through a simple drop emitting stratagem. Initially the GCE surface was precleaned through cycling amid 0.0 and 0.8 V, in 0.1 M PB (pH 7) used for 10 cycles at a scan velocity of 50 mV/s. Seven microliters of NCT 1 was plunged on the precleaned GCE and dehydrated at ambient warmth. Preceding every electrochemical trial the electrolyte results were deoxygenated along with prepurified nitrogen gas for 15 min.

2.3.2. Cell Culture to Cultivate Mammalian Cells

Unprocessed 264.7 cells (murine macrophages) were matured in 5% CO2 in a 12.5 cm2 urn with Dulbecco’s tailored Eagle’s medium (DMEM) along with 1% antibiotics (100 U/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (GIBCO, LOT198 9515, NY, USA)) and 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS) at 37 °C. The 90% matured combined cells flow together, and the processed cells were frayed and composed in the course of centrifugation for 15 min at 1500 rpm. Subsequently the cells were rinsed with 0.01 M phosphate buffer saline for numerous periods. The number of cells was calculated via a hemocytometer. To kindle the fabrication of H2O2 from unrefined 264.7 cells, lipopolysaccharide (LPS, 97%), a prominent stimulant of H2O2, was inserted into the cell solution.

3. Results and Discussion

Structural and morphological studies, such as XRD, XPS, BET, and TEM, for the prepared samples have been analyzed and discussed in our previous report.17Figure S1(a,b) displays the FESEM images of NCT 1 and NCT W. The prepared materials show uniform morphology of nanorods. Figure S1c reveals the the XRD pattern for NCT-W corresponds to nickel telluride [International Centre for Diffraction Data (ICDD) number 00-065-3665] and cobalt telluride (ICDD number 00-089-7180). The diffraction peaks at 26.91, 27.68, 32.13, 40.57, 41.49, 43.49, 51.23, 63.05, 65.94, 67.85, and 75.73° are assigned for nickel telluride. The peaks at 27.68, 32.13, 35.00, 35.98, 37.93, 40.57, 46.40, 49.71, 56.81, and 71.62° are assigned for cobalt telluride.

3.1. Optical Limiter

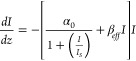

The change in absorption of a material induced by an intense laser beam is measured by the open aperture (OA) Z-scan technique at 532 nm under nanosecond laser excitation to obtain the nonlinear absorption coefficients. The OA Z-scan traces of NCT composites at 150 μJ (Figure 1a) demonstrate the presence of a valley-like pattern (decreased transmission) near the focal point indicating reverse saturable absorption (RSA). The experimental data strongly rely on the 2PA equation with a weak saturable absorption, and the observed nonlinearity due to the electronic transition can be considered as an effective 2PA.

| 1 |

where αo,I, Is, and βeff are the linear absorption coefficient at 532 nm, input laser intensity, saturation intensity, and two photon absorption coefficient, respectively. The corresponding propagation equation is given as

|

2 |

The two absorption coefficient (βeff) gets enhanced for the NCT 2 (11 × 10–10 mW–1) compared with NCT 1 (4.8 × 10–10 mW–1) and NCT 3 (4.1 × 10–10 mW–1). Genuine 2PA in metal tellurides is rarely observed; however, FCA is associated with the nonlinearity. Also, the experiment at 9 ns laser pulses with the repetition rate 0.11 s allows for multiple absorptions, which greatly enhances nonlinear absorption by the combined effect of 2PA with the free carrier absorption (FCA) process. A material with the lowest optical limiting threshold (OLT) is the desirable factor for a good optical limiter18 and is evaluated from the normalized transmittance against the input influence. The OLT curves for the nanocomposite are illustrated in Figure 1b and resemble the behavior of β. NCT 2 possesses a low OLT of 1.80 J cm–2, indicating a potential optical limiter.

Figure 1.

NCT 1, NCT 2, and NCT 3 at 150 energy of nanosecond laser excitation: (a) open aperture Z-scan; (b) optical limiting curves.

The calculated β and OLT values are summarized and compared with the other metal chalcogenides in Table 1. The values are higher for the carbon coated samples compared to the pure chalcogenide, which is due to the synergetic effect of the composites.19 Vineeshkumar et al. reported that the nonlinear absorption increased with the input energy, which reveals the effective 2PA cross section for ZnFeS.18 rGO-PbS shows better optical limiting behavior due to the two photon induced FCA phenomenon.20 In the present work, it is found that the higher β for NCT 2 compared to the other metal chalcogenides is due to the combination of effective 2PA and FCA.

Table 1. Comparison Table for the Third Order Nonlinear Optical Parameters of the Metal Tellurides with Some Other Metal Chalcogenides.

3.4. Hydrogen Peroxide Sensing

The cyclic voltammograms (CVs) of bare GCE and NCT 1/GCE electrodes measured at the scan rate of 5 mV/s in the potential window of 0 to −0.8 V using 0.05 M PBS are shown in Figure 2a. The NCT 1 modified electrode displays a cathodic peak current at −0.52 V that reveals the significant electrocatalytic activity upon H2O2 reduction. Figure 2b reveals the CV response of NCT 1/GCE in PBS containing 1 mM H2O2 at a scan rate from 10 to 100 mV/s. The cathodic peak current increases with the lower to higher scan rate. The plot between the cathodic peak current and the square root of the scan rate exhibits good linearity with the correlation coefficient (r2) 0.9815 indicating a diffusion-controlled reduction process (Figure 2c). Figure 2d represents the CV of the NCT 1/GCE electrode for concentrations of H2O2 ranging from 20 to 160 μM. The cathodic peak current increases linearly as the concentration of H2O2 increases. Figure 2e illustrates chronoamperometry (CA) of the NCT 1/GCE electrode after the injection of concentrations of H2O2 at regular intervals into the stirred PBS at the applied potential of −0.52 V. The steady state current has been reached in 5 s, indicating a fast response behavior with the linear increase of H2O2 concentration for the range of 0.02 to 1835 μM. A plot between H2O2 concentration and current exhibits a good linearity with the sensitivity of 3464.7 μA mM–1 cm2 and the LOD of 0.02 μM (inset of Figure 2e). The selectivity of the electrode in H2O2 detection has been tested in the presence of common interfering agents such as 0.5 mM dopamine (DA), uric acid (UA), ascorbic acid (AA), and folic acid (FA) in PBS at a −0.52 V potential (Figure 2f). The electrode quickly responds to H2O2, but it is not sensitive to other species. The NCT 1/GCE electrode displays an excellent selectivity toward H2O2. Hydrothermally prepared NiCoTe shows higher sensitivity, linear range, and limit of detection than wet chemically prepared NiCoTe. The sensitivity, linear range, and limit of detection for the prepared materials and some other metal chalcogenides are listed in Table 2.

Figure 2.

(a) CVs for bare GCE and NCT 1/GCE. (b) CVs for NCT 1/GCE containing 50 μM H2O2 at different scan rates. (c) Plot for cathodic and anodic peak current against log (υ). (d) CVs for NCT 1/GCE with concentrations of H2O2. (e) Chronoamperometric analysis for concentrations of H2O2 (inset: linear relation between current and H2O2 concentration). (f) Addition of H2O2, DA, UA, AA, and FA.

Table 2. Comparison of the Different Modified Electrodes for Electrochemical Sensing of H2O2.

| Sample | Sensitivity (μA mM–1 cm2) | Limit of detection (μM) | Linear range (μM) | ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Te | 757 | 28.4 | 0.67–8.04 | (2) |

| CdTe | 1326 | 0.1 | 0.67–8.04 | (13) |

| CoS/RGO | 2.519 μM | 0.042 | 0.1–2542.2 | (3) |

| PtW/MoS2 | 1.71 μM | 0.005 | 1–200 | (6) |

| NiCo2S4@CoS2 | 1.49 μM | 0.002 | 0.1264–2104 | (1) |

| NiS | 82.73 | 5.2 | 10–870 | (22) |

| NCT W | 93.428 | 0.01 | 5–25 | Present work |

| 6.93 | 0.17 | 30–100 | ||

| NCT 1 | 3464.7 | 0.02 | 0.02–1835 |

The electrochemical characteristics of NiCoTe-W NRs were analyzed through CVs using Nafion as a binder in deoxygenate PBS. Figure S2a gives the voltammograms recorded on bare GCE and NCT-W/GCE at a sweep rate of 40 mV/s between 0 and −1.0 V. Figure S2b reveals the CV response of NCT W/GCE PBS at scan rate from 10 to 100 mV/s. Figure S2c show the current response of a NCT-W/GCE modified electrode with different concentrations of H2O2 ranging from 45 to 180 μM. With the addition of H2O2 the peak current increases from 0.514 to 0.528 mA. Figure S2d displays the CA response of the NCT-W/GCE modified electrode where it shows a quick response to the concentration of H2O2. While maintaining PBS in a stirring condition, different concentrations of H2O2 are added at regular intervals. The CA analysis was studied on the chemically modified electrode by applying a constant potential of −0.4 V.

The calibration curve for the sensor was obtained by plotting the current I, measured for each hydrogen peroxide addition, against concentration. Two main behaviors can be identified (Figure S2e); the first at low H2O2 levels (5–25 μM) was relevant to a linear variation of I toward concentration with a considerable slope (93.428 μA μM–1 cm2) with the detection limit of 0.01 μM; the second was observed at higher H2O2 concentrations (30–100 μM) with a slight decrease in sensitivity (6.93 μA μM–1 cm2) with the detection limit of 0.17 μM being obtained with a response time of 5 s. The anti-interference ability has been tested using the most common interfering species, including AA, H2O2, oxalic acid (Ox.A), DA, glucose (GC), UA, and fructose (FT) (Figure S2f). The current response does not change after addition of the same concentration of AA, Ox.A, DA, GC, UA, and FT. These results indicate that the modified NCT-W/GCE electrode performs a good selectivity toward H2O2, and it has the ability to reduce the interference from the electroactive species.

To evaluate the stability of the NiCoTe/GCE modified electrode, it was monitored every day while the electrode was kept in PBS (pH 0.7) over the time interval of 3 weeks. The electrode retained 92% of its initial current even after 3 weeks of continuous usage, revealing good durability. For ensuring reproducibility, tests were performed with five different NiCOTe/GCE electrodes in the presence of H2O2, which exhibited the relative standard deviation (RSD) of 3.48%. The sensor has suitable storage stability toward H2O2 sensor applications.

With the aid of cell culture equipment, RAW 264.7 cells were matured and then shifted into an electrochemical cell which consists of 2 × 106 cells balanced in 20 mL of broth medium (pH 7.0). Subsequently the amperometric testing (electrode potential = −0.52 V vs Ag/AgCl) in hydrodynamic conditions (electrode rotation speed 1500 rpm) was performed. Figure 3a shows an increase in the sturdy conditions of the current attained. A rapid rise in amperometric current after the insertion of 11.5 nM LPS into the electrolyte was achieved in less than 5 s. The LPS supply to the cells provokes them to construct H2O2. NCT 1/GCE perceives the as-produced H2O2 and proves the information as an amperometric signal. The results testify that the developed biosensor is to be used to detect H2O2. With the RAW 267.4 cell, the current has been increased significantly according to the amount of H2O2 in the laboratory sample and serum sample. Figure 3b displays the amperometric response of the NCT 1/GCE electrode in a supporting electrolyte injected with laboratory sample (1 μM H2O2) and serum sample (1 μM H2O2), and the maximum current has been reached in a few seconds. The continuous injections of H2O2 result in further increase of the current, which is proportional to the concentration of H2O2. These results demonstrate that the NCT 1/GCE electrode can be used for the detection of H2O2 and could be useful for physiological and pathological studies.1,5,23Scheme 2 describes H2O2 release from RAW 267.4 living cells detected by the developed electrochemical sensor. This illuminates that the NCT 1/GCE NRs provide a promising platform to monitor H2O2.

Figure 3.

Real sample analysis amperometric response of the NCT 1/GCE electrode in a supporting electrolyte containing (a) RAW 264.7 cells with injection of LPS stimulant or (b) human serum sample injected with laboratory sample ((a) 1 μM H2O2 and (b) 1 μM H2O2 spiked).

Scheme 2. Illustration for the Electrochemical Sensing Applications of the NCT 1/GCE Modified Electrode.

4. Conclusion

NiCoTe was successfully synthesized through the hydrothermal method. The optical limiting and nonlinear absorption coefficients were calculated by Z-scan measurement at the nanosecond pulse of the Nd:YAG laser. NCT 2 gives the optical limiting threshold and nonlinear absorption coefficient of 1.80 J/cm2 and 11 m/W × 10–10. A good sensitivity (3464 μA mM–1 cm–2) and response time (5 s) at the detection limit 0.02 μM revealed that the electrode can be used for the detection of cellular level H2O2. NCT 1 effectively identified and quantified H2O2 release in real time from RAW 264.7 cells. Furthermore, this work demonstrates that the synthesized material offers a new possibility to achieve the best optical limiter.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Department of Science and Technology, New Delhi, for providing the Nd:YAG laser under FIST.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.1c06007.

Detailed Experimental Section and electrochemical measurements for biosensor studies, FE-SEM images of NCT-1 NRs and NCT-W, XRD image of NCT-W (Figure S1), and cyclic voltammetry and chronoamperometric analysis of NCT-W (Figure S2) (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Mani V.; Shanthi S.; Peng T.-K.; Lin H.-Y.; Ikeda H.; Hayakawa Y.; Ponnusamy S.; Muthamizhchelvan C.; Huang S.-T. Real-time quantification of hydrogen peroxide production in living cells using NiCo2S4@CoS2 heterostructure. Sensors Actuators B Chem. 2019, 287, 124–130. 10.1016/j.snb.2019.02.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Waldiya M.; Bhagat D.; R N.; Singh S.; Kumar A.; Ray A.; Mukhopadhyay I. Development of highly sensitive H2O2 redox sensor from electrodeposited tellurium nanoparticles using ionic liquid. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2019, 132, 319–325. 10.1016/j.bios.2019.02.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubendhiran S.; Thirumalraj B.; Chen S. M.; Karuppiah C. Electrochemical co-preparation of cobalt sulfide/reduced graphene oxide composite for electrocatalytic activity and determination of H2O2 in biological samples. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2018, 509, 153–162. 10.1016/j.jcis.2017.08.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manikandan M.; Dhanuskodi S.; Maheswari N.; Muralidharan G.; Revathi C.; Rajendra Kumar R. T.; Mohan Rao G. High performance supercapacitor and non-enzymatic hydrogen peroxide sensor based on tellurium nanoparticles. Sens. Bio-Sensing Res. 2017, 13, 40–48. 10.1016/j.sbsr.2017.02.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T.; Zhu H.; Zhuo J.; Zhu Z.; Papakonstantinou P.; Lubarsky G.; Lin J.; Li M. Biosensor Based on Ultrasmall MoS2 Nanoparticles for Electrochemical Detection of H2O2 Released by Cells at the Nanomolar Level. Anal. Chem. 2013, 85 (21), 10289–10295. 10.1021/ac402114c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu L.; Zhang Y.; Xu P.; Wen W.; Li X.; Xu J. PtW/MoS2 hybrid nanocomposite for electrochemical sensing of H2O2 released from living cells. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2016, 80, 601–606. 10.1016/j.bios.2016.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai H.; Chen D.; Cao P.; Li Y.; Wang N.; Sun S.; Chen T.; Ma H.; Lin M. Molybdenum sulfide/nitrogen-doped carbon nanowire-based electrochemical sensor for hydrogen peroxide in living cells. Sensors Actuators B Chem. 2018, 276, 65–71. 10.1016/j.snb.2018.08.081. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Amin B. G.; Masud J.; Nath M. A non-enzymatic glucose sensor based on a CoNi2Se4/rGO nanocomposite with ultrahigh sensitivity at low working potential. J. Mater. Chem. B 2019, 7 (14), 2338–2348. 10.1039/C9TB00104B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L. Q.; Zhang Y. B.; Yan T. F.; Li Y.; Jia G. Z.; Xu H. Z.; Zhang X. H. Third-Order Nonlinear Optical Response near the Plasmon Resonance Band of Cu2-xSe Nanocrystals. Chin. Phys. Lett. 2017, 34 (1), 014205. 10.1088/0256-307X/34/1/014205. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Y.; Zhu B.; Cao F.; Wu J.; Hao Y.; Gu Y. Enhanced nonlinear optical properties of the Cu2Se/RGO composites. Results Phys. 2021, 27, 104568. 10.1016/j.rinp.2021.104568. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mathew S.; Samuel B.; Mujeeb A.; Kailasnath M.; Nampoori V. P. N.; Girijavallabhan C. P. Effect of Au coating on optical properties of CdS nanoparticles and their optical limiting studies. Opt. Mater. 2017, 72, 673–679. 10.1016/j.optmat.2017.07.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J.; Tao Y.; Fan L.; Wu Z.; Wu X. Visible light nonlinear absorption and optical limiting of ultrathin ZrSe3 nanoflakes. Nanotechnology 2016, 27, 465203. 10.1088/0957-4484/27/46/465203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manikandan M.; Revathi C.; Senthilkumar P.; Amreetha S.; Dhanuskodi S.; Rajendra Kumar R. T. CdTe nanorods for nonenzymatic hydrogen peroxide biosensor and optical limiting applications. Ionics 2020, 26 (4), 2003–2010. 10.1007/s11581-019-03361-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sridharan K.; Tamilselvan V.; Yuvaraj D.; Narasimha Rao K.; Philip R. Synthesis and nonlinear optical properties of Lead Telluride nanorods. Opt. Mater. 2012, 34 (4), 639–645. 10.1016/j.optmat.2011.09.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Suchand Sandeep C. S.; Samal A. K.; Pradeep T.; Philip R. Optical limiting properties of Te and Ag2Te nanowires. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2010, 485, 326–330. 10.1016/j.cplett.2009.12.065. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dehghani Z.; Shadrokh Z.; Nadafan M. Optik The effect of magnetic metal doping on the structural and the third-order nonlinear optical properties of ZnS nanoparticles. Opt. - Int. J. Light Electron Opt. 2017, 131, 925–931. 10.1016/j.ijleo.2016.12.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Manikandan M.; Subramani K.; Dhanuskodi S.; Sathish M. One-Pot Hydrothermal Synthesis of Nickel Cobalt Telluride Nanorods for Hybrid Energy Storage Systems. Energy Fuels 2021, 35 (15), 12527–12537. 10.1021/acs.energyfuels.1c00351. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vineeshkumar T. V.; Raj D. R.; Prasanth S.; Unnikrishnan N. V.; Mahadevan Pillai V. P.; Sudarasanakumar C. Fe induced optical limiting properties of Zn1-xFexS nanospheres. Opt. Laser Technol. 2018, 99, 220–229. 10.1016/j.optlastec.2017.09.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xi G.; Wang C.; Wang X.; Qian Y.; Xiao H. Te/Carbon and Se/Carbon Nanocables: Size-Controlled in Situ Hydrothermal Synthesis and Applications in Preparing Metal M/Carbon Nanocables (M = Tellurides and Selenides). J. Phys. Chem. C 2008, 112 (4), 965–971. 10.1021/jp0764539. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao M.; Peng R.; Zheng Q.; Wang Q.; Chang M.-J.; Liu Y.; Song Y.-L.; Zhang H.-L. Broadband optical limiting response of a graphene–PbS nanohybrid. Nanoscale 2015, 7 (20), 9268–9274. 10.1039/C5NR01088H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ann Mary K. A.; Unnikrishnan N. V.; Philip R. Defects related emission and nanosecond optical power limiting in CuS quantum dots. Phys. E Low-Dimensional Syst. Nanostructures 2015, 74, 151–155. 10.1016/j.physe.2015.06.031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jana S.; Mondal G.; Mitra B. C.; Bera P.; Chakraborty B.; Mondal A.; Ghosh A. Facile synthesis of nickel oxide thin films from PVP encapsulated nickel sulfide thin films: An efficient material for electrochemical sensing of glucose, hydrogen peroxide and photodegradation of dye. New J. Chem. 2017, 41 (24), 14985–14994. 10.1039/C7NJ02985C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y.; Wu C.; Zhou X.; Wu X.; Yang Y.; Wu H.; Guo S.; Zhang J. Graphene quantum dots/gold electrode and its application in living cell H2O2 detection. Nanoscale 2013, 5 (5), 1816. 10.1039/c3nr33954h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.