Abstract

Ruptured sinus of Valsalva aneurysm (RSOV) is an uncommon cause of high output heart failure. RSOV most commonly opens into the right ventricle followed by the right atrium and non-coronary cusp involvement is relatively uncommon. Infective endocarditis (IE) is a rare cause of RSOV. We report an interesting clinical scenario of IE causing RSOV managed by device closure. A 16-year-old male patient presented to the emergency department with acute chest pain, fever, and engorged neck veins. On cardiorespiratory system examination he had features of left ventricular failure. Blood culture revealed growth of Staphylococcus aureus. Echocardiography and computed tomography aortography confirmed the diagnosis of 9 mm type IV RSOV (non-coronary cusp to right atrium) with vegetation (5 × 6 mm). The patient refused surgery. When there was no apparent visible vegetation after 6 weeks of antibiotic therapy, we proceeded with 12-mm Amplatzer duct occluder II closure of the anatomical defect. Monthly follow up has been uneventful for 6 months. As per our knowledge this is the first ever reported case of documented definitive IE by S. aureus causing Sakakibara and Konno ruptured Type IV RSOV that has been managed successfully by device closure.

<Learning objective: Ruptured sinus of Valsalva aneurysm (RSOV) secondary to native valve infective endocarditis (IE) can occur in apparently healthy young individuals with no predisposing factor. Device closure is a good therapeutic option in selective cases of RSOV secondary to native valve IE. Further research is needed to understand the role of device closure in such clinical settings as an alternative to surgical options.>

Keywords: Acute heart failure, Aortic valve, Case report, Endocarditis

Introduction

Ruptured sinus of Valsalva aneurysm (RSOV) is a rare but potential cause of high output heart failure. Most RSOVs drain into the right ventricle and draining into the right atrium is relatively uncommon [1]. Moreover, infective endocarditis (IE) causing RSOV aneurysm is rare [2]. Unless RSOV is associated with any ventricular septal defect or aortic regurgitation it is amenable to device closure [3]. We report a rare clinical scenario of Staphylococcus aureus IE causing RSOV (from non-coronary cusp to right atrium) that we successfully managed with initial intravenous antibiotics followed by device closure of the anatomical defect. The report received ethical approval from Institutional Review Board and was performed with full informed written consent from the subject.

Case report

A 16-year-old non-diabetic, normotensive young male presented to the emergency room with acute onset chest pain followed by persisting dyspnea, orthopnea, and palpitation even at rest for 5 days. He was suffering from fever with chills and rigor and polyarthralgia but without any skin rash for 2 weeks. His past medical history was uneventful. On general survey he was febrile and had engorged pulsatile neck veins with distinct CV wave, no lymphadenopathy and normal fundoscopy. His pulse rate was 110/min and of high volume; blood pressure 130/50 mmHg in both arms; respiratory rate 24/min, regular. On cardiorespiratory examination he had hyperdynamic left ventricular (LV) apex with lower left para-sternal impulse and continuous thrill appreciable in bilateral lower parasternal areas. First and second heart sounds (S1 and S2, respectively) were normal with presence of LV third heart sound (S3) and continuous murmur with systolic prominence (not peaking around S2) best heard in bilateral lower parasternal area. There were bilateral basal rales. There was mild hepatomegaly whereas neurological system examination was non-contributory. Hence, he was suffering from acute LV failure due to a newly developed shunt from left heart to right heart with a strong possibility of RSOV because of age and mode of presentation.

Investigation profile

12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) (Online Fig. 1) showed sinus tachycardia and chest skiagram postero-anterior view (Online Fig. 2) showed pulmonary edema, with increased cardio-thoracic ratio. Serum troponin levels were not raised. Hemoglobin was 10 g/dL, total leucocyte count was high (22,300/mL) and neutrophil predominant. There was mild elevation of hepatic transaminases. Serum creatinine was 1.4 mg/dL. Covid 19 reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction was negative and he was also seronegative for human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B and C virus. Urine routine microscopic and culture examinations were within normal limits. All three blood culture sets came positive for growth of S. aureus sensitive to vancomycin. Echocardiography (2D and 3D) with Doppler study (Fig. 1 and Video 1) confirmed the diagnosis of 9 mm RSOV (non-coronary cusp to right atrium) with vegetation (5 × 6 mm), LV ejection fraction 75%, pulmonary artery peak systolic pressure 68 mmHg without any ventricular septal defect or aortic regurgitation and aortic valve was trileaflet. The final diagnosis was RSOV type IV (Sakakibara and Konno Classification) due to IE presenting with high output heart failure [4].

Fig. 1.

Echocardiography for assessment of RSOV and vegetation. (A) 2-D PSAX view showing the 9 mm RSOV aneurysm between NCS and RA. (B) 2-D color Doppler image of PSAX view showing flow through RSOV from NCS to RA. (C) 2-D PSAX view showing the 5 × 6 mm vegetation arising from NCC. (D) 3-D PSAX view showing the RSOV between NCS and RA and vegetation from NCC.

2-D, 2-dimensional; 3-D, 3- dimensional; NCC, non-coronary cusp; NCS, non-coronary sinus; PSAX, parasternal short axis; RA, right atrium; RSOV, ruptured sinus of Valsalva.

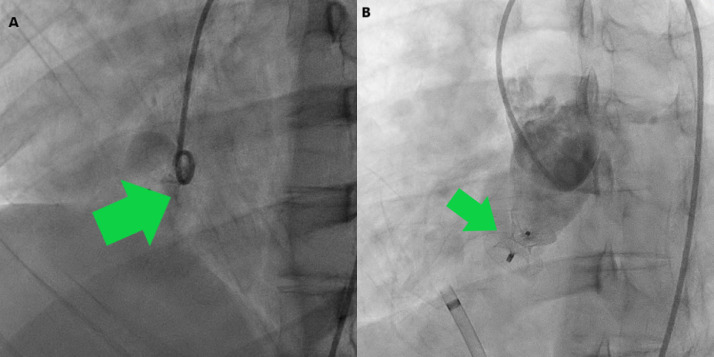

Fig. 2.

Cardiac catheterization. (A) Aortic root angiogram showing passage of dye from non-coronary sinus to right atrium. (B) 12 mm Amplatzer duct occluder II device occluding the ruptured sinus of Valsalva with no dye leakage.

Management

A heart team approach was taken and despite repeated and detailed counselling by a board consisting of 2 consultant cardiologists, 2 consultant cardiac surgeons, and 2 consultant microbiologists regarding the utmost importance of urgent surgical approach the patient and his relatives refused to undergo surgical intervention [5]. Thus, with the consensus of all the board members an alternative treatment plan was chalked out and the patient was put on intravenous ceftriaxone 2 g OD and gentamicin 3 mg/kg/day OD. After obtaining the blood culture report we started intravenous vancomycin 2 g/day in twice divided doses over 6 weeks. The patient became afebrile within 10 days. Throughout the duration he received furosemide, metoprolol succinate, and ramipril. Regular clinical examinations were undertaken to rule out any embolic manifestations. We weekly followed up the vegetation size by transthoracic echocardiography. When there was no apparent visible vegetation after 6 weeks of antibiotic therapy and blood cultures were negative, we proceeded with computed tomography (CT) of the aorta (Online Fig. 3) to clearly delineate the anatomy, which revealed 9.1 mm RSOV with normal coronary arteries and absence of residual vegetation. After final discussion and consensus in the heart team, device closure of the anatomical defect by the antegrade approach was performed (Fig. 2 and Video 2). A 12-mm size Amplatzer Duct Occluder (ADO) II was used (Fig. 3) after the size was confirmed from echocardiography, CT, and catheterization images and videos. The procedure was uneventful and done under fluoroscopy as well as transthoracic echocardiography with Doppler imaging guidance. During the procedure we were vigilant enough to include the entire windsock but not to impinge the aortic leaflets. Echocardiography after 24 hours of the procedure confirmed the well-placed device (Fig. 3). The patient became symptom-free in the immediate post-operative period and was discharged with tablet aspirin 75 mg for 6 months. Following the current European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines on IE, the patient was advised regarding endocarditis prophylaxis for the first 6 months (until expected endothelialization of the device) after the procedure with 2 g oral or intravenous amoxicillin if he underwent at-risk procedures such as dental procedures requiring intervention of the gingival or periapical region of teeth or perforation of the oral mucosa. Clinical and echocardiographic follow up has been uneventful for 6 months.

Fig. 3.

Post-operative echocardiography- 2D parasternal short-axis view showing the Amplatzer duct occluder II in-situ.

Discussion

Sinus of Valsalva aneurysm (SVA) is a rare structural heart disease that can occur isolated or may co-exist with ventricular septal defect, aortic regurgitation, or bicuspid aortic valve [6]. It may rupture into the cardiac chambers insidiously or acutely causing acute heart failure symptoms. SVA ruptures most commonly into the right ventricle (60%) or at the right atrium (29%), followed by the left atrium (6%) and left ventricle (4%), or at the pericardium (1%) [1]. Incidence of RSOV is five times higher in Asian countries with male: female ratio as 4:1 [7]. Right coronary cusp is the most commonly involved whereas non-coronary cusp involvement is relatively uncommon [4]. The unruptured aneurysm may be incidentally detected or may present with outflow tract obstruction or coronary insufficiency or tricuspid regurgitation or cardiac conduction abnormality. SVA occurs because of mal-fusion between the aortic media and annulus fibrosus of aortic valve. Affected sinus wall is often relatively elastin deficient. Transthoracic echocardiogram has 75% diagnostic accuracy for detection of ruptured or unruptured SVA [8]. IE, although rare, may cause rupture of SVA [2,9]. Our reported patient was a definitive case of IE as per Duke's modified criteria as two major criteria were fulfilled [10]. S. aureus is a virulent organism that often causes a fulminant course in IE [9]. Considering the RSOV as a fistula, which is by definition a communication between two neighboring cavities through a perforation, the presence of vegetation on the aneurysm, the clinical presentation of pulmonary edema and signs of high output heart failure, this was a case of IE to consider for an emergent/urgent surgery following the ESC guidelines [5]. Device therapy is not recommended by guidelines in cases of IE due to the risk of implanted device getting infected which can complicate the scenario and risk the patient's life, hence device closure was not the first choice in this case. Moreover, delay in urgent surgery can be fatal. The patient and his relatives’ refusal to undergo surgery despite repeated and detailed counselling made the heart team take this alternative approach. Extreme care was taken for the patient's wellbeing and for complete clearance of evidence of IE with 6 weeks of intravenous antibiotics which was confirmed by blood culture, echocardiographic, and CT imaging. Endocarditis prophylaxis for future at-risk procedures was explained in detail to the patient and his relatives to prevent second infection of implanted device.

SVA are due to inherent aortic medial abnormality, hence the adjacent areas of the RSOV may be diseased and there can be multiple sites of rupture [3]. While endothelialization over the device can scaffold the weak medial tissue, failure of complete or proper endothelialization can leave weak margins and risk of future rupture [3]. On the other hand, an oversized device can lead to problems [3]. RSOV device closure is contra-indicated in more than mild aortic regurgitation [3]. The challenge of transcatheter closures to match surgical results remain, which may give rise to ethical issues until randomized controlled trials with long-term follow-up are available, and needs detailed informed consent from patients. Yet, isolated RSOV has been reported to undergo device closure successfully in specific patient groups which has been reconfirmed in this case report [3]. Our patient has been followed up for 6 months without complications; longer follow-up (median 42 months) with favorable results have also been published [3].

Conclusion

RSOV secondary to native valve IE can occur in apparently healthy young individuals with no predisposing factor. As per our knowledge this is the first ever reported case of documented definitive IE by S. aureus causing Sakakibara and Konno ruptured Type IV SVA that has been successfully managed by device closure. This report can pave the way to further research regarding the role of device closure in such settings as an alternative to surgical option.

Video 1 2-D, color Doppler and 3-D echocardiography showing the 9 mm RSOV aneurysm between NCS and RA along with the 5 × 6 mm vegetation on NCC.

2-D, 2-dimensional; 3-D, 3- dimensional; NCC, non-coronary cusp; NCS, non-coronary sinus; RA, right atrium; RSOV, ruptured sinus of Valsalva.

Video 2 Cardiac catheterization showing aortic root angiography to delineate the RSOV aneurysm for device closure, positioning of the 12 mm ADO II, and deployment of the same device.

ADO, Amplatzer duct occluder; RSOV, ruptured sinus of Valsalva.

Declaration of Competing Interest

None declared

Acknowledgments

Funding

None

Disclosures

The authors have no relationship with industry

Acknowledgment

None

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.jccase.2021.11.007.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Vautrin E, Barone-Rochette G, Philippe J. Rupture of right sinus of valsalva into right atrium: Ultrasound, magnetic resonance, angiography and surgical imaging. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2008;101:501–502. doi: 10.1016/j.acvd.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vereckei A, Vándor L, Halász J, Karádi I, Lengyel M. Infective endocarditis resulting in rupture of sinus of Valsalva with a rupture site communicating with both the right atrium and right ventricle. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2004;17:995–997. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2004.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mahimarangaiah J, Chandra S, Subramanian A, Srinivasa KH, Usha MK, Manjunath CN. Transcatheter closure of ruptured sinus of Valsalva: Different techniques and mid-term follow-up. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2016;87:516–522. doi: 10.1002/ccd.26107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sakakibara S, Konno S. Congenital aneurysm of the sinus of Valsalva anatomy and classification. Am Heart J. 1962;63:405–424. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(62)90287-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Habib G, Lancellotti P, Antunes MJ, Bongiorni MG, Casalta JP, Del Zotti F, Dulgheru R, G El Khoury, Erba PA, Iung B, Miro JM, Mulder BJ, Plonska-Gosciniak E, Price S, Roos-Hesselink J, et al. ESC Guidelines for the management of infective endocarditis: The Task Force for the Management of Infective Endocarditis of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Endorsed by: European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS), the European Association of Nuclear Medicine (EANM) Eur Heart J. 2015;36:3075–3128. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv319. 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Diwakar A, Patnaik SS, Hiremath CS, Chalam KS, Dash P. Rupture of sinus of Valsalva – a 15 years single institutional retrospective review: Preoperative heart failure has an impact on post operative outcome? Ann Card Anaesth. 2019;22:24–29. doi: 10.4103/aca.ACA_243_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chu SH, Hung CR, How SS, Chang H, Wang SS, Tsai CH, Liau CS, Tseng CD, Tseng YZ, Lee YT, Lien WP, Lue HC, Lin TY. Ruptured aneurysms of the sinus of Valsalva in Oriental patients. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1990;99:288–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Missault L, Callens B, Taeymans Y. Echocardiography of sinus of valsalva aneurysm with rupture into the right atrium. Int J Cardiol. 1995;47:269–272. doi: 10.1016/0167-5273(94)02173-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baddour LM, Wilson WR, Bayer AS, Fowler VG, Jr, Tleyjeh IM, Rybak MJ, Barsic B, Lockhart PB, Gewitz MH, Levison ME, Bolger AF, Steckelberg JM, Baltimore RS, Fink AM, O'Gara P, et al. Infective endocarditis in adults: diagnosis, antimicrobial therapy, and management of complications: a scientific statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015;132:1435–1486. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li SJ, Sexton DJ, Mick N, Nettles R, Fowler VG, Jr, Ryan T, Bashore T, Corey GR. Proposed modifications to the Duke criteria for the diagnosis of infective endocarditis. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30:633–638. doi: 10.1086/313753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.