Abstract

The activation of the immune system upon infection exerts a huge energetic demand on an individual, likely decreasing available resources for other vital processes, like reproduction. The factors that determine the trade-off between defensive and reproductive traits remain poorly understood. Here, we exploit the experimental tractability of the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster to systematically assess the impact of immune system activation on pre-copulatory reproductive behaviour. Contrary to expectations, we found that male flies undergoing an immune activation continue to display high levels of courtship and mating success. Similarly, immune-challenged female flies remain highly sexually receptive. By combining behavioural paradigms, a diverse panel of pathogens and genetic strategies to induce the fly immune system, we show that pre-copulatory reproductive behaviours are preserved in infected flies, despite the significant metabolic cost of infection.

Keywords: reproductive behaviours, reproduction and immunity trade-off, bacterial infection, Drosophila, courtship

1. Introduction

Life-history theory argues that there is a trade-off between energetically expensive traits, like reproduction and immunity [1]. Animals expend a considerable amount of energy in pre-copulatory traits, such as courtship behaviours to attract a potential mate or post-copulatory traits, like producing eggs [1]. At the same time, when challenged with an infection, individuals must allocate resources to mount an effective immune response and increase the chances of survival [2,3]. How do individuals prioritize and balance their investment in reproduction and immune defence? Several studies have shown that individuals exposed to harmful infections prioritize defence over reproductive strategies [4,5]. For instance, upon infection, some insects and birds show decreased egg production [6], whereas infected crickets and fish show reduced sperm production and viability [7]. Further, time invested in courtship and overall performance is affected in response to infection in birds and fish [8,9]. On the other hand, studies in several species have indicated increased reproductive effort during infection [10,11]. The selection between investment strategies is thought to depend on the host's internal conditions (e.g. age and genetic background) [12,13] and extrinsic factors (e.g. nature of the infection, pathogen's virulence and its relationship with the host) [14]. Therefore, investigating how the infection type, dose, timing and virulence modulate reproductive traits is essential for understanding variation in reproductive effort across species.

Drosophila melanogaster is a powerful model organism to study the interaction between reproduction and immunity. First, the courtship ritual in flies is composed of complex innate behaviours that culminate with copulation and has been studied for more than 100 years [15]. To woo a female and assess her suitability, male flies perform a sequence of stereotyped courtship steps that allow the exchange of sensory cues. Females show acceptance or rejection behaviours in response to the male's courtship display [15]. Second, Drosophila has a well-characterized immune system [16]. While a hallmark of the immune activation is the synthesis of antimicrobial peptides (AMPs), it is characterized by a marked transcriptomic switch with a profound metabolic impact [17]. These changes take place primarily in the fat body and are under the control of two different cascades: Toll and Imd pathways, which activate different NF-κB-like factors and induce the innate immune response [16]. Notably, many aspects of innate immunity are conserved between flies and mammals, such as NF-κB family transcription factors and signal transduction pathways, and the organization of the immune system is highly analogous [16]. A few studies have investigated the impact of pathogen infection on female reproductive traits, like oviposition [18], and some aspects of male courtship [19]. However, how infection modulates reproductive behaviours in Drosophila remains poorly understood.

Here, we systematically assess the impact of infections with pathogenic and non-pathogenic bacterial species on male courtship behaviours and female sexual receptivity in D. melanogaster. We evaluate bacterial strains that are phylogenetically diverse, have different virulence and host–pathogen relationships and impose differing fitness costs on flies [20–23]. Our findings indicate that male courtship behaviours, female sexual receptivity and mating success are safeguarded during bacterial infections. Moreover, reproductive behaviours remain unaltered upon genetic activation of Toll and Imd immune pathways. Our study demonstrates that pre-copulatory reproductive behaviours remain preserved in infected flies despite the significant metabolic cost of infection.

2. Material and methods

Also see extended methods.

(a) . Drosophila stocks

Wild-type D. melanogaster lines used in the study include Canton-S and Dahomey strains. Transgenic lines include C564-GAL4 (BDSC 6982), UAS-Toll10B (BDSC 58987) and UAS-Imd (gift from Markus Knaden). Flies were raised on a standard cornmeal at 25°C, 50–60% humidity with a 12 h light/dark cycle. Virgin male and female flies were aged for 5–7 days in same-sex groups of 15–20 before experimentation.

(b) . Bacterial infection

The bacterial strains used in this study include Serratia marcescens (DB11), Staphylococcus aureus (SH1000), Listeria monocytogenes (EGD-e), Escherichia coli (DH5α), Pectinobacterium carotovorum carotovorum 15 (ECC15) and Micrococcus luteus (clinical isolate, gift from Prof. William Wade, King's College London). The bacterial strains were cultured overnight (see extended methods) at and cultures were pelleted by centrifugation at 4500g for 2 min. The pellet was diluted in filter-sterilized phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to a defined concentration. Fifty nanolitres of the diluted bacterial solution was injected employing a nano-injector (MPP1-3 Pressure Injector, Applied Scientific Instrumentation) into the abdomen of anaesthetized flies as per [24].

(c) . Survival assay

Infected flies and controls were placed in groups of 10–15 in.vials at 29°C. The number of live flies infected with pathogenic strains was counted at regular intervals until all the infected flies were dead. Flies injected with non-pathogenic strains were counted at regular intervals for 72 h.

(d) . Behavioural assays and parameters

All behavioural experiments were done in between zeitgeber time (ZT01) and (ZT10) at 25°C. Mating assays were carried out in courtship chambers (20 mm in diameter and 5 mm in height), which have built-in dividers that allow separation of the flies before the experiment. For single pair mating assay, flies were injected with bacteria or vehicle solution (PBS) and immediately placed in the courtship chamber with food. Before the behavioural measurement began, the uninfected flies of the opposite sex were introduced using a fly aspirator. The dividers were opened before the assay and behaviours were recorded for 1 h. For mate choice assays, a focal fly was given a choice between an infected and a healthy (PBS) mate. The infected and healthy flies were marked with acrylic paint 48 h before experimentation. After injection, both infected and PBS flies were transferred to a courtship chamber with food. The focal fly was aspirated into the chamber before behavioural experimentation and behaviours were recorded for 1 h. Courtship index (in experiments with infected males and controls) was measured as the proportion of time the male spends courting from the beginning of courtship until 10 min or end of copulation. Mating success was measured as the percentage of flies that mated within 1 h. Copulation latency (in experiments with infected females and controls) was measured as the time taken to copulate from the start of courtship. For competitive mating assays, the focal fly's first mate choice was recorded (i.e. if the fly chose to mate with a healthy or infected mate).

(e) . Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses and data visualization (ggplot2, R Markdown) were performed using R studio (R v. 3.6). We used mixed effect regression models to explore the effect of infection timing and concentration on male courtship behaviours. Kruskal–Wallis followed by Dunn's test with Bonferroni corrections were used for post hoc comparisons across different treatments. Fisher's exact test was used to analyse count data and log-rank test for survival data. Differences were accepted as significant at p < 0.05. Statistical analysis and sample sizes are summarized in the electronic supplementary material.

3. Results

(a) . Male courtship behaviour is maintained during infections with non-pathogenic bacteria

To reliably produce infection phenotypes and assess the consequences in behaviour, we used a nano-injector to deliver precise volumes of bacterial solution into the abdomen of wild-type Canton S (CS) flies [24]. As a starting point, we chose three different non-pathogenic bacteria: ECC15, E. coli and M. luteus, which activate the fly's innate immune system without affecting lifespan [21,25,26]. Gram-negative bacteria ECC15 and E. coli induce the Imd pathway, while the Gram-positive bacterium M. luteus activates the Toll pathway [16]. As expected, CS males infected with either ECC15, E. coli or M. luteus showed a survival rate similar to that of uninfected and sham-infected flies (electronic supplementary material, figure S1A–C). Given that flies rapidly clear non-pathogenic bacteria from their bodies [21,27], we measured behaviour 5–6 h post-infection, when the bacterial load is still detectable and the immune activation is robust.

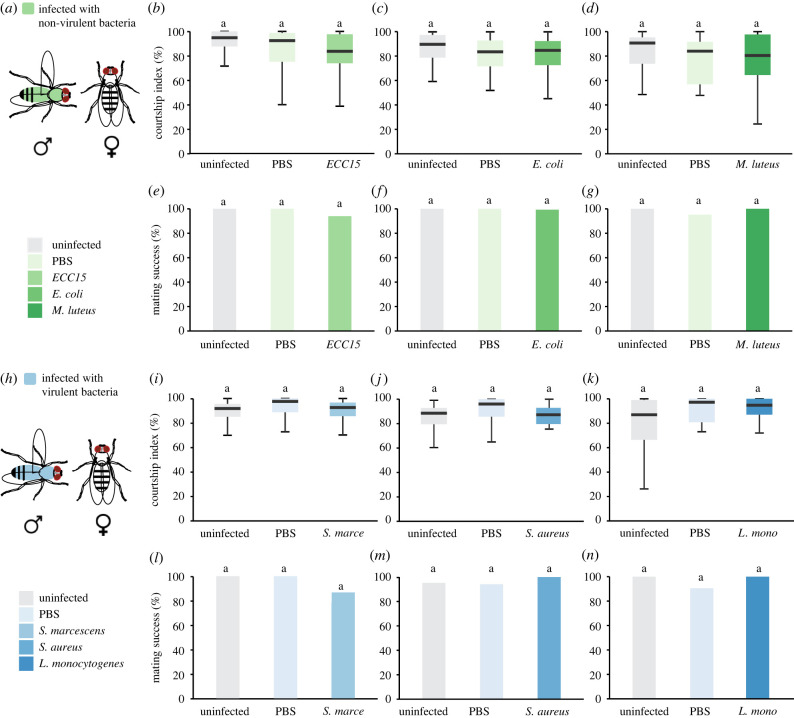

To assess the effects of non-pathogenic bacteria on male courtship, we performed single mating assays, where an infected male was paired with a healthy virgin female (figure 1a). As expected, uninfected and sham-infected males (PBS) spent most of the time courting the female. Interestingly, males infected with either ECC15, E. coli or M. luteus displayed comparable courtship levels to that of controls (figure 1b–d). Most control males successfully copulated within 1 h and infected males showed a similar rate of copulation (figure 1e–g). To further explore the trade-off between male courtship behaviours and immune activation, we evaluated the behaviour of ECC15 infected flies at three different time points (3, 5 and 8 h) and doses (OD600 = 0.5, 1 and 2) (electronic supplementary material, figure S2). Earlier or later time points, as well as changes in the bacterial load, did not reveal a change in male courtship behaviour or mating success (electronic supplementary material, figure S2).

Figure 1.

Effect of bacterial infections on male courtship behaviour. (a,h) Male CS flies were injected with three non-pathogenic (a) and pathogenic (h) strains and tested in a single pair courtship assay with an uninfected virgin female. (b) Courtship index and (e) mating success of males infected with ECC15 and their respective controls (n = 31–32). (c) Courtship index and (f) mating success of males infected with E. coli and their respective controls (n = 22–31). (d) Courtship index and (g) mating success of males infected with M. luteus and their respective controls (n = 21–22). (i) Courtship index and (l) mating success of males infected with S. marcescens and their respective controls (n = 29–30). (j) Courtship index and (m) mating success of males infected with S. aureus and their respective controls (n = 17–21). (k) Courtship index and (n) mating success of males infected with L. monocytogenes and their respective controls (n = 20–23). Dunn's test in (b–d), (i–k) and Fisher's test in (e–g), (l–n). Courtship indices and mating success are presented as percentage. A detailed description of the statistics employed can be found in the electronic supplementary material. (Online version in colour.)

Next, we asked if the lack of effect of infection on male courtship could be generalized to a second Drosophila wild-type strain. To this end, we selected Dahomey, an outbred strain isolated from Benin [28]. We found that, like CS, Dahomey males did not alter their courtship behaviour in response to infection (electronic supplementary material, figure S3). These results suggest that male courtship behaviours are maintained during the response to non-pathogenic infections.

(b) . Wild-type males sustain courtship behaviour during pathogenic and lethal infections

Our findings show that male courtship behaviours are not affected by infections with non-pathogenic strains. We reasoned that more virulent and pathogenic bacteria that can grow within the flies may have a stronger impact on male pre-copulatory behaviours. To test this hypothesis, we chose three pathogenic bacterial species that have been shown to negatively affect Drosophila physiology and induce lethality: S. marcescens, S. aureus and L. monocytogenes (figure 1h). Infecting male flies with the natural insect pathogen S. marcescens caused 100% mortality within 9 h upon injection (electronic supplementary material, figure S1D). By contrast, uninfected flies and sham-infected flies survived through the observation time. Non-natural pathogens for flies, such as S. aureus or L. monocytogenes, induced lethality within 24 h (electronic supplementary material, figure S1E) and approximately 7 days (electronic supplementary material, figure S1F), respectively, as previously reported [20,21,23].

Considering the survival data, we performed behavioural experiments with S. marcescens, S. aureus and L. monocytogenes at 5–6 h, 8–9 h and 24–25 h post-infection, respectively, when the immune response is mounted, and the infections are advanced but not too detrimental for the flies (e.g. locomotion abilities remain intact; electronic supplementary material, figure S4). Surprisingly, none of these lethal infections altered male courtship behaviour. There were no significant changes in the courtship index of infected males with either S. marcescens (figure 1i), S. aureus (figure 1j) or L. monocytogenes (figure 1k). Further, these lethal infections did not compromise male mating success (figure 1l–n). To investigate if additional infection timings might reveal a trade-off between defensive and pre-copulatory behaviours, we tested S. marcescens infected males at earlier (4–5 h) and later (6–7 h) time points. While we did not find changes 4 h post-infection, we detected a significant decrease in courtship index and mating success 6 h post-infection in infected males (electronic supplementary material, figure S5B,C). However, these flies were lethargic and presented a drastic reduction of locomotor activity (electronic supplementary material, figure S5D–F), arguing for an unspecific effect on pre-copulatory behaviours. Selection might favour flies that do not increase immune investment as there is no chance to overcome the infection. We thus asked if lower doses of S. marcescens would reveal an effect of infection on courtship. We thus tested two more infections doses of this bacteria (OD600 = 0.01 and OD600 = 0.001). While the lower doses extended lifespan (electronic supplementary material, figure S6A), there was still no effect on pre-copulatory behaviours (electronic supplementary material, figure S6C,D). Finally, the courtship behaviours of Dahomey male flies infected with any of these pathogenic bacterial strains remained unaffected (electronic supplementary material, figure S3).

Altogether, male courtship behaviours seem unaltered during bacterial infections, even in the face of a life-threatening situation. We reasoned that the high level of sex drive observed in control flies (figure 1) might mask the modulatory effect of immune activation. To decrease basal courtship levels, we presented CS males with mated females, which are reluctant to copulate and are therefore unattractive courtship targets [29]. As expected, uninfected CS males showed decreased courtship index towards mated females (approx. 20%). However, when presented with mated females, male flies infected with either pathogenic (S. marcescens) or non-pathogenic (ECC15, M. luteus) bacteria exhibited similar courtship behaviour to that of controls (PBS or uninjected) (electronic supplementary material, table S1).

From our experiments, we conclude that CS and Dahomey males infected with either pathogenic or non-pathogenic strains maintain their courtship efforts while they mount a costly immune response.

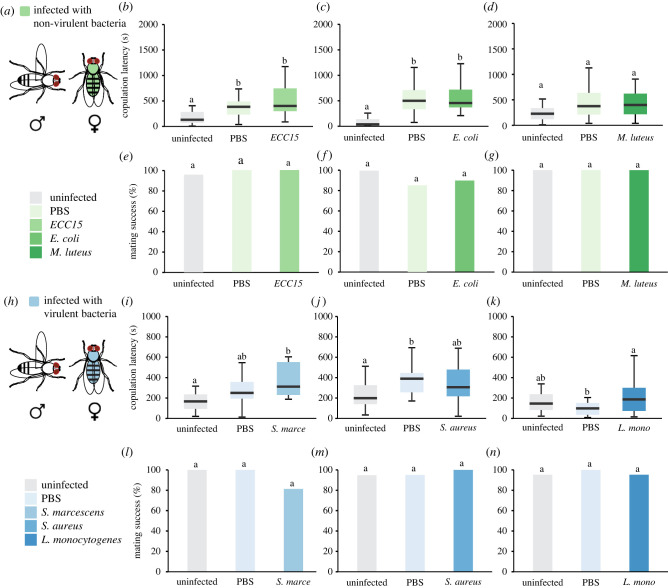

(c) . Female flies sustain their sexual receptivity during bacterial infections

In many animals, including flies, there is sexual dimorphism in survival, pathology, bacterial load and activity in response to infections [30,31]. In addition, the costs of reproduction might be different between sexes. Hence, we asked if female reproduction behaviour is differentially modulated by infections. We injected CS and Dahomey virgin females with the same non-pathogenic (figure 2a) and pathogenic (figure 2h) bacteria we employed for males and measured copulation latency and mating success, both of which are proxies for female receptivity. For the non-pathogenic bacteria, we found that both infected and sham-infected females exhibit a higher latency to copulation than uninfected controls. However, there were no differences between sham-infected and infected females, indicating that bacterial infection itself does not influence copulation latency (figure 2b–d). Similarly, female mating success remained unchanged upon infection with non-pathogenic bacteria (figure 2e–g). The pathogenic strains dramatically reduced female survival (electronic supplementary material, figure S1D–F); however, these infections did not affect the latency to copulation in females (figure 2i–k). In addition, female mating success remained unaffected upon pathogenic infection (figure 2l–n). Dahomey virgin females infected with all these bacteria strains showed a similar trend (electronic supplementary material, figure S7). We therefore conclude that Drosophila female receptivity is not affected during the response to infections.

Figure 2.

Effect of bacterial infections on female sexual receptivity. (a,h) Virgin female CS flies were injected with three different non-pathogenic (a) and pathogenic (h) strains and tested in a single pair courtship assay with an uninfected male. (b) Copulation latency and (e) mating success of females infected with ECC15 and their respective controls (n = 20–24). (c) Copulation latency and (f) mating success of females infected with E. coli and their respective controls (n = 19–20). (d) Copulation latency and (g) mating success of males infected with M. luteus and their respective controls (n = 31–32). (i) Copulation latency and (l) mating success of females infected with S. marcescens and their respective controls (n = 16–19). (j) Copulation latency and (m) mating success of females infected with S. aureus and their respective controls (n = 19–20). (k) Copulation latency and (n) mating success of females infected with L. monocytogenes and their respective controls (n = 20–21). Dunn's test in (b–d), (i–j) and Fisher's test in (e–g), (l–n). Copulation latency is measured in seconds and mating success is presented as percentage. A detailed description of the statistics employed can be found in the electronic supplementary material. (Online version in colour.)

(d) . Effect of social context on pre-copulatory behaviours under infection conditions

Male reproductive behaviours are modulated by social context [32]. We thus wondered whether infected male flies would behave differently in the presence of a healthy male competitor. To test this, we paired a CS virgin female with a healthy male and a male infected with S. aureus (figure 3a). Interestingly, we found that infected males with this pathogenic strain courted to the same extent as the uninfected male (figure 3b). In addition, healthy females did not preferentially mate with healthy males over infected males (figure 3c). We similarly tested whether healthy male flies would behave differently towards healthy or infected females (figure 3d). When given a simultaneous choice between S. aureus-infected females and sham-infected females, these males spent a similar amount of time courting each female in a competitive assay (figure 3e). Moreover, they mated equally with healthy or S. aureus-infected females (figure 3f). Extending these studies to a second pathogenic strain, S. marcescens, showed an identical pattern (figure 3g–l). These results suggest that a more complex social context does not change the reproductive performance of infected flies.

Figure 3.

Effect of pathogenic infections on courtship behaviours and mate selection in a choice context. (a) A focal female was given a choice between a male injected with PBS and a male infected with S. aureus. (b) Courtship index of the PBS or infected male towards the focal female. (c) Female's first mate choice (n = 57). (d) A focal male was given a choice between a PBS female and a female infected with S. aureus. (e) Courtship index of the focal male. (f) Male's first mate choice (n = 45). (g) A focal female was given a choice between a PBS male and a male infected with S. marcescens. (h) Courtship index of the PBS or infected male. (i) Female's first mate choice (n = 38). (j) A focal male was given a choice between a PBS female and a female infected with S. marcescens. (k) Courtship index of the focal male towards PBS or infected female. (l) Male's first mate choice (n = 54). Wilcoxon's test in (b), (e), (h) and (k) and Fisher's test in (c), (f), (i) and (l). Courtship indices and first choice are presented as percentage. A detailed description of the statistics employed can be found in the electronic supplementary material. (Online version in colour.)

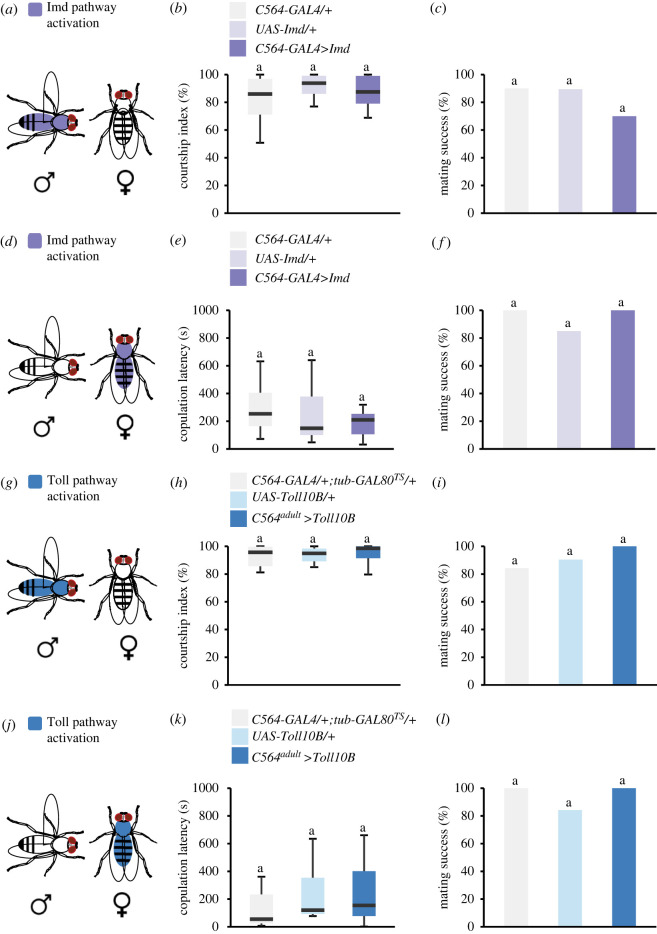

(e) . Genetic activation of the immune pathways has limited impact on male courtship behaviour and female sexual receptivity

We next inquired if a strong genetic induction of the immune system without the presence of bacteria would affect the pre-copulatory behaviours shown by flies. To trigger each of the Drosophila immune arms in a specific manner, we genetically activated the immune pathways in the fat body, the primary site of humoral immune response, using the GAL4/UAS system [33]. To achieve this, we overexpressed Imd [34] or Toll10B [35,36] using C564-GAL4 that targets the fat body and a few other tissues (e.g. gut and reproductive tract [37]). We found that constitutive activation of the Imd pathway does not significantly alter the courtship index or mating success in C564 > Imd males (figure 4a–c). Similarly, the activation of the Imd pathway did not influence female copulation latency or mating success (figure 4d–f).

Figure 4.

Effect of immune system activation on male courtship behaviour. (a,d) The Imd pathway was artificially activated in the fat body of male or virgin female flies. (b–c) Courtship index and mating success of C564-GAL4 > UAS-Imd male flies (n = 19–20). (e,f) Copulation latency and mating success of C564-GAL4 > UAS-Imd female flies (n = 20–24). (g,j) Toll pathway was artificially activated in fat bodies of male or virgin female flies in an adult-specific way. (h–i) Courtship index and mating success of C564-GAL4; tub-GAL80TS>UAS-Toll10B male flies (n = 19–21). (k,l) Copulation latency and mating success of C564-GAL4; tub-GAL80TS > UAS-Toll10B female flies (n = 19–20). Dunn's test in (b), (e), (h) and (k), Fisher's test in (c), (f), (i) and (l). Copulation latency is measured in seconds; courtship indices and mating success are presented as percentage. A detailed description of the statistics employed can be found in the electronic supplementary material. (Online version in colour.)

We next tested the effects of activation of the Toll pathway. Since the expression of Toll10B inhibits growth and causes developmental defects [38], we expressed Toll10B in an adult-specific way. We combined C564-GAL4 with the temperature-sensitive tub-GAL80ts (GAL80ts) [39], an inhibitor of GAL4. At high temperature, GAL80 ceases to suppress GAL4, thereby allowing the expression of Toll10B. Intriguingly, we found that adult-specific activation of Toll10B using the TARGET system did not affect the courtship index or mating success in C564-GAL4; tub-GAL80ts>UAS-Toll10B males when compared to controls (figure 4g–i). Furthermore, female sexual behaviour was unaffected in C564-GAL4; tub-GAL80ts>UAS-Toll10B females (figure 4j–l). These results, together with our previous findings, demonstrate that the activation of the immune system does not affect pre-copulatory behaviours in Drosophila.

4. Discussion

Reproduction and immunity are intricately linked traits central to an animal's fitness [1]. The factors that determine the trade-off between these energetically expensive traits remain poorly understood [1]. Here, we carried out detailed analyses of the effect of bacterial infections on pre-copulatory behaviours in D. melanogaster. We systematically tested the behavioural impact of infections with pathogenic (S. marcescens, S. aureus and L. monocytogenes) and non-pathogenic species (Erwinia carotovora carotovora 15, E. coli and M. luteus), using different bacterial doses, infection time points, and fly social contexts.

Our findings show that males infected with these diverse bacterial strains show normal levels of courtship intensity and mating success, even when presented with unfavourable targets. Further, females subjected to the same bacterial infections display high sexual receptivity and mating success. Consistent with our study, Keesey et al. [19] showed that infection with the lethal pathogen Pseudomonas entomophila leads to a small decrease in mating success in flies. Crucially, we report that generalized, constitutive and strong activation of the immune pathways by genetic means does not influence male or female pre-copulatory behaviours. These observations suggest that the preservation of pre-copulatory behaviours upon bacterial infection is not strain or doses specific but rather a general response in flies.

To optimize their fitness, animals are likely to avoid mating with partners infected with pathogens [40,41]. Birds and rodents have shown to discriminate against infected mates [40]. For example, greenfinches with a coccidian infection display reduced plumage coloration, reducing their chances of being selected as mates [42]. By contrast, our study shows that healthy and infected flies with S. marcescens and S. aureus pathogenic strains are equally chosen as patterns in competitive mating assays.

Importantly, our finding that Drosophila pre-copulatory behaviours are preserved during infections has parallels in other species. For instance, frogs infected with a deadly pathogen have comparable calling properties to that of uninfected individuals [43]. In addition, the immune activation by LPS injection in male crickets Teleogryllus commodus or Gryllodes sigillatus does not impact pre-copulatory traits [44,45]. To maintain pre-copulatory traits intact through the infection, immune-challenged flies may invest more of their available resources in reproduction, making a terminal investment [46]. However, while we observed a preservation of pre-copulatory behaviours, we did not find an increased expression of these reproductive traits.

Different reproductive traits may vary in their response to infections. For instance, Drosophila mated females reduce the rate of egg-laying in response to E. coli infection or exposure to LPS, likely decreasing the infection risk of their progeny [18]. Drosophila males infected with P. aeruginosa, display a decrease in sperm viability [47]. A reduced investment in post-copulatory traits but not in the execution of courtship behaviours could be explained by differential energetic costs associated with these traits. Post-copulatory traits, like sperm viability, ovulation and oviposition, might be energetically more expensive and therefore be under stronger selection pressure.

Several of the treatments employed in this study, such as L. monocytogenes or E. coli infections and genetic activation of the Toll pathway in the fat body, have been shown to interfere with the insulin signalling pathway and subsequently decrease nutrient storage or growth [27,38,48]. Yet, despite the marked metabolic switch triggered during systemic infections, flies retain their pre-copulatory behaviours. These findings highlight the relevance of reproductive behaviours and raise the question as to what mechanisms are in place to preserve them. Are the neuronal clusters or tissues dedicated to courtship insensitive to the systemic transformations triggered by infection? Conversely, are there mechanisms in place that actively maintain behavioural performance in response to infection-induced signals? The molecular and cellular machineries that control pre-copulatory behaviours upon bacteria detection remain to be determined.

It is important to highlight that systemic infections affect several non-reproductive behaviours in Drosophila. For instance, upon ingesting food contaminated with bacteria, flies reduce their activity and avoid harmed food via conditioned taste aversion mechanisms [49]. Moreover, upon contacting chemicals that normally activate the immune system, flies increase hygienic grooming [50]. Further, there is an interplay between immune activation and locomotion, with a subsequent impact on sleep, which depends on the pathogen type, the context and life history of the host [51]. Recently, it was reported that the Toll pathway in the fat body mediates a decrease in sleep in males infected with M. luteus [52]. By contrast, flies infected with S. pneumoniae show normal levels of activity but display altered sleep architecture and circadian rhythms [53].

In conclusion, despite the profound impact of bacterial infections on numerous metabolic, physiological and behavioural traits in Drosophila, pre-copulatory behaviours remain preserved, even in the face of deadly pathogens. Future experiments will investigate the mechanisms and the evolutionary ramifications of such strategy prioritization.

Acknowledgements

We thank Jean-Christophe Billeter and Joanne Yew for helpful discussions. We are grateful to Bruno Lemaitre and Markus Knaden for sharing fly stocks or bacterial strains with us. We would like to thank Shaleen Glasgow for help with fly collections and Laurie Cazale-Debat for providing schematics. Finally, we thank the members of the Rezaval and Dionne lab for helpful discussions.

Data accessibility

The raw data and R code used for analysis has been deposited at Dryad: https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.76hdr7szw [54].

The data are provided in the electronic supplementary material [55].

Authors' contributions

S.R.: conceptualization, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, writing—original draft and writing—review and editing; E.J.B.: conceptualization, writing—original draft and writing—review and editing; C.B.: formal analysis and investigation; R.C.M.: resources and writing—review and editing; M.S.D.: resources and writing—review and editing; C.R.: conceptualization, funding acquisition, methodology, project administration, resources, supervision, writing—original draft and writing—review and editing.

All authors gave final approval for publication and agreed to be held accountable for the work performed therein.

Conflict of interest declaration

We declare we have no competing interests.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from BBSRC (grant no. BB/S009299/1), Wellcome Trust (grant no. 214062/Z/18/Z) and Royal Society Research (grant no. RGS/R2/180272) to C.R., and a Darwin studentship to S.R. E.J.B. is supported by an IBRO Return Home Fellowship 2020.

References

- 1.Stearns SC. 1989. Trade-offs in life-history evolution. Funct. Ecol. 3, 259. ( 10.2307/2389364) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cotter SC, Simpson SJ, Raubenheimer D, Wilson K. 2011. Macronutrient balance mediates trade-offs between immune function and life history traits. Funct. Ecol. 25, 186-198. ( 10.1111/j.1365-2435.2010.01766.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lochmiller RL, Deerenberg C. 2000. Trade-offs in evolutionary immunology: just what is the cost of immunity? Oikos 88, 87-98. ( 10.1034/j.1600-0706.2000.880110.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gustafsson L, Nordling D, Andersson MS, Sheldon BC, Qvarnström A, Hamilton WD, Howard JC. 1994. Infectious diseases, reproductive effort and the cost of reproduction in birds. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 346, 323-331. ( 10.1098/rstb.1994.0149) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adamo SA, Jensen M, Younger M. 2001. Changes in lifetime immunocompetence in male and female Gryllus texensis (formerly G. integer): trade-offs between immunity and reproduction. Anim. Behav. 62, 417-425. ( 10.1006/anbe.2001.1786) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schwenke RA, Lazzaro BP, Wolfner MF. 2016. Reproduction–immunity trade-offs in insects. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 61, 239-256. ( 10.1146/annurev-ento-010715-023924) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wigby S, Suarez SS, Lazzaro BP, Pizzari T, Wolfner MF. 2019. Sperm success and immunity. In Current topics in developmental biology, pp. 287-313. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kolluru GR, Grether GF, Dunlop E, South SH. 2009. Food availability and parasite infection influence mating tactics in guppies (Poecilia reticulata). Behav. Ecol. 20, 131-137. ( 10.1093/beheco/arn124) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chargé R, Saint Jalme M, Lacroix F, Cadet A, Sorci G. 2010. Male health status, signalled by courtship display, reveals ejaculate quality and hatching success in a lekking species. J. Anim. Ecol. 79, 843-850. ( 10.1111/j.1365-2656.2010.01696.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.An D, Waldman B. 2016. Enhanced call effort in Japanese tree frogs infected by amphibian chytrid fungus. Biol. Lett. 12, 20160018. ( 10.1098/rsbl.2016.0018) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Velando A, Drummond H, Torres R. 2006. Senescent birds redouble reproductive effort when ill: confirmation of the terminal investment hypothesis. Proc. R. Soc. B 273, 1443-1448. ( 10.1098/rspb.2006.3480) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Copeland EK, Fedorka KM. 2012. The influence of male age and simulated pathogenic infection on producing a dishonest sexual signal. Proc. R. Soc. B 279, 4740-4746. ( 10.1098/rspb.2012.1914) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duffield KR, Hampton KJ, Houslay TM, Hunt J, Rapkin J, Sakaluk SK, Sadd BM. 2018. Age-dependent variation in the terminal investment threshold in male crickets. Evol. Int. J. Org. Evol. 72, 578-589. ( 10.1111/evo.13443) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duffield KR, Bowers EK, Sakaluk SK, Sadd BM. 2017. A dynamic threshold model for terminal investment. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 71, 185. ( 10.1007/s00265-017-2416-z) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ellendersen BE, von Philipsborn AC.. 2017. Neuronal modulation of D. melanogaster sexual behaviour. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 24, 21-28. ( 10.1016/j.cois.2017.08.005) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lemaitre B, Hoffmann J. 2007. The host defense of Drosophila melanogaster. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 25, 697-743. ( 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141615) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dionne M. 2014. Immune-metabolic interaction in Drosophila. Fly (Austin) 8, 75-79. ( 10.4161/fly.28113) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kurz CL, Charroux B, Chaduli D, Viallat-Lieutaud A, Royet J. 2017. Peptidoglycan sensing by octopaminergic neurons modulates Drosophila oviposition. eLife 6, e21937. ( 10.7554/eLife.21937) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keesey IW, Koerte S, Khallaf MA, Retzke T, Guillou A, Grosse-Wilde E, Buchon N, Knaden M, Hansson BS. 2017. Pathogenic bacteria enhance dispersal through alteration of Drosophila social communication. Nat. Commun. 8, 265. ( 10.1038/s41467-017-00334-9) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mansfield BE, Dionne MS, Schneider DS, Freitag NE. 2003. Exploration of host–pathogen interactions using Listeria monocytogenes and Drosophila melanogaster. Cell Microbiol. 5, 901-911. ( 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2003.00329.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Duneau D, Ferdy JB, Revah J, Kondolf H, Ortiz GA, Lazzaro BP, Buchon N. 2017. Stochastic variation in the initial phase of bacterial infection predicts the probability of survival in D. melanogaster. eLife 6, e28298. ( 10.7554/eLife.28298) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nehme NT, Liégeois S, Kele B, Giammarinaro P, Pradel E, Hoffmann JA, Ewbank JJ, Ferrandon D. 2007. A model of bacterial intestinal infections in Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS Pathog. 3, e173. ( 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030173) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Needham AJ, Kibart M, Crossley H, Ingham PW, Foster SJ. 2004. Drosophila melanogaster as a model host for Staphylococcus aureus infection. Microbiol. Read. Engl. 150, 2347-2355. ( 10.1099/mic.0.27116-0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dionne MS, Ghori N, Schneider DS. 2003. Drosophila melanogaster is a genetically tractable model host for Mycobacterium marinum. Infect. Immun. 71, 3540-3550. ( 10.1128/IAI.71.6.3540-3550.2003) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lemaitre B, Reichhart JM, Hoffmann JA. 1997. Drosophila host defense: differential induction of antimicrobial peptide genes after infection by various classes of microorganisms. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 94, 14 614-14 619. ( 10.1073/pnas.94.26.14614) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shia AKH, Glittenberg M, Thompson G, Weber AN, Reichhart JM, Ligoxygakis P. 2009. Toll-dependent antimicrobial responses in Drosophila larval fat body require Spätzle secreted by haemocytes. J. Cell Sci. 122, 4505-4515. ( 10.1242/jcs.049155) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vincent CM, Dionne MS. 2021. Disparate regulation of IMD signaling drives sex differences in infection pathology in Drosophila melanogaster. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2026554118. ( 10.1073/pnas.2026554118) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bass TM, Grandison RC, Wong R, Martinez P, Partridge L, Piper MDW. 2007. Optimization of dietary restriction protocols in Drosophila. J. Gerontol. Ser. A 62, 1071-1081. ( 10.1093/gerona/62.10.1071) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ejima A, Smith BPC, Lucas C, van der Goes van Naters W, Miller CJ, Carlson JR, Levine JD, Griffith LC. 2007. Generalization of courtship learning in Drosophila is mediated by cis-vaccenyl acetate. Curr. Biol. 17, 599-605. ( 10.1016/j.cub.2007.01.053) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Belmonte RL, Corbally MK, Duneau DF, Regan JC. 2020. Sexual dimorphisms in innate immunity and responses to infection in Drosophila melanogaster. Front. Immunol. 10, 3075. ( 10.3389/fimmu.2019.03075) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nunn CL, Lindenfors P, Pursall ER, Rolff J. 2009. On sexual dimorphism in immune function. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 364, 61-69. ( 10.1098/rstb.2008.0148) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lizé A, Doff RJ, Smaller EA, Lewis Z, Hurst GDD. 2012. Perception of male–male competition influences Drosophila copulation behaviour even in species where females rarely remate. Biol. Lett. 8, 35-38. ( 10.1098/rsbl.2011.0544) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brand AH, Perrimon N. 1993. Targeted gene expression as a means of altering cell fates and generating dominant phenotypes. Dev. Camb. Engl. 118, 401-415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Buchon N, Broderick NA, Poidevin M, Pradervand S, Lemaitre B. 2009. Drosophila intestinal response to bacterial infection: activation of host defense and stem cell proliferation. Cell Host Microbe 5, 200-211. ( 10.1016/j.chom.2009.01.003) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schneider DS, Hudson KL, Lin TY, Anderson KV. 1991. Dominant and recessive mutations define functional domains of toll, a transmembrane protein required for dorsal–ventral polarity in the Drosophila embryo. Genes Dev. 5, 797-807. ( 10.1101/gad.5.5.797) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maxton-Küchenmeister J, Handel K, Schmidt-Ott U, Roth S, Jäckle H. 1999. Toll homolog expression in the beetle Tribolium suggests a different mode of dorsoventral patterning than in Drosophila embryos. Mech. Dev. 83, 107-114. ( 10.1016/S0925-4773(99)00041-6) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Harrison DA, Binari R, Nahreini TS, Gilman M, Perrimon N. 1995. Activation of a Drosophila Janus kinase (JAK) causes hematopoietic neoplasia and developmental defects. EMBO J. 14, 2857-2865. ( 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07285.x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.DiAngelo JR, Bland ML, Bambina S, Cherry S, Birnbaum MJ. 2009. The immune response attenuates growth and nutrient storage in Drosophila by reducing insulin signaling. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 20 853-20 858. ( 10.1073/pnas.0906749106) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.del Valle Rodríguez A, Didiano D, Desplan C. 2012. Power tools for gene expression and clonal analysis in Drosophila. Nat. Methods 9, 47-55. ( 10.1038/nmeth.1800) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Beltran-Bech S, Richard FJ. 2014. Impact of infection on mate choice. Anim. Behav. 90, 159-170. ( 10.1016/j.anbehav.2014.01.026) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Partridge L. 1980. Mate choice increases a component of offspring fitness in fruit flies. Nature 283, 290-291. ( 10.1038/283290a0) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hõrak P, Saks L, Karu U, Ots I, Surai PF, McGRAW KJ. 2004. How coccidian parasites affect health and appearance of greenfinches. J. Anim. Ecol. 73, 935-947. ( 10.1111/j.0021-8790.2004.00870.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Greenspan SE, Roznik EA, Schwarzkopf L, Alford RA, Pike DA. 2016. Robust calling performance in frogs infected by a deadly fungal pathogen. Ecol. Evol. 6, 5964-5972. ( 10.1002/ece3.2256) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Drayton JM, Boeke JEK, Jennions MD. 2013. Immune challenge and pre- and post-copulatory female choice in the cricket Teleogryllus commodus. J. Insect Behav. 26, 176-190. ( 10.1007/s10905-012-9347-3) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kerr AM, Gershman SN, Sakaluk SK. 2010. Experimentally induced spermatophore production and immune responses reveal a trade-off in crickets. Behav. Ecol. 21, 647-654. ( 10.1093/beheco/arq035) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Clutton-Brock TH. 1984. Reproductive effort and terminal investment in iteroparous animals. Am. Nat. 123, 212-229. ( 10.1086/284198) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Radhakrishnan P, Fedorka KM. 2012. Immune activation decreases sperm viability in both sexes and influences female sperm storage. Proc. R. Soc. B 279, 3577-3583. ( 10.1098/rspb.2012.0654) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chambers MC, Song KH, Schneider DS. 2012. Listeria monocytogenes infection causes metabolic shifts in Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS ONE 7, e50679. ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0050679) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kobler JM, Rodriguez Jimenez FJ, Petcu I, Grunwald Kadow IC. 2020. Immune receptor signaling and the mushroom body mediate post-ingestion pathogen avoidance. Curr. Biol. 30, 4693-4709. ( 10.1016/j.cub.2020.09.022) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yanagawa A, Guigue AMA, Marion-Poll F. 2014. Hygienic grooming is induced by contact chemicals in Drosophila melanogaster. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 8, 254. ( 10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00254) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Williams JA, Sathyanarayanan S, Hendricks JC, Sehgal A. 2007. Interaction between sleep and the immune response in Drosophila: a role for the NFκB relish. Sleep 30, 389-400. ( 10.1093/sleep/30.4.389) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vincent CM, Beckwith EJ, Pearson WH, Kierdorf K, Gilestro G, Dionne MS. 2021. Infection increases activity via Toll dependent and independent mechanisms in Drosophila melanogaster. ( 10.1101/2021.08.24.457493) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 53.Shirasu-Hiza MM, Dionne MS, Pham LN, Ayres JS, Schneider DS. 2007. Interactions between circadian rhythm and immunity in Drosophila melanogaster. Curr. Biol. 17, R353-R355. ( 10.1016/j.cub.2007.03.049) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rose S. 2022. Data from: pre-copulatory reproductive behaviours are preserved in Drosophila melanogaster infected with bacteria. Dryad Digital Repository. ( 10.5061/dryad.76hdr7szw) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 55.Rose S. 2022. Pre-copulatory reproductive behaviours are preserved in Drosophila melanogaster infected with bacteria. FigShare. ( 10.6084/m9.figshare.c.5962396) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Rose S. 2022. Data from: pre-copulatory reproductive behaviours are preserved in Drosophila melanogaster infected with bacteria. Dryad Digital Repository. ( 10.5061/dryad.76hdr7szw) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Rose S. 2022. Pre-copulatory reproductive behaviours are preserved in Drosophila melanogaster infected with bacteria. FigShare. ( 10.6084/m9.figshare.c.5962396) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Data Availability Statement

The raw data and R code used for analysis has been deposited at Dryad: https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.76hdr7szw [54].

The data are provided in the electronic supplementary material [55].